CHAPTER 4

Spark Internals

In previous chapters, the orientation was more towards practicality and how to get things going with Spark. In this chapter, we are going to go into the concepts behind Spark. We are taking a step back because you will be able to harness the power of Spark in a much better fashion if you understand where all the speed is coming from. In Java source, you might have noticed classes that had RDD in their name. RDD stands for resilient distributed dataset. We mentioned them earlier but didn’t go into them too much. They are often described as being simple collections. In practice, you can treat them that way, and it’s perfectly fine, but there is much more behind them. Let’s dive into the concept of RDD.

Resilient Distributed Dataset (RDD)

We’ve mentioned the concept of RDD but haven’t gone much deeper into it. Let’s have a look at what an RDD really is. An RDD is an immutable and distributed collection of elements that can be operated upon in parallel. It is the basic abstraction that Spark uses to function. RDDs support various kinds of transformations on them. We already used some of them, like map and filter, in previous examples. Every transformation creates a new RDD. One important thing to remember about RDDs is that they are lazily evaluated; when transformation is called upon them, no actual work is done right away. Only the information about the source of RDD is stored and the transformation has to be applied.

Note: RDDs are lazily evaluated data structures. In short, that means there is no processing associated with calling transformations on RDDs right away.

This confuses many developers at first because they perform all the transformations and at the end don’t get the results that they expect. That’s totally fine and is actually the way Spark works. Now you may be wondering: how do we get results? The answer to this is by calling actions. Actions trigger the computation operations on RDDs. In our previous examples, actions were called by using take or saveAsTextFile.

Note: Calling actions trigger computation operations. Action = Computation

There are a lot of benefits from the fact that the transformations are lazily evaluated. Some of them are that operations can be grouped together, reducing the networking between the nodes processing the data; there are no multiple passes over the same data. But there is a pitfall associated with all this. Upon user request for action, Spark will perform the calculations. If the data between the steps is not cached, Spark will reevaluate the expressions again because RDDs are not materialized. We can instruct Spark to materialize the computed operations by calling cache or persist. We will talk about the details soon. Before we go into how caching works, it’s important to mention that the relations between the RDDs are represented as a directed acyclic graph, or DAG. Let’s break it down by looking into a piece of Scala code:

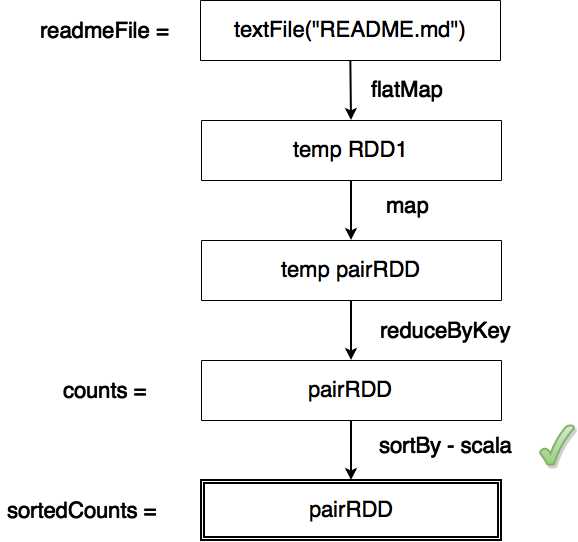

Code Listing 37: Scala Word Count in README.md file, Ten Most Common Words

val readmeFile = sc.textFile("README.md") val counts = readmeFile.flatMap(line => line.split(" ")). map(word => (word, 1)). reduceByKey(_ + _) val sortedCounts = counts.sortBy(_._2, false)

sortedCounts.take(10).foreach(println) |

An RDD is created from a README.md file. Calling a flatMap transformation on the lines in the file creates an RDD too, and then a pair RDD is created with a word and a number one. Numbers paired with the same word are then added together. After that, we sort them by count, take the first ten, and print them. The first action that triggers computation is sortBy. It’s a Scala-specific operation, and it needs concrete data to do the sort so that computation is triggered. Let’s have a look at the DAG up until that point:

Figure 44: Compute Operation Directed Acyclic Graph

Figure 44 shows how RDDs are computed. Vertices are RDDs and edges are transformations and actions on RDDs. Only actions can trigger computation. In our example, this happens when we call the sortBy action. There are a fair number of transformations in Spark, so we are only going to go over the most common ones.

Table 3: Common Spark Transformations

Transformation | Description |

|---|---|

filter(func) | Return a new dataset formed by selecting those elements of the source on which function returns true. |

map(func) | Return a new distributed dataset formed by passing each element of the source through a function. |

flatMap(func) | Similar to map, but each input item can be mapped to 0 or more output items (so the function should return a sequence rather than a single item). |

distinct([numTasks])) | Return a new dataset that contains the distinct elements of the source dataset. |

sample(withReplacement, fraction, seed) | Sample a fraction of the data, with or without replacement, using a given random number generator seed. Often used when developing or debugging. |

union(otherDataset) | Return a new dataset that contains the union of the elements in the source dataset and the argument. |

intersection(otherDataset) | Return a new RDD that contains the intersection of elements in the source dataset and the argument. |

cartesian(otherDataset) | When called on datasets of types T and U, returns a dataset of (T, U) pairs (all pairs of elements). |

Source: http://spark.apache.org/docs/latest/programming-guide.html#transformations | |

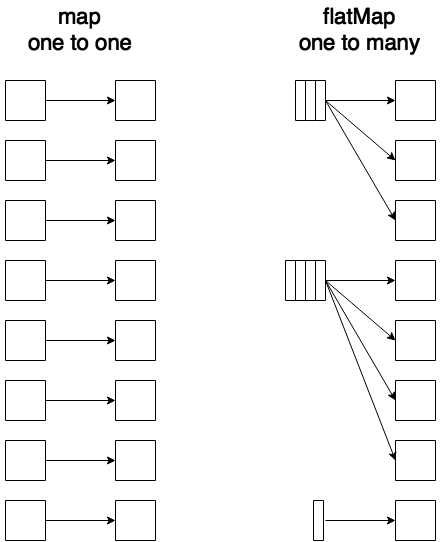

Most of the people starting out with Spark get confused with flatMap and map functions. The easiest way to wrap your head around it is to remember that map is a one-to-one function and flatmap is one to many. Input for flatMap is usually a collection of elements. In our examples, we started out with lines of text. The lines of text were then split into words. Every line contains zero or multiple words. But we want every word to appear in the final RDD separately, so we used a flatMap function. Just so that it stays with you longer, let’s have a look at the following figure:

Figure 45: Spark Transformations Map and flatMap in Action

Some of the mentioned transformations are mostly used with simple RDDs, while some are more often used with pair RDDs. We’ll just mention them for now and will go in depth later. Let’s look at some of the most common actions:

Table 4: Common Spark Actions

Transformation | Description |

|---|---|

collect() | Return all the elements of a dataset as an array at the driver program. This is usually useful after a filter or other operation that returns a sufficiently small subset of data. Be careful when calling this. |

count() | Return the number of elements in the dataset. |

first() | Return the first element of the dataset (similar to take(1)). |

take(n) | Return an array with the first n elements of the dataset. |

takeSample(withReplacement, num, [seed]) | Return an array with a random sample of “num” elements of the dataset, with or without replacement, optionally pre-specifying a random number generator seed. |

reduce(func) | Aggregate the elements of dataset using a function (which takes two arguments and returns one). The function should be commutative and associative so that it can be computed correctly in parallel. |

foreach(func) | Run a function on each element of the dataset. Usually used to interact with external storage systems. |

saveAsTextFile(path) | Write the elements of the dataset as a text file (or set of text files) in a given directory in the local file system, HDFS or any other Hadoop-supported file system. Spark will call toString on each element to convert it to a line of text in the file. |

Source: http://spark.apache.org/docs/latest/programming-guide.html#actions | |

Now that we’ve covered most commonly used actions and transformations, it might be a good thing to mention some helper operations that come in very handy when developing applications with Spark. One of them is toDebugString:

Code Listing 38: Result of Running toDebugString in Spark Shell

scala> sortedCounts.toDebugString res6: String = (2) MapPartitionsRDD[26] at sortBy at <console>:25 [] | ShuffledRDD[25] at sortBy at <console>:25 [] +-(2) MapPartitionsRDD[22] at sortBy at <console>:25 [] | ShuffledRDD[21] at reduceByKey at <console>:25 [] +-(2) MapPartitionsRDD[20] at map at <console>:24 [] | MapPartitionsRDD[19] at flatMap at <console>:23 [] | MapPartitionsRDD[18] at textFile at <console>:21 [] | README.md HadoopRDD[17] at textFile at <console>:21 [] |

The result is a text representation of the Directed Acyclic Graph associated with the value or variable upon which we called a toDebugString method. Earlier we mentioned that we could avoid unnecessary computation by caching results. We’ll cover this in the next section.

Caching RDDs

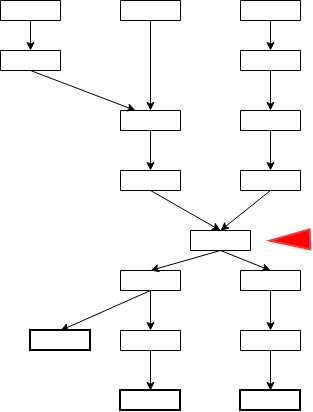

Most of the time the directed acyclic graph will not be simple hierarchical structure. In practice it may involve a lot of levels that branch into new levels.

Figure 46: Complex Directed Acyclic Graph with Caching Candidate

When we call actions at the end for every called action because of the lazy evaluation, the computation goes all the way to the beginning for every one of them. It’s a good practice to cache RDDs that are sources for generating a lot of other RDDs. In Figure 46, the RDD marked with a red marker is, definitely, a candidate for caching. There are two methods that you can use for caching the RDD. One is cache and the other is persist. Method cache is just a shorthand for persist, where a default storage level MEMORY_ONLY is used. Let’s have a look at cache storage levels:

Table 5: Spark Storage Levels

Storage Level | Description |

MEMORY_ONLY | Store RDD as deserialized Java objects in the JVM. If the RDD does not fit in memory, some partitions will not be cached and will be recomputed on the fly each time they're needed. This is the default level. |

MEMORY_AND_DISK | Store RDD as deserialized Java objects in the JVM. If the RDD does not fit in memory, store the partitions that don't fit on disk, and read them from there when they're needed. |

MEMORY_ONLY_SER | Store RDD as serialized Java objects (one byte array per partition). This is generally more space-efficient than deserialized objects, especially when using a fast serializer, but more CPU-intensive to read. |

MEMORY_AND_DISK_SER | Similar to MEMORY_ONLY_SER, but spill partitions that don't fit in memory to disk instead of recomputing them on the fly each time they're needed. |

DISK_ONLY | Store the RDD partitions only on disk. |

MEMORY_ONLY_2, MEMORY_AND_DISK_2, etc. | Same as previous levels, but replicate each partition on two cluster nodes. |

OFF_HEAP | Is in experimental phase. |

Source: http://spark.apache.org/docs/latest/programming-guide.html#rdd-persistence | |

Spark systems are usually oriented towards having a lot of CPU cores and a lot of RAM. You have to have very good reasons to store something on disk. Most of the time this option is only used with SSD disks. There was a comparison table earlier in the book when we talked about basics of big data processing where a CPU cycle was a baseline representing one second. RAM access was six minutes and access to SSD disk two to six days. Rotational disk, by comparison, takes one to twelve months. Remember that fact when persisting your data to the disk.

Tip: Spark needs cores and RAM; most of the time it’s advisable to avoid disk.

This doesn’t mean that you should avoid it at all cost, but you have to be aware of significant performance drops when it comes to storing data on disk. If you remember the story about Spark’s sorting record, the amount of data sorted definitely didn’t fit only into RAM, and disk was also heavily used. It’s just important to be aware of the fact that disk is significantly slower than RAM. Sometimes even going to disk might be a much better option than fetching elements from various network storages or something similar. Caching definitely comes in handy in those situations. Let’s have a look how we would cache an RDD. In this chapter, we are mostly using Scala language because we are discussing concepts and not implementations in specific languages. Let’s cache an RDD:

Code Listing 39: Calling Cache on RDD

scala> sortedCounts.cache() res7: sortedCounts.type = MapPartitionsRDD[26] at sortBy at <console>:25 scala> sortedCounts.take(10).foreach(println) (,66) (the,21) (Spark,14) (to,14) (for,11) (and,10) (a,9) (##,8) (run,7) (can,6) |

RDDs are evaluated lazily, so just calling cache has no effect. That’s why we are taking the first ten elements from the RDD and printing them. We are calling action and calling action triggers caching to take place.

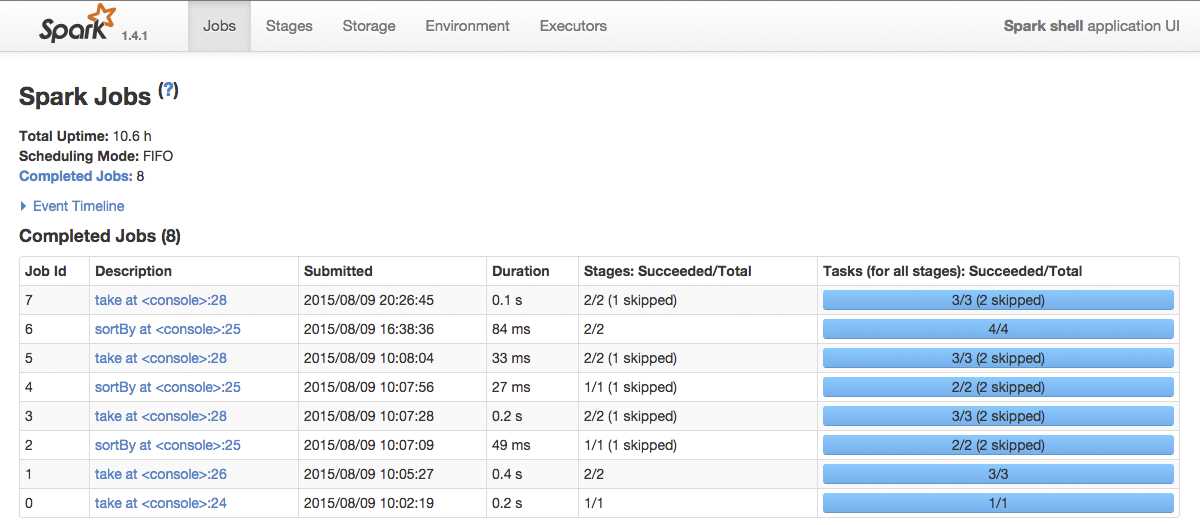

We didn’t mention it earlier, but when you run a Spark or Python shell it also starts a small web application that gives you overview over resources the shell uses, environment, and so on. You can have a look at it by opening your browser and navigating to http://localhost:4040/. The result of this action should look something like:

Figure 47: Spark Shell Application UI

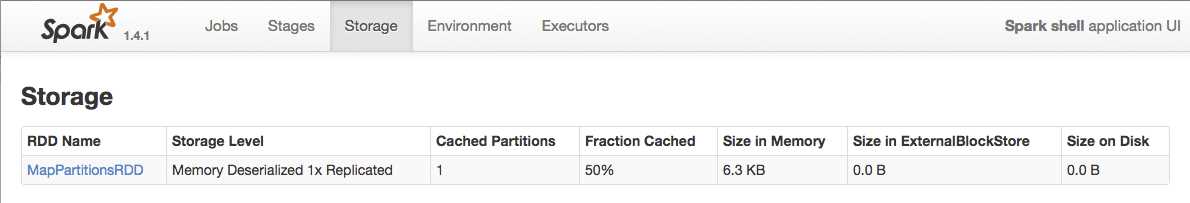

By default, Spark Shell Application UI opens the Jobs tab. Navigate to the Storage tab:

Figure 48: Spark Shell Application UI Storage Details

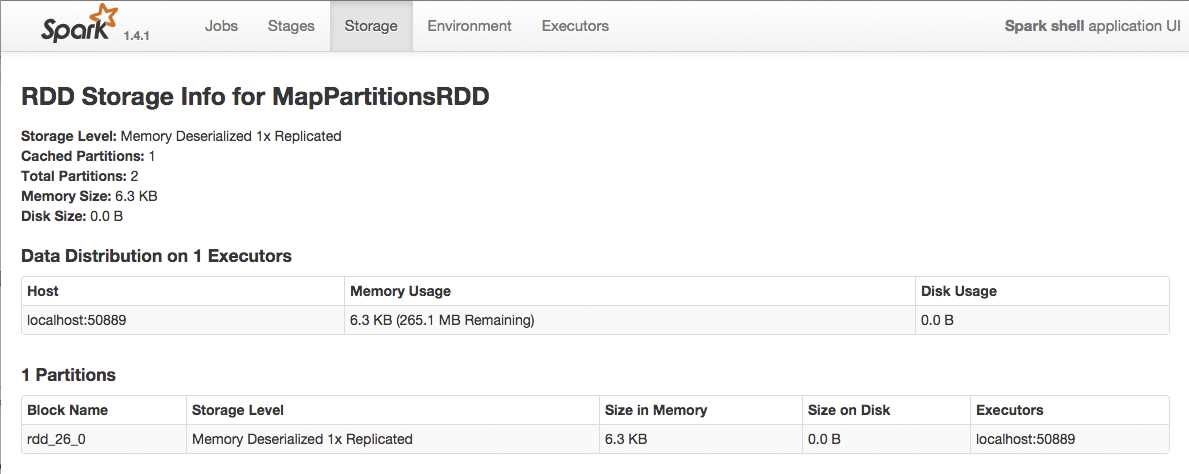

The RDD that we cached by calling cache is visible in the Spark Shell Application UI Storage Tab. We can even find out details by clicking on RDD Name:

Figure 49: Spark Shell Application UI Storage Details for a Single RDD

If you want to stop caching your RDDs in order to free up resources for further processing, you can simply call the unpersist method on a particular RDD. This method has an immediate effect, and you don’t have to wait for when the RDD is recomputed. Here is an example on how unpersist works:

Code Listing 40: Calling Unpersist on RDD

scala> sortedCounts.unpersist() res3: sortedCounts.type = MapPartitionsRDD[9] at sortBy at <console>:25 |

You can check the effects of calling cache and unpersist methods in Spark’s WebUI, which we showed in earlier figures.

By now we covered enough to get you going with RDDs. In previous examples, we just mentioned Pair RDDs and worked with them a bit, but we didn’t discuss them in depth. In the next section we are going to explain how to use Pair RDDs.

Pair RDDs

Pair RDDs behave pretty similar to basic RDDs. The main difference is that RDD elements are key value pairs, and key value pairs are a natural fit for distributed computing problems. Pair RDDs are heavily used to perform various kinds of aggregations and initial Extract Transform Load procedure steps. Performance-wise there’s one important, rarely mentioned fact about them: Pair RDDs don’t spill on disk. Only basic RDDs can spill on disk. This means that a single Pair RDD must fit into computer memory. If Pair RDD content is larger than the size of the smallest amount of RAM in the cluster, it can’t be processed. In our previous examples we already worked with Pair RDDs, we just didn’t go in depth with them.

We’ll start with the simplest possible example here. We are going to create RDDs from a collection of in-memory elements defined by ourselves. To do that, we will call the parallelize Spark context function. Java API is a bit more strongly typed and can’t do automatic conversions, so Java code will be a bit more robust since we have to treat the elements with the right types from the start. In this example, there are no significant elegancy points gained for using Java 8, so we’ll stick with Java 7. As in the previous chapters let’s start with Scala:

Code Listing 41: Simple Pair RDD Definition in Scala

val pairs = List((1,1), (1,2), (2,3), (2, 4), (3, 0)) val pairsRDD = sc.parallelize(pairs) pairsRDD.take(5) |

Code Listing 42: Simple Pair RDD Definition in Scala Result

scala> pairsRDD.take(5) res2: Array[(Int, Int)] = Array((1,1), (1,2), (2,3), (2,4), (3,0)) |

Code Listing 43: Simple Pair RDD Definition in Python

pairs = [(1, 1), (1, 2), (2, 3), (2, 4), (3, 0)] pairs_rdd = sc.parallelize(pairs) pairs_rdd.take(5) |

Code Listing 44: Simple Pair RDD Definition in Python Result

>>> pairs_rdd.take(5) [(1, 1), (1, 2), (2, 3), (2, 4), (3, 0)] |

As mentioned earlier, the Java example will include a few more details. There is no interactive shell for Java, so we are simply going to output the results of Java pair RDD creation to a text file. To define pairs we are going to use the Tuple2 class provided by Scala. In the previous example, the conversion between the types is done automatically by Scala, so it’s a lot less code than with Java. Another important difference is that in Java parallelize works only with basic RDDs. To create pair RDDs in Java, we have to use the parallelizePairs call from initialized context. Let’s start by defining a class:

Code Listing 45: Simple Pair RDD Definition in Java

package com.syncfusion.succinctly.spark.examples; import java.util.Arrays; import java.util.List; import org.apache.spark.SparkConf; import org.apache.spark.api.java.JavaPairRDD; import org.apache.spark.api.java.JavaSparkContext; import scala.Tuple2; public class PairRDDJava7 { public static void main(String[] args) { if (args.length < 1) { System.err.println("Please provide a full path to the output file"); System.exit(0); } SparkConf conf = new SparkConf().setAppName("PairRDDJava7").setMaster("local"); JavaSparkContext context = new JavaSparkContext(conf); List<Tuple2<Integer, Integer>> pairs = Arrays.asList( new Tuple2(1, 1), new Tuple2<Integer, Integer>(1, 2), new Tuple2<Integer, Integer>(2, 3), new Tuple2<Integer, Integer>(2, 4), new Tuple2<Integer, Integer>(3, 0)); JavaPairRDD<Integer, Integer> pairsRDD = context.parallelizePairs(pairs); pairsRDD.saveAsTextFile(args[0]); } } |

Just as a short refresher, to submit the class to Spark you will need to rerun the packaging steps with Maven that are described in earlier chapters. Note that the way you submit may vary depending on what operating system you are using:

Code Listing 46: Submitting PairRDDJava7 to Spark on Linux Machines

$ ./bin/spark-submit \ --class com.syncfusion.succinctly.spark.examples.PairRDDJava7 \ --master local \ /root/spark/SparkExamples-0.0.1-SNAPSHOT.jar \ /root/spark/resultspair |

When jobs are submitted, the results of operations are usually not outputted in a log. We will show additional ways to store data in permanent storage later. For now, the results will be saved to a folder. Here is the resulting output file content:

Code Listing 47: Output File for PairRDDJava7 Task Submitted to Spark

(1,1) (1,2) (2,3) (2,4) (3,0) |

Previous examples show how to define Pair RDDs from basic in-memory data structures. Now we are going to go over basic operations with Pair RDDs. Pair RDDs have all the operations that the basic ones have, so, for instance, you can filter them out based on some criteria.

Aggregating Pair RDDs

This is a very common use case when it comes to Pair RDDs. When we did a word count, we used the reduceByKey transformation on a Pair RDD. When reduceByKey is called, a pair RDD is returned with the same keys as the original RDD, and the values are aggregation done on every value having the same key. Let’s have a look at what the result would be for calling it on pairs (1, 1), (1, 2), (2, 3), (2, 4), and (3, 0), which we used in previous examples. We are going to take five elements, although we know the result won’t necessarily have a size of all the elements combined. This is just to trigger computing and to display some results. Again, to run with Java you will have to submit a jar to Spark. To keep things shorter, in Java we will just show the functional part of code in the examples:

Code Listing 48: reduceByKey in Action with Scala

scala> pairsRDD.reduceByKey(_+_).take(5) res4: Array[(Int, Int)] = Array((1,3), (2,7), (3,0)) |

Code Listing 49: reduceByKey in Action with Python

>>> pairs_rdd.reduceByKey(lambda a, b: a + b).take(5) |

Code Listing 50: reduceByKey in Action with Java 7

JavaPairRDD<Integer, Integer> reduceByKeyResult = pairsRDD .reduceByKey(new Function2<Integer, Integer, Integer>() { public Integer call(Integer a, Integer b) { return a + b; } }); reduceByKeyResult.saveAsTextFile(args[0]); |

Code Listing 51: reduceByKey in Action with Java 8

JavaPairRDD<Integer, Integer> reduceByKeyResult = pairsRDD.reduceByKey((a, b) -> a + b);

reduceByKeyResult.saveAsTextFile(args[0]); |

Note that with Java we didn’t call the take operation because saving RDDs into a text file iterates over all RDD elements anyway. The resulting file will look like the following:

Code Listing 52: Java reduceByKey Output

(1,3) (3,0) (2,7) |

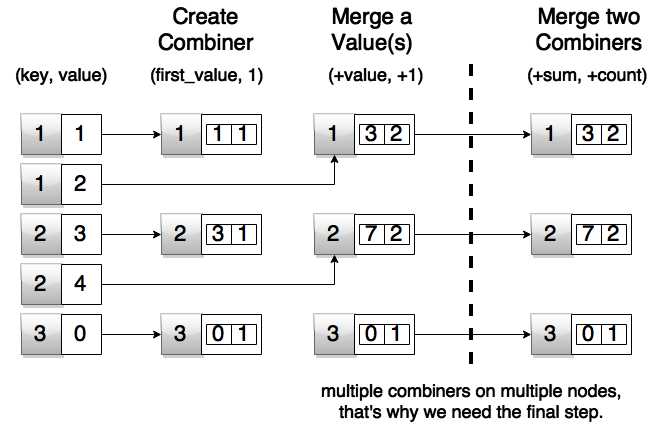

Let’s go a bit further with the concept. The example was relatively simple, because all we had to do was add everything up. It can get quite complicated in real life, though. For example, calculating average value for a key is a pretty common problem in practice. It’s not straightforward and there are some steps to it. In the first step, we have to determine the total count of all the key occurrences. The second step is to combine all the elements and add them up by key. In the final step, we have to divide the sum by total counts per key. To achieve this goal we are going to use the combineByKey function. It’s a bit complex, so we will break it down into parts. To make explaining easier, we are again going to use our list ((1,1), (1,2), (2,3), (2, 4), (3, 0)). We will display it graphically after giving textual explanation just to make sure you understand it. I know it might feel a bit challenging at first, but try to read this section a couple of times if it doesn’t sit right away. Let’s start with primary explanation:

- Create a Combiner – First aggregation step done for every key. In essence, for every key we create a list of pairs containing values and a value 1.

- Merge a Value – Per every key we are going to add up the sums and increase the total number of elements by one.

- Merge two Combiners – In the final step we are going to add up all the sums together with all the counts. This is also necessary because parts of the calculation are done on separate machines. When the results come back we combine them together.

We are going to go over examples in programming languages soon. Before giving any code samples, let’s have a look at a graphical description, just so that it sits better. To some of you, the final step might look a bit unnecessary, but remember that Spark processes data in parallel and that you have to combine the data that comes back from all of the nodes in the cluster. To make our example functional in the final step (shown in the following figure) we have to go over all of the returned results and divide the sum with count. But that’s just basic mapping, and we won’t go much into it. Here is a figure showing how combineByKey works:

Figure 50: Spark combineByKey in Action

Here is what the code would look like in Scala:

Code Listing 53: Spark combineByKey Scala Code

val pairAverageResult = pairsRDD.combineByKey( (v) => (v, 1), (acc: (Int, Int), v) => (acc._1 + v, acc._2 + 1), (acc1: (Int, Int), acc2: (Int, Int)) => (acc1._1 + acc2._1, acc1._2 + acc2._2) ).map{ case (key, value) => (key, value._1 / value._2.toFloat)} |

The result of running previous code in Spark Shell:

Code Listing 54: Spark combineByKey Result in Spark Shell

scala> pairAverageResult.take(5); res6: Array[(Int, Float)] = Array((1,1.5), (2,3.5), (3,0.0)) |

We are just trying stuff in Spark Shell; the simplest method to partially debug RDDs is to take the first n elements out of them. We know that we only have three keys in collection, so taking five out will definitely print them all out. The purpose of these examples is not so much on performance and production level optimization, but more that you get comfortable with using Spark API until the end of the book. We covered a pretty complex example in Scala. Let’s have a look at how this would look in Python:

Code Listing 55: Spark combineByKey Python code

pair_average_result = pairs_rdd.combineByKey((lambda v: (v, 1)), (lambda a1, v: (a1[0] + v, a1[1] + 1)), (lambda a2, a1: (a2[0] + a1[0], a2[1] + a1[1])) ).map(lambda acc: (acc[0], (acc[1][0] / float(acc[1][1])))) |

Now that we have the code, let’s have a look at the result:

Code Listing 56: Spark combineByKey Result in PySpark

>>> pair_average_result.take(5) |

The Scala and Python examples are relatively similar. Now we are going to show the Java 7 version. You will notice there is much more code when compared to Scala and Python. For completeness sake, let’s have a look at complete code:

Code Listing 57: Spark combineByKey Java7 Code

package com.syncfusion.succinctly.spark.examples; import java.io.PrintWriter; import java.io.Serializable; import java.util.Arrays; import java.util.List; import java.util.Map; import org.apache.spark.SparkConf; import org.apache.spark.api.java.JavaPairRDD; import org.apache.spark.api.java.JavaSparkContext; import org.apache.spark.api.java.function.Function; import org.apache.spark.api.java.function.Function2; import scala.Tuple2; public class CombineByKeyJava7 { public static class AverageCount implements Serializable { public int _sum; public int _count; public AverageCount(int sum, int count) { this._sum = sum; this._count = count; } public float average() { return _sum / (float) _count; } } public static void main(String[] args) throws Exception { if (args.length < 1) { System.err.println("Please provide a full path to the output file"); System.exit(0); } SparkConf conf = new SparkConf().setAppName("CombineByKeyJava7").setMaster("local"); JavaSparkContext context = new JavaSparkContext(conf); Function<Integer, AverageCount> createCombiner = new Function<Integer, AverageCount>() { public AverageCount call(Integer x) { return new AverageCount(x, 1); } }; Function2<AverageCount, Integer, AverageCount> mergeValues = new Function2<AverageCount, Integer, AverageCount>() { public AverageCount call(AverageCount a, Integer x) { a._sum += x; a._count += 1; return a; } }; Function2<AverageCount, AverageCount, AverageCount> mergeTwoCombiners = new Function2<AverageCount, AverageCount, AverageCount>() { public AverageCount call(AverageCount a, AverageCount b) { a._sum += b._sum; a._count += b._count; return a; } }; List<Tuple2<Integer, Integer>> pairs = Arrays.asList(new Tuple2(1, 1), new Tuple2<Integer, Integer>(1, 2), new Tuple2<Integer, Integer>(2, 3), new Tuple2<Integer, Integer>(2, 4), new Tuple2<Integer, Integer>(3, 0)); JavaPairRDD<Integer, Integer> pairsRDD = context.parallelizePairs(pairs); JavaPairRDD<Integer, AverageCount> pairAverageResult = pairsRDD.combineByKey(createCombiner, mergeValues, mergeTwoCombiners); Map<Integer, AverageCount> resultMap = pairAverageResult.collectAsMap(); PrintWriter writer = new PrintWriter(args[0]); for (Integer key : resultMap.keySet()) { writer.println(key + ", " + resultMap.get(key).average()); } writer.close(); } } |

Code should produce an output file according to parameters you give it when running. In my case, it was written to the combineByKey.txt file and it looked like:

Code Listing 58: Spark combineByKey Java 7 Version in combineByKey.txt

2, 3.5 1, 1.5 3, 0.0 |

Again, this seems like a lot of code, but I guess Java veterans are used to it—perhaps not liking it, but that’s the way it is with pre-Java 8 versions. Just as a comparison, we’ll have a look at the algorithmic part with Java 8:

Code Listing 59: Spark combineByKey Java 8 Algorithmic Part

JavaPairRDD<Integer, AverageCount> pairAverageResult = pairsRDD.combineByKey( x -> new AverageCount(x, 1), (a, x) -> { a._sum += x; a._count += 1; return a; }, (a, b) -> { a._sum += b._sum; a._count += b._count; return a; }); |

Note that imports, parameter processing, and class definition remain as in the previous example. Java examples have more code because at the moment Java doesn’t support an interactive shell. The submit task will also be pretty similar to the Java 7 example. You will probably just give your class a different name. All in all, there is a lot less code in this example as you can see. Since there is less code, it’s probably even easier to maintain it.

In this section, we demonstrated the basics of data aggregation. Again, there is more to it than shown here, but the goal of this book is to get you going. In the next section we are going to deal with data grouping.

Data Grouping

Grouping is very similar to aggregation. The difference is that it only groups data; there is no computing of values per group as in aggregation. Grouping can be used as a basis for other operations, like join and intersect between two Pair RDDs, but doing that is usually a very bad idea because it is not very efficient. In the previous section we used simple integer key value pairs. Examples in this section wouldn’t make much sense if we did that, so we are going to define simple data sets from the three languages that we are using in this book. To go over examples for this section, we are going to define a simple example about used cars. The inside records will be a year, a name, and a color. We will also create a Pair RDD. Let’s start with the Scala version and then do the same for Python and Java:

Code Listing 60: Scala Used Cars Initial Data Definition

case class UsedCar(year: Int, name: String, color: String) val cars = List( UsedCar(2012, "Honda Accord LX", "gray"), UsedCar(2008, "Audi Q7 4.2 Premium", "white"), UsedCar(2006, "Mercedes-Benz CLS-Class CLS500", "black"), UsedCar(2012, "Mitsubishi Lancer", "black"), UsedCar(2010, "BMW 3 Series 328i", "gray"), UsedCar(2006, "Buick Lucerne CX", "gray"), UsedCar(2006, "GMC Envoy", "red") ) |

Code Listing 61: Python Used Cars Initial Data Definition

cars = [ (2012, 'Honda Accord LX', 'gray'), (2008, 'Audi Q7 4.2 Premium', 'white'), (2006, 'Mercedes-Benz CLS-Class CLS500', 'black'), (2012, 'Mitsubishi Lancer', 'black'), (2010, 'BMW 3 Series 328i', 'gray'), (2006, 'Buick Lucerne CX', 'gray'), (2006, 'GMC Envoy', 'red') ] |

Code Listing 62: Java Used Cars Initial Data Definition

public static class UsedCar implements Serializable { public int _year; public String _name; public String _color;

public UsedCar(int year, String name, String color) { this._year = year; this._name = name; this._color = color; } } // rest of the code coming soon List<UsedCar> cars = Arrays.asList( new UsedCar(2012, "Honda Accord LX", "gray"), new UsedCar(2008, "Audi Q7 4.2 Premium", "white"), new UsedCar(2006, "Mercedes-Benz CLS-Class CLS500", "black"), new UsedCar(2012, "Mitsubishi Lancer", "black"), new UsedCar(2010, "BMW 3 Series 328i", "gray"), new UsedCar(2006, "Buick Lucerne CX", "gray"), new UsedCar(2006, "GMC Envoy", "red") ); |

We’ll create Pair RDDs with year being a key and the entry itself as a value:

Code Listing 63: Scala Pair RDD with Year as a Key and Entry as a Value

val carsByYear = sc.parallelize(cars).map(x => (x.year, x)) |

Code Listing 64: Python Pair RDD with Year as a Key and Entry as a Value

cars_by_year = sc.parallelize(cars).map(lambda x : (x[0], x)) |

With Java we would have to repeat a lot of code here, so we’ll just skip it for now and provide the final example at the end. Our goal now is to fetch all used car offerings for a year. We’ll use year 2006 in our examples. To do this, we are going to use groupBy method. Most of the time, reduceByKey and combineByKey have better performance, but groupBy comes in very handy when we need to group the data together. Note that grouping transformations may result in big pairs. Remember that any given Pair RDD element must fit into memory. RDD can split to disk, but a single Pair RDD instance must fit into memory. Let’s group the dataset by year and then we’ll look up all the values for 2006 in Scala:

Code Listing 65: Scala Used Cars from 2006

scala> carsByYear.groupByKey().lookup(2006) res6: Seq[Iterable[UsedCar]] = ArrayBuffer(CompactBuffer(UsedCar(2006,Mercedes-Benz CLS-Class CLS500,black), UsedCar(2006,Buick Lucerne CX,gray), UsedCar(2006,GMC Envoy,red))) |

With Python we will show how the whole data structure looks, just so that you get the overall impression:

Code Listing 66: Python Showing All Available Used Cars Grouped by Years

>>> cars_by_year.groupByKey().map(lambda x : (x[0], list(x[1]))).collect() [(2008, [(2008, 'Audi Q7 4.2 Premium', 'white')]), (2012, [(2012, 'Honda Accord LX', 'gray'), (2012, 'Mitsubishi Lancer', 'black')]), (2010, [(2010, 'BMW 3 Series 328i', 'gray')]), (2006, [(2006, 'Mercedes-Benz CLS-Class CLS500', 'black'), (2006, 'Buick Lucerne CX', 'gray'), (2006, 'GMC Envoy', 'red')])] |

Code Listing 67: Java Example for groupByKey

package com.syncfusion.succinctly.spark.examples; import java.io.PrintWriter; import java.io.Serializable; import java.util.Arrays; import java.util.List; import org.apache.spark.SparkConf; import org.apache.spark.api.java.JavaPairRDD; import org.apache.spark.api.java.JavaSparkContext; import org.apache.spark.api.java.function.PairFunction; import scala.Tuple2; public class GroupByKeyJava7 { public static class UsedCar implements Serializable { public int _year; public String _name; public String _color; public UsedCar(int year, String name, String color) { this._year = year; this._name = name; this._color = color; } } public static void main(String[] args) throws Exception { if (args.length < 1) { System.err.println("Please provide a full path to the output file"); System.exit(0); } SparkConf conf = new SparkConf() .setAppName("GroupByKeyJava7").setMaster("local"); JavaSparkContext context = new JavaSparkContext(conf); List<UsedCar> cars = Arrays.asList( new UsedCar(2012, "Honda Accord LX", "gray"), new UsedCar(2008, "Audi Q7 4.2 Premium", "white"), new UsedCar(2006, "Mercedes-Benz CLS-Class CLS500", "black"), new UsedCar(2012, "Mitsubishi Lancer", "black"), new UsedCar(2010, "BMW 3 Series 328i", "gray"), new UsedCar(2006, "Buick Lucerne CX", "gray"), new UsedCar(2006, "GMC Envoy", "red") ); JavaPairRDD<Integer, UsedCar> carsByYear = context.parallelize(cars) .mapToPair(new PairFunction<UsedCar, Integer, UsedCar>() { public Tuple2<Integer, UsedCar> call(UsedCar c) { return new Tuple2<Integer, UsedCar>(c._year, c); } }); List<Iterable<UsedCar>> usedCars2006 = carsByYear.groupByKey().lookup(2006); PrintWriter writer = new PrintWriter(args[0]); for (Iterable<UsedCar> usedCars : usedCars2006) { for (UsedCar usedCar : usedCars) { writer.println( usedCar._year + ", " + usedCar._name + ", " + usedCar._color); } } writer.close(); } } |

The result of running the Java example is a file containing offerings for cars from 2006:

Code Listing 68: Result of Java Example Processing

$ cat /syncfusion/spark/out/groupByKey.txt 2006, Mercedes-Benz CLS-Class CLS500, black 2006, Buick Lucerne CX, gray 2006, GMC Envoy, red |

With this example, we went over how to group data together in Spark. In the next section we are going to go over sorting pair RDDs.

Sorting Pair RDDs

Sorting is a very important feature in everyday computer applications. People perceive data and notice important differences and trends much better if data is sorted. In many situations, the sorting happens by time. Other requirements, like sorting alphabetically, are totally valid. There is one important fact that you have to remember:

Note: Sorting is an expensive operation. Try to sort smaller sets.

When we sort, all of the machines in the cluster have to contact each other and exchange multiple data sets over and over again throughout the time it takes to sort the data. So, when you need sorting, try to invoke it on smaller data sets. We will use data defined in the previous section. In this section, we will simply sort it by year:

Code Listing 69: Scala Sorting Car Offerings by Year Descending

scala> carsByYear.sortByKey(false).collect().foreach(println) (2012,UsedCar(2012,Honda Accord LX,gray)) (2012,UsedCar(2012,Mitsubishi Lancer,black)) (2010,UsedCar(2010,BMW 3 Series 328i,gray)) (2008,UsedCar(2008,Audi Q7 4.2 Premium,white)) (2006,UsedCar(2006,Mercedes-Benz CLS-Class CLS500,black)) (2006,UsedCar(2006,Buick Lucerne CX,gray)) (2006,UsedCar(2006,GMC Envoy,red)) |

Code Listing 70: Python Sorting Car Offerings by Year

cars_sorted_by_years = cars_by_year.sortByKey().map(lambda x : (x[0], list(x[1]))).collect() for x in cars_sorted_by_years: print str(x[0]) + ', ' + x[1][1] + ', '+ x[1][2] |

Code Listing 71: Python Results of Running in PySpark

>>> for x in cars_sorted_by_years: ... print str(x[0]) + ', ' + x[1][1] + ', '+ x[1][2] ... 2006, Mercedes-Benz CLS-Class CLS500, black 2006, Buick Lucerne CX, gray 2006, GMC Envoy, red 2008, Audi Q7 4.2 Premium, white 2010, BMW 3 Series 328i, gray 2012, Honda Accord LX, gray 2012, Mitsubishi Lancer, black >>> |

The Java example will again contain a bit more code due to reasons we’ve already mentioned:

Code Listing 72: Code for Sorting by Keys in Java

package com.syncfusion.succinctly.spark.examples; import java.io.PrintWriter; import java.io.Serializable; import java.util.Arrays; import java.util.List; import org.apache.spark.SparkConf; import org.apache.spark.api.java.JavaPairRDD; import org.apache.spark.api.java.JavaSparkContext; import org.apache.spark.api.java.function.PairFunction; import scala.Tuple2; public class SortByKeyJava7 { public static class UsedCar implements Serializable { public int _year; public String _name; public String _color; public UsedCar(int year, String name, String color) { this._year = year; this._name = name; this._color = color; } } public static void main(String[] args) throws Exception { if (args.length < 1) { System.err.println("Please provide a full path to the output file"); System.exit(0); } SparkConf conf = new SparkConf().setAppName("SortByKeyJava7").setMaster("local"); JavaSparkContext context = new JavaSparkContext(conf); List<UsedCar> cars = Arrays.asList( new UsedCar(2012, "Honda Accord LX", "gray"), new UsedCar(2008, "Audi Q7 4.2 Premium", "white"), new UsedCar(2006, "Mercedes-Benz CLS-Class CLS500", "black"), new UsedCar(2012, "Mitsubishi Lancer", "black"), new UsedCar(2010, "BMW 3 Series 328i", "gray"), new UsedCar(2006, "Buick Lucerne CX", "gray"), new UsedCar(2006, "GMC Envoy", "red") ); JavaPairRDD<Integer, UsedCar> carsByYear = context.parallelize(cars) .mapToPair(new PairFunction<UsedCar, Integer, UsedCar>() { public Tuple2<Integer, UsedCar> call(UsedCar c) { return new Tuple2<Integer, UsedCar>(c._year, c); } }); List<Tuple2<Integer, UsedCar>> sortedCars = carsByYear.sortByKey().collect(); PrintWriter writer = new PrintWriter(args[0]); for (Tuple2<Integer, UsedCar> usedCar : sortedCars) { writer.println( usedCar._2()._year + ", " + usedCar._2()._name + ", " + usedCar._2()._color); } writer.close(); } } |

The results of Java processing are:

Code Listing 73: Results of Java Code Sorting

$ cat /syncfusion/spark/out/sortByKey.txt 2006, Mercedes-Benz CLS-Class CLS500, black 2006, Buick Lucerne CX, gray 2006, GMC Envoy, red 2008, Audi Q7 4.2 Premium, white 2010, BMW 3 Series 328i, gray 2012, Honda Accord LX, gray 2012, Mitsubishi Lancer, black |

There is one more important group of operations that we can do with Pair RDDs. It’s joining, and we’ll discuss it in the next section

Join, Intersect, Union, and Difference Operations on Pair RDDs

One of the most important Pair RDD operations is joining. It’s especially useful when working with structured data, which we’ll discuss later. There are three types of join operations available: inner, left, and right. Note that joins are relatively expensive operations in Spark because they tend to move data around the cluster. This doesn’t mean that you shouldn’t use them at all, just be careful and expect longer processing times if you are joining really big data sets together. Here is the overview of join operations:

Table 6: Join operations

Transformation | Description |

join(otherDataset) | When called on datasets (K, V) and (K, W), it returns a dataset of (K, (V, W)) pairs with all pairs of elements for each key. |

leftOuterJoin(otherDataset) | When called on datasets (K, V) and (K, W), it returns a dataset with all pairs (K, (V, Some(W))). W is of type Optional, and we’ll show in our example how to work with Optionals. |

rightOuterJoin(otherDataset) | When called on datasets (K, V) and (K, W), it returns a dataset with all pairs (K, Some(V), W). V is of type Optional. |

We’ll continue with the used car market example when working with Pair RDDs. We’ll add information about car dealers to our previous dataset. Here is the dataset that we’re going to use for Scala and Python. We won’t go through every step for Java. For Java we’ll provide source code after Scala and Python examples. The data definition is as following:

Code Listing 74: Scala Used Cars and Dealers Example

case class UsedCar(dealer: String, year: Int, name: String, color: String) case class Dealer(dealer: String, name: String) val cars = List( UsedCar("a", 2012, "Honda Accord LX", "gray"), UsedCar("b", 2008, "Audi Q7 4.2 Premium", "white"), UsedCar("c", 2006, "Mercedes-Benz CLS-Class CLS500", "black"), UsedCar("a", 2012, "Mitsubishi Lancer", "black"), UsedCar("c", 2010, "BMW 3 Series 328i", "gray"), UsedCar("c", 2006, "Buick Lucerne CX", "gray"), UsedCar("c", 2006, "GMC Envoy", "red"), UsedCar("unknown", 2006, "GMC Envoy", "red") ) val carsByDealer = sc.parallelize(cars).map(x => (x.dealer, x)) val dealers = List( Dealer("a", "Top cars"), Dealer("b", "Local dealer"), Dealer("d", "Best cars") ) var dealersById = sc.parallelize(dealers).map(x => (x.dealer, x)) |

Code Listing 75: Python Used Cars and Dealers Example

cars = [ ("a", 2012, "Honda Accord LX", "gray"), ("b", 2008, "Audi Q7 4.2 Premium", "white"), ("c", 2006, "Mercedes-Benz CLS-Class CLS500", "black"), ("a", 2012, "Mitsubishi Lancer", "black"), ("c", 2010, "BMW 3 Series 328i", "gray"), ("c", 2006, "Buick Lucerne CX", "gray"), ("c", 2006, "GMC Envoy", "red"), ("unknown", 2006, "GMC Envoy", "red") ] cars_by_dealer = sc.parallelize(cars).map(lambda x: (x[0], x)) dealers = [ ("a", "Top cars"), ("b", "Local dealer"), ("d", "Best cars") ] dealers_by_id = sc.parallelize(dealers).map(lambda x: (x[0], x)) |

Now that we have defined our data, we can go over join operations in Scala and Python. Let’s start with regular inner join operation:

Code Listing 76: Scala Dealers and Cars Join Operation in Spark Shell

scala> carsByDealer.join(dealersById).foreach(println) (a,(UsedCar(a,2012,Honda Accord LX,gray),Dealer(a,Top cars))) (a,(UsedCar(a,2012,Mitsubishi Lancer,black),Dealer(a,Top cars))) (b,(UsedCar(b,2008,Audi Q7 4.2 Premium,white),Dealer(b,Local dealer))) |

Code Listing 77: Python Dealers and Cars Join Operation in PySpark

>>> cars_and_dealers_joined = cars_by_dealer.join(dealers_by_id) >>> >>> for x in cars_and_dealers_joined.collect(): ... print x[0] + ', ' + str(x[1][0][1]) + ', ' + x[1][0][2] + ', ' + x[1][1][1] ... a, 2012, Honda Accord LX, Top cars a, 2012, Mitsubishi Lancer, Top cars b, 2008, Audi Q7 4.2 Premium, Local dealer |

Join works by creating elements only if they are present on both sides. Sometimes we need to display information regardless of their presence on both sides. In that case we use left and right join. Here is an example of using leftOuterJoin:

Code Listing 78: Scala Dealers and Cars Left Outer Join Operation in Spark Shell

scala> carsByDealer.leftOuterJoin(dealersById).foreach(println) (b,(UsedCar(b,2008,Audi Q7 4.2 Premium,white),Some(Dealer(b,Local dealer)))) (unknown,(UsedCar(unknown,2006,GMC Envoy,red),None)) (c,(UsedCar(c,2006,Mercedes-Benz CLS-Class CLS500,black),None)) (c,(UsedCar(c,2010,BMW 3 Series 328i,gray),None)) (c,(UsedCar(c,2006,Buick Lucerne CX,gray),None)) (c,(UsedCar(c,2006,GMC Envoy,red),None)) (a,(UsedCar(a,2012,Honda Accord LX,gray),Some(Dealer(a,Top cars)))) (a,(UsedCar(a,2012,Mitsubishi Lancer,black),Some(Dealer(a,Top cars)))) |

Code Listing 79: Python Dealers and Cars Left Outer Join Operation in PySpark

cars_and_dealers_joined_left = cars_by_dealer.leftOuterJoin(dealers_by_id) for x in cars_and_dealers_joined_left.collect(): out = x[0] + ', ' + str(x[1][0][1]) + ', ' + x[1][0][2] + ', ' if x[1][1] is None: out += 'None' else: out += x[1][1][1] print out a, 2012, Honda Accord LX, Top cars a, 2012, Mitsubishi Lancer, Top cars unknown, 2006, GMC Envoy, None c, 2006, Mercedes-Benz CLS-Class CLS500, None c, 2010, BMW 3 Series 328i, None c, 2006, Buick Lucerne CX, None c, 2006, GMC Envoy, None b, 2008, Audi Q7 4.2 Premium, Local dealer |

Right joining would then look something like:

Code Listing 80: Scala Dealers and Cars Right Outer Join Operation in Spark Shell

scala> carsByDealer.rightOuterJoin(dealersById).foreach(println) (d,(None,Dealer(d,Best cars))) (b,(Some(UsedCar(b,2008,Audi Q7 4.2 Premium,white)),Dealer(b,Local dealer))) (a,(Some(UsedCar(a,2012,Honda Accord LX,gray)),Dealer(a,Top cars))) (a,(Some(UsedCar(a,2012,Mitsubishi Lancer,black)),Dealer(a,Top cars))) |

Code Listing 81: Python Dealers and Cars Right Outer Join Operation in Spark Shell

cars_and_dealers_joined_right = cars_by_dealer.rightOuterJoin(dealers_by_id) for x in cars_and_dealers_joined_right.collect(): out = x[0] + ', ' if x[1][0] is None: out += 'None' else: out += str(x[1][0][1]) + ', ' + x[1][0][2] + ', ' out += x[1][1][1] print out a, 2012, Mitsubishi Lancer, Top cars b, 2008, Audi Q7 4.2 Premium, Local dealer d, None, Best cars |

With Java, we are just going to have one big example with all the operations at the end. We’ll use code comments to mark every important block there. There are other important Pair RDD operations besides joins. One of them is intersection. Intersection is not defined as a separate operation on RDD, but it can be expressed by using other operations. Here is what it would look like in Scala:

Code Listing 82: Scala Dealers and Cars Intersection Operation in Spark Shell

scala> carsByDealer.groupByKey().join(dealersById.groupByKey()) (a,UsedCar(a,2012,Honda Accord LX,gray)) (b,UsedCar(b,2008,Audi Q7 4.2 Premium,white)) (b,Dealer(b,Local dealer)) (a,UsedCar(a,2012,Mitsubishi Lancer,black)) (a,Dealer(a,Top cars)) |

Code Listing 83: Python Dealers and Cars Intersection Operation in PySpark

cars_and_dealers_intersection = cars_by_dealer.groupByKey().join(dealers_by_id.groupByKey()).flatMapValues(lambda x: [x[0], x[1]]) for x in cars_and_dealers_intersection.collect(): for xi in x[1]: print x[0] + ', ' + str(xi[1]) + (', ' + xi[2] if len(xi) > 2 else '') a, 2012, Honda Accord LX a, 2012, Mitsubishi Lancer unknown, 2006, GMC Envoy c, 2006, Mercedes-Benz CLS-Class CLS500 c, 2010, BMW 3 Series 328i c, 2006, Buick Lucerne CX c, 2006, GMC Envoy b, 2008, Audi Q7 4.2 Premium |

Note that usually intersection, union, and difference are combined with the same type of data. The intent for previous examples was to demonstrate that everything remains flexible in Spark. That and combining real-life entities is better than joining some generic data like numbers. But if you try to call an actual union operator on two collections, you would get an error saying that the types are not compatible. Here is an example of the actual Spark Shell call:

Code Listing 84: Fail of Scala Dealers and Cars Union Operation in Spark Shell

scala> carsByDealer.union(dealersById).foreach(println) <console>:34: error: type mismatch; found : org.apache.spark.rdd.RDD[(String, Dealer)] required: org.apache.spark.rdd.RDD[(String, UsedCar)] carsByDealer.union(dealersById).foreach(println) |

To continue with the examples, we are going to define another group of cars. We will simply give suffix 2 to this group:

Code Listing 85: Scala Second Group of Cars

val cars2 = List( UsedCar("a", 2008, "Toyota Auris", "black"), UsedCar("c", 2006, "GMC Envoy", "red") ) val carsByDealer2 = sc.parallelize(cars2).map(x => (x.dealer, x)) |

Code Listing 86: Python Second Group of Cars

cars2 = [ ("a", 2008, "Toyota Auris", "black"), ("c", 2006, "GMC Envoy", "red") ] cars_by_dealer2 = sc.parallelize(cars2).map(lambda x: (x[0], x)) |

Now that we have the second group defined, we can have a look at what the union operation is doing:

Code Listing 87: Scala Union Operation Example

scala> carsByDealer.union(carsByDealer2).foreach(println) (c,UsedCar(c,2006,Mercedes-Benz CLS-Class CLS500,black)) (a,UsedCar(a,2012,Mitsubishi Lancer,black)) (a,UsedCar(a,2012,Honda Accord LX,gray)) (b,UsedCar(b,2008,Audi Q7 4.2 Premium,white)) (c,UsedCar(c,2010,BMW 3 Series 328i,gray)) (c,UsedCar(c,2006,Buick Lucerne CX,gray)) (c,UsedCar(c,2006,GMC Envoy,red)) (unknown,UsedCar(unknown,2006,GMC Envoy,red)) (a,UsedCar(a,2008,Toyota Auris,black)) (c,UsedCar(c,2006,GMC Envoy,red)) |

Code Listing 88: Python Union Operation Example

cars_union = cars_by_dealer.union(cars_by_dealer2) for x in cars_union.collect(): print str(x[0]) + ', ' + str(x[1][1]) + ', '+ x[1][2] b, 2008, Audi Q7 4.2 Premium c, 2006, Mercedes-Benz CLS-Class CLS500 a, 2012, Mitsubishi Lancer c, 2010, BMW 3 Series 328i c, 2006, Buick Lucerne CX c, 2006, GMC Envoy unknown, 2006, GMC Envoy a, 2008, Toyota Auris c, 2006, GMC Envoy |

The last operation that we are going to discuss is difference. Difference is computed by calling the subtractByKey operation:

Code Listing 89: Scala Difference Operation

scala> carsByDealer.subtractByKey(carsByDealer2).foreach(println) (b,UsedCar(b,2008,Audi Q7 4.2 Premium,white)) (unknown,UsedCar(unknown,2006,GMC Envoy,red)) |

Code Listing 90: Python Difference Operation

cars_difference = cars_by_dealer.subtractByKey(cars_by_dealer2) for x in cars_difference.collect(): print str(x[0]) + ', ' + str(x[1][1]) + ', '+ x[1][2] b, 2008, Audi Q7 4.2 Premium |

This completes the overview of operations between two Pair RDDs. The Java examples are much more verbose, so I decided to group them into one example to save code on initialization. Here is the Java version of code for the entire section.

Code Listing 91: Operations between Two Pair RDDs in Java

package com.syncfusion.succinctly.spark.examples; import java.io.Serializable; import java.util.Arrays; import java.util.List; import org.apache.spark.SparkConf; import org.apache.spark.api.java.JavaPairRDD; import org.apache.spark.api.java.JavaSparkContext; import org.apache.spark.api.java.function.PairFunction; import com.google.common.base.Optional; import scala.Tuple2; public class OperationsBetweenToPairRddsJava7 { public static class UsedCar implements Serializable { public String _dealer; public int _year; public String _name; public String _color; public UsedCar(String dealer, int year, String name, String color) { this._dealer = dealer; this._year = year; this._name = name; this._color = color; } @Override public String toString() { return _dealer + ", " + _year + ", " + _name + ", " + _color; } } public static class Dealer implements Serializable { public String _dealer; public String _name; public Dealer(String dealer, String name) { this._dealer = dealer; this._name = name; } @Override public String toString() { return _dealer + ", " + _name; } } public static void main(String[] args) throws Exception { if (args.length < 1) { System.err.println("Please provide a full path to the output file"); System.exit(0); } SparkConf conf = new SparkConf().setAppName("OperationsBetweenToPairRddsJava7").setMaster("local"); JavaSparkContext context = new JavaSparkContext(conf); List<UsedCar> cars = Arrays.asList( new UsedCar("a", 2012, "Honda Accord LX", "gray"), new UsedCar("b", 2008, "Audi Q7 4.2 Premium", "white"), new UsedCar("c", 2006, "Mercedes-Benz CLS-Class CLS500", "black"), new UsedCar("a", 2012, "Mitsubishi Lancer", "black"), new UsedCar("c", 2010, "BMW 3 Series 328i", "gray"), new UsedCar("c", 2006, "Buick Lucerne CX", "gray"), new UsedCar("c", 2006, "GMC Envoy", "red"), new UsedCar("unknown", 2006, "GMC Envoy", "red")); PairFunction<UsedCar, String, UsedCar> mapCars = new PairFunction<UsedCar, String, UsedCar>() { public Tuple2<String, UsedCar> call(UsedCar c) { return new Tuple2<String, UsedCar>(c._dealer, c); } }; JavaPairRDD<String, UsedCar> carsByDealer = context.parallelize(cars).mapToPair(mapCars); List<Dealer> dealers = Arrays.asList( new Dealer("a", "Top cars"), new Dealer("b", "Local dealer"), new Dealer("d", "Best cars") ); JavaPairRDD<String, Dealer> dealersById = context.parallelize(dealers) .mapToPair(new PairFunction<Dealer, String, Dealer>() { public Tuple2<String, Dealer> call(Dealer c) { return new Tuple2<String, Dealer>(c._dealer, c); } }); // join operation JavaPairRDD<String, Tuple2<UsedCar, Dealer>> carsAndDealersJoined = carsByDealer.join(dealersById); carsAndDealersJoined.saveAsTextFile(args[0] + "carsAndDealersJoined"); // left outer join operation JavaPairRDD<String, Tuple2<UsedCar, Optional<Dealer>>> carsAndDealersJoinedLeft = carsByDealer .leftOuterJoin(dealersById); carsAndDealersJoinedLeft.saveAsTextFile(args[0] + "carsAndDealersJoinedLeft"); // right outer join operation JavaPairRDD<String, Tuple2<Optional<UsedCar>, Dealer>> carsAndDealersJoinedRight = carsByDealer .rightOuterJoin(dealersById); carsAndDealersJoinedLeft.saveAsTextFile(args[0] + "carsAndDealersJoinedRight"); // intersection JavaPairRDD<String, Tuple2<Iterable<UsedCar>, Iterable<Dealer>>> carsAndDealersIntersection = carsByDealer .groupByKey().join(dealersById.groupByKey()); carsAndDealersJoinedLeft.saveAsTextFile(args[0] + "carsAndDealersIntersection"); List<UsedCar> cars2 = Arrays.asList(new UsedCar("a", 2008, "Toyota Auris", "black"), new UsedCar("c", 2006, "GMC Envoy", "red") ); JavaPairRDD<String, UsedCar> carsByDealer2 = context.parallelize(cars).mapToPair(mapCars); // union JavaPairRDD<String, UsedCar> carsUnion = carsByDealer.union(carsByDealer2); carsUnion.saveAsTextFile(args[0] + "carsUnion"); // difference JavaPairRDD<String, UsedCar> carsDifference = carsByDealer.subtractByKey(carsByDealer2); carsUnion.saveAsTextFile(args[0] + "carsDifference"); } } |

As practice for this section, you can go to the output directory that you specified when running the submit task for this example and have a look at the output files. See if you can notice anything interesting.

In this section we went over the operations between two Pair RDDs in Spark. It’s a very important subject when doing distributed computing and processing data with Spark. This concludes the chapter about Spark’s internal mechanism. In the next chapter we are going to discuss how Spark acquires the data, and we’ll focus on how to deliver results data to channels other than text files and interactive shells.

- 1800+ high-performance UI components.

- Includes popular controls such as Grid, Chart, Scheduler, and more.

- 24x5 unlimited support by developers.