CHAPTER 2

Inside WPF

What is XAML?

At the heart of WPF is a new XML-style declarative markup language called Extensible Application Markup Language, or XAML (pronounced “Zammel”). The nature of XAML allows the user interface to be completely independent from the logic in the code behind. As such, it’s incredibly easy to allow a graphics designer to work in a design tool such as Expression Blend while a developer works to complete the business logic in Visual Studio. XAML is a vast and powerful language. This separation of design and development is one of the driving reasons that Microsoft created XAML and WPF.

XAML allows the instantiation of .NET objects via declarative markup. You can import namespaces to dictate the elements available to your markup. For instance, you can create a class in C# that models a customer and declare the customer class as an application-level resource. Then you can access this resource via XAML from anywhere in your application.

In a classic WinForms application, you would design your user interface in Visual Studio and the IDE would emit C# or VB.NET in a partial class that represented the layout of your code. Each control, be it a button, text box, or otherwise, would have a corresponding line of code.

In WPF and XAML, you use the IDE of your choice to create XAML markup. This markup isn’t translated into code. It’s serialized into a set of tags that are loaded on the fly to generate the UI of your application.

Elements represent objects, and attributes represent the objects’ property values.

Here’s an example:

1 <Window x:Class="Chapter01.ControlsExample" 2 xmlns="http://schemas.microsoft.com/winfx/2006/xaml/presentation" 3 xmlns:x="http://schemas.microsoft.com/winfx/2006/xaml" 4 Title="ControlsExample" Height="300" Width="300"> 5 <Grid> 6 7 </Grid> 8 </Window> |

Elements as objects, attributes as properties

Line one is the definition of the Window object. Just like any other XML-based language, elements can be nested within other elements. The x:Class attribute specifies the name of the Window’s class. This is the class in which we will access the window programmatically from the code behind. Line two specifies the xmlns attribute, which represents a URI namespace. The URI looks like a web resource, though it’s not.

The http://schemas.microsoft.com/winfx/2006/xaml/presentation namespace URI defines all of the standard WPF controls. The xmlns is equivalent to the using statement in C#. Microsoft chose this naming scheme because by using a URI with the Microsoft domain, it’s unlikely that any other developer will use the same URIs when defining namespaces. There are roughly twelve different standard WPF assembly namespaces and all of them start with System.Windows. By specifying the URI, the code will search each of the namespaces and automatically resolve that the Window element maps to the System.Windows.Window class. It will find the Grid resides in the System.Windows.Controls assembly namespace.

Since line 2 imports the namespace in which all of the WPF elements reside, we do not add a suffix. Line 3 represents another default WPF namespace that contains many utility classes that dictate how your XAML document is interpreted. We apply the x suffix to this namespace. Then to access elements of this namespace, we will prefix the element with x:. For example, <x:MyElement>.

The following explanation of the xmlns attribute is reproduced from the XAML Overview (WPF) page provided on the Microsoft Developer Network documentation on WPF at https://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/library/ms752059(v=vs.110).aspx.

The xmlns attribute specifically indicates the default XAML namespace. Within the default XAML namespace, object elements in the markup can be specified without a prefix. For most WPF application scenarios, and for almost all of the examples given in the WPF sections of the SDK, the default XAML namespace is mapped to the WPF namespace http://schemas.microsoft.com/winfx/2006/xaml/presentation. The xmlns:x attribute indicates an additional XAML namespace, which maps the XAML language namespace http://schemas.microsoft.com/winfx/2006/xaml.

This usage of xmlns to define a scope for usage and mapping of a namespace is consistent with the XML 1.0 specification. XAML namespace is different from XML namespace only in that a XAML namespace also implies something about how the namespace's elements are backed by types when it comes to type resolution and parsing the XAML.

Note that the xmlns attributes are only strictly necessary on the root element of each XAML file. The xmlns definitions will apply to all descendant elements of the root element (this behavior is again consistent with the XML 1.0 specification for xmlns). The xmlns attributes are also permitted on other elements underneath the root, and would apply to any descendant elements of the defining element. However, frequent definition or redefinition of XAML namespaces can result in a XAML markup style that is difficult to read.

The WPF implementation of its XAML processor includes an infrastructure that has awareness of the WPF core assemblies. The WPF core assemblies are known to contain the types that support the WPF mappings to the default XAML namespace. This is enabled through configuration that is part of your project build file and the WPF build and project systems. Therefore, declaring the default XAML namespace as the default xmlns is all that is necessary to reference XAML elements that come from WPF assemblies.

XAML elements

In XAML, the objects that make up your UI are represented as elements. In the previous example, we had a root Window element that contained a grid control. The grid control is an object and is represented as an element. Please note that the grid is also a child element since it's contained within the opening and closing Window element tags. Also note that in some cases this parent/child relationship can be used to express object properties and values. Perhaps an example will help with this concept.

1 <Window x:Class="Chapter01.ControlsExample" 2 xmlns="http://schemas.microsoft.com/winfx/2006/xaml/presentation" 3 xmlns:x="http://schemas.microsoft.com/winfx/2006/xaml" 4 Title="ControlsExample" Height="300" Width="300"> 5 <Grid> 6 <Button Width="100" Height="50" Name="btnTestButton"> 7 Button Text 8 </Button> 9 </Grid> 10 </Window> |

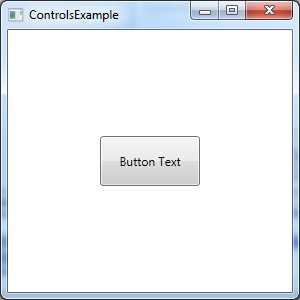

- Rendered Window, Grid, and Button Elements

Output

As we look at the elements, you'll notice that we have a window, a grid, and a button. The grid is a child element of the window and the button is a child of the grid. The button has a text value in between the opening and closing tags. This automatically sets the Content property of the Button object to Button Text. This is a prime example of how an element's child can represent an object or a property value much like an element attribute.

XAML attributes

As I've stated in the previous section, attributes represent object properties. Perhaps one of the most important element attributes is the name attribute. The name attribute provides access to the object from the code in the code behind. If your element doesn't have a name attribute set, you won’t be able to manipulate the object using C# or VB.NET code in the window code behind.

Due to the nature of XAML markup, all attribute values are specified as strings. There are many properties that must convert the string representation of an attribute value to a more complex data type. A perfect example of this is the Background property. The Background property will take a string name of a predefined set of colors and convert it to the proper SolidBrush object of the color upon compilation. This is achieved by a class called System.ComponentModel.TypeConverter.

- 100+ essential WPF UI controls like DataGrid, Charts, and Diagram.

- 10+ built-in themes, plus Theme Studio app for designing custom themes.

- Powerful document processing libraries for Excel, PDF, Word, and PowerPoint file formats.