CHAPTER 5

Selecting From Yourself

In Chapter 2 we stepped through the various options for joining different tables. We looked at how inner joins, outer joins, and cross joins differ. In this chapter we will look at joining tables to themselves.

Joining the same table multiple times

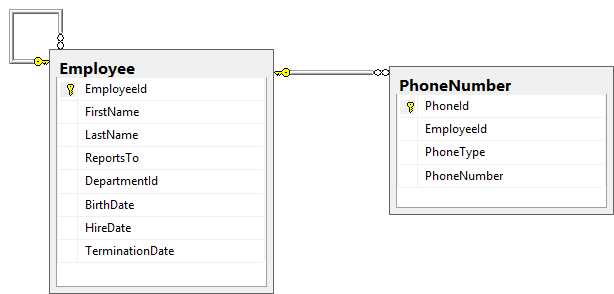

Sometimes with a normalized data model, you will find that you need to join a table multiple times to get full details. Let’s extend the Employee model to track multiple phone numbers. It doesn’t make sense to add a new column for each type of phone number you want to track. Instead, we will add a new table that will have a separate record for each phone number that we want to track. This simplifies adding new types of phone numbers, but querying to get all of the phone numbers can be a bit more involved.

Figure 5-1: Data model for employees and their phone numbers

Selecting various phone numbers

This data model is a good design, and is commonly implemented, but is not without its problems. Our initial attempt to retrieve the home phone number for all employees might look like this:

Code Listing 5-1: Initial join between Employee and PhoneNumber

SELECT Employee.EmployeeId , FirstName , LastName , PhoneType , PhoneNumber FROM dbo.Employee JOIN dbo.PhoneNumber ON PhoneNumber.EmployeeId = Employee.EmployeeId WHERE PhoneType = 4 ORDER BY LastName , FirstName |

Looking through the result set, we can quickly see the problems with this query. As an inner join, employees without a home phone are missing. The other problem is that this data model allows multiple home phone numbers.

Tip: To ensure that an employee does not have duplicate PhoneTypes, you could add a unique constraint on the EmployeeId, PhoneType combination. However, if you already have many duplicates, this may not be an option.

Resolving the first issue is straightforward: convert the inner join to an outer join.

Code Listing 5-2: Outer join between the Employee and PhoneNumber Tables

SELECT Employee.EmployeeId , FirstName , LastName , PhoneType , PhoneNumber FROM dbo.Employee LEFT OUTER JOIN dbo.PhoneNumber ON PhoneNumber.EmployeeId = Employee.EmployeeId AND PhoneType = 4 ORDER BY LastName , FirstName |

Note: We have to also move the PhoneType check from the WHERE clause to the JOIN clause for it to be included as an outer join condition.

Eliminating the redundant phone numbers is a bit more challenging. We want to get a single record for each EmployeeId. This is where a TOP expression can be useful. With this expression, we can explicitly specify how many records should be returned in the result set. We want to ensure that there is only a single matching record pulled from the PhoneNumber table.

For this to work, we need a correlated subquery. This means that the subquery will reference data contained in the outer query. This also means that the subquery will be executed once for every record from the containing query. Otherwise the TOP expression would not make sense, and would always return only a single row. This also means that we’ll need a new type of JOIN logic to join to this subquery.

Code Listing 5-3: Joining Employee and PhoneNumber tables with a CROSS APPLY

SELECT Employee.EmployeeId , FirstName , LastName , PhoneType , PhoneNumber FROM dbo.Employee CROSS APPLY ( SELECT TOP 1 PhoneNumber , PhoneType , EmployeeId FROM dbo.PhoneNumber WHERE PhoneType = 4 AND EmployeeId = Employee.EmployeeId ) p ORDER BY EmployeeId; |

Note: Anytime you have a subquery like the one in Code Listing 5-3, you must give it an alias so that you can refer to it at other places in the query. In this case, you won’t have to refer to it later, but you still must provide an alias; in this case, p.

CROSS APPLY is similar to the CROSS JOIN that we used earlier to create a Cartesian product, except we know that we will have only a single record in the second table. This is not exactly what we want either, because any Employee records that have no PhoneNumber would be excluded from the list. Fortunately, the CROSS APPLY has a partner operation called the OUTER APPLY, which will allow us to show every record exept the ones missing data from the correlated subquery. Just like outer joins, the missing data will be replaced with NULL values or whatever value is specified as a default for that column.

So our final query to get the Employee records along with an associated home phumber, if they have one, is:

Code Listing 5-4: Joining the Employee and PhoneNumber tables with an OUTER APPLY

SELECT Employee.EmployeeId , FirstName , LastName , PhoneType , PhoneNumber FROM dbo.Employee OUTER APPLY ( SELECT TOP 1 PhoneNumber , PhoneType , EmployeeId FROM dbo.PhoneNumber WHERE PhoneType = 4 AND EmployeeId = Employee.EmployeeId ) p ORDER BY EmployeeId; |

Not too bad, but a query that needs to show an Employee record along with any home phone number information may also want to include other phone numbers, such as the cell phone, office phone, fax number, etc. Adding a correlated subquery for each of these types will add a lot of complexity to the final query and make it harder to follow.

This is where a table-valued function can be used. A table-valued function allows us to create a parameterized view or common table expression and returns a Result Set, or in this case, a single record. This means that it can be used anywhere that a table could be used, included as a correlated subquery.

Note: Even though our table-valued function will return a single record, it is still returning a Result Set.

Our table-valued function is easy to define because it looks a lot like our correlated subquery:

Code Listing 5-5: Defining the table-valued function

CREATE FUNCTION EmployeePhoneNumberByType ( @EmployeeId INT , @PhoneType INT ) RETURNS TABLE AS RETURN SELECT TOP 1 PhoneId , EmployeeId , PhoneType , PhoneNumber FROM dbo.PhoneNumber WHERE EmployeeId = @EmployeeId AND PhoneType = @PhoneType; |

It’s also easy to use:

Code Listing 5-6: Using the table-valued function

SELECT Employee.EmployeeId , FirstName , LastName , Home.PhoneNumber AS Home, Office.PhoneNumber AS Office, cell.PhoneNumber AS Cell, fax.PhoneNumber AS Fax FROM dbo.Employee OUTER APPLY dbo.EmployeePhoneNumberByType(Employee.EmployeeId, 4) AS Home OUTER APPLY dbo.EmployeePhoneNumberByType(Employee.EmployeeId, 1) AS Office OUTER APPLY dbo.EmployeePhoneNumberByType(Employee.EmployeeId, 2) AS Cell OUTER APPLY dbo.EmployeePhoneNumberByType(Employee.EmployeeId, 3) AS Fax ORDER BY EmployeeId; |

Depending on the amount of data in your database, you might start seeing a problem with this approach at this point.

Note: Because we are calling this table-valued function in four separate OUTER APPLY statements, we are calling it four times for each record that is returned. As the number of records grows, this can be become very expensive.

If you do not have the volume of data that causes such a performance problem, this query may be all that you need, but if you do encounter performance issues, then we may need to get more creative to optimize this query for performance.

Tip: Don’t optimize away clarity unless you are having a performance problem. A clever solution that is difficult to follow will be difficult to maintain, and could have errors that are hard to detect or resolve.

To optimize away the need to call a correlated subquery (or worse, four correlated subqueries) for each record, we will need a better way to limit ourselves to a single record without having to use the TOP clause. We may have to add a couple of additional subqueries to the mix, but as long as they are not correlated, we will see a nice performance improvement.

Code Listing 5-7: Optimized query eliminating the correlated subquery

SELECT Employee.EmployeeId , FirstName , LastName , PhoneNumber AS HomePhone FROM dbo.Employee LEFT OUTER JOIN ( ( SELECT EmployeeId , MAX(PhoneId) AS PhoneId FROM dbo.PhoneNumber WHERE PhoneType = 4 GROUP BY EmployeeId ) HomePhoneId INNER JOIN dbo.PhoneNumber ON HomePhoneId.PhoneId = PhoneNumber.PhoneId ) ON PhoneNumber.EmployeeId = Employee.EmployeeId; |

In performance testing on my local database loaded with 10,000 Employee records and 6,000 PhoneNumber records, the original query to return a home phone number took an average of 3,421 ms. The optimized version took an average of 48 ms.

This is a substantial improvement. Three seconds to run a query is rarely going to be acceptable, especially when it could be brought back down to a fraction of a second.

Now that we have seen that this optimization does actually produce performance gains, let’s look at the details for how we work such magic.

Let’s start with the nested join in the middle of the query.

Tip: When breaking a query apart, the middle is often the best place to start.

The first part, which we will call HomePhoneId, will give us the PhoneId for the last record with a PhoneType entered for each employee. This will allow us to filter down to a single record for each employee, but it does not give us the PhoneNumber, but rather the primary key to get the full record for that phone number.

Code Listing 5-8: Finding the primary key for the home PhoneNumber for each employee

SELECT EmployeeId , MAX(PhoneId) AS PhoneId FROM dbo.PhoneNumber WHERE PhoneType = 4 GROUP BY EmployeeId |

Viewed by itself, we can see that this is a simple query using the MAX aggregate function and a single GROUP BY. Let’s look at a few of the records returned.

EmployeeId | PhoneId |

|---|---|

1 | 334071 |

2 | 315909 |

3 | 393938 |

4 | 393715 |

5 | 352673 |

6 | 327152 |

7 | 385227 |

8 | 342555 |

9 | 383116 |

10 | 342805 |

Result Set 5-1: Finding the PhoneId for the home phone for each employee

When looking at this result set, we need to remember that there is no guarantee that the result will include a record for each EmployeeId. The MAX aggregate function will reduce multiple records to a single record, but it does not help with employee records with no home phone records.

If there is no record for an EmployeeId in the HomePhoneId subquery, we will not have anything to match against in the PhoneNumber table either. By nesting this join, we are able to deal with the result of the join as a whole outside of the scoping. In this case, we take the result of joining the subquery HomePhoneId with the PhoneNumber table, and then do an outer join to the Employee table. Without the nested join, we would have to do a two-level outer join, which isn’t really possible because the first outer join will fill in the blanks with NULL values, leaving nothing to match against for the second-level join.

The nested join allows us to avoid this problem by treating both joins as one.

General selecting trees and graphs

Trees and graphs are the general names we give to any hierarchical table structures. This is a table that has a foreign key back to itself. As long as there are no cycles in the relationships, we call it a tree. If there are cycles in the relationships, it is a graph.

Both types of data structures have many uses and show up in various scenarios. We have already seen one in the Employee table. It includes a reference back to itself to show who each employee reports to.

Note: A hierarchical table may be used to track all manner of hierarchical data from org charts to sales hierarchies, to operational hierarchies, to nested questions on a questionnaire, or to a bill of materials. Many of these techniques are useful regardless of the purpose of the data stored.

Classic organization chart

Let’s revisit the Employee table, this time paying attention to the ReportsTo column that we have ignored so far.

Figure 5-2: Revisiting the Employee table with the ReportsTo reference

The ReportsTo column forms a foreign key back to the EmployeeId for another record. If it’s properly structured, only one record should be missing a value for the ReportsTo column. In most organizations, everyone has a boss except for the one at the top of the chart.

We can easily track any records that have been orphaned by earlier DELETE statements, leaving them with no one to report to.

Code Listing 5-9: Finding orphaned records

SELECT EmployeeId , FirstName , LastName , ReportsTo , DepartmentId , BirthDate , HireDate , TerminationDate FROM dbo.Employee WHERE ReportsTo IS NULL AND ( TerminationDate > GETDATE() OR TerminationDate IS NULL ); |

If an employee has been terminated, you may or may not care about who they once reported to.

Tip: Run a query like this periodically to track potential data integrity issues as soon as possible. If an Employee is missing its ReportsTo value, we need to supply a placeholder for tracking purposes.

Who’s the boss?

To get the immediate supervisor for any given employee is relatively simple. Join the Employee table back to itself, aliasing one of them as Manager, and one of them as Employee.

Code Listing 5-10: Joining Manager to Employee

SELECT Employee.EmployeeId , Employee.FirstName EmployeeFirstName, Employee.LastName EmployeeLastName, Manager.EmployeeId ManagerId, Manager.FirstName ManagerFirstName, Manager.LastName ManagerLastName FROM dbo.Employee INNER JOIN dbo.Employee Manager ON Manager.EmployeeId = Employee.ReportsTo WHERE Employee.TerminationDate IS NULL ORDER BY ManagerLastName , ManagerFirstName , EmployeeLastName , EmployeeFirstName; |

Note: Anytime you reference the same table more than once, you will need to give each reference a unique name through an alias.

Sometimes you need more details than just the immediate supervisor. You may need to track the level a particular employee is in the hierarchy, see how many levels separate two employees, or report on more than two levels at a time.

In each of these cases, we need to take advantage of the recursive nature of hierarchical tables. Recursive common table expressions (CTEs) will allow us to exploit this power.

A recursive common table expression will have three components:

- Anchor: This will be the initial call to the query composing the CTE. The anchor will generally invoke the recursive call through a UNION statement.

- Recursive call: This will be a subsequent query that references the CTE being defined.

- Termination check: This check is often implied. The recursive calls end when no records are returned from the previous call, which requires that there not be any loops in the data. For example, we will have problems if an employee reports to themselves or to one of their subordinates. We will see shortly how to detect this problem and avoid it.

Now let’s put these pieces together to show the direct reports and their level in the hierarchy.

Code Listing 5-11: Recursive CTE showing direct reports

WITH DirectReports AS ( -- Anchor member definition SELECT e.ReportsTo , e.EmployeeId , e.FirstName , e.LastName , CAST (' ' AS VARCHAR(50)) ManagerFirstName , CAST (' ' AS VARCHAR(50)) ManagerLastName , 0 AS Level FROM dbo.Employee AS e WHERE e.ReportsTo IS NULL UNION ALL -- Recursive member definition SELECT e.ReportsTo , e.EmployeeId , e.FirstName , e.LastName , m.FirstName , m.LastName , d.Level + 1 FROM dbo.Employee AS e INNER JOIN dbo.Employee AS m ON e.ReportsTo = m.EmployeeId INNER JOIN DirectReports AS d ON e.ReportsTo = d.EmployeeId ) SELECT DirectReports.ReportsTo , DirectReports.EmployeeId , DirectReports.FirstName , DirectReports.LastName , DirectReports.ManagerFirstName , DirectReports.ManagerLastName , DirectReports.Level FROM DirectReports ORDER BY LEVEL, managerlastname, lastname |

ReportsTo | EmployeeId | First Name | Last Name | Manager First Name | Manager Last Name | Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

NULL | 1 | Nicole | Bartlett |

|

| 0 |

1 | 13 | Katina | Archer | Nicole | Bartlett | 1 |

1 | 2051 | Gilberto | Arroyo | Nicole | Bartlett | 1 |

1 | 4 | Darnell | Calderon | Nicole | Bartlett | 1 |

1 | 12 | Lindsay | Conner | Nicole | Bartlett | 1 |

1 | 7276 | Elijah | Cruz | Nicole | Bartlett | 1 |

1 | 4151 | Blake | Duarte | Nicole | Bartlett | 1 |

1 | 9 | Daphne | Dudley | Nicole | Bartlett | 1 |

1 | 5 | Desiree | Farmer | Nicole | Bartlett | 1 |

1 | 6 | Holly | Fernandez | Nicole | Bartlett | 1 |

Result Set 5-2: Who's the boss?

We can also incorporate the virtual Level column into the filters:

Code Listing 5-12: Filtering on the level

SELECT DirectReports.ReportsTo , DirectReports.EmployeeId , DirectReports.FirstName , DirectReports.LastName , DirectReports.ManagerFirstName , DirectReports.ManagerLastName , DirectReports.Level FROM DirectReports WHERE DirectReports.Level BETWEEN 7 AND 9 ORDER BY LEVEL, managerlastname, lastname |

In addition to tracking the level, we may often want to get the full path to an individual employee. This is useful information to display and use, but more importantly, we can use it to detect cycles in our data:

Code Listing 5-13: Hierarchy showing the full path through the hierarchy

WITH EmployeeReportingPath AS ( -- Anchor member definition SELECT e.ReportsTo , e.EmployeeId , e.FirstName , e.LastName , '.' + CAST(e.EmployeeId AS VARCHAR(99)) + '.' AS [Path] , 0 AS Level FROM dbo.Employee AS e WHERE e.ReportsTo IS NULL UNION ALL -- Recursive member definition SELECT e.ReportsTo , e.EmployeeId , e.FirstName , e.LastName , CAST(d.Path + '.' + CAST(e.EmployeeId AS VARCHAR(100)) AS VARCHAR(100)) + '.' AS [Path] , d.Level + 1 FROM dbo.Employee AS e INNER JOIN EmployeeReportingPath AS d ON e.ReportsTo = d.EmployeeId ) SELECT EmployeeReportingPath.ReportsTo , EmployeeReportingPath.EmployeeId , EmployeeReportingPath.FirstName , EmployeeReportingPath.LastName , EmployeeReportingPath.Level , EmployeeReportingPath.Path FROM EmployeeReportingPath ORDER BY EmployeeReportingPath.Level , EmployeeReportingPath.LastName; |

This will produce output like the following:

Reports To | Employee Id | First Name | Last Name | Level | Path |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

114 | 549 | Donnie | Calderon | 3 | .1.12.114.549. |

114 | 550 | Louis | Collier | 3 | .1.12.114.550. |

114 | 548 | Nathaniel | Dickson | 3 | .1.12.114.548. |

114 | 543 | Jeannie | Franklin | 3 | .1.12.114.543. |

114 | 552 | Frankie | Glenn | 3 | .1.12.114.552. |

114 | 551 | Robert | Pacheco | 3 | .1.12.114.551. |

114 | 544 | Dorothy | Parrish | 3 | .1.12.114.544. |

114 | 541 | Micheal | Potts | 3 | .1.12.114.541. |

114 | 547 | Spencer | Rowe | 3 | .1.12.114.547. |

114 | 545 | Lillian | Shepherd | 3 | .1.12.114.545. |

Result Set 5-3: Org chart hierarchy showing the full path to an employee

If a number is repeated in the Path column, then there is a cycle, and it will eventually lead to problems. We can add a CASE statement to the output to make these easier to spot.

Code Listing 5-14: Hierarchy query flagging cycles

DECLARE @root INT; SET @root = 5095; WITH EmployeeReportingPath AS ( -- Anchor member definition SELECT e.ReportsTo , e.EmployeeId , e.FirstName , e.LastName , '.' + CAST(e.EmployeeId AS VARCHAR(99)) + '.' AS [Path] , 0 AS Level , 0 AS Cycle FROM dbo.Employee AS e WHERE -- e.EmployeeId = @root-- e.ReportsTo IS NULL UNION ALL -- Recursive member definition SELECT e.ReportsTo , e.EmployeeId , e.FirstName , e.LastName , CAST(d.Path + '.' + CAST(e.EmployeeId AS VARCHAR(100)) AS VARCHAR(100)) + '.' AS [Path] , d.Level + 1 , CASE WHEN d.Path LIKE '%.' + CAST(e.EmployeeId AS VARCHAR(10)) + '.%' THEN 1 ELSE 0 END FROM dbo.Employee AS e INNER JOIN EmployeeReportingPath AS d ON e.ReportsTo = d.EmployeeId WHERE d.Cycle = 0 ) SELECT EmployeeReportingPath.ReportsTo , EmployeeReportingPath.EmployeeId , EmployeeReportingPath.FirstName , EmployeeReportingPath.LastName , EmployeeReportingPath.Level , EmployeeReportingPath.Path , EmployeeReportingPath.Cycle FROM EmployeeReportingPath WHERE EmployeeReportingPath.Cycle = 1 ORDER BY EmployeeReportingPath.Level , EmployeeReportingPath.LastName; |

In this latest query, we have added a new column called Cycle that will have a value of 0 if there is not a cycle detected, or a value of 1 if there was a cycle detected. You can see that we instructed the recursive call not to continue going down a path when a cycle has been detected. Finally, in the WHERE clause for the CALLING query, we add a filter to show only the records that were found with a cycle. We can walk back through the Path for any cycles detected to track where the cycle forms and reroute the employees as appropriate.

Cleaning up this data can often lead to another common problem with hierarchical data: If there is not a path from an Employee record back to the root of the hierarchy, then the Employee record will not be included in these results. Missing data is harder to track down because we don’t know what we don’t see. Fortunately, we can identify the missing records using some set concepts:

Code Listing 5-15: Finding the Employee records missing from the hierarchy view

WITH EmployeeReportingPath AS ( -- Anchor member definition SELECT e.ReportsTo , e.EmployeeId , e.FirstName , e.LastName , CAST(e.EmployeeId AS VARCHAR(100)) AS [Path] , 0 AS Level , 0 AS Cycle FROM dbo.Employee AS e WHERE e.ReportsTo IS NULL UNION ALL -- Recursive member definition SELECT e.ReportsTo , e.EmployeeId , e.FirstName , e.LastName , CAST(d.Path + '.' + CAST(e.EmployeeId AS VARCHAR(100)) + '.' AS VARCHAR(100)) AS [Path] , d.Level + 1 , CASE WHEN d.Path LIKE '%.' + CAST(e.EmployeeId AS VARCHAR(10)) + '.%' THEN 1 ELSE 0 END FROM dbo.Employee AS e INNER JOIN EmployeeReportingPath AS d ON e.ReportsTo = d.EmployeeId WHERE d.Cycle = 0 ) SELECT EmployeeId , FirstName , LastName , ReportsTo FROM dbo.Employee WHERE EmployeeId NOT IN ( SELECT EmployeeReportingPath.EmployeeId FROM EmployeeReportingPath ) ORDER BY LastName , FirstName; |

This will show us employee details for any EmployeeId not included in the recursive query.

Employee Id | First Name | Last Name | Reports To |

|---|---|---|---|

114 | Brendan | Ramsey | 114 |

541 | Micheal | Potts | 114 |

542 | Deborah | Vincent | 114 |

543 | Jeannie | Franklin | 114 |

544 | Dorothy | Parrish | 114 |

545 | Lillian | Shepherd | 114 |

546 | Carla | Villanueva | 114 |

547 | Spencer | Rowe | 114 |

548 | Nathaniel | Dickson | 114 |

549 | Donnie | Calderon | 114 |

Result Set 5-4: Employees missing from the hierarchy view

In this case, the problem is that Employee 114 is flagged as reporting to himself, so there is no path that leads to him. This also means that everyone reporting to this employee is also unreachable.

There’s one final trick that’s helpful when dealing with hierarchical data. Sometimes it may be useful to see the hierarchy not from the root, but from a particular node in the resulting tree. For example, we may want to see the hierarchy details for all the employees who report to this Employee 114 who was causing such a problem.

Code Listing 5-16: Starting the hierarchy below the root

DECLARE @root INT; SET @root = 114; WITH EmployeeReportingPath AS ( -- Anchor member definition SELECT e.ReportsTo , e.EmployeeId , e.FirstName , e.LastName , '.' + CAST(e.EmployeeId AS VARCHAR(99)) + '.' AS [Path] , 0 AS Level , 0 AS Cycle FROM dbo.Employee AS e WHERE e.EmployeeId = @root UNION ALL -- Recursive member definition SELECT e.ReportsTo , e.EmployeeId , e.FirstName , e.LastName , CAST(d.Path + CAST(e.EmployeeId AS VARCHAR(100)) AS VARCHAR(100)) + '.' AS [Path] , d.Level + 1 , CASE WHEN d.Path LIKE '%.' + CAST(e.EmployeeId AS VARCHAR(10)) + '.%' THEN 1 ELSE 0 END FROM dbo.Employee AS e INNER JOIN EmployeeReportingPath AS d ON e.ReportsTo = d.EmployeeId WHERE d.Cycle = 0 ) SELECT EmployeeReportingPath.ReportsTo , EmployeeReportingPath.EmployeeId , EmployeeReportingPath.FirstName , EmployeeReportingPath.LastName , EmployeeReportingPath.Level , EmployeeReportingPath.Path , EmployeeReportingPath.Cycle FROM EmployeeReportingPath ORDER BY EmployeeReportingPath.Level , EmployeeReportingPath.ReportsTo, EmployeeReportingPath.LastName |

All we have to do is change the anchor in the recursive CTE to start with a specific EmployeeId rather than starting where the ReportsTo is NULL.

Summary

In this chapter, we have focused on what happens when a table joins against itself. We saw a practical application of CROSS APPLY and OUTER APPLY. We looked at an advanced optimization of a SQL query as we explored the problem of showing multiple phone numbers for each employee.

We also spent some time exploring hierarchical data and how to deal with some of the common problems that pop up when dealing with hierarchical data, such as orphaned records and cycles in data. We have seen recursive common table expressions in action and how to derive extra data from these queries, such as tracking the level and building the full path to a specific record.

Hierarchical data shows up in many places, and it is important to understand how to query and maintain this data.

- Direct integration with SQL databases for real-time data access

- Interactive dashboards for deeper data exploration

- Advanced analytics to uncover hidden patterns and trends

- Enhanced decision-making with data-driven insights