CHAPTER 4

The SVM Optimization Problem

SVMs search for the optimal hyperplane

The Perceptron has several advantages: it is a simple model, the algorithm is very easy to implement, and we have a theoretical proof that it will find a hyperplane that separates the data. However, its biggest weakness is that it will not find the same hyperplane every time. Why do we care? Because not all separating hyperplanes are equals. If the Perceptron gives you a hyperplane that is very close to all the data points from one class, you have a right to believe that it will generalize poorly when given new data.

SVMs do not have this problem. Indeed, instead of looking for a hyperplane, SVMs tries to find the hyperplane. We will call this the optimal hyperplane, and we will say that it is the one that best separates the data.

How can we compare two hyperplanes?

Because we cannot choose the optimal hyperplane based on our feelings, we need some sort of metric that will allow us to compare two hyperplanes and say which one is superior to all others.

In this section, we will try to discover how we can compare two hyperplanes. In other words, we will search for a way to compute a number that allows us to tell which hyperplane separates the data the best. We will look at methods that seem to work, but then we will see why they do not work and how we can correct their limitations. Let us try with a simple attempt to compare two hyperplanes using only the equation of the hyperplane.

Using the equation of the hyperplane

Given an example ![]() and a hyperplane, we wish to know how the example relates to the hyperplane.

and a hyperplane, we wish to know how the example relates to the hyperplane.

One key element we already know is that if the value of ![]() satisfies the equation of a line, then it means it is on the line. It works in the same way for a hyperplane: for a data point

satisfies the equation of a line, then it means it is on the line. It works in the same way for a hyperplane: for a data point ![]() and a hyperplane defined by a vector

and a hyperplane defined by a vector ![]() and bias

and bias ![]() , we will get

, we will get ![]() if

if ![]() is on the hyperplane.

is on the hyperplane.

But what if the point is not on the hyperplane?

Let us see what happens with an example. In Figure 22, the line is defined by ![]() and

and ![]() . When we use the equation of the hyperplane:

. When we use the equation of the hyperplane:

- for point

![%FontSize=11

%TeXFontSize=11

\documentclass{article}

\pagestyle{empty}

\begin{document}

\[

A(1,3)

\]

\end{document}](https://s3.amazonaws.com/ebooks.syncfusion.com/LiveReadOnlineFiles/support_vector_machines_succinctly/Images/Images\267.png) , using vector

, using vector ![%FontSize=11

%TeXFontSize=11

\documentclass{article}

\pagestyle{empty}

\begin{document}

\[

\mathbf a=(1,3)

\]

\end{document}](https://s3.amazonaws.com/ebooks.syncfusion.com/LiveReadOnlineFiles/support_vector_machines_succinctly/Images/Images\268.png) we get

we get ![%FontSize=11

%TeXFontSize=11

\documentclass{article}

\pagestyle{empty}

\begin{document}

\[

\mathbf w \cdot \mathbf a + b = 5.6

\]

\end{document}](https://s3.amazonaws.com/ebooks.syncfusion.com/LiveReadOnlineFiles/support_vector_machines_succinctly/Images/Images\269.png)

- for point

![%FontSize=11

%TeXFontSize=11

\documentclass{article}

\pagestyle{empty}

\begin{document}

\[

B(3,5)

\]

\end{document}](https://s3.amazonaws.com/ebooks.syncfusion.com/LiveReadOnlineFiles/support_vector_machines_succinctly/Images/Images\270.png) , using vector

, using vector ![%FontSize=11

%TeXFontSize=11

\documentclass{article}

\pagestyle{empty}

\begin{document}

\[

\mathbf b=(3,5)

\]

\end{document}](https://s3.amazonaws.com/ebooks.syncfusion.com/LiveReadOnlineFiles/support_vector_machines_succinctly/Images/Images\271.png) we get

we get ![%FontSize=11

%TeXFontSize=11

\documentclass{article}

\pagestyle{empty}

\begin{document}

\[

\mathbf w \cdot \mathbf b + b = 2.8

\]

\end{document}](https://s3.amazonaws.com/ebooks.syncfusion.com/LiveReadOnlineFiles/support_vector_machines_succinctly/Images/Images\272.png)

- for point

![%FontSize=11

%TeXFontSize=11

\documentclass{article}

\pagestyle{empty}

\begin{document}

\[

C(5,7)

\]

\end{document}](https://s3.amazonaws.com/ebooks.syncfusion.com/LiveReadOnlineFiles/support_vector_machines_succinctly/Images/Images\273.png) , using vector

, using vector ![%FontSize=11

%TeXFontSize=11

\documentclass{article}

\pagestyle{empty}

\begin{document}

\[

\mathbf c=(5,7)

\]

\end{document}](https://s3.amazonaws.com/ebooks.syncfusion.com/LiveReadOnlineFiles/support_vector_machines_succinctly/Images/Images\274.png) we get

we get ![%FontSize=11

%TeXFontSize=11

\documentclass{article}

\pagestyle{empty}

\begin{document}

\[

\mathbf w \cdot \mathbf c + b = 0

\]

\end{document}](https://s3.amazonaws.com/ebooks.syncfusion.com/LiveReadOnlineFiles/support_vector_machines_succinctly/Images/Images\275.png)

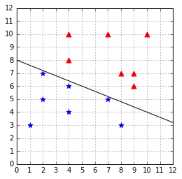

Figure 22: The equation returns a bigger number for A than for B

As you can see, when the point is not on the hyperplane we get a number different from zero. In fact, if we use a point far away from the hyperplane, we will get a bigger number than if we use a point closer to the hyperplane.

Another thing to notice is that the sign of the number returned by the equation tells us where the point stands with respect to the line. Using the equation of the line displayed in Figure 23, we get:

![%FontSize=11

%TeXFontSize=11

\documentclass{article}

\pagestyle{empty}

\begin{document}

\[

2.8

\]

\end{document}](https://s3.amazonaws.com/ebooks.syncfusion.com/LiveReadOnlineFiles/support_vector_machines_succinctly/Images/Images\277.png) for point

for point ![%FontSize=11

%TeXFontSize=11

\documentclass{article}

\pagestyle{empty}

\begin{document}

\[

A(3,5)

\]

\end{document}](https://s3.amazonaws.com/ebooks.syncfusion.com/LiveReadOnlineFiles/support_vector_machines_succinctly/Images/Images\278.png)

![%FontSize=11

%TeXFontSize=11

\documentclass{article}

\pagestyle{empty}

\begin{document}

\[

0

\]

\end{document}](https://s3.amazonaws.com/ebooks.syncfusion.com/LiveReadOnlineFiles/support_vector_machines_succinctly/Images/Images\279.png) for point

for point ![%FontSize=11

%TeXFontSize=11

\documentclass{article}

\pagestyle{empty}

\begin{document}

\[

B(5,7)

\]

\end{document}](https://s3.amazonaws.com/ebooks.syncfusion.com/LiveReadOnlineFiles/support_vector_machines_succinctly/Images/Images\280.png)

![%FontSize=11

%TeXFontSize=11

\documentclass{article}

\pagestyle{empty}

\begin{document}

\[

-2.8

\]

\end{document}](https://s3.amazonaws.com/ebooks.syncfusion.com/LiveReadOnlineFiles/support_vector_machines_succinctly/Images/Images\281.png) for point

for point ![%FontSize=11

%TeXFontSize=11

\documentclass{article}

\pagestyle{empty}

\begin{document}

\[

C(7,9)

\]

\end{document}](https://s3.amazonaws.com/ebooks.syncfusion.com/LiveReadOnlineFiles/support_vector_machines_succinctly/Images/Images\282.png)

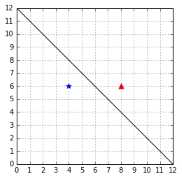

Figure 23: The equation returns a negative number for C

If the equation returns a positive number, the point is below the line, while if it is a negative number, it is above. Note that it is not necessarily visually above or below, because if you have a line like the one in Figure 24, it will be left or right, but the same logic applies. The sign of the number returned by the equation of the hyperplane allows us to tell if two points lie on the same side. In fact, this is exactly what the hypothesis function we defined in Chapter 2 does.

Figure 24: A line can separate the space in different ways

We now have the beginning of a solution for comparing two hyperplanes.

Given a training example ![]() and a hyperplane defined by a vector

and a hyperplane defined by a vector ![]() and bias

and bias ![]() , we compute the number

, we compute the number ![]() to know how far the point is from the hyperplane.

to know how far the point is from the hyperplane.

Given a data set ![]() , we compute

, we compute ![]() for each training example, and say that the number

for each training example, and say that the number ![]() is the smallest

is the smallest ![]() we encounter.

we encounter.

![]()

If we need to choose between two hyperplanes, we will then select the one from which ![]() is the largest.

is the largest.

To be clear, this means that if we have ![]() hyperplanes, we will compute

hyperplanes, we will compute ![]() and select the hyperplane having this

and select the hyperplane having this ![]() .

.

Problem with examples on the negative side

Unfortunately, using the result of the hyperplane equation has its limitations. The problem is that taking the minimum value does not work for examples on the negative side (the ones for which the equation returns a negative value).

Remember that we always wish to take the ![]() of the point being the closest to the hyperplane. Computing

of the point being the closest to the hyperplane. Computing ![]() with examples on the positive side actually does this. Between two points with

with examples on the positive side actually does this. Between two points with ![]() and

and ![]() , we pick the one having the smallest number, so we choose

, we pick the one having the smallest number, so we choose ![]() . However, between two examples having

. However, between two examples having ![]() and

and ![]() , this rule will pick

, this rule will pick ![]() because

because ![]() is smaller than

is smaller than ![]() , but the closest point is actually the one with

, but the closest point is actually the one with ![]() .

.

One way to fix this problem is to consider the absolute value of ![]() .

.

Given a data set ![]() , we compute

, we compute ![]() for each example and say that

for each example and say that ![]() is the

is the ![]() having the smallest absolute value:

having the smallest absolute value:

![]()

Does the hyperplane correctly classify the data?

Computing the number ![]() allows us to select a hyperplane. However, using only this value, we might pick the wrong one. Consider the case in Figure 25: the examples are correctly classified, and the value of

allows us to select a hyperplane. However, using only this value, we might pick the wrong one. Consider the case in Figure 25: the examples are correctly classified, and the value of ![]() computed using the last formula is 2.

computed using the last formula is 2.

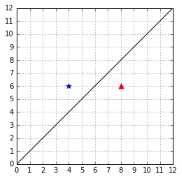

Figure 25: A hyperplane correctly classifying the data

In Figure 26, the examples are incorrectly classified, and the value of ![]() is also 2. This is problematic because using

is also 2. This is problematic because using ![]() , we do not know which hyperplane is better. In theory, they look equally good, but in reality, we want to pick the one from Figure 25.

, we do not know which hyperplane is better. In theory, they look equally good, but in reality, we want to pick the one from Figure 25.

Figure 26: A hyperplane that does not classify the data correctly

How can we adjust our formula to meet this requirement?

Well, there is one component of our training example ![]() that we did not use: the

that we did not use: the ![]() !

!

If we multiply ![]() by the value of

by the value of ![]() , we change its sign. Let us call this new number

, we change its sign. Let us call this new number ![]() :

:

![]()

![]()

The sign of ![]() will always be:

will always be:

- Positive if the point is correctly classified

- Negative if the point is incorrectly classified

Given a data set ![]() , we can compute:

, we can compute:

![]()

![]()

With this formula, when comparing two hyperplanes, we will still select the one for which ![]() is the largest. The added bonus is that in special cases like the ones in Figure 25 and Figure 26, we will always pick the hyperplane that classifies correctly (because

is the largest. The added bonus is that in special cases like the ones in Figure 25 and Figure 26, we will always pick the hyperplane that classifies correctly (because ![]() will have a positive value, while its value will be negative for the other hyperplane).

will have a positive value, while its value will be negative for the other hyperplane).

In the literature, the number ![]() has a name, it is called the functional margin of an example; its value can be computed in Python, as shown in Code Listing 19. Similarly, the number

has a name, it is called the functional margin of an example; its value can be computed in Python, as shown in Code Listing 19. Similarly, the number ![]() is known as the functional margin of the data set

is known as the functional margin of the data set ![]() .

.

# Compute the functional margin of an example (x,y) |

Using this formula, we find that the functional margin of the hyperplane in Figure 25 is +2, while in Figure 26 it is -2. Because it has a bigger margin, we will select the first one.

Tip: Remember, we wish to choose the hyperplane with the largest margin.

Scale invariance

It looks like we found a good way to compare the two hyperplanes this time. However, there is a major problem with the functional margin: is not scale invariant.

Given a vector ![]() and bias

and bias ![]() , if we multiply them by 10, we get

, if we multiply them by 10, we get ![]() and

and ![]() . We say we rescaled them.

. We say we rescaled them.

The vectors ![]() and

and ![]() , represent the same hyperplane because they have the same unit vector. The hyperplane being a plane orthogonal to a vector

, represent the same hyperplane because they have the same unit vector. The hyperplane being a plane orthogonal to a vector ![]() , it does not matter how long the vector is. The only thing that matters is its direction, which, as we saw in the first chapter, is given by its unit vector. Moreover, when tracing the hyperplane on a graph, the coordinate of the intersection between the vertical axis and the hyperplane will be

, it does not matter how long the vector is. The only thing that matters is its direction, which, as we saw in the first chapter, is given by its unit vector. Moreover, when tracing the hyperplane on a graph, the coordinate of the intersection between the vertical axis and the hyperplane will be ![]() , so the hyperplane does not change because of the rescaling of

, so the hyperplane does not change because of the rescaling of ![]() , either.

, either.

The problem, as we can see in Code Listing 20, is that when we compute the functional margin with ![]() , we get a number ten times bigger than with

, we get a number ten times bigger than with ![]() . This means that given any hyperplane, we can always find one that will have a larger functional margin, just by rescaling

. This means that given any hyperplane, we can always find one that will have a larger functional margin, just by rescaling ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

x = np.array([1, 1]) |

To solve this problem, we only need to make a small adjustment. Instead of using the vector ![]() , we will use its unit vector. To do so, we will divide

, we will use its unit vector. To do so, we will divide ![]() by its norm. In the same way, we will divide

by its norm. In the same way, we will divide ![]() by the norm of

by the norm of ![]() to make it scale invariant as well.

to make it scale invariant as well.

Recall the formula of the functional margin: ![]()

We modify it and obtain a new number ![]() :

:

![]()

As before, given a data set ![]() , we can compute:

, we can compute:

![]()

![]()

The advantage of ![]() is that it gives us the same number no matter how large is the vector

is that it gives us the same number no matter how large is the vector ![]() that we choose. The number

that we choose. The number ![]() also has a name—it is called the geometric margin of a training example, while

also has a name—it is called the geometric margin of a training example, while ![]() is the geometric margin of the dataset. A Python implementation is shown in Code Listing 21.

is the geometric margin of the dataset. A Python implementation is shown in Code Listing 21.

# Compute the geometric margin of an example (x,y) |

We can verify that the geometric margin behaves as expected. In Code Listing 22, the function returns the same value for the vector ![]() or its rescaled version

or its rescaled version ![]() .

.

x = np.array([1,1]) |

It is called the geometric margin because we can retrieve this formula using simple geometry. It measures the distance between ![]() and the hyperplane.

and the hyperplane.

In Figure 27, we see that the point ![]() is the orthogonal projection of

is the orthogonal projection of ![]() into the hyperplane. We wish to find the distance

into the hyperplane. We wish to find the distance ![]() between

between ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

Figure 27: The geometric margin is the distance d between the point X and the hyperplane

The vector ![]() has the same direction as the vector

has the same direction as the vector ![]() , so they share the same unit vector

, so they share the same unit vector ![]() . We know that the norm of

. We know that the norm of ![]() is

is ![]() , so the vector

, so the vector ![]() can be defined by

can be defined by ![]() .

.

Moreover, we can see that ![]() , so if we substitute for

, so if we substitute for ![]() and do a little bit of algebra, we get:

and do a little bit of algebra, we get:

![]()

Now, the point ![]() is on the hyperplane. It means that

is on the hyperplane. It means that ![]() satisfies the equation of the hyperplane, and we have:

satisfies the equation of the hyperplane, and we have:

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Eventually, as we did before, we multiply by ![]() to ensure that we select a hyperplane that correctly classifies the data, and it gives us the geometric margin formula we saw earlier:

to ensure that we select a hyperplane that correctly classifies the data, and it gives us the geometric margin formula we saw earlier:

![]()

|

|

Now that we have defined the geometric margin, let us see how it allows us to compare two hyperplanes. We can see that the hyperplane in Figure 28 is closer to the blue star examples than to the red triangle examples as compared to the one in Figure 29. As a result, we expect its geometric margin to be smaller. Code Listing 23 uses the function defined in Code Listing 21 to compute the geometric margin for each hyperplane. As expected from Figure 29, the geometric margin of the second hyperplane defined by ![]() and

and ![]() is larger (0.64 > 0.18). Between the two, we would select this hyperplane.

is larger (0.64 > 0.18). Between the two, we would select this hyperplane.

# Compare two hyperplanes using the geometrical margin. |

We see that to compute the geometric margin for another hyperplane, we just need to modify the value of ![]()

![]() or

or ![]() . We could try to change it by a small increment to see if the margin gets larger, but it is kind of random, and it would take a lot of time. Our objective is to find the optimal hyperplane for a dataset among all possible hyperplanes, and there is an infinity of hyperplanes.

. We could try to change it by a small increment to see if the margin gets larger, but it is kind of random, and it would take a lot of time. Our objective is to find the optimal hyperplane for a dataset among all possible hyperplanes, and there is an infinity of hyperplanes.

Tip: Finding the optimal hyperplane is just a matter of finding the values of w and b for which we get the largest geometric margin.

How can we find the value of ![]() that produces the largest geometric margin? Luckily for us, mathematicians have designed tools to solve such problems. To find

that produces the largest geometric margin? Luckily for us, mathematicians have designed tools to solve such problems. To find ![]() and

and ![]() , we need to solve what is called an optimization problem. Before looking at what the optimization problem is for SVMs, let us do a quick review of what an optimization problem is.

, we need to solve what is called an optimization problem. Before looking at what the optimization problem is for SVMs, let us do a quick review of what an optimization problem is.

What is an optimization problem?

Unconstrained optimization problem

The goal of an optimization problem is to minimize or maximize a function with respect to some variable x (that is, to find the value of x for with the function returns its minimum or maximum value). For instance, the problem in which we want to find the minimum of the function ![]() is written:

is written:

![]()

Or, alternatively:

![]()

In this case, we are free to search amongst all possible values of ![]() . We say that the problem is unconstrained. As we can see in Figure 30, the minimum of the function is zero at

. We say that the problem is unconstrained. As we can see in Figure 30, the minimum of the function is zero at ![]() .

.

Figure 30: Without constraint, the minimum is zero |

Figure 31: Because of the constraint x-2=0, the minimum is 4 |

Constrained optimization problem

Single equality constraint

Sometimes we are not interested in the minimum of the function by itself, but rather its minimum when some constraints are met. In such cases, we write the problem and add the constraints preceded by ![]() , which is often abbreviated

, which is often abbreviated ![]() For instance, if we wish to know the minimum of

For instance, if we wish to know the minimum of ![]() but restrict the value of

but restrict the value of ![]() to a specific value, we can write:

to a specific value, we can write:

![]()

This example is illustrated in Figure 31. In general, constraints are written by keeping zero on the right side of the equality so the problem can be rewritten:

![]()

Using this notation, we clearly see that the constraint is an affine function while the objective function ![]() is a quadratic function. Thus we call this problem a quadratic optimization problem or a Quadratic Programming (QP) problem.

is a quadratic function. Thus we call this problem a quadratic optimization problem or a Quadratic Programming (QP) problem.

Feasible set

The set of variables that satisfies the problem constraints is called the feasible set (or feasible region). When solving the optimization problem, the solution will be picked from the feasible set. In Figure 31, the feasible set contains only one value, so the problem is trivial. However, when we manipulate functions with several variables, such as ![]() , it allows us to know from which values we are trying to pick a minimum (or maximum).

, it allows us to know from which values we are trying to pick a minimum (or maximum).

For example:

![]()

In this problem, the feasible set is the set of all pairs of points ![]() , such as

, such as ![]() .

.

Multiple equality constraints and vector notation

We can add as many constraints as we want. Here is an example of a problem with three constraints for the function ![]() :

:

When we have several variables, we can switch to vector notation to improve readability. For the vector ![]() the function becomes

the function becomes ![]() , and the problem is written:

, and the problem is written:

When adding constraints, keep in mind that doing so reduces the feasible set. For a solution to be accepted, all constraints must be satisfied.

For instance, let us look at the following the problem:

We could think that ![]() and

and ![]() are solutions, but this is not the case. When

are solutions, but this is not the case. When ![]() , the constraint

, the constraint ![]() is not met; and when

is not met; and when ![]() , the constraint

, the constraint ![]() is not met. The problem is infeasible.

is not met. The problem is infeasible.

Tip: If you add too many constraints to a problem, it can become infeasible.

If you change an optimization problem by adding a constraint, you make the optimum worse, or, at best, you leave it unchanged (Gershwin, 2010).

Inequality constraints

We can also use inequalities as constraints:

And we can combine equality constraints and inequality constraints:

How do we solve an optimization problem?

Several methods exist that can solve each type of optimization problem. However, presenting them is outside the scope of this book. The interested reader can see Optimization Models and Application (El Ghaoui, 2015) and Convex Optimization (Boyd & Vandenberghe, 2004), two good books for starting on the subject and that are available online for free (see Bibliography for details). We will instead focus on the SVMs again and derive an optimization problem allowing us to find the optimal hyperplane. How to solve the SVMs optimization problem will be explained in detail in the next chapter.

The SVMs optimization problem

Given a linearly separable training set ![]() and a hyperplane with a normal vector

and a hyperplane with a normal vector ![]() and bias

and bias ![]() , recall that the geometric margin

, recall that the geometric margin ![]() of the hyperplane is defined by:

of the hyperplane is defined by:

![]()

where ![]() is the geometric margin of a training example

is the geometric margin of a training example ![]() .

.

The optimal separating hyperplane is the hyperplane defined by the normal vector ![]() and bias

and bias ![]() for which the geometric margin

for which the geometric margin ![]() is the largest.

is the largest.

To find ![]() and

and ![]() , we need to solve the following optimization problem, with the constraint that the margin of each example should be greater or equal to

, we need to solve the following optimization problem, with the constraint that the margin of each example should be greater or equal to ![]() :

:

![]()

There is a relationship between the geometric margin and the functional margin:

![]()

So we can rewrite the problem:

We can then simplify the constraint by removing the norm on both sides of the inequality:

![]()

Recall that we are trying to maximize the geometric margin and that the scale of ![]() and

and ![]() does not matter. We can choose to rescale

does not matter. We can choose to rescale ![]() and

and ![]() as we want, and the geometric margin will not change. As a result, we decide to scale

as we want, and the geometric margin will not change. As a result, we decide to scale ![]() and

and ![]() so that

so that ![]() . It will not affect the result of the optimization problem.

. It will not affect the result of the optimization problem.

The problem becomes:

![]()

Because ![]() it is the same as:

it is the same as:

And because we decided to set ![]() , this is equivalent to:

, this is equivalent to:

This maximization problem is equivalent to the following minimization problem:

![]()

Tip: You can also read an alternate derivation of this optimization problem on this page, where I use geometry instead of the functional and geometric margins.

This minimization problem gives the same result as the following:

The factor ![]() has been added for later convenience, when we will use QP solver to solve the problem and squaring the norm has the advantage of removing the square root.

has been added for later convenience, when we will use QP solver to solve the problem and squaring the norm has the advantage of removing the square root.

Eventually, here is the optimization problem as you will see it written in most of the literature:

Why did we take the pain of rewriting the problem like this? Because the original optimization problem was difficult to solve. Instead, we now have convex quadratic optimization problem, which, although not obvious, is much simpler to solve.

Summary

First, we assumed that some hyperplanes are better than others: they will perform better with unseen data. Among all possible hyperplanes, we decided to call the “best” hyperplane the optimal hyperplane. To find the optimal hyperplane, we searched for a way to compare two hyperplanes, and we ended up with a number allowing us to do so. We realized that this number also has a geometrical meaning and is called the geometric margin.

We then stated that the optimal hyperplane is the one with the largest geometric margin and that we can find it by maximizing the margin. To make things easier, we noted that we could minimize the norm of ![]() , the vector normal to the hyperplane, and we will be sure that it will be the

, the vector normal to the hyperplane, and we will be sure that it will be the ![]() of the optimal hyperplane (because if you recall,

of the optimal hyperplane (because if you recall, ![]() is used in the formula for computing the geometric margin).

is used in the formula for computing the geometric margin).

- 1800+ high-performance UI components.

- Includes popular controls such as Grid, Chart, Scheduler, and more.

- 24x5 unlimited support by developers.