CHAPTER 2

Sharing Code Among Platforms

Xamarin.Forms allows you to build apps that run on Android and iOS (and Windows 10 if working on Windows) from a single C# codebase. This is possible because, at its core, Xamarin.Forms allows the sharing among platforms of all the code for the user interface and all the code that is not platform-specific. There are different ways to share code among platforms, each with its pros and cons. This chapter explains the available code-sharing strategies in Xamarin.Forms, highlighting their characteristics so that it will be easier for you to decide which strategy is better for your solutions.

Introduction to code-sharing strategies

In Chapter 1, I explained how to create a Xamarin.Forms solution in Visual Studio for Mac. It is made up of three projects: two platform projects (Android and iOS), and a project that allows for sharing code among platforms. With this approach, developers can share all the code for the user interface and all the code that is not coupled to the APIs of each platform, maximizing code reuse and simplifying the process of creating three different native apps from a single C# codebase. In that explanation, I briefly introduced the Portable Class Library (PCL) as a project type that allows sharing code. However, Xamarin.Forms allows sharing code among platforms in three different ways: Portable Class Libraries, Shared Projects, and .NET Standard libraries. This chapter contains a thorough discussion of these three code-sharing strategies, providing further information about the PCL project type. It is worth mentioning that, at the time of writing, Visual Studio for Mac includes Xamarin project templates based on PCLs and Shared Projects, while you need some manual, yet easy steps for .NET Standard. In the section about .NET Standard, you will learn how to easily convert a PCL into a .NET Standard library.

Sharing code with Portable Class Libraries

As the name implies, Portable Class Libraries (PCL) are libraries that can be consumed on multiple platforms. More specifically, they can be consumed on multiple platforms only if they target a subset of APIs available on all those platforms. PCLs have existed for many years, and they are certainly not exclusive to Xamarin. In fact, they can be used in many other development scenarios. For example, a PCL could be used to share a Model-View-ViewModel architecture between different project types. The most important characteristics of a PCL are the following:

- They produce a compiled, reusable .dll assembly.

- They can reference other libraries and have dependencies, such as NuGet packages.

- They can contain XAML files for the user interface definition and C# files.

- They cannot expose code that leverages specific APIs of a certain platform; otherwise, they would no longer be portable.

- They are a better choice when you need to implement architectural patterns such as MVVM, factory, inversion of control (IoC) with dependency injection, and service locator.

- With regard to Xamarin.Forms, they can use the service locator pattern to implement an abstraction and to invoke platform-specific APIs through platform projects (this will be discussed in Chapter 8).

- They are easier to unit test.

For example, if you have a Windows development background, you can easily understand how a PCL that is used to share code between WPF and UWP projects could never contain code that accesses the location sensor of a device, because this is not supported in WPF and requires Windows 10 APIs that WPF cannot access. Instead, a PCL can be used to access Internet resources via the HttpClient class on multiple platforms, because this is commonly available. Normally, you would create a PCL project manually, and then add the necessary references to and from other projects in the solution. In the case of Xamarin.Forms, you instead decide a code-sharing strategy when creating a new project (see Figure 4), and then Visual Studio for Mac will automatically generate a PCL project that is referenced by the platform projects in the solution, and that has a dependency on the Xamarin.Forms NuGet package.

Note: In all the examples in this e-book, I will use the PCL as the code-sharing strategy for the following reasons: it makes it easier to use and manage other libraries, it is a better choice with real-world projects that require more complex architectures, and it is simpler to change into a .NET Standard library.

Sharing code with shared projects

Shared projects, as well as PCLs, are not specific to Xamarin and have existed for many years. Shared projects are essentially loose assortments of files that can be shared with other projects. The following is a list of the most important characteristics of a shared project, also highlighting the differences from a PCL:

- They do not produce a compiled, reusable .dll assembly.

- They cannot reference other libraries and have dependencies such as NuGet packages.

- They can contain XAML files for the user interface definition and C# files.

- They can contain platform-specific code that can use conditional compilation and preprocessor directives.

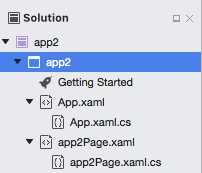

In order to select a shared project as the code-sharing strategy, in the New Project dialog (see Figure 4) you select Use Shared Library in the Shared Code group. When the solution is ready in the Solution pad, you will see the shared project looking similar to Figure 13.

Figure 13: The shared project in a Xamarin.Forms solution

One important note here is that platform projects (Android and iOS) have a reference to the shared project, but the shared project cannot have references or dependencies. Additionally, shared projects’ properties have no project-level properties; instead, you can only access the properties of the individual files they contain. Not surprisingly, there is no Properties or References node for shared projects in the Solution pad.

Shared projects can contain an almost unlimited number of different files and resources, including XAML files for the user interface and C# code files. This is possible because shared projects are not compiled; the compiler resolves source files and resources when the whole solution is built. The biggest benefit of shared projects is that they allow the writing of platform-specific code without needing to use patterns such as the service locator, as you do with PCLs. This is accomplished using preprocessor directives such as #if, #elif, #else, and conditional compilation symbols, as demonstrated in Code Listing 1.

Code Listing 1

private string GetFolderPath() { string path = "";

#if __ANDROID__ path = Environment.GetFolderPath(Environment.SpecialFolder.MyDocuments); #elif __IOS__ path = Environment.GetFolderPath(Environment.SpecialFolder.MyDocuments); #endif return path; } |

As you can see, you can simply check the platform your app is running on with preprocessor directives, and then the compiler will resolve the appropriate platform-specific code without dealing with the complexity of other patterns. Each platform is represented by a conditional compilation symbol, defined in the build options of the project properties. Table 1 summarizes the available symbols and the platforms they represent.

Table 1: Conditional compilation symbols in Xamarin.Forms

Symbol | Description |

|---|---|

__ANDROID__ | Represents the Android platform |

__IOS__ | Represents the iOS platform |

__TVOS__ | Represents the Apple tvOS platform |

__WATCHOS__ | Represents the Apple Watch OS platform |

NETCORE_FX | Represents the .NET Core platform |

An interesting example of platform-specific code that uses conditional compilation symbols and preprocessor directives is the SQLite.cs file, which implements data access against the popular SQLite database in C#. A complete sample solution based on shared projects and the approach described previously is available from the official Xamarin documentation, and is called Tasky. It shows how to create a simple To-Do mobile application. Having the option to write platform-specific code with the approach you saw in Code Listing 1 is certainly appealing, but you should prefer PCLs (and .NET Standard libraries) in at least the following situations:

- You need to access many platform-specific resources, and your code might become very difficult to maintain.

- You need to implement architectures based on one or more patterns. In such situations, not only are shared projects not the best option, but it is common to have multiple portable libraries, which also makes it easier for teams to work on different parts of a solution.

- You want to unit test your code efficiently.

The aforementioned points, together with the considerations I made in the section about portable libraries, should further clarify the reason you will find examples based on PCLs rather than shared projects in this e-book.

Sharing code with .NET Standard libraries

The .NET Standard provides a set of formal specifications for APIs that all the .NET development platforms, such as .NET Framework, .NET Core, and Mono, must implement. This allows for unifying .NET platforms and avoids future fragmentation. By creating a .NET Standard library, you will ensure your code will run on any .NET platform without the need to select any targets. This also solves a common problem with portable libraries, since every portable library can target a different set of platforms, which implies potential incompatibility between libraries and projects. Microsoft has an interesting blog post about .NET Standard and its goals and implementations, which will clarify any doubts about this specification.

At the time of writing, version 2.0 of .NET Standard is available, and it provides full unification for .NET Framework, .NET Core, and Mono. The documentation will help you choose the version of .NET Standard based on the minimum version of the platform your application is intended to run on. Xamarin.Forms has been supporting .NET Standard 2.0 since version 2.4.0, but at the moment, Visual Studio for Mac does not include .NET Standard as a code-sharing strategy when creating a new Xamarin.Forms solution. It is reasonable to expect that this code-sharing strategy will be included as a possible option in the future.

What you can do now is convert a Portable Class Library project into a .NET Standard library. To accomplish this, you need to follow these steps:

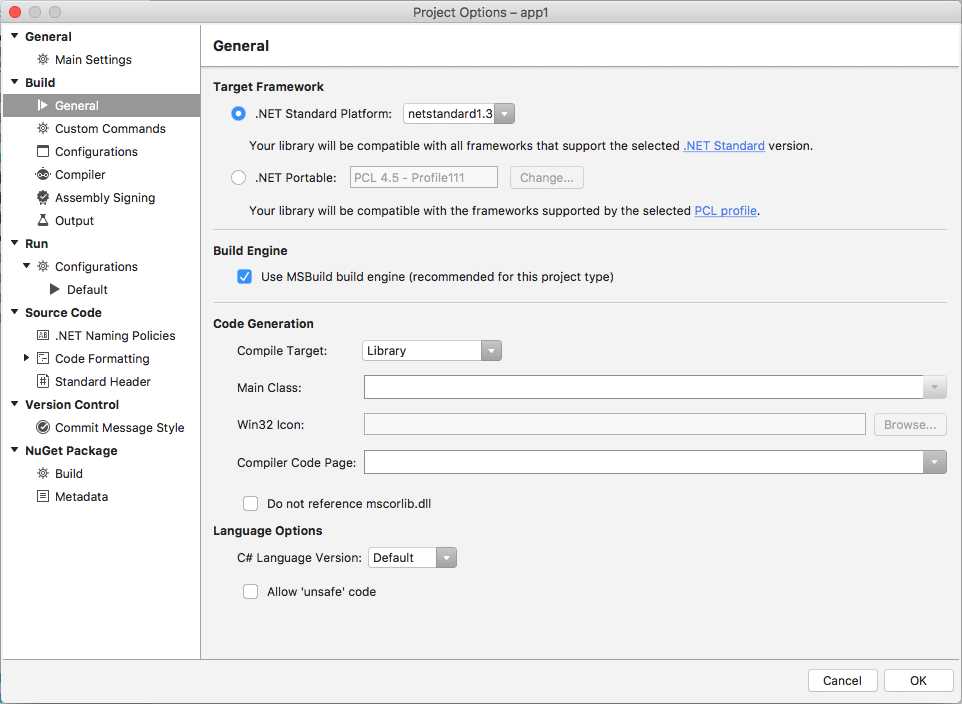

- In the Solution pad, right-click the PCL project name and select Options.

- When the Project Options dialog appears, click General under the Build node.

- In the Target Framework group (see Figure 14), select .NET Standard Platform, then select the version you wish to target. Notice that you can currently choose from version 1.0 to 1.5, and the choice I recommend is version 1.3. You can click the .NET Standard hyperlink for a comprehensive guide to framework compatibility in all the supported versions.

- Click the OK when ready.

Figure 14: Changing a PCL to a .NET Standard library

At this point, rebuild your solution. Now you have a .NET Standard library that can contain code that will almost certainly run on all the platforms that implement the specification.

Note: Even if .NET Standard is not yet included as a code-sharing strategy when creating a Xamarin.Forms solution, there is no doubt that this will be the code-sharing strategy of choice in the near future. For this reason, I recommend you have a look at the documentation and take some time to explore the API specifications.

Chapter summary

This chapter introduced the available code-sharing strategies that Xamarin.Forms can use to share user interface files and platform-independent code, such as Portable Class Libraries, shared projects, and .NET Standard libraries. PCLs produce reusable assemblies, allow for implementing better architectures, and cannot contain platform-specific code. Shared projects can contain platform-specific code with preprocessor directives and conditional compilation symbols, but they do not produce reusable assemblies, and code maintenance is more difficult if they access many native resources.

.NET Standard libraries represent the future of code sharing across platforms, are based on a formal set of API specifications, and they make sure your code will run on all the platforms that support the selected version of .NET Standard. Assuming that the Portable Class Library is the preferred choice, in the next chapters you will start writing code and building cross-platform user interfaces.

- 155+ high-performance Xamarin controls, including DataGrid, Charts, and ListView.

- Elegant XAML layouts for common scenarios.

- Layouts optimized for mobile and desktop.