CHAPTER 1

Introduction

In the past, the association between Microsoft and Windows was automatic. Windows is, without any doubt, the most famous product (together with Office) created by the software house from Redmond. And today, despite all the changes in the computing world, Windows is still the most widely adopted operating system in the world, both by consumers and enterprises.

Today, Microsoft doesn’t mean just Windows anymore. The new digital transformation has deeply changed the Microsoft mission. The original goal of the company was to bring a computer to every house and every office, but the world has changed. Computers aren’t just used for technical and business purposes anymore. Additionally, new kinds of computing experiences have emerged, like mobile phones and virtual reality. Consequently, the Microsoft mission, under the leadership of the new CEO Satya Nadella, has changed to embrace the quick transformation happening in the digital world: empower all people and every company in the world to achieve more. This goal can’t be achieved with just traditional computers. Mobile, cloud, Internet of Things, and business intelligence are just a few of the technologies opening new and exciting scenarios every day. As a result, in recent years Microsoft has started to embrace a deep change by embracing a new and bold approach. They pushed the cloud, turning Azure into one of the most productive cloud platforms in the world; they started to work with the open-source world by collaborating with communities to improve development tools and frameworks; they started to release their products and services on competitive platforms, like Android, iOS, and OS X, because Microsoft wants to help people be productive no matter which is their platform of choice.

Despite these changes, Windows remains one of the key products of the company and the best environment to empower people and companies to achieve their goals, no matter if we’re talking about playing the latest triple A game or writing a document in collaboration with a work team.

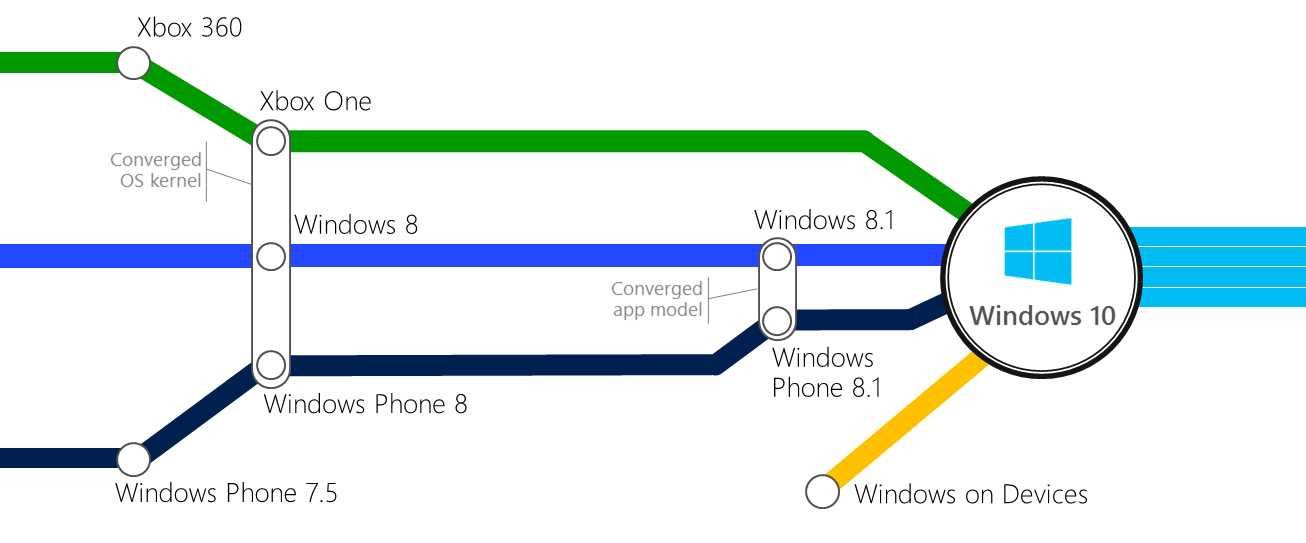

Windows 10 is the current generation of Windows and it’s simultaneously an end and a starting point of a journey. It’s the end of a convergence path with the goal of unifying all efforts to create a modern operating system running on modern devices; it’s the start of a new concept of operating system, more agile and able to adapt more quickly to the continuous changes that are happening in the digital world.

This book is dedicated to developers and to the Universal Windows Platform, the new development platform that can be leveraged to create modern and powerful applications, capable of running not just on traditional desktops, but on all kinds of modern devices, from the most traditional ones (like mobile phones or tablets) to the most innovative technologies, like 2-in-1s, the Internet of Things, or virtual reality.

The convergence journey

Windows has always been a very conservative ecosystem with a strong focus on productivity and long-term commitment and support, rather than being known for its innovative user experience or its disruptive features.

However, with the release of Windows Phone 7 in 2010, something changed. For the first time, Microsoft took the bold approach by releasing a platform with a completely new user experience and a new UI language, both from consumer and developer points of view. It was something new in the mobile world that offered a completely different experience from its predecessor, Windows Mobile.

The change introduced in Windows Phone slowly started to spread across all the other products of the Microsoft family. At first, the focus was on the unification of the user experience: distinctive features like tiles and a Store to look for apps and games in started to appear on other Microsoft platforms, like Xbox and Windows, with the release of Windows 8.

At the same time, Microsoft also started a convergence journey from a technical point of view. The goal was to create more synergy among teams that were working on a similar product (an operating system) that, in the end, they were just running on different devices.

Windows 8 was the first step of this convergence, sharing the same kernel that was used for the Xbox One and Windows Phone 8. For the end user or the developer, this change didn’t have such a big impact. However, under the hood, it had a huge impact for OEMs and the engineering teams, because one kernel means that the same set of drivers can be used across multiple devices, reducing the effort required to support all the different Windows platforms.

Meanwhile, Windows 8 also introduced a development platform called Windows Runtime (WinRT), which leveraged a completely different approach from the traditional .NET framework. Instead of a managed environment that can be installed on multiple Windows versions, the Windows Runtime is a native layer of APIs that can talk directly with the Windows kernel. We’re going to get into more detail when we talk about the Universal Windows Platform. Windows Runtime introduced a lot of benefits for apps developers. It’s faster than a managed environment, and it offers a broader set of APIs to solve many of the challenges developers experience in the modern world, like cloud access, integration with sensors and Bluetooth devices, optimization for battery power and performance, etc. However, the original version of the Windows Runtime had a downside: it was supported only by Windows 8. Consequently, despite Windows 8 and Windows Phone 8 sharing many of the same features, they were implemented in a different way. Windows 8 was based on the Windows Runtime, while Windows Phone 8 was still based on Silverlight and the traditional .NET Framework. Therefore, the convergence was more theoretical than practical. To support both platforms, a developer was still required to write two completely different applications.

The new update of both operating systems (Windows 8.1 and Windows Phone 8.1) took the journey to the next step and, finally, the end users and developers started to gain some benefits from this convergence. Windows 8.1 expanded the Windows Runtime by adding many missing features required by developers. Additionally, the improved version of Windows Runtime appeared for the first time on the mobile platform with Windows Phone 8.1. There were still some differences to handle (due to the different natures of phones and desktops or tablets), but most of the codebase could be shared between the two platforms, making it much easier for developers to target both platforms with the same application.

This change introduced benefits for the end users, too. Switching between Windows and Windows Phone was a breeze, thanks to a common user experience and a common set of apps. Windows Runtime’s new features (like the concept of roaming storage) made it easier for developers to keep data and information in sync across the platforms.

However, the convergence wasn’t complete yet. Thanks to the concept of shared projects (which allow users to easily share code among multiple projects) it was easy to share code but, in the end, developers still had to deal with two different platforms, which meant handling two different projects in Visual Studio, two different build packages, two different Stores in which to publish their apps, and doubling their efforts in order to reach both platforms.

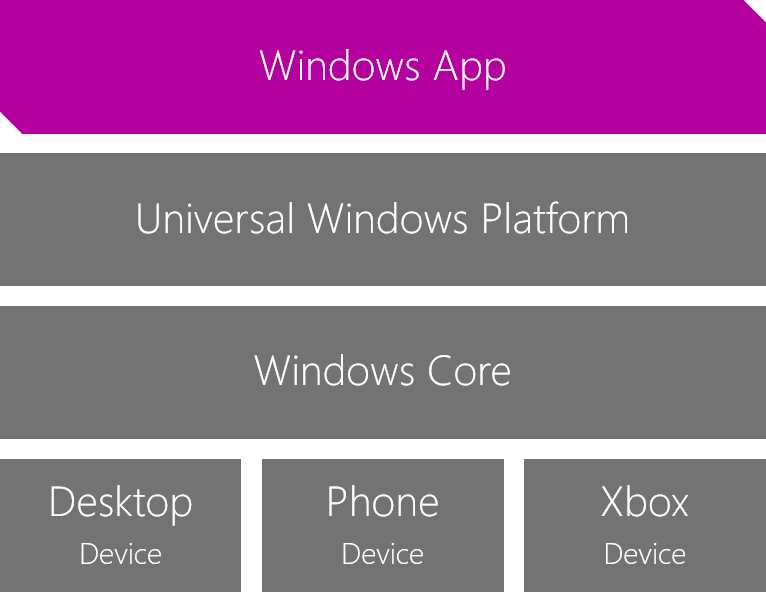

Figure 1: The platform convergence journey.

Windows 10: The end of a journey

Windows 10 was the last step in the convergence journey and, finally, it brings all the pieces to the right place. With Windows 10, Microsoft achieves the goal of having a common operating system, a common kernel, and a common development experience across multiple platforms by removing all the idiosyncrasies that made developers’ lives more complicated in the past.

Windows 10 is a single operating system capable of running on multiple devices. No matter if it’s a phone, tablet, traditional desktop, or gaming console, they all share the same core, the same kernel, and the same set of APIs, thanks to an evolution of the Windows Runtime called Universal Windows Platform. The only difference among the devices is in the shell, which is the interface leveraged by the user to interact with the device. A traditional desktop offers a shell optimized for mouse and keyboard; a phone or tablet has a shell optimized for touch interaction; an Xbox One has a shell optimized for game controllers.

The app experience has also been unified. As a developer, you won’t have to deal anymore with multiple projects, one for each platform. Instead, you’ll have a single project capable of running on any device and, thanks to the new features added to the development platform (like adaptive triggers and capabilities detection, which we’re going to explore in the other chapters), the application can be easily optimized for the various shells by handling key factors like screen size or input control. This unification is also reflected in the Store. The discovery and download experience is now the same across every platform, which means that an app bought on a phone will be automatically also available on the PC or console since, under the hood, the user will be downloading the same app.

Last but not the least, Windows 10 has also expanded the Microsoft ecosystem by supporting new and innovative devices:

IoT Core is a Windows 10 version dedicated to makers who want to leverage the power of the Universal Windows Platform and the Windows Core to create new experiences in the Internet of Things world, a trending topic nowadays. Windows 10 IoT Core can run on microcomputers and boards like the Raspberry PI, which are very popular among makers and manufacturers to connect traditional objects to the Internet in order to collect and analyze data.

Surface Hub is a device dedicated especially to business and enterprises that can easily become a game changer in conference rooms and collaborative scenarios. It’s a computer with a huge touch screen (either a 55’’ or 84’’ screen) and a 100point multitouch sensor. It comes with a Windows 10 shell capable of running UWP apps and with a set of built-in productivity tools that are optimized to empower collaboration scenarios (like conference calls, shared draw boards, etc.).

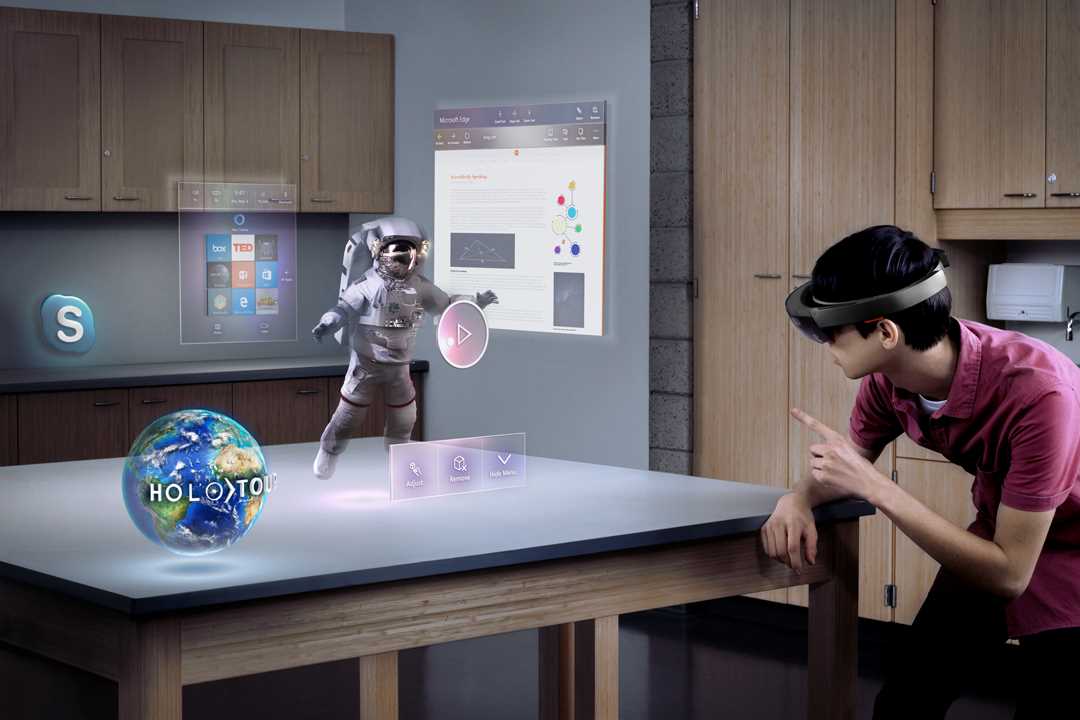

HoloLens is the outcome of eight years of research and development in virtual reality and augmented reality, the first of its kind in a new category called mixed reality. It’s a special set of glasses capable of running without a connection to a PC or to a phone. They can project holograms over the existing environment, opening up a wide range of new scenarios and possibilities in the consumer and enterprise worlds. HoloLens is capable of running applications based on the Universal Windows Platform. In this case, developers will be able to leverage a specific set of APIs to create a new kind of experience by detecting, for example, the movement of the user’s eye or hand gestures. If you want to know more, I suggest you visit the official YouTube channel of the HoloLens team.

Figure 2: The mixed reality experience made possible by HoloLens.

Windows 10: The beginning of a new journey

Windows 10 is also the beginning of a new journey, since it introduces a completely new lifecycle model. In the past, Microsoft has typically released a new version of the operating system every 3-4 years, with a series of service packs in between. These were mainly collections of patches and security fixes to make the computer more secure and to support new technologies that may have been released (like USB 3.0).

This approach doesn’t fit anymore into the current digital world, where things change at a much faster pace. Every year we see new trends and new disruptive technologies, so 3-4 years is too long a time frame to stay up-to-date with all these changes.

As such, Windows 10 has introduced a new model called Windows as a service, which led many tech journalists to define it as “the last version of Windows.” Technically, this definition is true, but not because Microsoft is going to quit the operating system business after the release of Windows 10, but because Windows 10 will be continuously evolving by adding new features over time.

The update frequency will be higher than the traditional service pack approach (approximately, Microsoft is going to release two updates per year) and each update won’t bring just the usual patches and security updates (which will continue to be delivered regularly when needed), but also new features for users and new APIs for developers.

Each major update corresponds to a specific build number and to a specific SDK release. Let’s see the versions released so far.

Windows 10 (build 10240)

The original version of Windows 10 was fully released to the public on July 29, 2015, and was identified by the build number 10240. This version was dedicated to traditional desktop and tablet devices: at the time of release, the mobile version of Windows 10 wasn’t ready yet.

The goal of this first release was to make Windows 8 a more modern operating system, optimized also for touch devices, while still keeping the familiar Windows experience users had appreciated since Windows XP.

Here are some of the most important added or improved features.

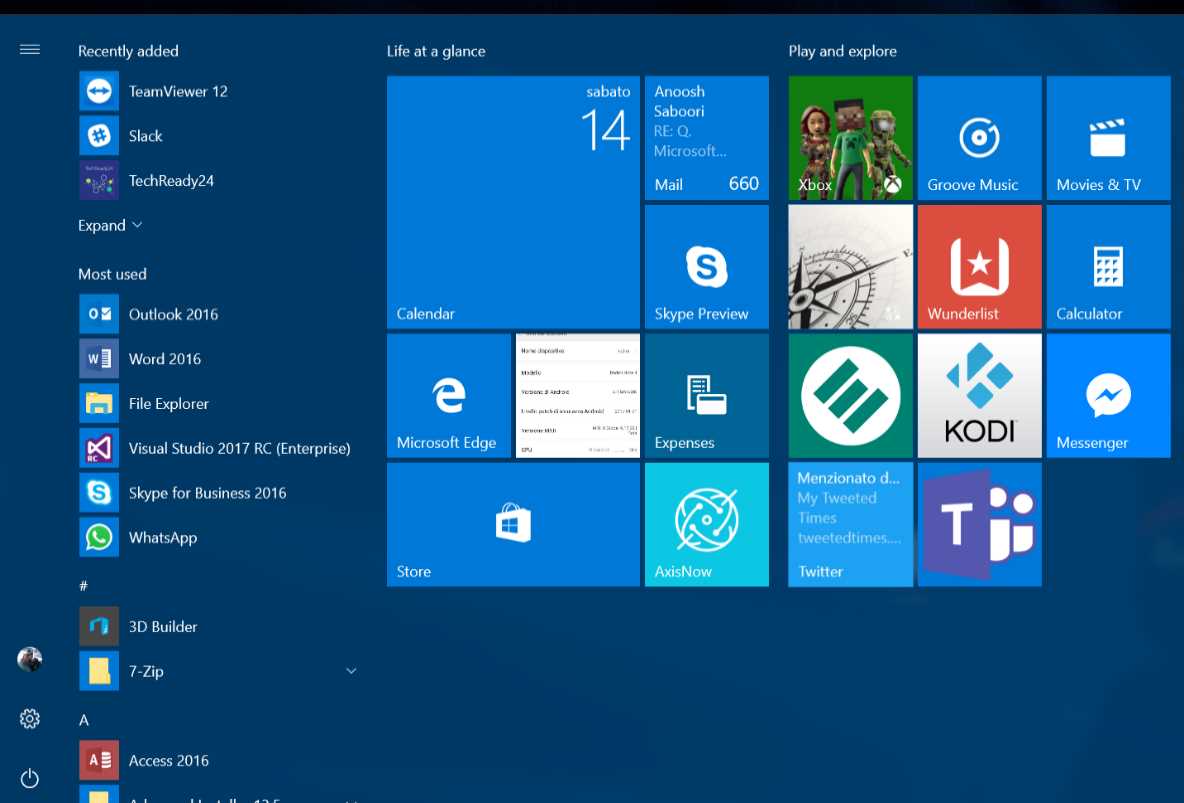

The Start menu

Windows 8 introduced a completely revamped Start menu, inspired by the Windows Phone start screen and greatly optimized for touch devices, offering a full screen experience, live tiles, and much more.

However, many Windows users found it challenging to use, since it was a completely different approach than the one offered by its predecessors. Additionally, the full screen experience was forcing the user to continuously shift the focus from the task they were doing on the desktop to the Start menu whenever they needed to open a new app or perform another task.

Windows 10 introduced a new Start Menu offering the best of both worlds: a familiar visual experience, which takes just a small portion of the screen and displays an alphabetical list of all the applications installed on the computer, combined with an additional workspace for tiles, contacts, music playlists, etc.

Figure 3: The new Start menu in Windows 10.

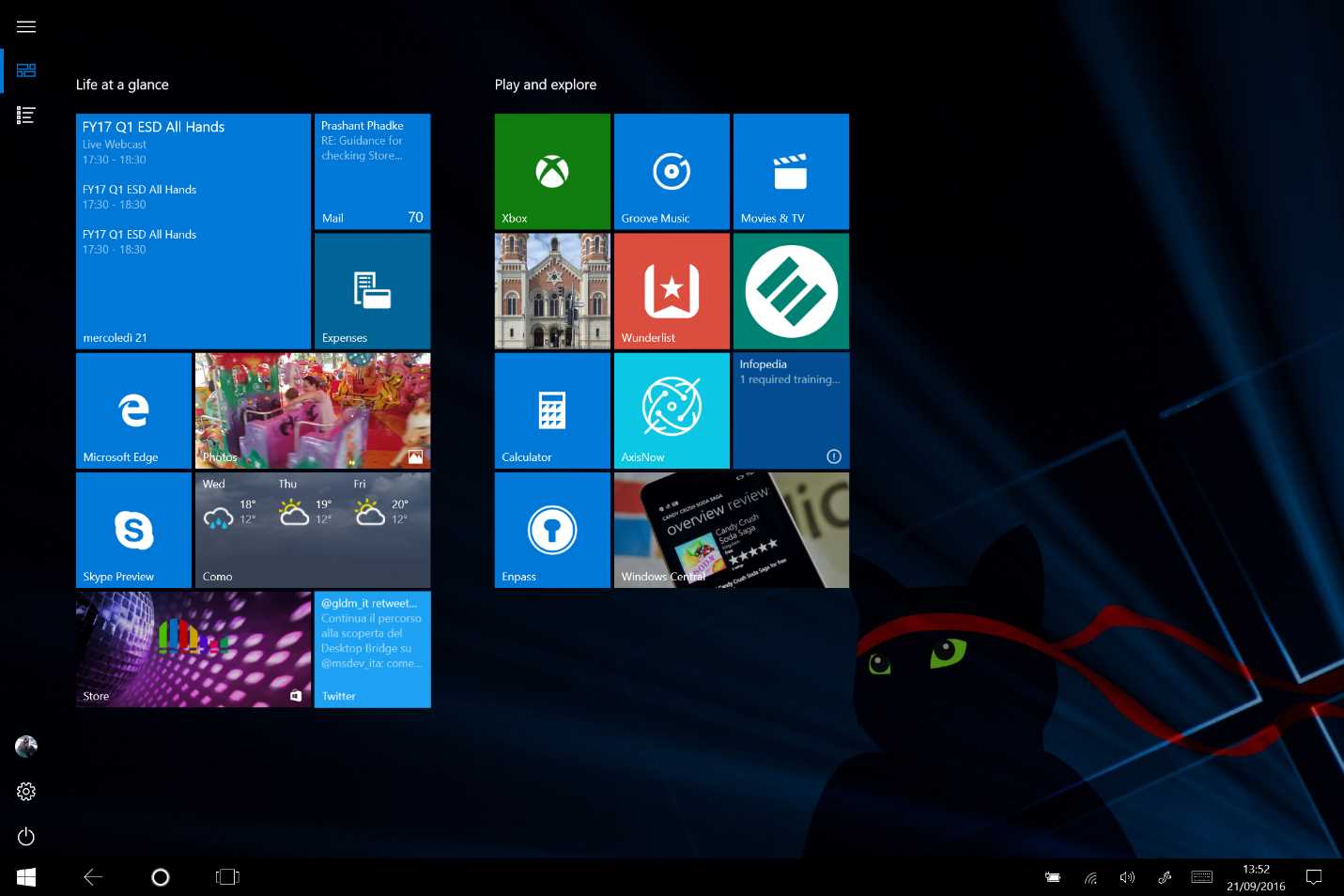

However, Windows 10 also offers a feature called Tablet Mode, which can be manually activated using an option in the Action Center or that some 2-in-1 devices (like the Surface) can automatically enable when they detect that the keyboard has been detached. When this mode is enabled, you get a fully optimized experience for touch devices, which is more like the one from Windows 8.1. Both the Start Screen and Universal Windows Platform apps are displayed in full screen, like in the following image.

Figure 4: The Start Menu when Windows 10 is running in tablet mode.

Universal Windows Platform apps

Windows 8 already introduced the concept of Windows Store apps. They were built on top of the Windows Runtime and they could be downloaded from a centralized Store, making the whole installing/uninstalling/upgrading experience easier and more like the one we find on all the major mobile platforms.

However, on Windows 8 and 8.1, Windows Store apps had a downside: they could only run in full screen mode, forcing users to lose focus on a current task when they wanted to switch from a traditional desktop application (like Word or Photoshop) to a new, modern application. Because of this, these new applications were really appreciated by users with tablets or 2-in-1 devices (equipped with a touch screen), but they weren’t used very often by owners of traditional computers with a mouse and keyboard.

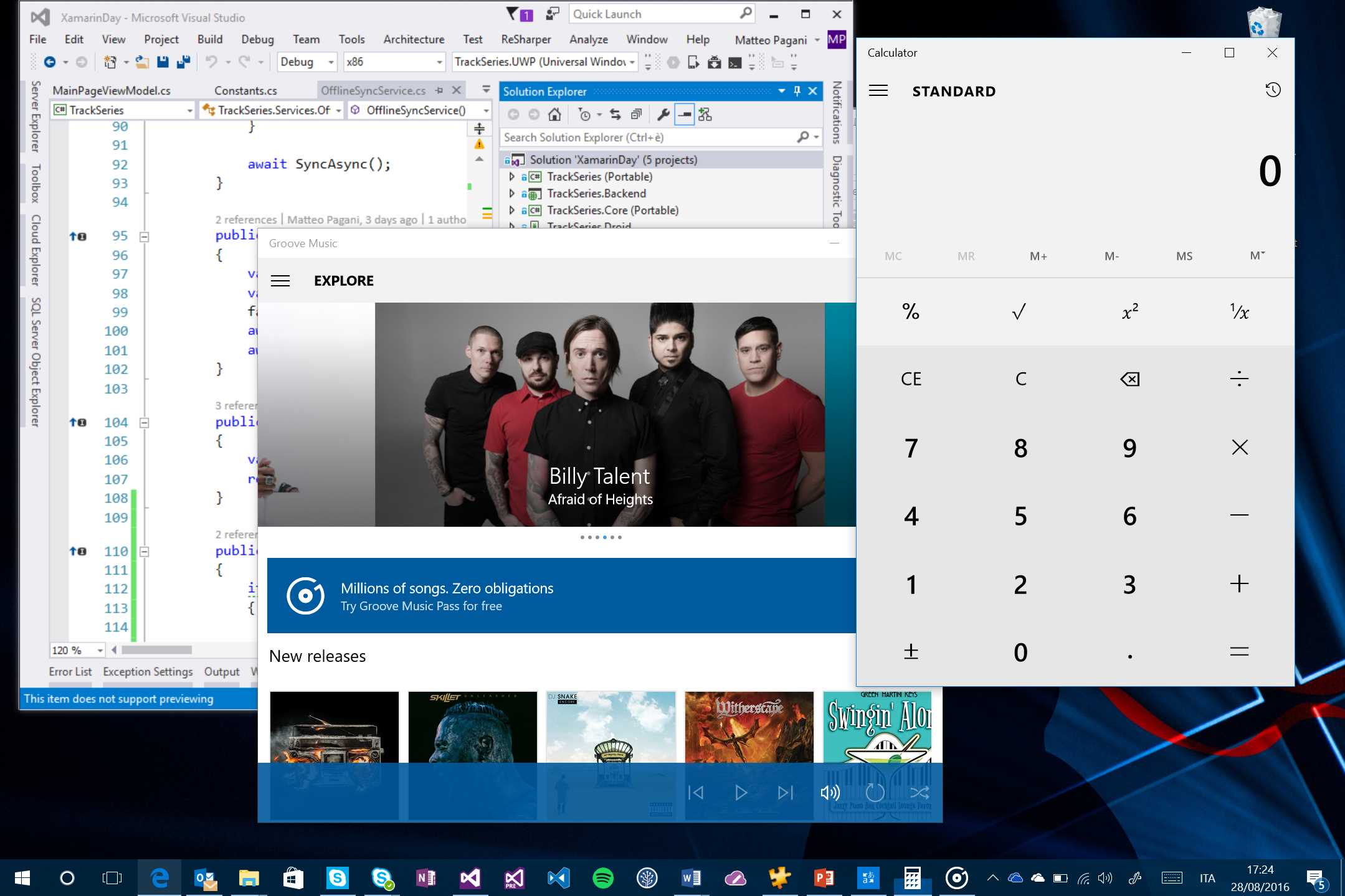

Windows Store apps (called Universal Windows Platform apps) are now capable of running inside a window, exactly like every other traditional desktop application. As such, these modern applications can be used side-by-side with traditional ones, making them much easier to use on traditional desktop computers. Additionally, Universal Windows Platform apps that run on a desktop can leverage some features that are specific to the desktop world, like supporting the dragging and dropping of content inside a window.

Figure 5: Visual Studio, which is a traditional desktop application, running side-by-side with two Universal Windows Platform apps: Calculator and Groove Music.

Action Center

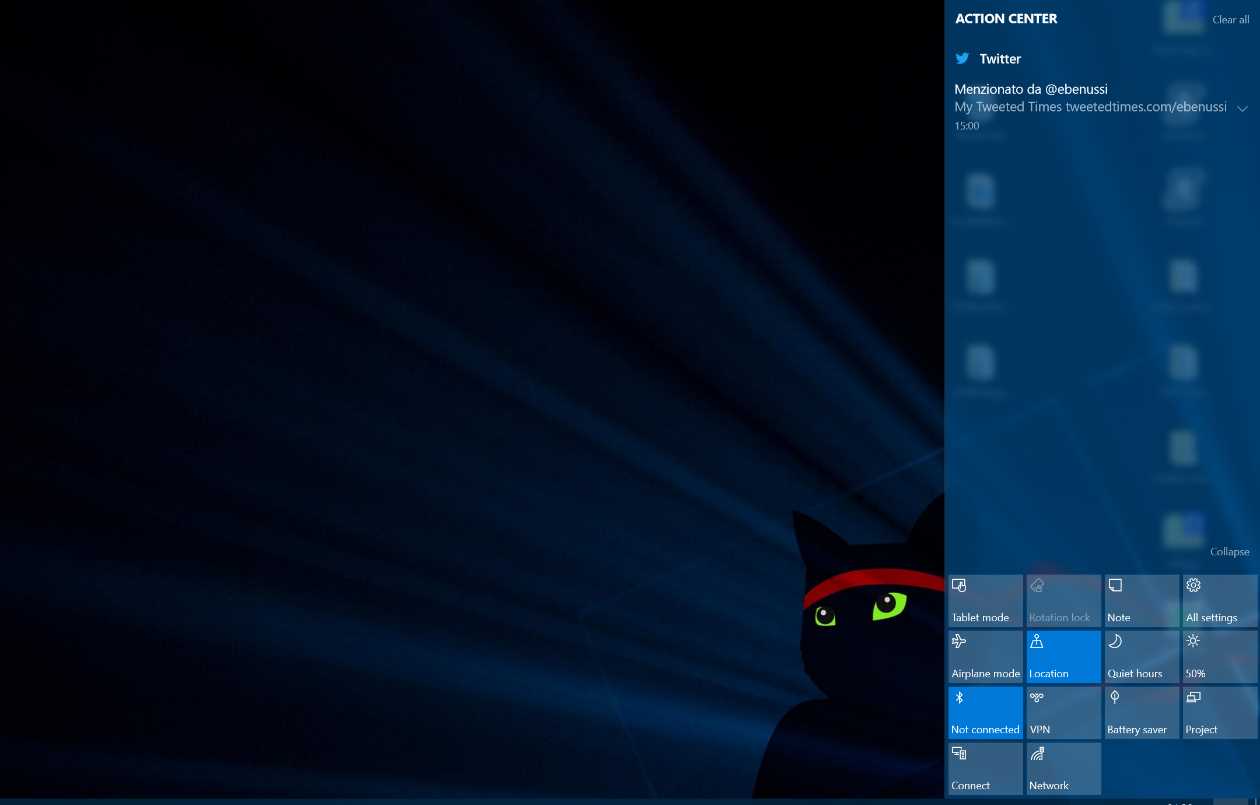

This feature is inherited directly from Windows Phone 8.1 and it’s known also as the notification center. Every time one of our applications sends us a notification (for example, when we receive a new email or a new mention on Twitter), it’s stored in the Action Center so that it doesn’t get lost because we weren’t paying attention to the screen when we received it. Additionally, the Action Center contains a set of quick action buttons to quickly turn on or off features like Bluetooth, airplane mode, VPN settings, etc.

On a desktop, the Action Center is activated by clicking an icon on the bottom right corner of the screen or with a swipe from the right side of the screen on a touch-screen device; on mobile, it’s displayed by swiping from the top to the bottom of the screen.

Figure 6: The Action Center in the desktop version of Windows 10.

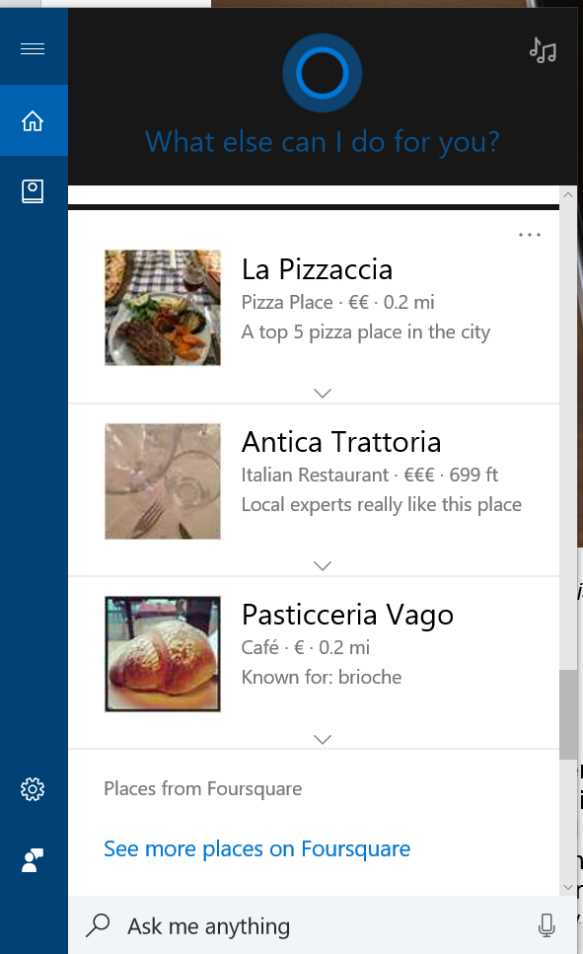

Cortana

Cortana is another new feature introduced first in Windows Phone 8.1 and later expanded to Windows 10 across all devices. Cortana is a digital assistant that we can use to quickly get information about a topic (like how much time it will take to travel from home to the office), to set reminders based on time or location, to get notifications on topics that are relevant to us, to keep track of our appointments during the day, and much more. Everything can be achieved by simply typing our requests in the search box, but we can also leverage more natural ways like voice and inking. With the anniversary update, Cortana has been further expanded, allowing users to interact with her even when the computer is locked.

Cortana is also important for developers, since we have a set of APIs to integrate her into our applications, allowing users to perform tasks just by talking and without having to open an app or unlock their devices.

Figure 7: Cortana on Windows 10 is displaying information about the best restaurants near the current location.

Microsoft Edge

Microsoft Edge is a new browser that replaces Internet Explorer as the default browser in Windows 10. Edge has been built from scratch with the goals of supporting all modern web technologies and getting rid of all the legacy code and plugins that were often the cause of security and performance issues. The philosophy behind Edge is the same as the one behind Windows 10: the virtual world is moving fast, so releasing a new version of the browser every 2-3 years wasn’t sustainable anymore, especially when the competition releases a new version of their browser every week.

Edge offers great performance, support to the most recent web standards, and, despite it using its own open-source engine (Chakra), it’s fully compatible with all the features offered by other engines like WebKit (which is used by very popular browsers like Chrome and Safari).

In this case, Edge isn’t just a consumer feature. Developers can also take advantage of its engine to create web-based applications or to integrate web features into their Universal Windows Platform apps.

Windows 10 November update (build 10586)

The November update, identified by build number 10586, was released in November 2015 and marked the first official release of the platform for mobile devices. It didn’t add any major new consumer feature, but it continued to improve the Windows 10 experience by refining the Start menu and tablet mode, by expanding Cortana into new markets, and by adding a new SDK for developers with new APIs and features, like a new animation system.

Windows 10 Anniversary Update (build 14393)

The Anniversary Update was released one year after the original Windows 10 version and it’s identified by build number 14393. This update expanded the device families that can be targeted by developers even more. This version, in fact, was also released for Xbox One, bringing some of the features of the other versions (like Cortana) and the Universal Windows Platform, and allowing apps to run on the game console. The only exception to cross-device publication is games. If you’re a game developer, your game still needs to be approved by Microsoft by submitting it through the ID@Xbox program (you can find more info on the official website).

From a consumer point of view, the Anniversary Update has added some notable features, like extensions support for Edge, notifications synchronization among multiple cross-platform devices (not only Windows 10 Mobile, but Android is also supported), and new and improved built-in apps, like a new version of Skype. Inking support has been vastly improved, too, by a set of new features (both for developers and consumers) that make Windows 10 great to use with digital pens on supported devices, like the Surface family.

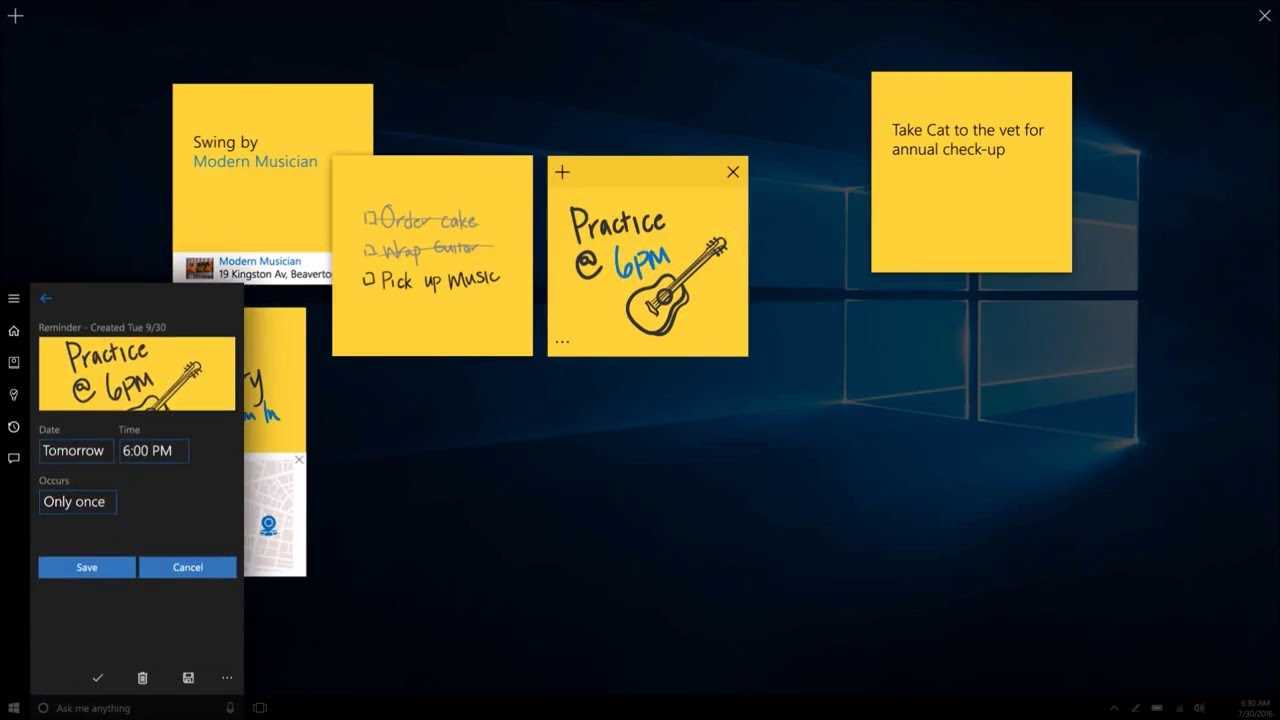

Figure 8: The Windows Ink Workspace on Windows 10 Anniversary Update.

From a developer point of view, other than the release of a new SDK with a new set of APIs, which will be discussed in detail in this book, it introduced two new important features:

- The Windows Subsystem for Linux is a user space developed by Ubuntu that runs natively inside Windows, allowing developers to use a native version of the BASH shell. This feature follows the open-source approach embraced by Microsoft, allowing developers familiar with UNIX tools to use them in a native way, without having to create a separate virtual machine with Linux. This feature, which is especially appreciated by web developers, helps to get the best of both worlds by allowing you, for example, to create a web project using a UNIX command line tool, but to edit it using a Windows tool like Visual Studio.

- The Desktop Bridge, previously known by the codename Project Centennial, is a series of tools that allow traditional Win32 apps (based on technologies like the .NET Framework, VB6, Java, etc.) to be packaged as UWP apps and to be distributed traditionally, but also on the Store, along with standard UWP applications. Thanks to Desktop Bridge, you’ll be able to bring traditional desktop apps to the Store and, at the same time, start leveraging some of the UWP APIs and features in a Win32 app without having to rewrite it from scratch as a Universal Windows Platform app.

Windows 10 Creators Update (build 15063)

Windows 10 Creators Update is the latest version of the operating system, which started the official rollout on 11th April 2017. As the name says, the main target audience of this new version are creators: other than the usual improvements to the overall operating system (like a better support to high DPI devices; a night mode that makes the computer less fatiguing to use for the eyes during the night; a more consistent Settings experience, etc.), it has added a specific new set of application and tools dedicated to makers, designers and game players and game developers.

Some of the most interesting new features are:

- Paint 3D, which is a new version of one the most famous graphic application in the world. As the name says, Paint 3D can be used to create 3D models, that can be easily exported and reused with popular tools to work on three dimensional applications.

- Windows Mixed Reality: it’s a new platform, both for consumers and developers, which brings together all the efforts to explore the new Mixed Reality ecosystem that, at first, was introduced by HoloLens and that now is being brought to the masses thanks to a new generation of devices, produced by Microsoft partners, that will make the holographic and immersive experiences merge together. Mixed reality blends real-world and virtual content to create compelling interactive experiences and, no matter if you’re going to leverage an immersive experience or a holographic one, both are empowered by the same platform, allowing:

- Developers to create three dimensional experiences that can be easily adapted and consumed with both categories of devices.

- Users, to have a common virtual experience across every headset and mixed reality experience on Windows, no matter if it’s a game or an educational application.

- Gaming: the Creators Update is the perfect operating system for gamers, by offering a set of features like Game DVR (to record a game session), Broadcasting (to stream a game session to other spectactors) or Game Mode (to focus all the hardware power of the machine on the game, so that it can run in the best possible way). Also developers can take advante of these gaming features, by offering the same game both on Xbox One and on PC; by adding a SDK to integrate Xbox Live features like achievements, leaderboard, etc.

This book is based on the Creators Update and, therefore, will cover most of the features and APIs introduced in the 15063 Build SDK.

Another important announcement related to this version of Windows is the launch of Windows 10 S, a special version of Windows 10 (based on the Creators Update) that, starting in Summer 2017, will ship on many computers and 2-in-1 devices (including a new device made by Microsoft called Surface Laptop). It’s dedicated especially to the education world and to users that want a system as much safer and fast as possible, even after years of usage. Windows 10 S, in fact, supports acquiring applications only from the Windows Store, making almost impossible for a casual user to install adwares, malwares or classic desktop applications that can slow down the system. Desktop applications, however, will still be available and downloadable from the Store, thanks to the Desktop Bridge, the technology introduced and already mentioned in the description of Windows 10 Anniversary Update.

Windows 10 also introduced a big change in the pricing model. For the first time, a Windows version was offered as a free update to all the existing Microsoft customers. For a limited time of one year (from 29 July, 2016, to 29 July, 2017), Windows 10 has been made available for free through Windows Update to every existing Windows Vista, Windows 7, or Windows 8.1 user.

The Universal Windows Platform

As already mentioned, Windows 8 wasn’t a break from the past just from the user experience point of view, but also for developer. It introduced the concept of Windows Store apps based on a new framework called Windows Runtime, instead of relying on the .NET Framework that developers had learned to use to create desktop and web apps a few years ago. It’s a native runtime that is built on top of the Windows kernel and offers a set of APIs that apps can use to interact with the hardware and the operating system. It uses a similar approach to the old one based on COM (Component Object Model), created in 1993 with the goal of defining a single platform that could be accessed with different languages.

Windows Runtime uses a similar approach by introducing language projections, which are layers that are added on top of the runtime that allow developers to interact with the Windows Runtime using well-known and familiar languages, instead of forcing them to learn and use just C++. The available projections are:

- XAML and C# or VB.NET: this projection allows you to create applications using C# or VB.NET for the logic and XAML to define the layout. It is implemented with a special subset of the .NET Framework.

- HTML and JavaScript: this is the projection that will be appreciated most by web developers, since it allows them to use web technologies to create apps. The application’s layout is defined using HTML5, while the logic is based on a special library called WinJS, which grants access to the Windows Runtime APIs using JavaScript.

- XAML and C++: this projection can be used to create native applications using a C extension called C++ / CX that makes it easier for developers to interact with the Windows Runtime using C++.

- C++ and Direct X: this projection is especially useful for games, since it allows you to create native applications that make use of all the powerful features offered by the DirectX libraries to render 2-D and 3-D graphics.

The Windows Runtime libraries (called Windows Runtime Components) are described using special metadata files, which make it possible for developers to access the APIs using the specific syntax of the language they’re using. This way, projections can also respect the language conventions and types, like uppercase if you use C# or camel case if you use JavaScript. Additionally, Windows Runtime components can be used across multiple languages. For example, a Windows Runtime component written in C++ can be used by an application developed in C# and XAML.

The Universal Windows Platform can be considered the successor of Windows Runtime and it’s built on the same technology. In fact, if you already have some experience with the development of Windows Store apps for Windows 8.1 and Windows Phone 8.1, you’ll find yourself at home. The Universal Windows Platform has added many new features and brought unification across all the platforms, but most of the APIs and features are the same as those you’ve learned to use with Windows Store apps development. This is a great news, because it helps keep the learning curve moving from Windows 8.1 to Windows 10 very gentle, unlike what happened in the shift between Windows Phone 8 with Silverlight and Windows Phone 8.1 with the Windows Runtime. In fact, at that time, the shift between the two technologies was quite radical and, despite sharing the same fundamental concepts, basically all the APIs and the XAML controls were different, forcing developers to rewrite most of the existing code base to target the new platform.

The most important feature of the Universal Windows Platform is that it offers a common set of APIs across every platform. Whether the app is running on a desktop, a phone, or a HoloLens, you’re able to use the same APIs to reach the same goals. The following image shows where the Universal Windows Platforms fits in the overall Windows 10 architecture: every device, despite having a different shell, shares the same kernel, which is the Windows Core. On top of the core, the Universal Windows Platform provides a consistent set of APIs to access to all the functionalities that are exposed by the core, like network access, storage, sensors, etc. A Windows app runs on top of the Universal Windows Platform and is a single binary package, unlike with Windows 8.1, where you had to deal with one package for the phone and one for the PC.

Figure 9: The Windows 10 ecosystem for developers.

Another important change in the Universal Windows Platform is that, when it comes to the C# and XAML project, it doesn’t leverage the standard .NET Framework anymore, but a new, modern framework called .NET Core.

.NET Core can be considered the successor of .NET Framework. It has been built from scratch by following the new Microsoft principles: open source and cross platform. The adoption of .NET Core makes it easier to reuse the parts of the code base that don’t have a specific dependency on the platform (like network communication) with other projects, no matter if it’s a web application or a traditional desktop application. However, it’s important to understand that this doesn’t mean Universal Windows Platform apps can also run on competitive platforms like Android and iOS. The Universal Windows Platform, in fact, is built on top of .NET Core and it leverages its common base, but adds a set of APIs and features which are Windows specific.

The cross-platform nature of .NET Core, at the time of writing, can be leveraged especially by web developers. Thanks to this new framework, you’ll be able to create web applications based on ASP.NET that are no longer forced to run only on a Windows server running IIS, but that can also be hosted on Linux and OS X.

This series of books is dedicated to exploring Universal Windows Platform apps development with C# and XAML. All the concepts and features that will be described in the next chapters can be leveraged by any supported language, but all the code samples published in the book will be in C# and XAML.

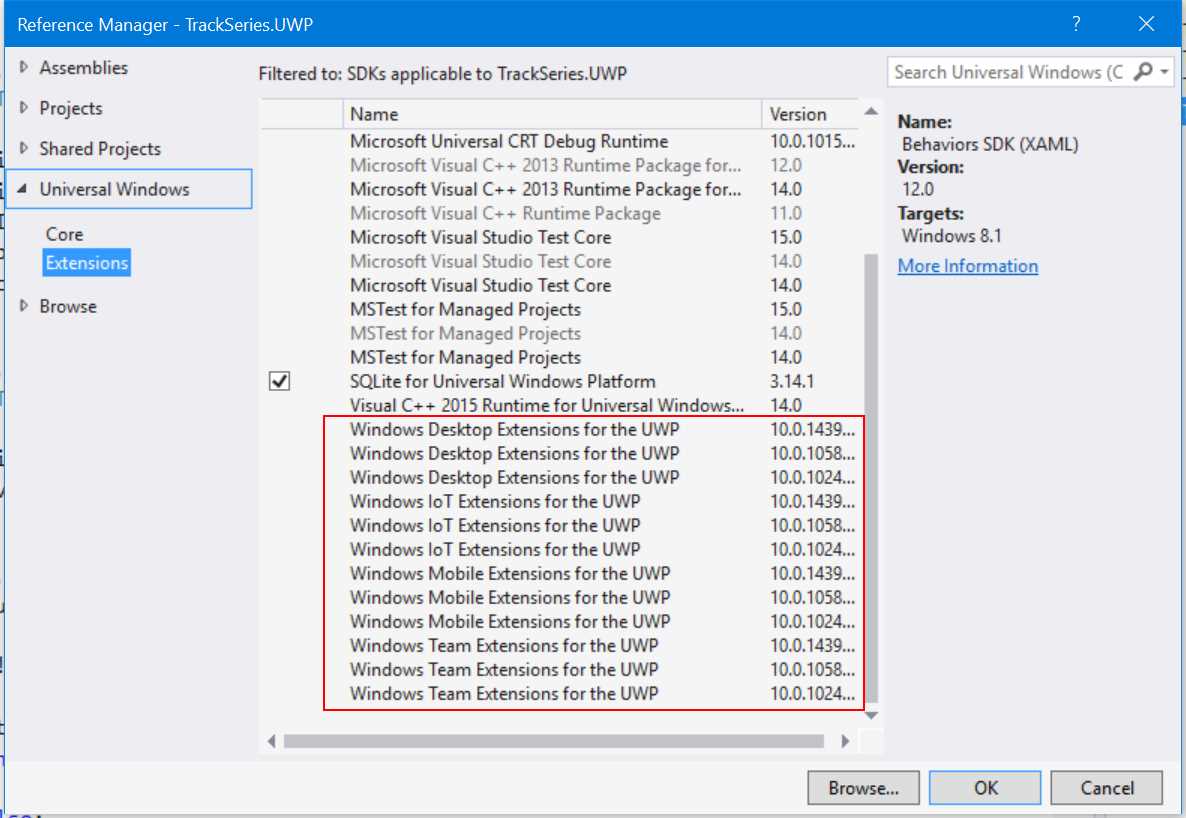

The Extension SDKs

Having a common set of APIs to target is great because it helps to maximize the code reuse across every platform. However, even if they share the same Windows Core, every device has some unique differentiators. For example, a desktop is typically controlled with a mouse and a keyboard, so a typical requirement of a desktop app is to support drag and drop; a phone, instead, can have a dedicated camera button to quickly take pictures, which is something that a PC or tablet usually doesn’t have; a Raspberry Pi 3 offers an integrated circuit (called GPIO) where you can connect various sensors and devices, like LEDs, temperature sensors, or humidity sensors, but this is something that only an IoT device can offer and you won’t find it on a PC or phone.

How does Windows 10 handle the fact that it has a common set of APIs for every platform (the Universal Windows Platform), but must still allow developers to take advantage of the specific features offered by each of them?

The answer is extension SDKs, which is a set of additional libraries that can be added in a UWP app directly through Visual Studio and that contain a set of APIs that are specific for each platform. As such, you will find a Windows Desktop Extensions library, a Windows IoT Extensions library, etc.

Figure 10: The various extension SDKs available for the Universal Windows Platform.

The APIs contained in these extensions are available in the base Universal Windows Platform. Consequently, even if you’re going to add one or more of them to your project, you’ll always be able to compile it without issues. However, on all the platforms that don’t support these APIs, they aren’t really implemented: you can think of them as stub APIs. They’re declared, the various classes and methods are available, but they’re not really implemented. Consequently, they will work only on the platforms for which they’ve been designed. If you try to execute some platform-specific code (like access to the camera button) on a platform which doesn’t support it (like a desktop computer), you will get an exception at runtime.

To properly handle extensions SDKs, we need to introduce another concept that will be familiar to those of you who have some experience with web development: capability detection. In the beginning of the new web era, when technologies like JavaScript, HTML5, and CSS3 opened powerful new possibilities, developers started to leverage techniques like browser detection to test if it was possible to execute some code or use a specific HTML5 feature. However, this approach soon started to show its limits: browsers started to move very fast, with companies like Google and Firefox releasing a new version every week. It was impossible for a web developer to maintain a website that needed to check every available combination of browser and version. Consequently, the web has started to move from a version detection approach to a capability detection approach. Instead of detecting the browser’s type and version, developers started to check if a specific capability (for example, video playback without plugins) was supported. This way, the website started to become independent from the browser. If a new version of Microsoft Edge or Google Chrome decided to implement a feature that the website was using, it would automatically start to work.

The same exact approach can now be applied to Windows 10. With the Windows as a Service model, it doesn’t make sense anymore to check if the app is running on a specific build, because features and API implementation can quickly change between each version. As such, developers are now required to check, instead, if an API is properly implemented on the platform on which the app is running.

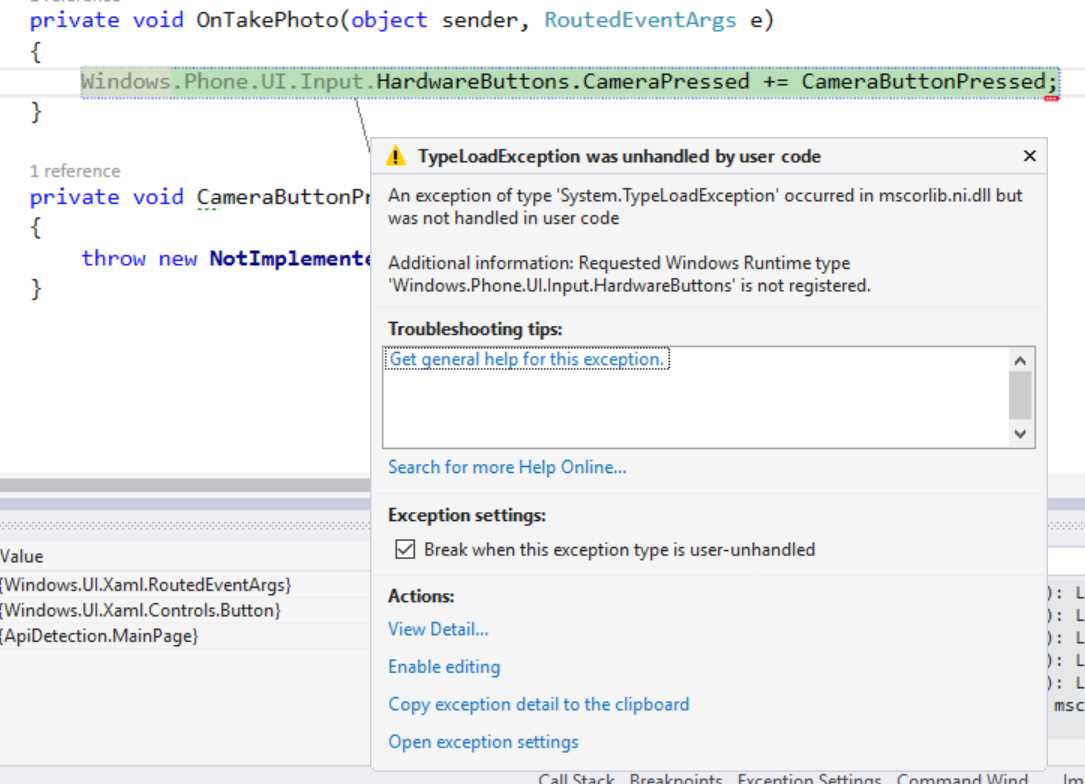

For example, let’s say that you have created a powerful photo editing application that, only when it runs on a phone, should be able to leverage the physical camera button to quickly allow users to take a photo. In the old Windows world, we would have written some code like the following one:

Code Listing 1

Windows.Phone.UI.Input.HardwareButtons.CameraPressed += CameraButtonPressed; |

The Windows Mobile Extension for the UWP offers a class called HardwareButtons, which is part of the Windows.Phone.UI.Input namespace, that allows you to handle the different buttons available on a phone. One of them is the camera button, so we can simply subscribe to the CameraPressed event and declare an event handler that will contain the code to acquire the photo when it’s triggered.

However, if your app is running on a desktop or Xbox One, as soon as it starts, it will raise an exception like the following one:

Figure 11: The exception raised when you try to use an API that isn’t supported by the current device.

This is because the HardwareButtons class is available in the Universal Windows Platform (otherwise, your project won’t be able to compile, since the binary package is universal), but it isn’t implemented on the desktop.

This is where the capability detection concept comes in. The Universal Windows Platform includes a set of APIs that can be used to detect, at runtime, if an API is available and implemented. As such, before using a platform-specific API, you will always have to call these APIs to detect if the feature is really supported.

This API is called ApiInformation and it’s part of the Windows.Foundation.Metadata namespace. It offers many methods to check various types of implementation and conditions. In the case of a simple API like the previous one, we need to use a method called IsTypePresent(), passing as parameter a string with the full namespace of the class we’re trying to use. Here is how our previous code should look in a proper UWP app:

Code Listing 2

string api = "Windows.Phone.UI.Input.HardwareButtons"; if (Windows.Foundation.Metadata.ApiInformation.IsTypePresent(api)) { Windows.Phone.UI.Input.HardwareButtons.CameraPressed += CameraButtonPressed; } |

The method (like every other method offered by the ApiInformation class) returns a bool that will tell you if the feature you’ve requested is implemented or not. In the previous sample, we’re going to subscribe to the CameraPressed event handler only if the app is running on a platform where the HardwareButtons class is implemented.

If you think again about the web scenario previously mentioned, it should be clear the advantage of this approach. At any point in time, if another Windows 10 platform should decide to start supporting an API, your application will be ready to handle it, without requiring you to change the code and release an update.

Handling the different versions of Windows 10

The Windows as a Service approach introduces a challenge that, as developers, we didn’t have to face before. In the past, when we started to create an application, usually we targeted a specific version of Windows. If we created a Windows Phone 8.1 application, it couldn’t run on Windows Phone 8.0. Additionally, we knew exactly which features and APIs we were allowed to use, because we were targeting a specific version of the operating system with its own SDK and set of APIs.

The new Windows 10 approach introduces, instead, a potential fragmentation issue. When we create an application, we target a specific Windows 10 SDK, but we don’t know in advance which version of Windows 10 the users will have on their devices.

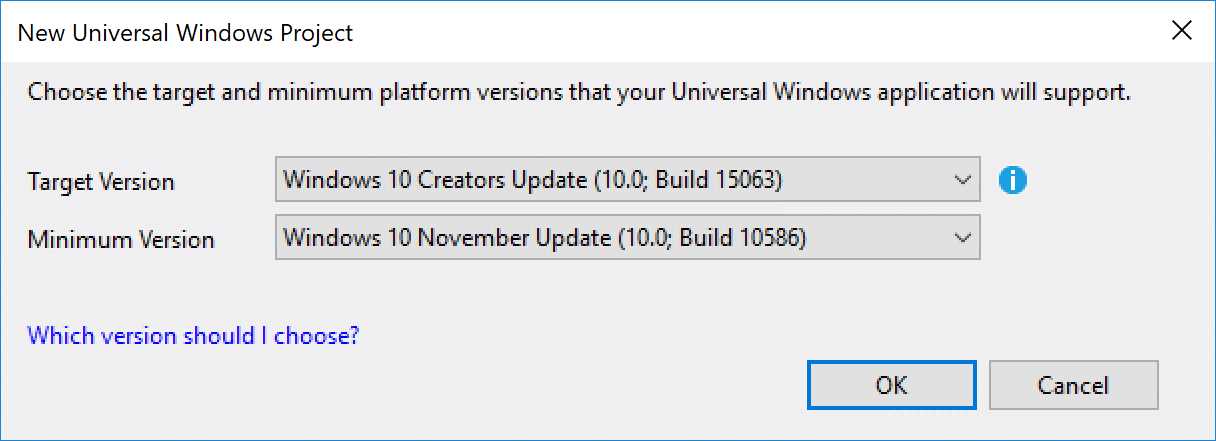

Also in this case, exactly like we did with extensions SDKs, we can leverage capability detection to solve this problem. When you create a new Universal Windows Platform app in Visual Studio, this is the message dialog you’re going to see:

Figure 12: The dialog displayed when you create a new Universal Windows Platform app in Visual Studio.

As you can see, you can set a Minimum Version and a Target Version for your application. The first parameter defines the minimum Windows 10 version supported by your app. If the user has a build older than the minimum one, they won’t be able to install the application at all. The second parameter, instead, defines the set of APIs that your app can leverage. If the app is running on a device with the same (or a newer) version of the target SDK, it will be able to leverage all the features included in the SDK.

The previous image shows the default configuration when you create a new project in Visual Studio 2017 with the Creators Update SDK installed:

- The minimum version is set to Windows 10 build 15063 (Creators Update).

- The target version is set to Windows 10 build 10586 (November Update).

This means that the application can run on devices with the November Update, but if it’s running on a device already using the Creators Update, you can take advantages of the new APIs and features included in this version. From a code point of view, you can handle this scenario in the same way we did before with Extension SDKs. You will use the ApiInformation class before using a feature that is available only on the Creators Update, otherwise people who are still running the November Update will face a crash as soon as they try to use this feature.

For example, the following sample code shows how to leverage a feature connected to animations that has been added in the Anniversary Update, but avoid the app crashing when it’s running on an older device.

Code Listing 3

if (ApiInformation.IsTypePresent("Windows.UI.Xaml.Media.Animation.ConnectedAnimationService")) { ConnectedAnimationService cas = ConnectedAnimationService.GetForCurrentView(); cas.PrepareToAnimate("ImageSeries", imgSeries); } |

Additionally, to mitigate the fragmentation issue, Microsoft has adopted a new update strategy. In the past, Windows users could disable Windows Update and decide not to keep their computer up-to-date with the latest patches and fixes. This approach has always been discouraged by Microsoft, especially for security reasons. In a world where malicious developers keep trying to steal data from users or to invade their privacy, it’s critical to keep the operating system always up-to-date with all the latest patches.

With Windows 10, only the enterprise users (who have installed Windows 10 Enterprise) can control the update cadence, because we are typically talking about a Windows edition that is usually installed in complex environments like big enterprise companies, with many legacies but critical apps that need to be tested against every Windows update to make sure that everything continues to run just fine. Windows 10 Home and Pro users can defer updates, but just for a short period of time; they can choose the date and time that best fits their needs (to avoid the update process starting in the middle of an important task); however, they can’t decide not to install a Windows 10 update. As such, it may take a while a before every user is aligned on the same version (since, typically, Microsoft deploys Windows 10 updates with a gradual rollout, to minimize potential deployment issues), but, at some point, every Windows 10 user will be on the same version. This approach gives developers the confidence that, in a short amount of time after the release of the new update, they’ll be able to leverage all the new features and APIs in their apps.

.NET Native

Another important feature introduced in the Universal Windows Platform is .NET Native. During the old Windows Phone times, the application’s build process was the typical one offered by the .NET Framework, which leveraged just-in-time compilation. This means that the Visual Studio output was a package containing intermediate code, which was converted into native code at the first execution of the app directly on the device (in the initial versions of the platform) or on the cloud (with the Windows Phone 8.1 release).

.NET Native is a new technology that allows you to compile your Universal Windows Platform app directly in native code, introducing many advantages:

- Better performance

- Quicker start-up times

- Smaller memory footprint

The downside of .NET Native is that it makes the debugging experience more complex, because the code isn’t managed anymore and, as such, stack traces are much harder to decipher. Additionally, native compilation requires longer build times than managed compilation. Therefore, by default, when a project is set in Debug mode in Visual Studio, it will be compiled in the traditional way, giving you the usual great debugging experience and fast building times. .NET Native will kick in only when you’re going to perform the compilation in Release mode, which typically happens when you’re ready to release the application on the Store or to distribute it in your enterprise environment.

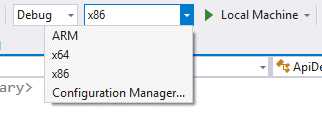

However, there’s an important aspect of .NET Native to keep in mind. If you have some previous experience with Windows Store apps development, you’ll remember that you could build your application using as target platform Any CPU. With this configuration, you ended up with a package that was cross compiled for multiple architectures and could run on any device, whether it was based on a x86, x64, or ARM architecture.

This is a specific feature allowed by the managed architecture. Native code, instead, can’t be cross compiled. Because of this, in Universal Windows Platform apps, you won’t find the Any CPU platform in the project’s configuration anymore, but you’ll have to choose the correct platform based on where you are deploying your application (for example, x86 if you’re testing it on a desktop or ARM if you’re launching it on a phone or on a Raspberry Pi).

Figure 13: The AnyCPU configuration isn’t supported anymore by Universal Windows Platform apps.

However, as we’re going to see in last part of this book’s series, this requirement doesn’t change the way we’re going to distribute our application on the Store. Thanks to a feature called package bundle, we’ll be able to create a single package that will include the application compiled against each architecture, and then it will be up to the Store to distribute to the user the proper version based on the user’s device.

The development tools

The tool to develop Universal Windows Platform apps, which has already been mentioned multiple times, is Visual Studio. The most recente version is Visual Studio 2017, which is the version you need if you want to target the Creators Update SDK. Visual Studio 2015 too supports the development of Universal Windows Platform apps, but the maximum supported SDK is the Anniversary Update (14393) one. Both Visual Studio 2015 and Visual Studio 2017 are available in different versions:

- The Community Edition, which can be downloaded from http://www.visualstudio.com/en-us/products/visual-studio-community-vs. It’s a completely free version with the same features offered by the Professional one and can be used by individual developers, students, open-source project developers, and small companies.

- Two versions dedicated to professional developers and companies, called Professional and Enterprise, which can be purchased individually or through an MSDN subscription. These give you access not just to Visual Studio but also to the whole range of Microsoft products for development and testing purposes, plus many more benefits (like monthly credit on Azure, a free token to create a developer account for the Store, etc.)

However, regarding the Universal Windows Platform apps development experience, you won’t find any difference or limitation in the Community version. You’ll be able to create and publish apps in the same way you can with a professional Visual Studio version. If you’re a student, you can also check the DreamSpark program, which allows you to get all the Microsoft professional tools for free.

Since this book is about the latest version of Windows 10, the Creators Update, we will use as a reference the most recent version of Visual Studio, which is the 2017 edition. This new version is a big step forward compared to the previous versions, thanks to a more lightweight installer (which easily allows a developer to install only the tools he needs) and a more agile development approach (which means more frequent updates, in order to fix more quickly the bugs identified by the community).

Figure 14: Make sure to check the Universal Windows App development tools in the Visual Studio 2017 setup to install everything you need to start developing UWP apps.

Of course, the best environment to start developing Universal Windows Platform apps in is Windows 10. However, the Universal Windows App Development Tools can also be installed on Windows 8.1 or Windows 7, with the following limitations:

- On Windows 8.1, the XAML designer doesn’t work and you must deploy the app on a remote device (like a Windows 10 tablet or a Raspberry PI 3), on a Windows 10 Mobile phone connected through the USB cable, or on the Windows 10 Mobile emulator. You can’t launch the app locally, since Windows 8.1 doesn’t include the Universal Windows Platform.

- On Windows 7, in addition to the same limitations you have on Windows 8.1, you can’t use the Windows 10 Mobile emulator, since it’s based on a technology (Hyper-V) that was introduced for the first time on a consumer version of Windows in Windows 8.1.

The minimum hardware requirements are a computer with a 1.6 GHz processor, 1 GB of RAM, and at least 4 GB of free space on the hard disk. If you are planning to use the Windows Mobile emulators, however, you will also need:

- A Professional or Enterprise Windows 10 64-bit version.

- A processor able to support SLAT, which is a hardware chip required by Hyper-V, the Microsoft virtualization technology developed by Microsoft used to run emulators. The post published at http://blogs.msdn.com/b/devfish/archive/2012/11/06/are-you-slat-compatible-wp8-sdk-tip-01.aspx will show you how to detect if your CPU supports this feature.

- At least 4 GB of RAM (8 GB are suggested if you’re planning to run multiple emulators at the same time).

Additionally, Microsoft has released a special version of Visual Studio 2017 called Visual Studio Preview, which contains all the new features and extensions that are still in testing phase. This version can be installed side by side with the regular version, allowing you to test the new features and, at the same time, to keep your development environment for production clean and stable. You can download the Preview version from https://www.visualstudio.com/vs/preview/

Testing your apps

Assuming that you are following the easiest path to configure your development environment, which is installing Visual Studio 2017 directly on a Windows 10 machine, there are multiple ways to test your applications, based on the target device.

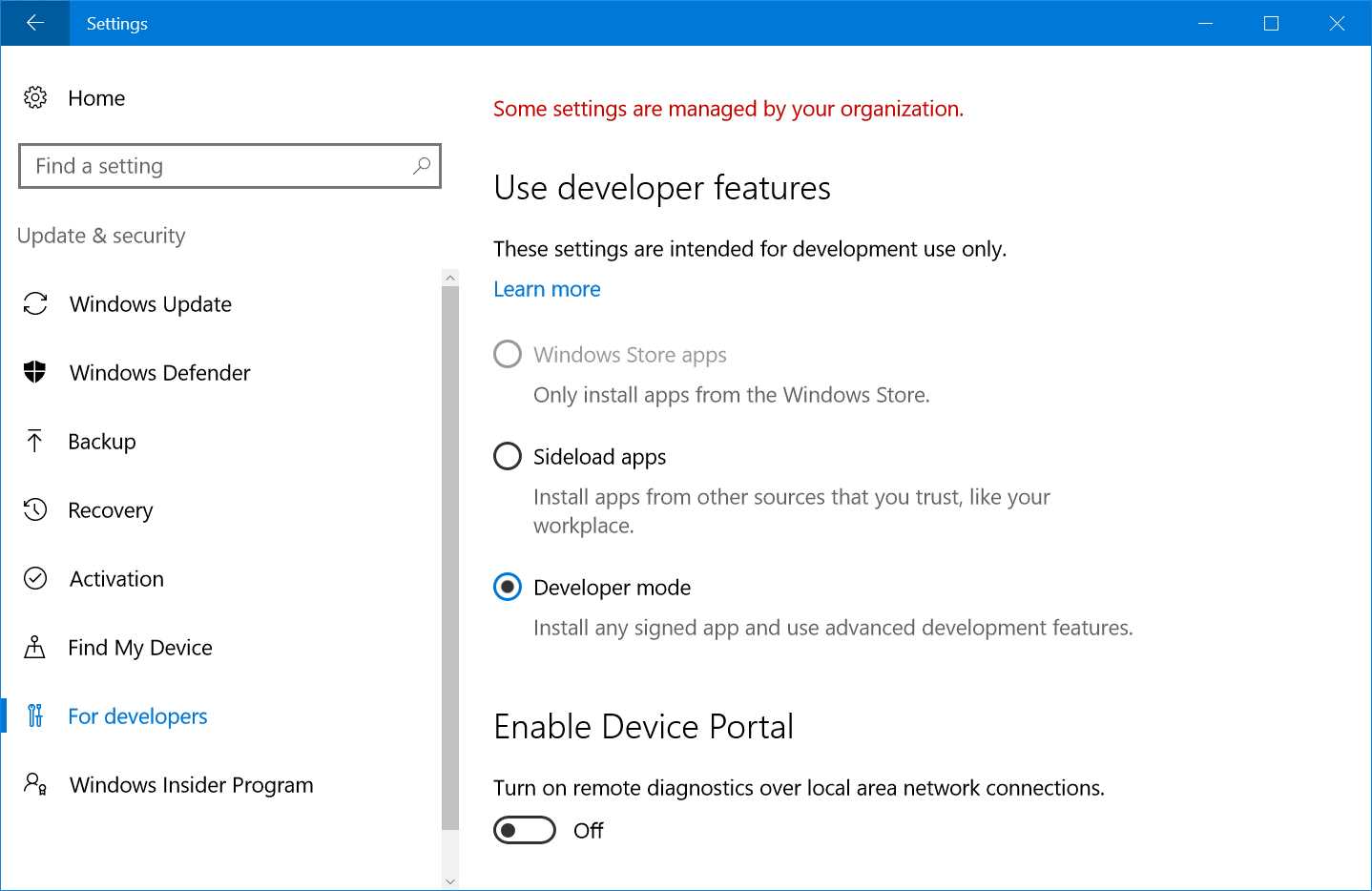

Traditional desktop or tablets

To test your app on a traditional desktop or tablet, the easiest option is simply to launch the debugger on the same machine Visual Studio is installed on. To use this approach, the computer needs to be unlocked for development, which can be achieved simply by opening the Windows settings, choosing Updates & Security, and enabling the Developer mode option under the section For developers. After this step, you can just choose Local machine as target in the debugger drop-down in Visual Studio to launch your application locally.

Figure 15: How to enable the Developer mode in Windows 10.

In case you want to test some features that your development machine doesn’t have (for example, if you don’t have a touch-enabled device like the Surface Pro), you can install the app on another device (like a Windows 10 tablet) and use the Remote Tools for Visual Studio 2017, which can be downloaded from https://www.visualstudio.com/downloads/ under the Tools for Visual Studio 2017 section. Once you have installed it, you’ll be able to connect to this device from your development machine. The only requirement is that they should be on the same network. To use this approach, you’ll have to choose the option Remote machine as target in the debugger drop-down. You’ll be asked some information about the target device, like its IP address or network name.

Another option is to use the Simulator, which is a special application that will launch a remote desktop session against your existing Windows installation. The advantage of the simulator is that it offers a set of tools to simulate scenarios that can be hard to test with a physical machine, like network speed, geolocation, or different resolutions and scaling factors.

Smartphones

If you want to test the mobile version of your app, you can use a physical Windows 10 Mobile device, like a Lumia 950 or a Lumia 550. You will have to first unlock the device for development. Since Windows 10 shares the same core and the same user experience across every platform, you can follow the same steps described for the desktop to enable the Developer mode on a mobile phone.

Deployment and debugging is supported only by connecting the mobile phone to the development machine with a USB cable; then, you can choose Device from the debugger drop-down in Visual Studio 2015.

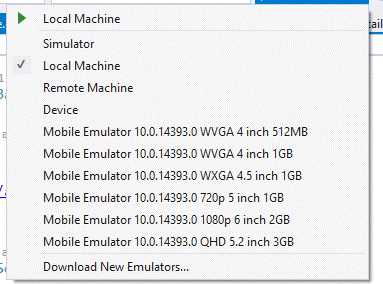

Another option, if your machine supports it (see the requirements in the previous section), is to use the Windows 10 Mobile emulator, which supports a set of additional features that make some scenarios easier to test. For example, you can fake the device’s location (to test apps that make use of geolocation services), you can simulate incoming notifications or an SD card, you can test different network conditions, etc.

To deploy and debug your application on a Windows 10 Mobile emulator, you can choose one of the available images in the debugger drop-down. There are multiple versions of the emulator to simulate different screen sizes and hardware features (like high-resolution screens or low-memory devices).

Figure 16: The various emulators available to test your apps on a Windows 10 Mobile device.

Windows 10 IoT Core

Windows 10 IoT Core comes with a special version of the Remote Tools for Visual Studio 2017 already installed, which is started by default when you boot the device. As such, to deploy and debug a UWP app on Windows 10 IoT Core, you must choose the Remote machine target in the debugger drop-down menu and specify the IP address or network name of your IoT device, which needs to be connected to the same network of the development machine.

HoloLens

From a testing point of view, HoloLens is a mix of all the other testing modes we’ve seen so far:

- You can deploy your application directly on the device by connecting it to the PC using a USB cable. In this case, you choose Device as target, like you would do with a Windows 10 Mobile phone.

- You can deploy your application remotely by choosing as target Remote machine and specifying the IP address of the HoloLens.

- You can also test them against an emulator. However, unlike the mobile emulator, the HoloLens one isn’t automatically installed with Visual Studio, so you’ll have to install it separately from https://developer.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/holographic/install_the_tools.

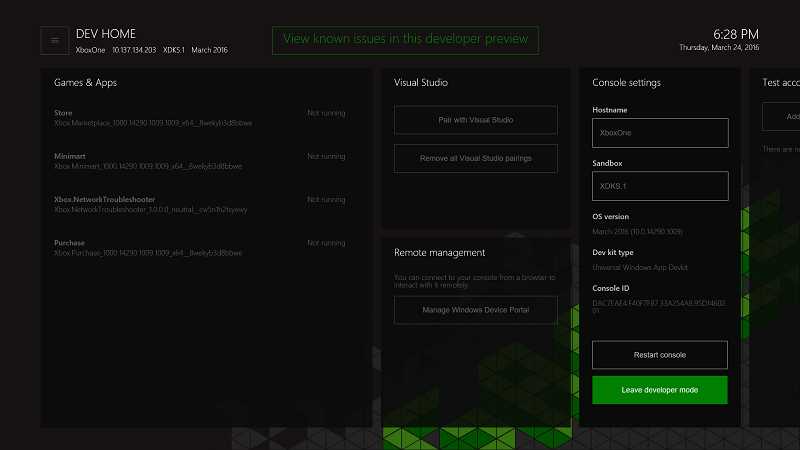

Xbox One

The developer mode isn’t built-in in the console, but requires a separate app to be installed and launched directly on the console. The app is called Dev Mode Activation and you’ll have to search for it on the Xbox One Store. Once you have installed and launched it for the first time, the app will give you a code, like in the following image:

Figure 17: The code to activate the development mode on Xbox One.

Once you have the code, you can open your browser on your PC and head to the URL: https://developer.microsoft.com/xboxactivate. It will take you to a specific page of the Dev Center (the portal where you submit and manage your applications we’ll talk about it in the second part of the book) where you insert the code.

At this point, your Xbox One will be unlocked and, by using the Dev Mode Activation app, you’ll be able to switch your console from the standard retail mode (where you can play games, use apps, chat with your friends, etc.) to the dev mode, which will launch the Remote Tools for Visual Studio 2017. After that, the procedure to debug your UWP app on the console is the same we’ve seen, for example, with an IoT core device. You’ll have to choose the option Remote machine from the debugging drop-down and specify the IP address of your Xbox One (which will be displayed directly, together with other info, on your TV screen once your console is in dev mode).

Figure 18: The Development Mode home on Xbox One.

Surface Hub

Testing and debugging apps on Surface Hub works like on an IoT Core device. Also, Surface Hub comes equipped with the Remote Tools for Visual Studio 2017, which are automatically launched when the device boots. As such, you must choose the Remote machine option from the debugging drop-down and specify the IP address of the Surface Hub.

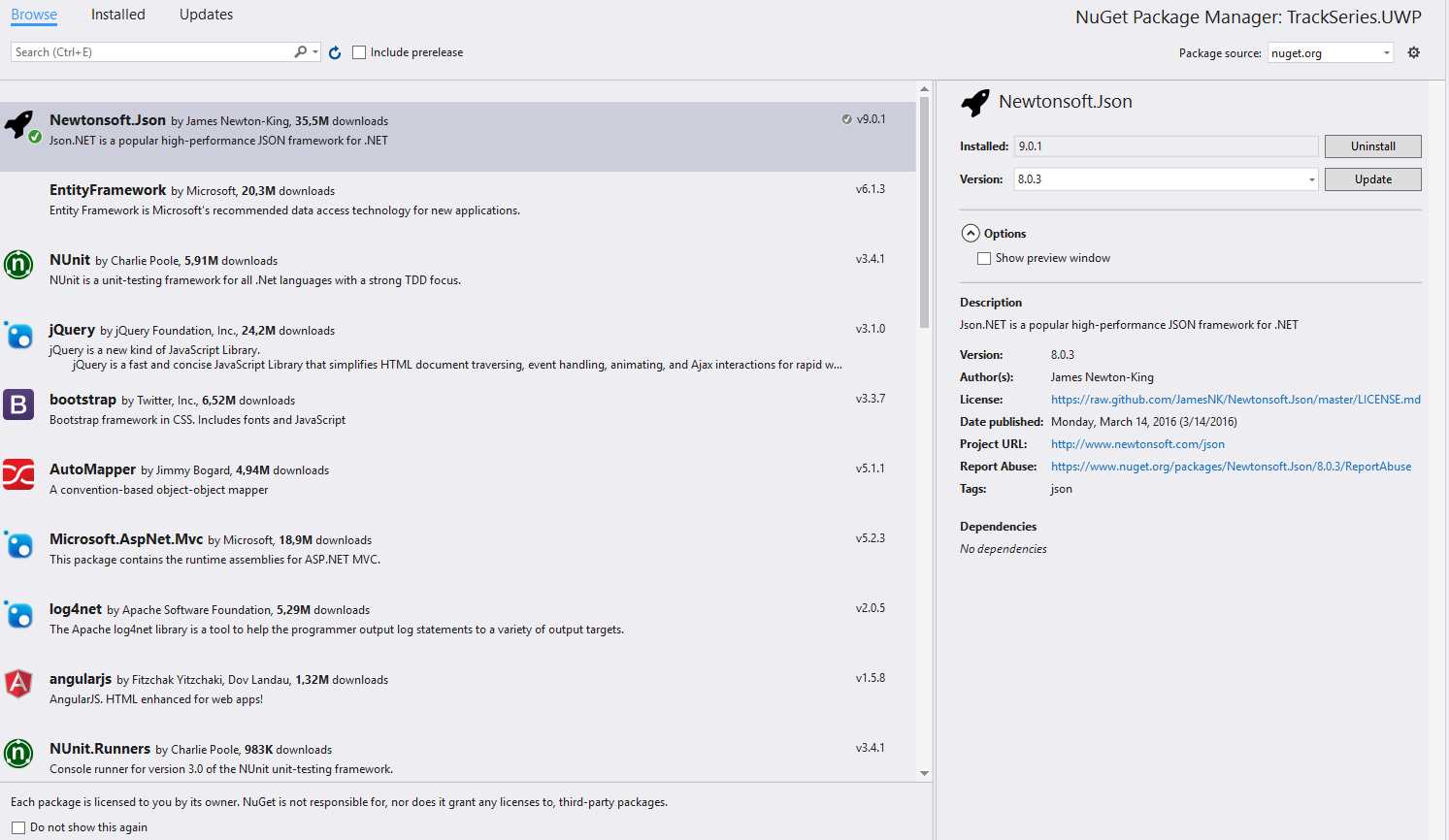

Using NuGet

NuGet is a popular package manager that simplifies the developer’s life. When it comes to adding a third-party library to our project, instead of searching the web and then downloading and manually adding a reference in our project, we can use NuGet to perform all these operations for us. NuGet will take care of downloading the library, adding a reference to the proper DLL (or DLLs), and setting up the project with all the required files and configurations.

NuGet is becoming more and more part of the integrated development experience in Microsoft, with the goal being to reduce the dependencies of a platform from its libraries and tools. A NuGet package, in fact, can be updated more frequently and independently from Windows and Visual Studio. For example, the base .NET Core version that the Universal Windows Platform is based on is a NuGet package itself that the Windows team can update independently from Windows 10 and Visual Studio. It’s likely, in fact, that when you create a new Universal Windows Platform project, you will immediately find an update for the package Microsoft.NETCore.UniversalWindowsPlatform to apply (which is highly recommended, since it will allow you the benefit of all the improvements that have been made to .NET Core).

We’re going to use NuGet in many scenarios in these books to install third party libraries that can simplify our job. Using NuGet is simple: right-click on your project and choose the Manage NuGet packages option. You will a see the NuGet main window, which you can use to find new packages on the core repository, uninstall an already installed package, or update an existing one. You can also access an option called Manage NuGet packages for Solution by right-clicking on the solution. In this case, you’ll be able to manage the packages that are installed on every single project.

To add a package, it’s enough to search for it by name or by a keyword in the Browse tab. After you’ve found it, just click the Install button displayed near the package description. NuGet will take care of everything for you.

Figure 19: The NuGet window to handle the libraries installed in a Visual Studio project.

The package manager has also two additional tabs: Installed will list all the packages that have been installed to the current project or solution, while Updates will display available versions newer than the one currently installed.

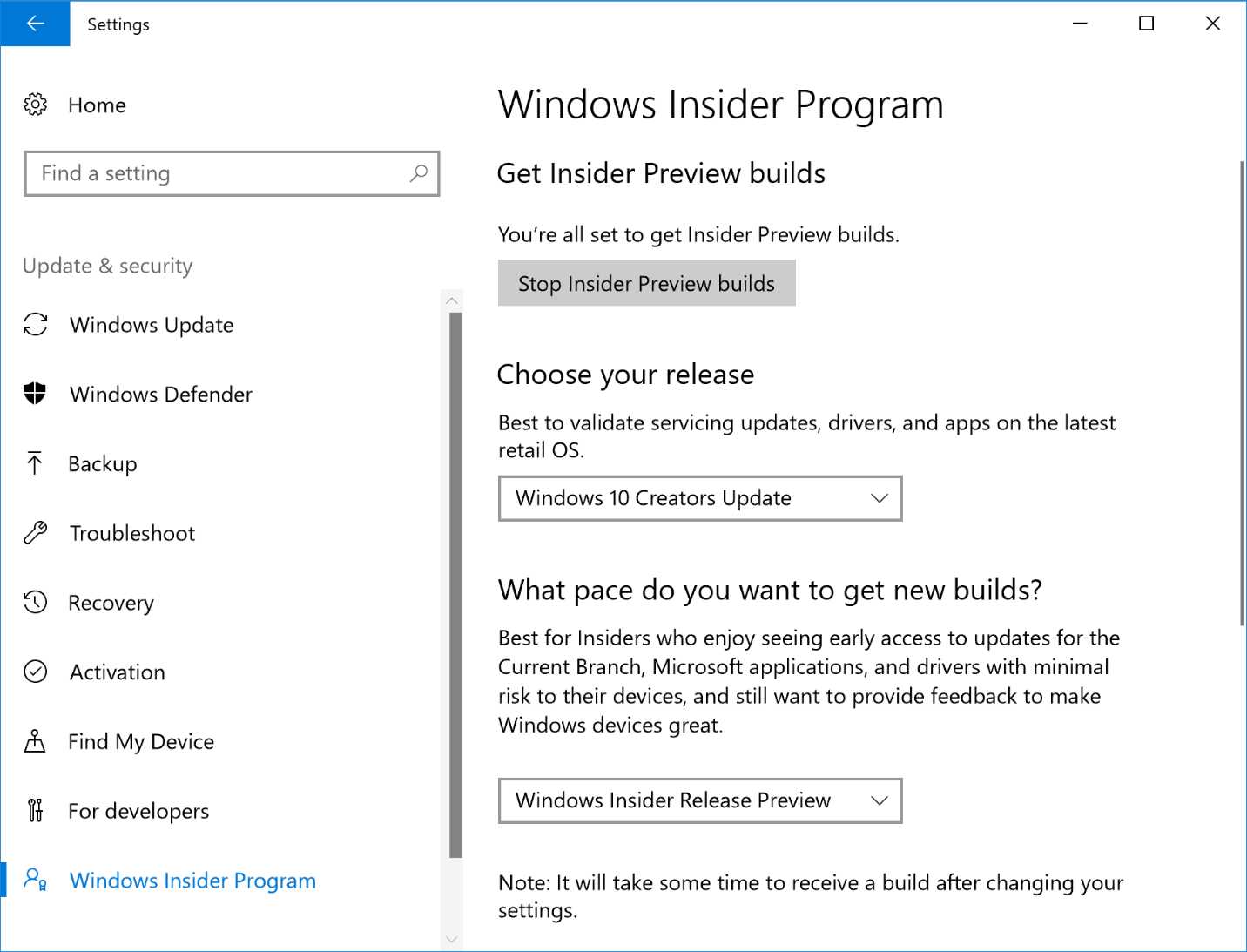

The Windows Insider program

With Windows 10, Microsoft also started a new approach to getting feedback about the new releases of the operating system by launching the Windows Insider program, which is available for many platforms (the two most frequently updated ones are for desktop and mobile, but you will find Insider builds also for IoT Core).

When you subscribe your device to the Windows Insider program, you have the chance to get early builds of the new versions of the operating system and test all the upcoming features before the final the release. This program targets not only consumers, but also developers. Developers subscribed to it, in fact, have the chance to get early access to preliminary versions of the new SDKs, to start experimenting with new APIs and scenarios.

The program helps enthusiastic users and developers stay always up-to-date on the latest features and announcements, but it also helps Microsoft to shape Windows 10 in a better way. Many decisions made by the engineering teams during the development of various Windows 10 updates are a direct consequence of the feedback reported by the Insider users through the Feedback Hub, a built-in application that, previously, was available only in the Insider builds but, starting from the Anniversary Update, can be leveraged by every user to share feedback about the platform.

To subscribe to the Insider program, it’s enough to open the Settings on your device and, in the Updates & Security section, choose the Windows Insider Program tab. From there, you’ll be able to connect your Microsoft account to the program, turning your Windows installation into a Windows Insider machine. The Windows Insider Program offers three different rings, which you can select from in a drop-down menu in the same branch:

- Fast Ring: with this ring, you’ll receive a new build approximately every week. You’ll be the first to test new features as soon as they are introduced, but you’ll also more likely encounter some issues, since these builds can be very preliminary and not fully tested.

- Slow Ring: with this ring, you’ll receive a new build approximately every month. It will take a while (compared to the fast ring) before you’ll start to see new features, but the average quality of these builds will be higher, since they’ve gone across multiple test cycles and they’ve been released in the fast ring for a while.

- Release Preview: with this ring, you won’t receive new major versions, but only cumulative updates for your current version, usually a couple of weeks before they’re released to all other users.

The main difference between the first two rings and the Release Preview ring is that:

- Fast and slow rings release Windows 10 versions with a completely new build number, which means that they will trigger a full upgrade experience. For example, at the time of writing, the fast ring contains the first releases of the next Windows 10 version, which name, announced during the BUILD conference, will be Fall Creators Update. The build number of these releases starts from 16100.

- Release preview ring contains only updates that change the minor revision of the build, which on PC are applied as regular patches and they just require a reboot. On the phone, instead, the update procedure is always the same, regardless of whether it’s a major or minor build. For example, at the at the time of writing, the release preview ring contains build 15063.296 (as you’ll notice, the major revision number is still 15063, the one related to the official Creators Update). The number that changes refers to the minor revision, which I have highlighted in bold.

Figure 20: The Windows Insider Program page in the Windows settings.

The future of the Universal Windows Platform

During the BUILD conference in Seattle, in early May, Microsoft has unveiled some important announcements for developers that will have an important impact on the Universal Windows Platform. The major ones are:

- XAML Standard 1.0: as we’re going to learn in detail in the next chapter, XAML is the markup language that is used by the Universal Windows Platform application to design the user interface. However, at the time of writing, the features and the syntax of this language are a bit fragmented across the various Microsoft technologies. For example, another important Microsoft platform that uses this language is Xamarin Forms, which is a technology that developers can use to write cross-platfrom applications (for Windows, Android and iOS), sharing the same user interface and code. However, currently, the two platforms, despite they are both based on XAML, have some naming differences in the syntax, making not possible to reuse the same code moving from one technology to the other.

- .NET Standard Libraries 2.0: .NET Standard Libraries are the evolution of the Portable Class Libraries, and they implement a subset of .NET ecosystem (typically, the parts that are independent from the platform), allowing developers to share the same library (like a backend library to interact with a cloud service) across multiple Microsoft platforms. The version 2.0 of this technology will add support for the Universal Windows Platform, allowing developers to share parts of the code of the Windows 10 application with an Android application built with Xamarin, with a website running on Linux developed with ASP.NET Core or with a classic desktop application for Windows created with WPF.

- 70+ advanced UWP components for Windows Store apps.

- UI controls for LOB apps: Charts, DataGrid, Diagram, and more.

- Comprehensive features for building touch-friendly, Windows 10-style applications.