CHAPTER 9

Parameterized Routes

The source code presented in this section is in the folder Examples\Chapter 9 in the Bitbucket repository. The Visual Studio solution file is in the Chapter 9\Clifton.WebServer folder.

A common practice is to add parameters within a route. You’ll see this used frequently in Ruby on Rails applications, though I much prefer putting the parameters in the parameter section of a URL. Regardless, there’s no reason to make a “Marc Clifton” opinionated server, so we should support this feature.

What is a parameterized route? It could look like this:

localhost/items/1/subitems

where 1 is the ID of an item in the items collection.

Or, another example:

localhost/items/groceries/subitems

where groceries is the name of an item in the items collection. There are a variety of assumptions that a router will make with regards to the second form to replace “groceries” with the ID value. Here are some of the possible assumptions:

- There’s a table called “Items”.

- There’s a model called “Item” in the singular.

- The model may (or may not) define a way to map a non-numeric parameter to a lookup field.

- The router has the ability to look up an ID from a non-numeric parameter, either directly from the database, or indirectly through a model.

The issue can be considerably more complex. Consider the routing options that NancyFx supports:

- Literal segments (like mypage/mystuff/foobar).

- Capture segments (what I’m calling parameterized URLs) like /tasks/{tasked}.

- Optional capture segments.

- Capture segments with default values.

- RegEx segments.

- Greedy segments.

- Greedy RegEx segments.

- Multiple Captures Segment.

These are all potentially useful ways of pattern-matching a URL on a route handler. This should give you a sense of the complexities one could introduce into routing. For the purposes of this chapter, we’ll keep it fairly simple and focus on simply capturing the parameter and passing it into the route handler in the PathParams collection. But it does suggest that there be a way to call back to the application for very specialized routing requirements.

Agreeing on a Syntax

We can use whatever syntax we want for how parameters in the path are specified. For example, we might require a form like this (used by Rails):

param/:p1/subpage/:p2 |

Code Listing 68

However, we’ll use the ASP.NET MVC and NancyFx form:

param/{p1}/subpage/{p2} |

Code Listing 69

Handling IDs

Recall in our RouteHandler that we make a call in an attempt to acquire the route handler:

if (routeTable.TryGetRouteEntry(context.Verb(), context.Path(), out entry)) |

Code Listing 70

It’s currently implemented as a few overloaded methods of these two names:

public RouteEntry GetRouteEntry(RouteKey key) { return routes.ThrowIfKeyDoesNotExist(key, "The route key " + key.ToString() + " does not exist.")[key]; } { return routes.TryGetValue(NewKey(verb, path), out entry); } |

Code Listing 71

Here we expect an exact match between the request path and the route’s definition. We need to refactor this code (and some other areas of the code which I will not show because they’re trivial) to match on a parameterized URL, and we would like those parameters returned in a key-value dictionary, for which I’ve simply derived a specific type:

public class PathParams : Dictionary<string, string> { } |

Code Listing 72

We refactor the GetRouteEntry methods to a form similar to this (not all overloads are shown):

public RouteEntry GetRouteEntry(RouteKey key, out PathParams parms) { parms = new PathParams(); RouteEntry entry = Parse(key, parms); if (entry == null) { throw new ApplicationException(“The route key “ + key.ToString() + “ does not exist.”); } return entry; } |

Code Listing 73

We implement a simple parser that iterates through the routes, and finds the first one that matches. This method has two parts: the iterator and the matcher. First, the iterator:

/// <summary> /// Parse the browser's path request and match it against the routes. /// If found, return the route entry (otherwise null). /// Also if found, the parms will be populated with any segment parameters. /// </summary> protected RouteEntry Parse(RouteKey key, PathParams parms) { RouteEntry entry = null; string[] pathSegments = key.Path.Split('/'); foreach (KeyValuePair<RouteKey, RouteEntry> route in routes) { // Above all else, verbs must match. if (route.Key.Verb == key.Verb) { string[] routeSegments = route.Key.Path.Split('/'); // Then, segments must match. if (Match(pathSegments, routeSegments, parms)) { entry = route.Value; break; } } } return entry; } |

Code Listing 74

Followed by the matcher (note how we could add additional behaviors here for matching a capture segment should we wish to):

/// <summary> /// Return true if the path and the route segments match. Any parameters in the path /// get put into parms. The first route that matches will win. /// </summary> protected bool Match(string[] pathSegments, string[] routeSegments, PathParams parms) { // Basic check: # of segments must be the same. bool ret = pathSegments.Length == routeSegments.Length; if (ret) { int n = 0; // Check each segment. while (n < pathSegments.Length && ret) { string pathSegment = pathSegments[n]; string routeSegment = routeSegments[n]; ++n; // Is it a parameterized segment (also known as a "capture segment")? if (routeSegment.BeginsWith("{")) { string parmName = routeSegment.Between('{', '}'); string value = pathSegment; parms[parmName] = value; } else // We could perform other checks, such as regex. { ret = pathSegment == routeSegment; } } } return ret; } |

Code Listing 75

Test It Out!

Let’s write a route handler that expects two parameters and gives us our parameter values back in the browser. The implementation looks like this (note, the RouteHandler was also refactored to add a PathParams parameter):

routeTable.AddRoute(“get”, “param/{p1}/subpage/{p2}”, new RouteEntry() { RouteHandler = (continuation, context, session, parms) => { context.RespondWith(“<p>p1 = “ +

return WorkflowState.Done; } }); |

Code Listing 76

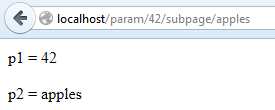

Now, when we visit that page and substitute some parameters directly into the URL, we see the server echoing back our captured parameters:

Figure 31: Path Parameters

Notice how we don’t care about the parameter type: it can be an integer, a float, or a string, as long as it contains valid characters for the path portion of the URL.

Conclusion

While relatively easy to implement, parameterized routes add complexity to resolving routes and therefore degrade the performance of the application, especially if you have hundreds of routes and thousands of simultaneous requests. This is why, at the beginning of this chapter, I stated that I do not prefer parameterized URLs.

While it’s useful to support parameterized routes, we should still support the more optimized lookup implemented earlier. This is accomplished by first checking against the route table with a path “as is.” The implementation of this is not shown here, but is in the source code repo for this book.

- 1800+ high-performance UI components.

- Includes popular controls such as Grid, Chart, Scheduler, and more.

- 24x5 unlimited support by developers.