CHAPTER 9

Multi-Class SVMs

SVMs are able to generate binary classifiers. However, we are often faced with datasets having more than two classes. For instance, the original wine dataset actually contains data from three different producers. There are several approaches that allow SVMs to work for multi-class classification. In this chapter, we will review some of the most popular multi-class methods and explain where they come from.

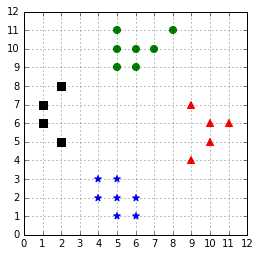

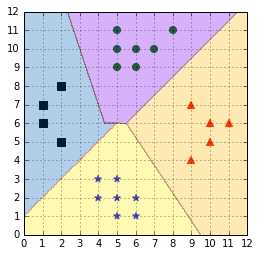

For all code examples in this chapter, we will use the dataset generated by Code Listing 41 and displayed in Figure 51.

import numpy as np |

Figure 51: A four classes classification problem

Solving multiple binary problems

One-against-all

Also called “one-versus-the-rest,” this is probably the simplest approach.

In order to classify K classes, we construct K different binary classifiers. For a given class, the positive examples are all the points in the class, and the negative examples are all the points not in the class (Code Listing 42).

import numpy as np # Create a simple dataset X = load_X()

# in 4 binary classes problems. |

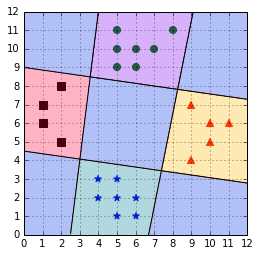

We train one binary classifier on each problem (Code Listing 43). As a result, we obtain one decision boundary per classifier (in Figure 52).

# Train one binary classifier on each problem. classifiers = [] |

Figure 52: The One-against-all approach creates one classifier per class

In order to make a new prediction, we use each classifier and predict the class of the classifier if it returns a positive answer (Code Listing 44). However, this can give inconsistent results because a label is assigned to multiple classes simultaneously or to none (Bishop, 2006). Figure illustrates this problem; the one-against-all classifier is not able to predict a class for the examples in the blue areas in each corner because two classifiers are making a positive prediction. This would result in the example having two class simultaneously. The same problem occurs in the center because each classifier makes a negative prediction. As a result, no class can be assigned to an example in this region.

def predict_class(X, classifiers): |

Figure 53: One-against-all leads to ambiguous decisions

As an alternative solution, Vladimir Vapnik suggested using the class of the classifier for which the value of the decision function is the maximum (Vapnik V. N., 1998). This is demonstrated in Code Listing 45. Note that we use the decision_function instead of calling the predict method of the classifier. This method returns a real value that will be positive if the example is on the correct side of the classifier, and negative if it is on the other side. It is interesting to note that by taking the maximum of the value, and not the maximum of the absolute value, this approach will choose the class of the hyperplane the closest to the example when all classifiers disagree. For instance, the example point (6,4) in Figure will be assigned the blue star class.

def predict_class(X, classifiers): # return the argmax of the decision function as suggested by Vapnik. |

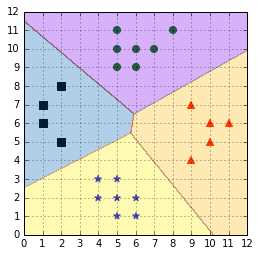

Applying this heuristic gives us classification results with no ambiguity, as shown in Figure . The major flaw of this approach is that the different classifiers were trained on different tasks, so there is no guarantee that the quantities returned by the decision_function have the same scale (Bishop, 2006). If one decision function returns a result ten times bigger than results of the others, its class will be assigned incorrectly to some examples.

Figure 54: Applying a simple heuristic avoids the ambiguous decision problem

Another issue with the one-against-all approach is that training sets are imbalanced (Bishop, 2006). For a problem with 100 classes, each having 10 examples, each classifier will be trained with 10 positive examples and 990 negative examples. Thus, the negative examples will influence the decision boundary greatly.

Nevertheless, one-against-all remains a popular method for multi-class classification because it is easy to implement and understand.

Note: “[...] In practice the one-versus-the-rest approach is the most widely used in spite of its ad-hoc formulation and its practical limitations.” (Bishop, 2006)

When using sklearn, LinearSVC automatically uses the one-against-all strategy by default. You can also specify it explicitly by setting the multi_class parameter to ovr (one-vs-the-rest), as shown in Code Listing 46.

from sklearn.svm import LinearSVC |

One-against-one

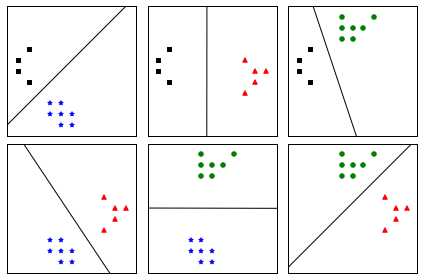

In this approach, instead of trying to distinguish one class from all the others, we seek to distinguish one class from another one. As a result, we train one classifier per pair of classes, which leads to K(K-1)/2 classifiers for K classes. Each classifier is trained on a subset of the data and produces its own decision boundary (Figure ).

Predictions are made using a simple voting strategy. Each example we wish to predict is passed to each classifier, and the predicted class is recorded. Then, the class having the most votes is assigned to the example (Code Listing 47).

from itertools import combinations from scipy.stats import mode import numpy as np # Predict the class having the max number of votes. class_pair[0], class_pair[1]) # prints [2 1] |

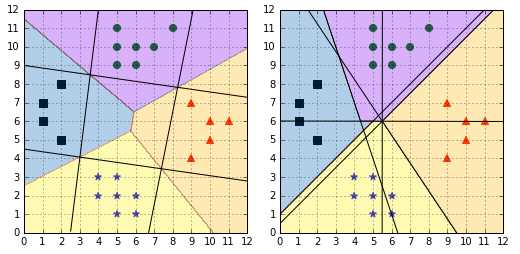

Figure 55: One-against-one construct with one classifier for each pair of classes

With this approach, we are still faced with the ambiguous classification problem. If two classes have an identical number of votes, it has been suggested that selecting the one with the smaller index might be a viable (while probably not the best) strategy (Hsu & Lin, A Comparison of Methods for Multi-class Support Vector Machines, 2002).

Figure 56: Predictions are made using a voting scheme

Figure shows us that the decision regions generated by the one-against-one strategy are different from the ones generated by one-against-all (Figure ). In Figure , it is interesting to note that for regions generated by the one-against-one classifier, a region changes its color only after traversing a hyperplane (denoted by black lines), while this is not the case with one-against-all.

Figure 57: Comparison of one-against-all (left) and one-against-one (right)

The one-against-one approach is the default approach for multi-class classification used in sklearn. Instead of Code Listing 47, you will obtain the exact same results using the code of Code Listing 48.

from sklearn import svm |

One of the main drawbacks of the one-against-all method is that the classifier will tend to overfit.

Moreover, the size of the classifier grows super-linearly with the number of classes, so this method will be slow for large problems (Platt, Cristianini, & Shawe-Taylor, 2000).

DAGSVM

DAGSVM stands for “Directed Acyclic Graph SVM.” It has been proposed by John Platt et al. in 2000 as an improvement of one-against-one (Platt, Cristianini, & Shawe-Taylor, 2000).

Note: John C. Platt invented the SMO algorithm and Platt Scaling, and proposed the DAGSVM. Quite a contribution to the SVMs world!

The idea behind DAGSVM is to use the same training as one-against-one, but to speed up testing by using a directed acyclic graph (DAG) to choose which classifiers to use.

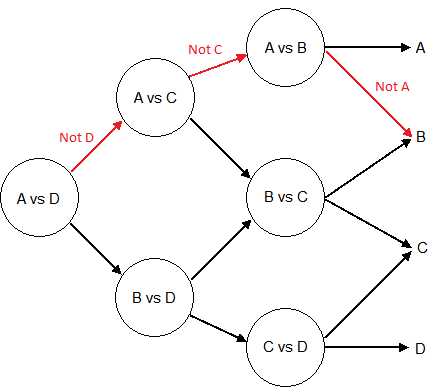

If we have four classes A, B, C, and D, and six classifiers trained each on a pair of classes: (A, B); (A, C); (A, D); (B, C); (B, D); and (C, D). We use the first classifier, (A, D), and it predicts class A, which is the same as predicting not class D, and the second classifier also predits class A (not class C). It means that classifiers (B, D), (B, C) or (C, D) can be ignored because we already know the class is neither C nor D. The last “useful” classifier is (A, B), and if it predicts B, we assign the class B to the data-point. This example is illustrated with the red path in Figure . Each node of the graph is a classifier for a pair of class.

Figure 58: Illustration of the path used to make a prediction along a Directed Acyclic graph

With four classes, we used three classifiers to make the prediction, instead of six with one-against-one. In general, for a problem with K classes, K-1 decision nodes will be evaluated.

Substituting the predict_class function in Code Listing 47 with the one in Code Listing 49 gives the same result, but with the benefit of using fewer classifiers.

In Code Listing 49, we implement the DAGSVM approach with a list. We begin with the list of possible classes, and after each prediction, we remove the one that has been disqualified. In the end, the remaining class is the one which should be assigned to the example.

Note that Code Listing 49 is here for illustration purposes and should not be used in your production code, as it is not fast when the dataset (X) is large.

def predict_class(X, classifiers, distinct_classes, class_pairs): # last element in the list. |

Note: “The DAGSVM is between a factor 1.6 and 2.3 times faster to evaluate than Max Wins.” (Platt, Cristianini, & Shawe-Taylor, 2000).

Solving a single optimization problem

Instead of trying to solve several binary optimization problems, another approach is to try to solve a single optimization problem. This approach has been proposed by several people over the years.

Vapnik, Weston, and Watkins

This method is a generalization of the SVMs optimization problem to solve the multi-class classification problem directly. It has been independently discovered by Vapnik (Vapnik V. N., 1998) and Weston & Watkins (Weston & Watkins, 1999). For every class, constraints are added to the optimization problem. As a result, the size of the problem is proportional to the number of classes and can be very slow to train.

Crammer and Singer

Crammer and Singer (C&S) proposed an alternative approach to multi-class SVMs. Like Weston and Watkins, they solve a single optimization problem, but with fewer slack variables (Crammer & Singer, 2001). This has the benefit of reducing the memory and training time. However, in their comparative study, Hsu & Lin found that the C&S method was especially slow when using a large value for the C regularization parameter (Hsu & Lin, A Comparison of Methods for Multi-class Support Vector Machines, 2002).

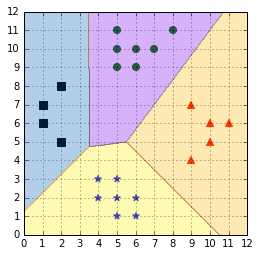

In sklearn, when using LinearSVC you can choose to use the C&S algorithm (Code Listing 50). In Figure , we can see that the C&S predictions are different from the one-against-all and the one-against-one methods.

from sklearn import svm |

Figure 59: Crammer & Singer algorithm predictions

Which approach should you use?

With so many options available, choosing which multi-class approach is better suited for your problem can be difficult.

Hsu and Lin wrote an interesting paper comparing the different multi-class approaches available for SVMs (Hsu & Lin, A Comparison of Methods for Multi-class Support Vector Machines, 2002). They conclude that “the one-against-one and DAG methods are more suitable for practical use than the other methods.” The one-against-one method has the added advantage of being already available in sklearn, so it should probably be your default choice.

Be sure to remember that LinearSVC uses the one-against-all method by default, and that maybe using the Crammer & Singer algorithm will better help you achieve your goal. On this topic, Dogan et al. found that despite being considerably faster than other algorithms, one-against-all yield hypotheses with a statistically significantly worse accuracy (Dogan, Glasmachers, & Igel, 2011). Table 1 provides an overview of the methods presented in this chapter to help you make a choice.

Table 1: Overview of multi-class SVM methods

Method name | One-against-all | One-against-one | Weston and Watkins | DAGSVM | Crammer and Singer |

First SVMs usage | 1995 | 1996 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 |

Approach | Use several binary classifiers | Use several binary classifiers | Solve a single optimization problem | Use several binary classifiers | Solve a single optimization problem |

Training approach | Train a single classifier for each class | Train a classifier for each pair of classes | Decomposition method | Same as one-against-one | Decomposition method |

Number of trained classifiers ( |

|

| 1 |

| 1 |

Testing approach | Select the class with the biggest decision function value | “Max-Wins” voting strategy | Use the classifier | Use a DAG to make predictions on K-1 classifiers | Use the classifier |

scikit-learn class | LinearSVC | SVC | Not available | Not available | LinearSVC |

Drawbacks | Class imbalance | Long training time for large K | Long training time | Not available in popular libraries | Long training time |

Summary

Thanks to many improvements over the years, there are now several methods for doing multi-class classification with SVMs. Each approach has advantages and drawbacks, and most of the time you will end up using the one available in the library you are using. However, if necessary, you now know which method can be more helpful to solve your specific problem.

Research on multi-class SVMs is not over. Recent papers on the subject have been focused on distributed training. For instance, Han & Berg have presented a new algorithm called “Distributed Consensus Multiclass SVM,” which uses consensus optimization with a modified version of Crammer & Singer’s formulation (Han & Berg, 2012).

- 1800+ high-performance UI components.

- Includes popular controls such as Grid, Chart, Scheduler, and more.

- 24x5 unlimited support by developers.