CHAPTER 5

Routing

The source code presented in this section is in the folder Examples\Chapter 5 in the Bitbucket repository. The Visual Studio solution file is in the Chapter 5\Clifton.WebServer folder.

Now it’s time to talk about routing. The previous examples are still for a static web server—we have no way of hooking into page requests, and equally important, doing different things based on the verb used in the request, which is vital for supporting AJAX and REST APIs.

Routing is also somewhat entangled with session state:

- Is the user authorized to view the page?

- Has the session expired?

- Does the user’s role give the user access to the page?

For example, in Ruby on Rails, authorization is often accomplished in the superclass of the controller whose methods are being invoked through a routing table. In ASP.NET MVC, whether the user must be authorized is determined by the authorize attribute decorating the controller method. Again, the controller method is being invoked via a routing table. Role can also come into play as well as other factors, such as whether the session has expired or not.

Having worked with the previous two approaches, as well as implementing specialized base class controllers such as ExpirableController and AuthorizedRoleExpirableController, the approach that I prefer decouples routing from session and authorization/role state and takes a more “functional programming” approach rather than an object-oriented or attribute-decoration approach.

This approach also works well with the workflow paradigm presented earlier, and therefore has a nice consistent feel to it. But without discussing the pros and cons of each approach, you should be getting a sense that there are places in a web server’s design that are really up to the designer and where you, as the “user” of the web server architecture, get very little say in those design decisions.

Happily, the workflow paradigm actually does give you considerable more say because you can actually implement your own routing and session state management. What’s provided here is an example, but if you wanted to use a more object-oriented approach or reflection to check the authorization requirement on a controller, you could certainly implement that.

However, the reason routing is entangled with authorization and session management is that, well, it makes sense. There are pages that are publicly accessible, or privately accessible with the right role. Most, if not all, private pages can be expired.

So from a declarative perspective, it makes sense to define the constraints of a page (or a REST API endpoint) along with its route. What I’m proposing here as an implementation is to declaratively describe the routes and their constraints and implement the process of constraint checking and routing separately, as opposed to an entangled implementation.

A Routing Entry

For the reasons stated previously, a route entry will consist of three “providers”:

- SessionExpirationProvider

- AuthorizationProvider

- RoutingProvider

These providers are associated with whatever page or REST API path you want. For example:

public class RouteEntry { public Func<WorkflowContinuation<HttpListenerContext>, public Func<WorkflowContinuation<HttpListenerContext>, public Func<WorkflowContinuation<HttpListenerContext>, } |

Code Listing 42

Note that the provider functions have the signature of a workflow process.

We’ll cover Session in the next chapter.

A Route Key

We also need a route “key,” which is the lookup key for the route dictionary—the verb and path:

/// <summary> /// A structure consisting of the verb and path, suitable as a key for the route table entry. /// Key verbs are always converted to uppercase, paths are always converted to lowercase. /// </summary> public struct RouteKey { private string verb; private string path; public string Verb { get { return verb; } set { verb = value.ToUpper(); } } public string Path { get { return path; } set { path = value.ToLower(); } } public override string ToString() { return Verb + " : " + Path; } } |

Code Listing 43

A Route Table

A route table maps the routing key (the verb and path) with a route entry. To ensure thread safety, we use .NET’s ConcurrentDictionary, even though technically, the route table should not be modified after initialization. However, we don’t want to constrain the web server application to this—who knows, you may have a very good reason to modify the routing table via a route handler!

public class RouteTable { protected ConcurrentDictionary<RouteKey, RouteEntry> routes; public RouteTable() { routes = new ConcurrentDictionary<RouteKey, RouteEntry>(); } /// <summary> /// True if the routing table contains the verb-path key. /// </summary> public bool ContainsKey(RouteKey key) { return routes.ContainsKey(key); } /// <summary> /// True if the routing table contains the verb-path key. /// </summary> public bool Contains(string verb, string path) { return ContainsKey(NewKey(verb, path)); } /// <summary> /// Add a unique route. /// </summary> public void AddRoute(RouteKey key, RouteEntry route) { routes.ThrowIfKeyExists(key, "The route key " + key.ToString() + } /// <summary> /// Adds a unique route. /// </summary> public void AddRoute(string verb, string path, RouteEntry route) { AddRoute(NewKey(verb, path), route); } /// <summary> /// Get the route entry for the verb and path. /// </summary> public RouteEntry GetRouteEntry(RouteKey key) { return routes.ThrowIfKeyDoesNotExist(key, "The route key " + key.ToString() + } /// <summary> /// Get the route entry for the verb and path. /// </summary> public RouteEntry GetRouteEntry(string verb, string path) { return GetRouteEntry(NewKey(verb, path)); } /// <summary> /// Returns true and populates the out entry parameter if the key exists. /// </summary> public bool TryGetRouteEntry(RouteKey key, out RouteEntry entry) { return routes.TryGetValue(key, out entry); } /// <summary> /// Returns true and populates the out entry parameter if the key exists. /// </summary> public bool TryGetRouteEntry(string verb, string path, out RouteEntry entry) { return routes.TryGetValue(NewKey(verb, path), out entry); } /// <summary> /// Create a RouteKey given the verb and path. /// </summary> public RouteKey NewKey(string verb, string path) { return new RouteKey() { Verb = verb, Path = path }; } } |

Code Listing 44

The Route Handler

The route handler vectors the request to the supplied handler, if one exists:

/// <summary> /// Route requests to an application-defined handler. /// </summary> public class RouteHandler { protected RouteTable routeTable; public RouteHandler(RouteTable routeTable, SessionManager sessionManager) { this.routeTable = routeTable; } /// <summary> /// Route the request. If no route exists, the workflow continues, otherwise, /// </summary> public WorkflowState Route(WorkflowContinuation<HttpListenerContext> { WorkflowState ret = WorkflowState.Continue; RouteEntry entry = null; if (routeTable.TryGetRouteEntry(context.Verb(), context.Path(), out entry)) { ret = entry.RoutingProvider(workflowContinuation, context, session); } return ret; } } |

Code Listing 45

Remember, we’ll look at sessions and session management in the next chapter, so for now we can ignore the session management property.

Try It Out

We can test this very simply, by writing a handler for a page we want to fault on:

public static void InitializeRouteHandler() { routeTable = new RouteTable(); routeTable.AddRoute("get", "restricted", new RouteEntry() routeHandler = new RouteHandler(routeTable); } |

Code Listing 46

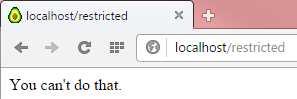

Here we’re leveraging the previously implemented exception handler to display the message in the browser window. When we request this page (via get), we’ll get the message “You can’t do that.”

We add the routing handler to our workflow:

public static void InitializeWorkflow(string websitePath) { StaticContentLoader sph = new StaticContentLoader(websitePath); workflow = new Workflow<HttpListenerContext>(AbortHandler, OnException); workflow.AddItem(new WorkflowItem<HttpListenerContext>(LogIPAddress)); workflow.AddItem(new WorkflowItem<HttpListenerContext>(WhiteList)); workflow.AddItem(new WorkflowItem<HttpListenerContext>(requestHandler.Process)); workflow.AddItem(new WorkflowItem<HttpListenerContext>(routeHandler.Route)); workflow.AddItem(new WorkflowItem<HttpListenerContext>(sph.GetContent)); } |

Code Listing 47

And voilà!

Figure 8: Routing Example

Qualifying Routes by Content Type

It may also be useful to qualify a route handler by the content type. Let’s say you have a route where you need to handle both application/json (say, from an AJAX call) and application/x-www-form-urlencoded (say, from a form post). It could be useful to qualify the route by the content type in addition to the verb and path. As it turns out, some web servers don’t actually support that ability, but as we see in Chapter 10, “Form Parameters and AJAX,” content type can be a useful qualifier.

IMPORTANT: Because not all web servers support qualifying routes by content type, you may discover that your web application all of a sudden breaks! Use this feature with care. Marc LaFleur wrote an excellent article on adding content type routing to ASP.NET Web API.

Conclusion

Routing is great example of the different ways one can write the handlers—you can use anonymous methods, as I did previously, an instance method, or a static method. You can add extension methods or just define methods that promote session and authentication check re-use, which we’ll explain in the next chapter on sessions. Also, you should be getting a sense of the repeatability of the workflow pattern. We will take advantage of the same pattern for session and authorization in the next chapter.

- 1800+ high-performance UI components.

- Includes popular controls such as Grid, Chart, Scheduler, and more.

- 24x5 unlimited support by developers.