CHAPTER 1

Introduction

Cloud Computing

If you have been developing software, managing infrastructure or even just watching television in the past several years, you have been inundated with references to cloud computing. You also may have been left scratching your head trying to figure out what it all means. It seems that every vendor has a slightly different definition for what cloud computing is and, appropriately, each vendor’s definition is tailored to the products and services that they offer. In simplest terms, cloud computing is just a compelling name to describe the concept of distributed computing over a network that has been a staple of application development for decades (much like when Google popularized the term “Ajax” in the early 2000s and people perceived a new paradigm).

Types of Cloud Computing

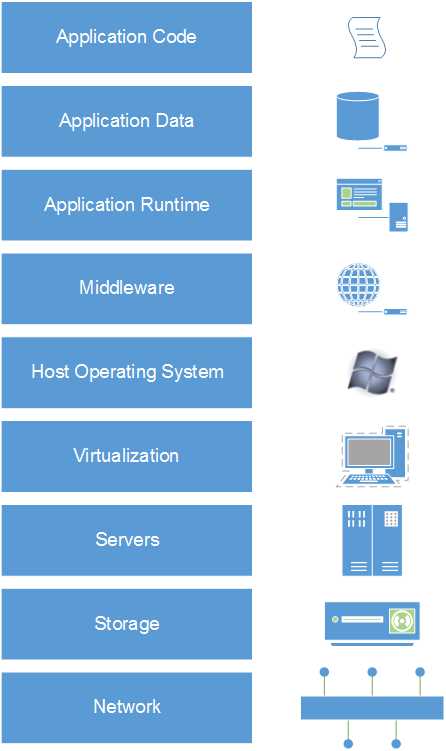

Most vendors do agree on a set of categories into which most cloud computing applications can be placed. The categories are based on the characteristics of the application, most commonly driven by the management tasks distributed among the host platform and customer. These categories (described in more detail later) include Infrastructure as a Service (IaaS), Platform as a Service (PaaS), and Software as a Service (SaaS). For the purposes of discussion, we’ll start with the assumption that a typical enterprise application has the following set of concerns at the infrastructure level (shown in Figure 1):

- Network: This includes the physical equipment such as switches and routers as well as the logical configuration of subnets. Many application developers often take the network part of the solution for granted, but there is no amount of code that can overcome the devastating effect of a poorly configured network on the stability and performance of an application.

- Storage: Most software applications and the businesses they support are highly dependent on the storage of data and in keeping that data safe from loss and unauthorized disclosure. Management tasks at the storage layer include configuring storage devices for optimum throughput, monitoring for device failure, tracking utilization, and ensuring that a backup plan exists and is followed.

- Servers: While my earliest memory of managing a network included wall-to-wall tower computers, each with a special function, the modern data center is characterized by fewer and larger physical machines, each hosting a number of virtualized servers. This model is much easier to manage than the model without virtualization, but it still brings a number of management tasks such as monitoring the servers for hardware failure, ensuring that adequate power is available for the equipment, and maintaining environmental conditions for optimal performance of the hardware.

- Virtualization: As noted in the discussion of physical servers, virtualization is the norm in the modern data center. Products such as Microsoft’s Hyper-V, VMware’s vSphere, and Citrix’s ZenServer all let you perform management tasks such as managing the distribution of physical resources among the virtual hosts, monitoring to optimize utilization of hardware, and provisioning and decommissioning of virtual hosts.

- Host Operating System: Virtualization does not remove the management tasks of host operating systems. These still need to be appropriately configured for performance, availability, and security. Management tasks often include ongoing application of operating system and security software (such as antivirus and intrusion detection) patches and any operating system-specific monitoring tasks that cannot be performed by the virtualization tool.

- Middleware: Middleware includes software that is used as a foundation on which to build applications without having to reinvent functionality commonly found within specific applications—allowing developers to focus on the specific value intended to be provided by their application. Common examples of middleware used by applications built on the Microsoft stack include (but certainly is not limited to) Microsoft Internet Information Services (IIS) (formerly Internet Information Server) to handle tasks such as managing request/response for HTTP requests, Microsoft AppFabric for providing a distributed cache, and Microsoft SQL Server to handle storage and retrieval of relational data. Each middleware comes with its own set of configuration and management tasks that varies by the complexity of the particular middleware, ranging from the “set it and forget it” nature of Microsoft AppFabric to the constant monitoring and tuning provided by database administrators for some Microsoft SQL Server implementations.

- Application Run Time: The application run time includes the container in which applications execute. For web applications built on the Microsoft stack, this container is most commonly Microsoft ASP.NET running either ASP.NET Web Forms or ASP.NET MVC. Certain run time configuration parameters (such as processing and memory resources to allocate to the container) are managed at the host level while other parameters are available for customization by the individual application.

- Application Data: The application data is usually the tangible product of having executed the application. Whether it’s recording bills of sale for a multinational product supplier or high scores in the latest bubble app craze, the management of what data to store and how to keep it consistent with the applicable rules is usually performed by the application code itself. Therefore, very little management activity that is not performed either at the storage or middleware layers is necessary.

- Application Code: The application code is the executable code that executes within the run time to perform actions directly related to achieving the goal of the application. This is typically the layer of the application stack most visible to the business stakeholders of the application. It is the layer on which the code most specific to solving problems related to the business domain can be found. I am often heard telling co-workers and clients that developers should work on solving problems that only they can solve. By that I mean developers should focus on the code in the application that is most focused on solving the specific business problem, instead of trying to reinvent frameworks for solving problems that are already addressed in common frameworks or by the run time.

- Full application stack

On-Premises Solution

On-premises solution is a term used to describe the traditional data center where all of the infrastructure and equipment is managed by the owner of the application. It is not a cloud computing model but is included in this discussion to establish a baseline for when cloud computing is not being used. It is also included because some scenarios will include resources that are not hosted in a cloud environment. In this model, all aspects displayed in Figure 1 are under the control and the responsibility of the application owner. When managed well, this often results in having to keep several departments’ worth of specialized staff to operate the pieces of the application as well as significant ongoing capital expenditure.

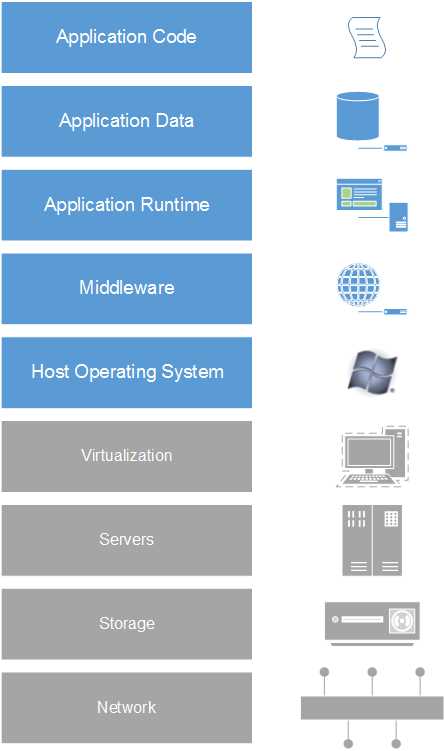

Infrastructure as a Service

The Infrastructure as a Service (IaaS) model takes everything below the host operating system on the application stack as the responsibility of the host or host platform, leaving the host operating system and everything above it on the stack as the responsibility of the application owner. This arrangement (shown in Figure 2) allows for fine-grained control of the operating characteristics of the application and its host operating system. It is often seen as the first step that a company takes towards achieving a virtual data center because virtualized servers running the application can often be transferred to the hosted environment with no code changes to the application itself (and with only the configuration changes necessary to reflect that the application has a new home).

Organizations that move from an on-premises model to IaaS typically find cost savings in the form of reduced utility costs from no longer needing to power and cool servers, reduced capital equipment costs from no longer needing to purchase big servers, and reduced personnel expenses from no longer needing staff to perform the physical portions of managing server hardware in the data center.

While significant savings can be achieved with IaaS, organizations maintain the ability and responsibility to control the configuration and management of pieces of the stack that are not directly related to the application code or its data—namely, the host operating system, middleware, and application run time. This can be beneficial in some cases because of the additional control it gives to the owner of the application. But it also requires attention and specialized skills, which makes the IaaS option most appropriate when there is something special about the needs of an application that makes it unsuitable to give up control over these pieces of the stack.

- IaaS stack

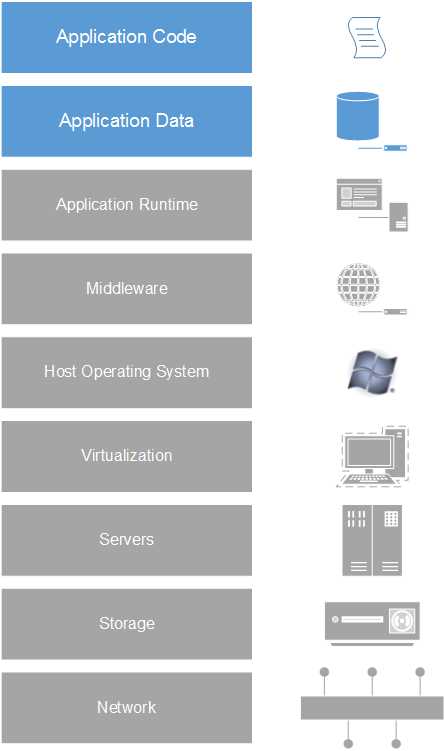

Platform as a Service

The Platform as a Service (PaaS) model further reduces the pieces of the application stack that must be managed by the application owner to only the application data and application code itself as shown in Figure 3. In this model, the application owner writes code that is designed to run within an application run time that is hosted by the service provider—sometimes limited to a specific set of application programming interface (API) functionality. This model requires far less specific knowledge and skill in the operation and management of network and infrastructure, but leaves some application owners with the uneasy feeling of having critical business assets outside of their reach or control. The mitigation for this uneasiness is often a combination of growing accustomed to the model and finding a partner that can be trusted to keep these assets protected—whether that protection comes from their ability to keep things safe or from a contractual commitment to provide adequate relief if a compromise occurs.

- PaaS stack

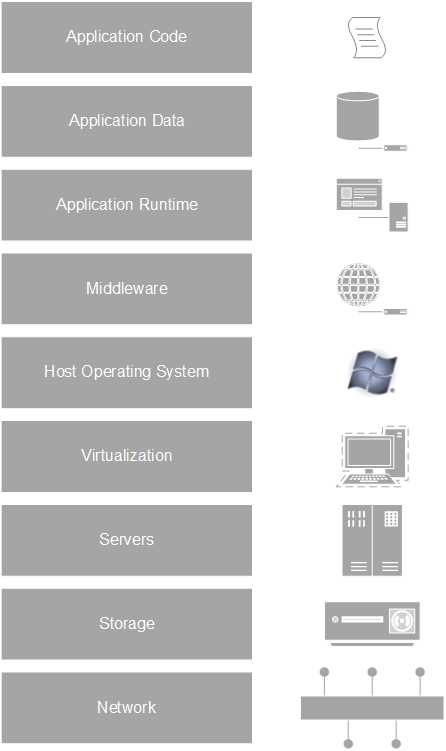

Software as a Service

The Software as a Service (SaaS) cloud computing model takes all of the configuration and management responsibilities away from the application owner (as illustrated in Figure 4) and allows the application to simply be used as is (although sometimes with limited customization through configuration) to meet specific goals. This model is often seen used with general-purpose software such as email, word processing, and collaboration tools as well as with certain specific-use offerings that have use across industries. Some examples of SaaS offerings include Microsoft’s Outlook.com and Office365 as well as out-of-the-box Salesforce.com (Salesforce also has a PaaS offering that allows you to build your own custom applications).

- SaaS stack

Hybrid

While we have looked at on-premises, IaaS, PaaS, and SaaS as distinct models with clearly defined responsibilities (marking the difference between which model an organization is participating in), the reality is most organizations have either settled on an approach that is some combination of these models or are in a transitory state—moving to a desired future state that is one model but still retaining some portion of their previous model. These organizations will either temporarily or permanently use a hybrid model that is some combination of two or more of these models. One example of a hybrid model would be a customer application built on the IaaS or PaaS model, connecting to an on-premises mainframe application that is critical to the organization’s business goals but cannot be migrated to a hosted environment.

What This Book is About

In this book we will be looking at the suite of products and services designed to enable cloud computing that Microsoft collectively markets under the Windows Azure brand. Our main focus will be on a specific product of that suite called Windows Azure Web Sites which provides the facilities to quickly and simply host data-driven websites that are suitable for many people’s needs—without additional services and complexity. We will also, at times, look beyond the out-of-the-box features of Windows Azure Web Sites at the other capabilities of Windows Azure products to meet more advanced needs that aren’t covered by the Windows Azure Web Site product.

Note: Windows Azure implements a pay-as-you-go model, so care will be taken in this book to call out when features that incur additional costs are being described. With any cloud-based product, you should make sure that you fully understand the costs of the features that you are using.

- 1800+ high-performance UI components.

- Includes popular controls such as Grid, Chart, Scheduler, and more.

- 24x5 unlimited support by developers.