CHAPTER 7

Interface Segregation Principle

Let’s again look at a definition from wikipedia:

"No client should be forced to depend on methods that it does not use. ISP splits interfaces that are very large into smaller and more specific ones."

I take this to mean: "As a client, why should I implement nine methods of an interface when I need only three methods?" Fewer methods make a developer’s life easier.

You might notice that this is similar to the High Cohesion Principle of General Responsibility Assignment Software Patterns (GRASP). Although GRASP goes beyond the scope of this e-book, we should be aware that these patterns provide a guide for assigning responsibility to collaborating objects.

Here is a list of the GRASP patterns:

- Creator

- Information Expert

- Low Coupling

- Controller

- High Cohesion

- Indirection

- Polymorphism

- Protected Variables

- Pure Fabrication

Note: ‘Cohesion’ refers to how the operations of any element are functionally related.

Note: Refer to: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cohesion_(computer_science) to learn more about Cohesion.

In previous chapters, we’ve seen how to solve our validators issue. For the proper solution, we adopt ISP. Can we say that if someone is violating LSP, they gain an understanding of ISP?

In this chapter we will discuss a few more scenarios in which we can adapt ISP to solve our real-world problems.

Here’s what Robert C. Martin said about ISP:

From this, we can say that we should not mess classes in a pollution of interfaces. Our implementing class should obey the interface that possesses the required functionality.

Let me rephrase—ISP says we should not force clients to use interfaces they don’t need to use.

Let’s go back and revisit the problem in which one of our validators didn’t want to use a specific method, but we forced it to use our IsValid() method.

Code Listing 32

public interface IValidator { void Load(); bool Isvalid(); } |

Here in Code Listing 32 we are providing the interface IValidator for the client. Note that if any class implements this interface, it must implement all the methods.

If one class doesn’t need either the Load() or the IsValid() method, this interface is forcing clients to implement unwanted methods, as Code Listing 33 demonstrates.

Code Listing 33

public class DynamicValidator : IValidator { public bool IsValid() { //I do not want this, why should I care about this? throw new NotImplementedException(); } public void Load() { //Some stuff } } |

DynamicValidator is not meant to implement the IsValid() method. If a client implements IValidator, that client is forced to deal with the IsValid() method, which is not good. If you are doing this, your client won’t be happy.

In other words, we can say that our interface IValidator is fat and not cohesive. It might have only two methods, but most clients will feel uneasy interacting with these methods.

Note: An interface is called a fat interface or a bloated interface when it incorporates too many operations. Refer to: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Interface_bloat for more details.

Many developers get confused while they’re reading about LSP and ISP. Here is a concise statement of the difference between them:

With that in mind, we’ll look into the implementation logic for ISP. In Code Listing 34, we have an abstract class validator.

Code Listing 34

public abstract class Validator { public abstract void Load(); public abstract bool IsValid(); } |

Some clients will implement this class in order to implement client-specific business logics or what they need as per their own requirements. Code Listing 35 shows an example.

Code Listing 35

public class SchemaValidator : Validator { public override bool IsValid() { throw new NotImplementedException(); } public override void Load() { throw new NotImplementedException(); } } |

And we have a DynamicValidator as well, as seen in Code Listing 36.

Code Listing 36

public class DynamicValidator : Validator { public override bool IsValid() { throw new NotImplementedException(); } public override void Load() { throw new NotImplementedException(); } } |

Note: This is not complete code. Refer to Bitbucket for the complete source code.

In Code Listing 36’s scenario, all clients have to bind or must stick with the internal implementation, which means they have to override the methods declared in the abstract class.

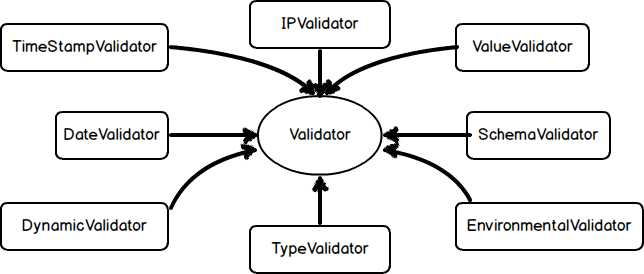

Figure 9: 1-server, n-clients scenario

In Figure 9, we have a scenario in which 1-server is contacted by n-number of clients. We have certain clients that are a special type of client, such as DynamicValidator and EnvironmentalValidator (these require either method).

You can also think in terms of vice-versa. Suppose you have an interface, IValidator, that has only the IsValid() method, and various clients are using this. Some special type of validators require one additional method along with IsValid(). This new method would be Notify(). Here is the challenge—if we add a new method to an existing interface, we are forcing our happy clients to implement new methods as well.

Imagine you are using an API from a third party, you implement everything, then you deploy to production. The next day, when you come into the office, you are suddenly informed that the third party changed its API and added a new method to the interface you are currently using. Whichever programmers changed that API, you hope their cell phone falls in a toilet!

So you can see how painful it would be if you put unnecessary methods in the interfaces and forced a client to use them. Yet in this scenario, the client must use them because there is no other option available.

Imagine a case in which your implementations team is very happy with the external clients who are using your interfaces, but suddenly your manager says that a top revenue-generating client has requested a few changes be made in your existing interface. They want to add two new methods and delete or deprecate one old method (as they are not going to use it anymore). What would you do?

As a typical developer, you would start digging into the code, or you would discuss the situation with your manager and come up with some good solutions. There are a lot of headaches in real-world applications while you are working with highly scalable applications and your clients are pushing you to provide them new features continuously.

Let’s come back to our original issue of interface segregation. We have the solution, but there are a few more tweaks I would like to discuss.

What is our requirement?

As clients, we must implement only those things we require. As module writers, we should not force our client to implement anything they might not require.

In our real-time example, we must provide a new method to both our old and new clients, so let’s try to make it ISP in Code Listing 37.

Code Listing 37

public interface IValidator { bool Isvalid(); } public interface IvalidatorLoader : IValidator { void Load(); } |

In order to meet our requirements, we have created a new interface IValidatorLoader, which implements interface IValidator itself. Why? Because our new clients need new methods, but they don’t say whether or not they still require the existing method, which means they will get both the old and new methods, IsValid() and Load(), as seen in Code Listing 38.

Code Listing 38

public class Validator : IValidator { public bool Isvalid() { //Perform some awesome stuff here. return true; } } |

Our old validator class will remain unchanged—it will implement IValidator interface and there will be no change in business logic, either.

Code Listing 39

public class SpecialValidator : IValidator, IvalidatorLoader { public bool Isvalid() { //Why should I do new things—I have this method already in place. Validator validator = new Validator(); return validator.Isvalid(); } public void Load() { //Perform good stuff here to load special validator. } } |

Code Listing 39 shows our SpecialValidator class, which is introduced in order to meet the requirements of our new clients. The new class implements both IValidator and IValidatorLoader.

There are no changes in business logic for our IsValid() method—we are simply wiring up the existing method within definition. There is no need to write and make duplicate code.

Note that we have introduced a new Load() method. It should have some real business logic, and here we write all business logics related to our new Load() method.

We are done! Let’s see how our clients will be making a call as depicted in Code Listing 40.

Code Listing 40

class Program { static void Main(string[] args) { Console.WriteLine("Old clients, who do not require a new method"); IValidator validator = new Validator(); var isvalid = validator.Isvalid(); NotifyValidationStuff(isvalid); IvalidatorLoader validatorLoader = new SpecialValidator(); NotifyValidationStuff(validatorLoader.Isvalid()); //This is for example only, in real time one should have some business logic on when to load validators. validatorLoader.Load(); Console.WriteLine("New client can get the taste of Load() method as well"); Console.ReadLine(); } private static void NotifyValidationStuff(bool isvalid) { Console.WriteLine("Validations are {0}.", isvalid ? "passing" : "failing"); } } |

This is what we wanted. Code Listing 40’s code is self-explanatory. We keep our old clients happy by not complicating their lives, and we provide good things for our new clients, giving them access to both the new and old methods.

- 1800+ high-performance UI components.

- Includes popular controls such as Grid, Chart, Scheduler, and more.

- 24x5 unlimited support by developers.