CHAPTER 4

Combinatorics

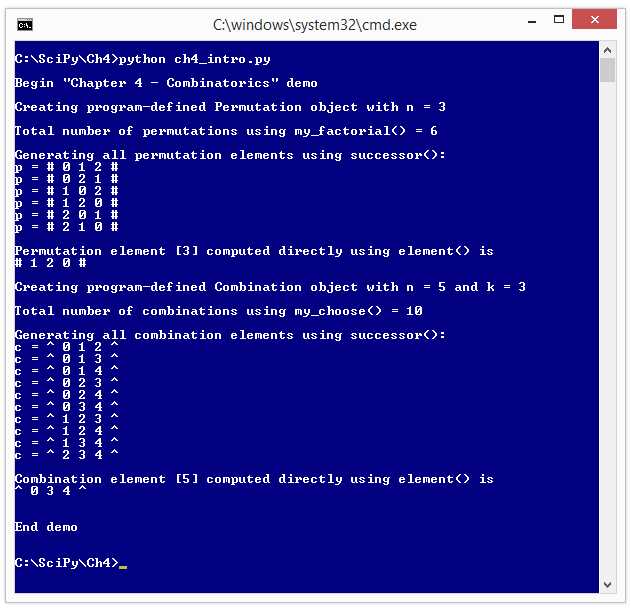

Combinatorics is a branch of mathematics dealing with permutations (rearrangements of items) and combinations (subsets of items). Python has limited support for combinatorics in the itertools and scipy modules, but you can create combinatorics functions using NumPy arrays and matrices. The following screenshot shows you where this chapter is headed.

Figure 24: Combinatorics Demo

In section 4.1, you'll learn how to create a program-defined Permutation class using NumPy, and how to write an effective factorial function.

In section 4.2, you'll learn how to write a successor() function that returns the next permutation element in lexicographical order.

In section 4.3, you'll learn how to create a useful element() function that directly generates a specified permutation element.

In section 4.4, you'll learn how to create a Combination class.

In section 4.5, you'll learn how to write a Combination successor() function.

And in section 4.6, you'll learn how to write an element() function for combinations.

4.1 Permutations

A mathematical permutation set is all possible orderings of n items. For example, if n = 3 and the items are the integers (0, 1, 2) then there are six possible permutation elements:

(0, 1, 2)

(0, 2, 1)

(1, 0, 2)

(1, 2, 0)

(2, 0, 1)

(2, 1, 0)

Python supports permutations in the SciPy special module and in the Python itertools module. Interestingly, NumPy has no direct support for permutations, but it is possible to implement custom permutation functions using NumPy arrays.

Code Listing 14: Permutations Demo

# permutations.py # Python 2.7 import numpy as np import itertools as it import scipy.special as ss class Permutation: def __init__(self, n): self.n = n self.data = np.arange(n) @staticmethod def my_fact(n): ans = 1 for i in xrange(1, n+1): ans *= i return ans def as_string(self): s = "# " for i in xrange(self.n): s = s + str(self.data[i]) + " " s = s + "#" return s # ===== print "\nBegin permutation demo \n" n = 3 print "Setting n = " + str(n) print "" num_perms = ss.factorial(n) print "Using scipy.special.factorial(n) there are ", print str(num_perms), print "possible permutation elements" print "" print "Making all permutations using itertools.permutations()" all_perms = it.permutations(xrange(n)) p = all_perms.next() print "The first itertools permutation is " print p print "" num_perms = Permutation.my_fact(n) print "Using my_fact(n) there are " + str(num_perms), print "possible permutation elements" print "" print "Making a custom Permutation object " p = Permutation(n) print "The first custom permutation element is " print p.as_string() print "\nEnd demo \n" |

C:\SciPy\Ch4> python permutations.py Setting n = 3 Using scipy.special.factorial(n) there are 6.0 possible permutation elements Making all permutations using itertools.permutations() The first itertools permutation is (0, 1, 2) Using my_fact(n) there are 6 possible permutation elements Making a custom Permutation object The first custom permutation element is # 0 1 2 # End demo |

The demo program begins by importing three modules:

import numpy as np

import itertools as it

import scipy.special as ss

The itertools module has the primary permutations class, but the closely associated factorial() function is defined in the special submodule of the scipy module. If this feels a bit awkward to you, you're not alone.

The demo program defines a custom Permutation class. In most cases, you will only want to define a custom implementation of a function when you need to implement some specialized behavior, or you want to avoid using a module that contains the function.

Program execution begins by setting up the number of permutation elements:

n = 3

print "Setting n = " + str(n)

Using lowercase n for the number of permutations is traditional, so you should use it unless you have a reason not to. Next, the demo program determines the number of possible permutations using the SciPy factorial() function:

num_perms = ss.factorial(n)

print "Using scipy.special.factorial(n) there are ",

print str(num_perms),

print "possible permutation elements"

The factorial(n) function is often written as n! as a shortcut. The factorial of a number is best explained by example:

factorial(3) = 3 * 2 * 1 = 6

factorial(5) = 5 * 4 * 3 * 2 * 1 = 120

The value of factorial(0) is usually considered a special case and defined to be 1. Next, the demo creates a Python permutations iterator:

all_perms = it.permutations(xrange(n))

I like to think of a Python iterator object as a little factory that can emit data when a request is made of it using an explicit or implicit call to a next() function. Notice the call to the permutations() function accepts xrange(n) rather than just n, as you might have thought.

The demo program requests and displays the first itertools permutation element like so:

p = all_perms.next()

print "The first itertools permutation is "

print p

Next, the demo program uses the custom functions. First, the my_fact() function is called:

num_perms = Permutation.my_fact(n)

print "Using my_fact(n) there are " + str(num_perms),

print "possible permutation elements"

Notice that the call to my_fact() is appended to Permutation, which is the name of its defining class. This is because the my_fact() function is decorated with the @staticmethod attribute.

Next, the demo creates an instance of the custom Permutation class. The Permutation class __init__() constructor method initializes an object to the first permutation element so there's no need to call a next() function:

p = Permutation(n)

print "The first custom permutation element is "

print p.as_string()

The custom as_string() function displays a Permutation element delimited by the % character so that the element can be easily distinguished from a tuple, a list, or another Python collection. I used % because both permutation and percent start with the letter p.

The custom my_fact() function is short and simple:

def my_fact(n):

ans = 1

for i in xrange(1, n+1):

ans *= i

return ans

The mathematical factorial function is often used in computer science classes as an example of a function that can be implemented using recursion:

@staticmethod

def my_fact_rec(n):

if n == 0 or n == 1:

return 1

else:

return n * Permutation.my_fact_rec(n-1)

Although recursion has a certain mysterious aura, in most situations (such as this one), recursion is highly inefficient and so should be avoided.

An option for any implementation of a factorial function, especially where the function will be called many times, is to create a pre-calculated lookup table with values for the first handful (say 1,000) results. The extra storage is usually a small price to pay for much-improved performance.

Resources

For details about the Python itertools module that contains the permutations iterator, see

https://docs.python.org/2/library/itertools.html.

For details about the SciPy factorial() function, see

http://docs.scipy.org/doc/scipy-0.16.1/reference/generated/scipy.misc.factorial.html.

For information about mathematical permutations, see

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Permutation.

4.2 Permutation Successor

When working with mathematical permutations, a key operation is generating the successor to a given permutation element. For example, if n = 3 and the items are the integers (0, 1, 2) then there are six possible permutation elements. When listed in what is called lexicographical order, the elements are:

(0, 1, 2)

(0, 2, 1)

(1, 0, 2)

(1, 2, 0)

(2, 0, 1)

(2, 1, 0)

Notice that if we removed the separating commas and interpreted each element as an ordinary integer (like 120), the elements would be in ascending order (12 < 21 < 102 < 120 < 201 < 210).

Code Listing 15: Permutation Successor Demo

# perm_succ.py # Python 2.7 import numpy as np import itertools as it class Permutation: def __init__(self, n): self.n = n self.data = np.arange(n) def as_string(self): s = "# " for i in xrange(self.n): s = s + str(self.data[i]) + " " s = s + "#" return s def successor(self): res = Permutation(self.n) # result res.data = np.copy(self.data) left = self.n - 2 while res.data[left] > res.data[left+1] and left >= 1: left -= 1 if left == 0 and res.data[left] > res.data[left+1]: return None right = self.n - 1 while res.data[left] > res.data[right]: right -= 1 res.data[left], res.data[right] = \ res.data[right], res.data[left] i = left + 1 j = self.n - 1 while i < j: tmp = res.data[i] res.data[i] = res.data[j] res.data[j] = tmp i += 1; j -= 1 return res # ===== print "\nBegin permutation successor demo \n" n = 3 print "Setting n = " + str(n) print "" perm_it = it.permutations(xrange(n)) print "Iterating all permutations using itertools permutations(): " for p in perm_it: print "p = " + str(p) print ""

p = Permutation(n) print "Iterating all permutations using custom Permutation class: " while p is not None: print "p = " + p.as_string() p = p.successor() print "\nEnd demo \n" |

C:\SciPy\Ch4> python perm_succ.py Setting n = 3 Iterating all permutations using itertools permutations(): p = (0, 1, 2) p = (0, 2, 1) p = (1, 0, 2) p = (1, 2, 0) p = (2, 0, 1) p = (2, 1, 0) Iterating all permutations using custom Permutation class: p = # 0 1 2 # p = # 0 2 1 # p = # 1 0 2 # p = # 1 2 0 # p = # 2 0 1 # p = # 2 1 0 # End demo |

The demo program begins by importing two modules:

import numpy as np

import itertools as it

Since the itertools module has many kinds of iterable objects, an alternative is to bring just the permutations iterator into scope:

from itertools import permutations

The demo program defines a custom Permutation class. In most cases, you will only want to define a custom implementation of a function when you need to implement some specialized behavior, or you want to avoid using a module that contains the function.

Program execution begins by setting up the number of permutation elements:

n = 3

print "Setting n = " + str(n)

Using lowercase n for the number of permutations is traditional, so you should use it unless you have a reason not to.

Next, the demo program iterates through all possible permutation elements using an implicit mechanism:

perm_it = permutations(xrange(n))

print "Iterating all permutations using itertools permutations(): "

for p in perm_it:

print "p = " + str(p)

print ""

The perm_it iterator can emit all possible permutation elements. In most situations, Python iterators are designed to be called using a for item in iterator pattern, as shown. In other programming languages, this pattern is sometimes distinguished from a regular for loop by using a foreach keyword.

Note that the itertools.permutations() iterator emits tuples, indicated by the parentheses in the output, rather than a list or a NumPy array.

It is possible, but somewhat awkward, to explicitly call the permutations iterator using the next() function like so:

perm_it = it.permutations(xrange(n))

while True:

try:

p = perm_it.next()

print "p = " + str(p)

except StopIteration:

break

print ""

By design, iterator objects don't have an explicit way to signal the end of iteration, such as an end() function or returning a special value like None. Instead, when an iterator object has no more items to emit and a call to next() is made, a StopIteration exception is thrown. To terminate a loop, you must catch the exception.

Next, the demo program iterates through all permutation elements for n = 3 using the program-defined Permutation class:

p = Permutation(n)

print "Iterating all permutations using custom Permutation class: "

while p is not None:

print "p = " + p.as_string()

p = p.successor()

The successor() function of the Permutation class uses a traditional stopping technique by returning None when there are no more permutation elements. The function successor() uses an unobvious approach to determine when the current permutation element is the last one. A straightforward approach isn't efficient. For example, if n = 5, the last element is (4 3 2 1 0) and it'd be very time-consuming to check if data[0] > data[1] > data[2] > . . > data[n-1] on each call.

The logic in the program-defined successor() function is rather clever. Suppose n = 5 and the current permutation element is:

# 0 1 4 3 2 #

The next element in lexicographical order after 01432, using the digits 0 through 4, is 02134. The successor() function first finds the indices of two items to swap, called left and right. In this case, left = 1 and right = 4. The items at those indices are swapped, giving a preliminary result of 02431. Then the items from index right through the end of the element are placed in order (431 in this example) giving the final result of 02134.

Resources

For details about the Python itertools module and the permutations iterator, see

https://docs.python.org/2/library/itertools.html.

The itertools.permutations iterator uses the Python yield mechanism. See

https://docs.python.org/2/reference/simple_stmts.html#yield.

4.3 Permutation Element

When working with mathematical permutations, it's often useful to be able to generate a specific element. For example, if n = 3 and the items are the integers (0, 1, 2), then there are six permutation elements. When listed in lexicographical order, the elements are:

[0] (0, 1, 2)

[1] (0, 2, 1)

[2] (1, 0, 2)

[3] (1, 2, 0)

[4] (2, 0, 1)

[5] (2, 1, 0)

In many situations, you want to iterate through all possible permutations, but in some cases you may want to generate just a specific permutation element. For example, a function call like pe = perm_element(4) would store (2, 0, 1) into pe.

Code Listing 16: Generating a Permutation Element Directly

# perm_elem.py # Python 2.7 import numpy as np import itertools as it import time class Permutation: def __init__(self, n): self.n = n self.data = np.arange(n) def as_string(self): s = "# " for i in xrange(self.n): s = s + str(self.data[i]) + " " s = s + "#" return s def element(self, idx): result = Permutation(self.n)

factoradic = np.zeros(self.n) for j in xrange(1, self.n + 1): factoradic[self.n-j] = idx % j idx = idx / j for i in xrange(self.n): factoradic[i] += 1 result.data[self.n - 1] = 1 for i in xrange(self.n - 2, -1, -1): result.data[i] = factoradic[i] for j in xrange(i + 1, self.n): if result.data[j] >= result.data[i]: result.data[j] += 1 for i in xrange(self.n): result.data[i] -= 1 return result; # ===== def perm_element(n, idx): p_it = it.permutations(xrange(n)) i = 0 for p in p_it: if i == idx: return p break i += 1 # ===== print "\nBegin permutation element demo \n" n = 20 print "Setting n = " + str(n) + "\n" idx = 1000000000 print "Element " + str(idx) + " using itertools.permutations() is " start_time = time.clock() pe = perm_element(n, idx) end_time = time.clock() elapsed_time = end_time - start_time print pe print "Elapsed time = " + str(elapsed_time) + " seconds " print "" p = Permutation(n) start_time = time.clock() pe = p.element(idx) end_time = time.clock() elapsed_time = end_time - start_time print "Element " + str(idx) + " using custom Permutation class is " print pe.as_string() print "Elapsed time = " + str(elapsed_time) + " seconds " print "" print "\nEnd demo \n" |

C:\SciPy\Ch4> python perm_elem.py Setting n = 20 Element 1000000000 using itertools.permutations() is (0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 9, 8, 7, 15, 17, 14, 16, 19, 11, 13, 18, 10, 12) Elapsed time = 162.92199766 seconds Element 1000000000 using custom Permutation class is # 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 9 8 7 15 17 14 16 19 11 13 18 10 12 # Elapsed time = 0.000253287676799 seconds End demo |

The demo program begins by importing three modules:

import numpy as np

import itertools as it

import time

The demo program defines a custom Permutation class that has an element() member function and a stand-alone function perm_element() that is not part of a class. Both functions return a specific permutation element. Function perm_element() uses the built-in permutations() iterator from the itertools module. Function element() uses a NumPy array plus a clever algorithm that involves something called the factoradic. Program execution begins by setting up the order of a permutation, n:

n = 20

print "Setting n = " + str(n) + "\n"

The order of a permutation is the number of items in each permutation. For n = 20 there are 20! = 2,432,902,008,176,640,000 different permutation elements. Next, the demo finds the permutation element 1,000,000,000 using the program-defined perm_element() function:

print "Element " + str(idx) + " using itertools.permutations() is "

start_time = time.clock()

pe = perm_element(n, idx)

end_time = time.clock()

After the permutation element has been computed, the element and the elapsed time required are displayed:

elapsed_time = end_time - start_time

print pe

print "Elapsed time = " + str(elapsed_time) + " seconds "

In this example, the perm_element() function took over 2 and a half minutes to execute. Not very good performance.

Next, the demo computes the same permutation element using the program-defined Permutation class:

p = Permutation(n)

start_time = time.clock()

pe = p.element(idx)

end_time = time.clock()

Then the element and the elapsed time required are displayed using the custom class approach:

elapsed_time = end_time - start_time

print "Element " + str(idx) + " using custom Permutation class is "

print pe.as_string()

print "Elapsed time = " + str(elapsed_time) + " seconds "

The elapsed time using the custom Permutation element() function class was approximately 0.0003 seconds—much better performance than the 160+ seconds for the itertools-based function.

It really wasn't a fair fight. The perm_element() function works by creating an itertools. permutations iterator and then generating each successive permutation one at a time until the desired permutation element is reached. The function definition is:

p_it = it.permutations(xrange(n)) # make a permutation iterator

i = 0 # index counter

for p in p_it: # request next permutation

if i == idx: # are we there yet?

return p # if so, return curr permutation tuple

break # and break out of loop

i += 1 # next index

On the other hand, the custom element() function uses some very clever mathematics and an entity called the factoradic of a number to construct the requested permutation element directly.

The regular decimal representation of numbers is based on powers of 10. For example, 1047 is (1 * 10^3) + (0 * 10^2) + (4 * 10^1) + (7 * 10^0). The factoradic of a number is an alternate representation based on factorials. For example, 1047 is 1232110 because it's (1 * 6!) + (2 * 5!) + (3 * 4!) + (2 * 3!) + (1 * 2!) + (1 * 1!) + (0 * 0!). Using some rather remarkable mathematics, it's possible to use the factoradic of a permutation element index to compute the element directly.

Resources

For details about the Python itertools module, which contains the permutations iterator, see

https://docs.python.org/2/library/itertools.html.

For information about mathematical factoradics, see

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Factorial_number_system.

4.4 Combinations

A mathematical combination set is a collection of all possible subsets of k items selected from n items. For example, if n = 5 and k = 3 and the items are the integers (0, 1, 2, 3, 4), then there are 10 possible combination elements:

(0, 1, 2)

(0, 1, 3)

(0, 1, 4)

(0, 2, 3)

(0, 2, 4)

(0, 3, 4)

(1, 2, 3)

(1, 2, 4)

(1, 3, 4)

(2, 3, 4)

For combinations, the order of the items does not matter. Therefore, there is no element (0, 2, 1) because it is considered the same as (0, 1, 2). Python supports combinations in the SciPy special module and in the Python itertools module. There is no direct support for combinations in SciPy, but it's possible to implement combination functions using NumPy arrays.

Code Listing 17: Combinations Demo

# combinations.py # Python 2.7 import numpy as np import itertools as it import scipy.special as ss class Combination: # n == order, k == subset size def __init__(self, n, k): self.n = n self.k = k self.data = np.arange(self.k) def as_string(self): s = "^ " for i in xrange(self.k): s = s + str(self.data[i]) + " " s = s + "^" return s @staticmethod def my_choose(n,k): if n < k: return 0 if n == k: return 1;

delta = k imax = n - k if k < n-k: delta = n-k imax = k ans = delta + 1 for i in xrange(2, imax+1): ans = (ans * (delta + i)) / i return ans # ===== print "\nBegin combinations demo \n" n = 5 k = 3 print "Setting n = " + str(n) + " k = " + str(k) print "" num_combs = ss.comb(n, k) print "n choose k using scipy.comb() is ", print num_combs print "" print "Making all combinations using itertools.combinations() " all_combs = it.combinations(xrange(n), k) c = all_combs.next() print "First itertools combination element is " print c print "" num_combs = Combination.my_choose(n, k) print "n choose k using my_choose(n, k) is ", print num_combs print "" print "Making a custom Combination object " c = Combination(n, k) print "The first custom combination element is " print c.as_string() print "\nEnd demo \n" |

C:\SciPy\Ch4> python combinations.py Setting n = 5 k = 3 n choose k using scipy.comb() is 10.0 Making all combinations using itertools.combinations() First itertools combination element is (0, 1, 2) n choose k using my_choose(n, k) is 10 Making a custom Combination object The first custom combination element is ^ 0 1 2 ^ End demo |

The demo program begins by importing three modules:

import numpy as np

import itertools as it

import scipy.special as ss

The itertools module has the primary combinations class, but the closely associated comb() function is defined in the special submodule of the scipy module (and also in scipy.misc).

The demo program defines a custom Combination class. In most cases, you will only want to define a custom implementation of a function when you need to implement some specialized behavior, or you want to avoid using a module that contains the function.

Program execution begins by setting up the number of items n, and the subset size k:

n = 5

k = 3

print "Setting n = " + str(n) + " k = " + str(k)

Lowercase n and k are most often used with combinations, so if you use different variable names it would be a good idea to comment on which is the number of items and which is the subset size. Next, the demo program determines the number of possible combination elements using the SciPy comb() function:

num_combs = ss.comb(n, k)

print "n choose k using scipy.comb() is ",

print num_combs

The function that returns the number of ways to select k items from n items is almost universally called choose(n, k) so it's not clear why the SciPy code implementation is named comb(n, k). The mathematical definition of choose(n, k) is n! / k! * (n-k)! where ! is the factorial function. For example:

choose(5, 3) = 5! / (3! * 2!) = 120 / (6 * 2) = 10

As it turns out, a useful fact is that choose(n, k) = choose(n, n-k). For example, choose(10, 7) = choose(10, 3). The choose function is easier to calculate using smaller values of the subset size.

Next, the demo creates a Python combinations iterator:

all_combs = it.combinations(xrange(n), k)

I like to think of a Python iterator object as a little factory that can emit data when a request is made of it using an explicit or implicit call to a next() function. Notice the call to the it.combinations() function accepts xrange(n) rather than just n. The choice of the name all_combs could be somewhat misleading if you're not familiar with Python iterators. The all_combs iterator doesn't generate all possible combination elements when it is created. It does, however, have the ability to emit all combination elements.

In addition to xrange(), the it.combinations() iterator can accept any iterable object. For example:

all_combs = it.combinations(np.array(["a", "b", "c"]), k)

Next, the demo program requests and displays the first itertools combination element like so:

c = all_combs.next()

print "The first itertools combination element is "

print c

Next, the demo program demonstrates the custom functions. First, the program-defined my_choose() function is called:

num_combs = Combination.my_choose(n, k)

print "n choose k using my_choose(n, k) is ",

print num_combs

Notice that the call to my_choose() is appended to Combination, which is the name of its defining class. This is because the my_choose() function is decorated with the @staticmethod attribute.

Next, the demo creates an instance of the custom Combination class. The Combination class __init__() constructor method initializes an object to the first combination element, so there's no need to call a next() function to get the first element:

print "Making a custom Combination object "

c = Combination(n, k)

print "The first custom combination element is "

print c.as_string()

The custom as_string() function displays a Combination element delimited by the ^ (carat) character so that the element can be easily distinguished from a tuple, a list, or another Python collection. I used ^ because both combination and carat start with the letter c.

The custom my_choose() function is rather subtle. It would be a weak approach to implement a choose function directly using the math definition because that would involve the calculation of three factorial functions. The factorial of a number can be very large. For example, 20! is 2,432,902,008,176,640,000 and 1000! is an almost unimaginably large number.

The my_choose() function uses a clever alternate definition that is best explained by example:

choose(10, 7) = choose(10, 3) = (10 * 9 * 8) / (3 * 2 * 1) = 120

Expressed in words, to calculate a choose(n, k) value, first simplify k to an equivalent smaller k if possible. Then the result is a division with k! on the bottom and n * n-1 * n-2 * . . * (n-k+1) on the top.

Furthermore, the top and bottom parts of the division don't have to be computed fully. Instead, the product of each pair of terms in the top can be iteratively divided by a term in the bottom. For example:

choose(10, 3) = 10 * 9 / 3 = 30 * 8 / 2 = 120

The implementation of my_choose() is presented in Code Listing 18.

Code Listing 18: Program-Defined Choose() Function

def my_choose(n, k): if n < k: return 0 if n == k: return 1; delta = k imax = n - k if k < n-k: delta = n-k imax = k ans = delta + 1 for i in xrange(2, imax+1): ans = (ans * (delta + i)) / i return ans |

The first two statements look for early exit conditions. The statements with delta and imax simplify k if possible. The for loop performs the iterated pair-multiplication and division.

Resources

For details about the Python itertools module that contains the combinations iterator, see

https://docs.python.org/2/library/itertools.html.

For details about the SciPy factorial() function, see

http://docs.scipy.org/doc/scipy-0.14.0/reference/generated/scipy.misc.comb.html.

4.5 Combination Successor

When working with mathematical combinations, a key operation is generating the successor to a given combination element. For example, if n = 5, k = 3, and the n items are the integers (0, 1, 2, 3, 4), then there are 10 possible combination elements. When listed in lexicographical order, the elements are:

(0, 1, 2)

(0, 1, 3)

(0, 1, 4)

(0, 2, 3)

(0, 2, 4)

(0, 3, 4)

(1, 2, 3)

(1, 2, 4)

(1, 3, 4)

(2, 3, 4)

Notice that if we removed the separating commas and interpreted each element as an ordinary integer (like 124), the elements would be in ascending order (12 < 13 < 14 < 23 < . . < 234).

Code Listing 19: Combinations Successor Demo

# comb_succ.py # Python 2.7 import numpy as np import itertools as it class Combination: # n == order, k == subset size

def __init__(self, n, k): self.n = n self.k = k self.data = np.arange(self.k) def as_string(self): s = "^ " for i in xrange(self.k): s = s + str(self.data[i]) + " " s = s + "^" return s def successor(self): if self.data[0] == self.n - self.k: return None

res = Combination(self.n, self.k) for i in xrange(self.k): res.data[i] = self.data[i] i = self.k - 1 while i > 0 and res.data[i] == self.n - self.k + i: i -= 1 res.data[i] += 1 for j in xrange(i, self.k - 1): res.data[j+1] = res.data[j] + 1 return res # ===== print "\nBegin combination successor demo \n" n = 5 k = 3 print "Setting n = " + str(n) + " k = " + str(k) print "" print "Iterating through all elements using itertools.combinations()" comb_iter = it.combinations(xrange(n), k) for c in comb_iter: print "c = " + str(c) print "" print "Iterating through all elements using custom Combination class" c = Combination(n, k) while c is not None: print "c = " + c.as_string() c = c.successor() print "" print "\nEnd demo \n" |

C:\SciPy\Ch4> python comb_succ.py Setting n = 5 k = 3 Iterating through all elements using itertools.combinations() c = (0, 1, 2) c = (0, 1, 3) c = (0, 1, 4) c = (0, 2, 3) c = (0, 2, 4) c = (0, 3, 4) c = (1, 2, 3) c = (1, 2, 4) c = (1, 3, 4) c = (2, 3, 4) Iterating through all elements using custom Combination class c = ^ 0 1 2 ^ c = ^ 0 1 3 ^ c = ^ 0 1 4 ^ c = ^ 0 2 3 ^ c = ^ 0 2 4 ^ c = ^ 0 3 4 ^ c = ^ 1 2 3 ^ c = ^ 1 2 4 ^ c = ^ 1 3 4 ^ c = ^ 2 3 4 ^ End demo |

The demo program begins by importing two modules:

import numpy as np

import itertools as it

Since the itertools module has many kinds of iterable objects, an alternative is to bring just the permutations iterator into scope:

from itertools import combinations

The demo program defines a custom Combination class. In most cases, you will only want to define a custom implementation of a function when you need to implement some specialized behavior, or you want to avoid using a module that contains the function (such as itertools).

Program execution begins by setting up the number of items and the subset size:

n = 5

k = 3

print "Setting n = " + str(n) + " k = " + str(k)

It is customary to use n and k when working with mathematical combinations, so you should do so unless you have a reason to use different variable names.

Next, the demo program iterates through all possible combination elements using an implicit mechanism:

print "Iterating through all elements using itertools.combinations()"

comb_iter = it.combinations(xrange(n), k)

for c in comb_iter:

print "c = " + str(c)

print ""

The comb_iter iterator can emit all possible combination elements. In most situations, Python iterators are designed to be called using a for item in iterator pattern, as shown. In other programming languages, this pattern is sometimes distinguished from a regular for loop by using a foreach keyword (C#) or special syntax like for x : somearr (Java).

Note that the itertools.combinations() iterator emits tuples, indicated by the parentheses in the output, rather than a list or a NumPy array.

It is possible but awkward to explicitly call the combinations iterator using the next() function like so:

comb_iter = it.combinations(xrange(n), k)

while True:

try:

c = comb_iter.next()

print "c = " + str(c)

except StopIteration:

break

print ""

By design, iterator objects don't have an explicit way to signal the end of iteration, such as a last() function or returning a special value like None. Instead, when an iterator object has no more items to emit and a call to next() is made, a StopIteration exception is thrown. To terminate a loop, you must catch the exception. Note that you could catch a general Exception rather than the more specific StopIteration.

Next, the demo program iterates through all combination elements for n = 5 and k = 3 using the successor() function of the program-defined Combination class:

print "Iterating through all elements using custom Combination class"

c = Combination(n, k)

while c is not None:

print "c = " + c.as_string()

c = c.successor()

print ""

The successor() function of the Combination class uses a traditional stopping technique by returning None when there are no more permutation elements. The logic in the program-defined successor() function is rather clever. Suppose n = 7, k = 4, and the current combination element is:

^ 0 1 5 6 ^

The next element in lexicographical order after 0256, using the digits 0 through 6, is 0345. The successor algorithm first finds the index i of the left-most item that must change. In this case, i = 1, which corresponds to item 2. The item at i is incremented, giving a preliminary result of 0356. Then the items to the right of the new value at i (56 in this case) are updated so that they are all consecutive relative to the value at i (45 in this case), giving the final result of 0345.

Notice that it's quite easy for successor() to determine the last combination element because it's the only one that has a value of n-k at index 0. For example, with n = 5 and k = 3, n-k = 2 and the last combination element is (2 3 4). Or, if n = 20 and k = 8, the last combination element would be (12 13 14 . . . 19).

One potential advantage of using a program-defined Combination class rather than the itertools.combinations() iterator is that you can easily define a predecessor() function. For example, consider the functions in Code Listing 20:

Code Listing 20: A Combination Predecessor Function

def predecessor(self): if self.data[self.n - self.k] == self.n - self.k: return None res = Combination(self.n, self.k) res.data = np.copy(self.data) i = self.k - 1 while i > 0 and res.data[i] == res.data[i-1] + 1: i -= 1 res.data[i] -= 1; i += 1 while i < k: res.data[i] = self.n - self.k + i i += 1 return res

def last(self): res = Combination(self.n, self.k) nk = self.n - self.k for i in xrange(self.k): res.data[i] = nk + i return res |

Then the following statements would iterate through all combination elements in reverse order:

c = Combination(n, k) # 0 1 2

c = c.last() # 2 3 4

while c is not None:

print "c = " + c.as_string()

c = c.predecessor()

Resources

For details about the Python itertools module, which contains the combinations iterator, see

https://docs.python.org/2/library/itertools.html.

The itertools.combinations iterator uses the Python yield mechanism. See

https://docs.python.org/2/reference/simple_stmts.html#yield.

4.6 Combination Element

When working with mathematical combinations, it's often useful to be able to generate a specific element. For example, if n = 5, k = 3, and the items are the integers (0, 1, 2, 3, 4), then there are 10 combination elements. When listed in lexicographical order, the elements are:

[0] (0, 1, 2)

[1] (0, 1, 3)

[2] (0, 1, 4)

[3] (0, 2, 3)

[4] (0, 2, 4)

[5] (0, 3, 4)

[6] (1, 2, 3)

[7] (1, 2, 4)

[8] (1, 3, 4)

[9] (2, 3, 4)

In many situations, you want to iterate through all possible combination elements, but in some cases you may want to generate just a specific combination element. For example, a function call like ce = comb_element(5) would store (0, 3, 4) into ce.

Using the built-in itertools.combinations iterator, the only way you can get a specific combination element is to iterate from the first element until you reach the desired element. This approach is impractical in all but the simplest scenarios. An efficient alternative is to define a custom Combination class and element() function that use NumPy arrays for data.

Code Listing 21: Generating a Combination Element Directly

# comb_elem.py # Python 2.7 import numpy as np # to make custom Combination class import itertools as it # has combinations iterator import scipy.special as ss # has comb() aka choose() function import time # to time performance class Combination: def __init__(self, n, k): self.n = n self.k = k self.data = np.arange(k) def as_string(self): s = "^ " for i in xrange(self.k): s = s + str(self.data[i]) + " " s = s + "^" return s @staticmethod def my_choose(n,k): if n < k: return 0 if n == k: return 1;

delta = k imax = n - k if k < n-k: delta = n-k imax = k ans = delta + 1 for i in xrange(2, imax+1): ans = (ans * (delta + i)) / i return ans def element(self, idx): maxM = Combination.my_choose(self.n, self.k) - 1 ans = np.zeros(self.k, dtype=np.int64) a = self.n b = self.k x = maxM - idx for i in xrange(self.k): ans[i] = self.my_largestV(a, b, x) x = x - Combination.my_choose(ans[i], b) a = ans[i] b -= 1 for i in xrange(self.k): ans[i] = (self.n - 1) - ans[i] result = Combination(self.n, self.k) for i in xrange(self.k): result.data[i] = ans[i] return result def my_largestV(self, a, b, x): v = a - 1 while Combination.my_choose(v, b) > x: v -= 1 return v # ===== def comb_element(n, k, idx): comb_it = it.combinations(xrange(n), k) i = 0 for c in comb_it: if i == idx: return c break i += 1 return None # ===== print "\nBegin combination element demo \n" n = 100 k = 8 print "Setting n = " + str(n) + " k = " + str(k) ces = ss.comb(n, k) print "There are " + str(ces) + " different combinations \n" idx = 100000000 print "Element " + str(idx) + " using itertools.combinations() is " start_time = time.clock() ce = comb_element(n, k, idx) end_time = time.clock() elapsed_time = end_time - start_time print ce print "Elapsed time = " + str(elapsed_time) + " seconds " print "" c = Combination(n, k) start_time = time.clock() ce = c.element(idx) end_time = time.clock() elapsed_time = end_time - start_time print "Element " + str(idx) + " using custom Combination class is " print ce.as_string() print "Elapsed time = " + str(elapsed_time) + " seconds " print "" print "\nEnd demo \n" |

C:\SciPy\Ch4> python comb_elem.py Setting n = 100 k = 8 There are 186087894300.0 different combinations Element 100000000 using itertools.combinations() is (0, 1, 3, 19, 20, 44, 47, 90) Elapsed time = 10.664860732 seconds Element 100000000 using custom Combination class is ^ 0 1 3 19 20 44 47 90 ^ Elapsed time = 0.001009821625 seconds End demo |

The demo program sets up a combinatorial problem with n = 100 items taken k = 8 at a time. So the first combination element is (0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7). The number of different combination elements is calculated using the comb() function from the scipy.special module and is 186,087,894,300. Note that in virtually all other programming language libraries, the function to calculate the number of different combination elements is called choose().

The demo calculates combination element 100,000,000 using a stand-alone, program-defined function comb_element() that uses the built-in itertools.combinations iterator. This approach took just over 10 seconds on a more or less standard desktop PC machine.

The demo calculates the same combination element using a program-defined Combination class and element() function. This approach took just over 0.001 seconds. The point is that Python iterators are designed to iterate well, but are not well suited for other scenarios.

The program-defined function comb_element() is:

def comb_element(n, k, idx):

comb_it = it.combinations(xrange(n), k) # make an iterator

i = 0 # index counter

for c in comb_it: # request next combination element

if i == idx: # are we there yet?

return c; break # if so, return current element and exit loop

i += 1 # otherwise bump counter

return None # should never get here

The function doesn't check if parameter idx is valid. You could do so using a statement like:

if idx >= ss.comb(n, k): # error

The obvious problem with using an iterator is that there's no way to avoid walking through every combination element until you reach the desired element. On the other hand, the program-defined element() function in the Combination class uses a clever mathematical idea called the combinadic to generate a combination element directly.

The regular decimal representation of numbers is based on powers of 10. For example, 7203 is (7 * 10^3) + (2 * 10^2) + (0 * 10^1) + (3 * 10^0). The combinadic of a number is an alternate representation based on the mathematical choose(n,k) function. For example, if n = 7 and k = 4, the number 27 is 6521 in combinadic form because 27 = choose(6,4) + choose(5,3) + choose(2,2) + choose(1,1). Using some rather remarkable mathematics, it's possible to use the combinadic of a combination element index to compute the element directly.

Resources

For details about the Python itertools module that contains the combinations iterator, see

https://docs.python.org/2/library/itertools.html.

For information about mathematial combinadics, see

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Combinatorial_number_system.

- 1800+ high-performance UI components.

- Includes popular controls such as Grid, Chart, Scheduler, and more.

- 24x5 unlimited support by developers.