CHAPTER 6

Charts for Associations

I mentioned in the Preface to this book my belief that graphics should always come before statistical analyses. The graphics can provide vital context and insight to the analyses that could be easily lost if the statistical procedures came first. Accordingly, in the chapters on univariate analyses, we first discussed charts for one variable (see Chapter 2) and then statistics for one variable (see Chapter 3). We continue that pattern for bivariate associations, with charts for association here in Chapter 6, and statistics for association in Chapter 7.

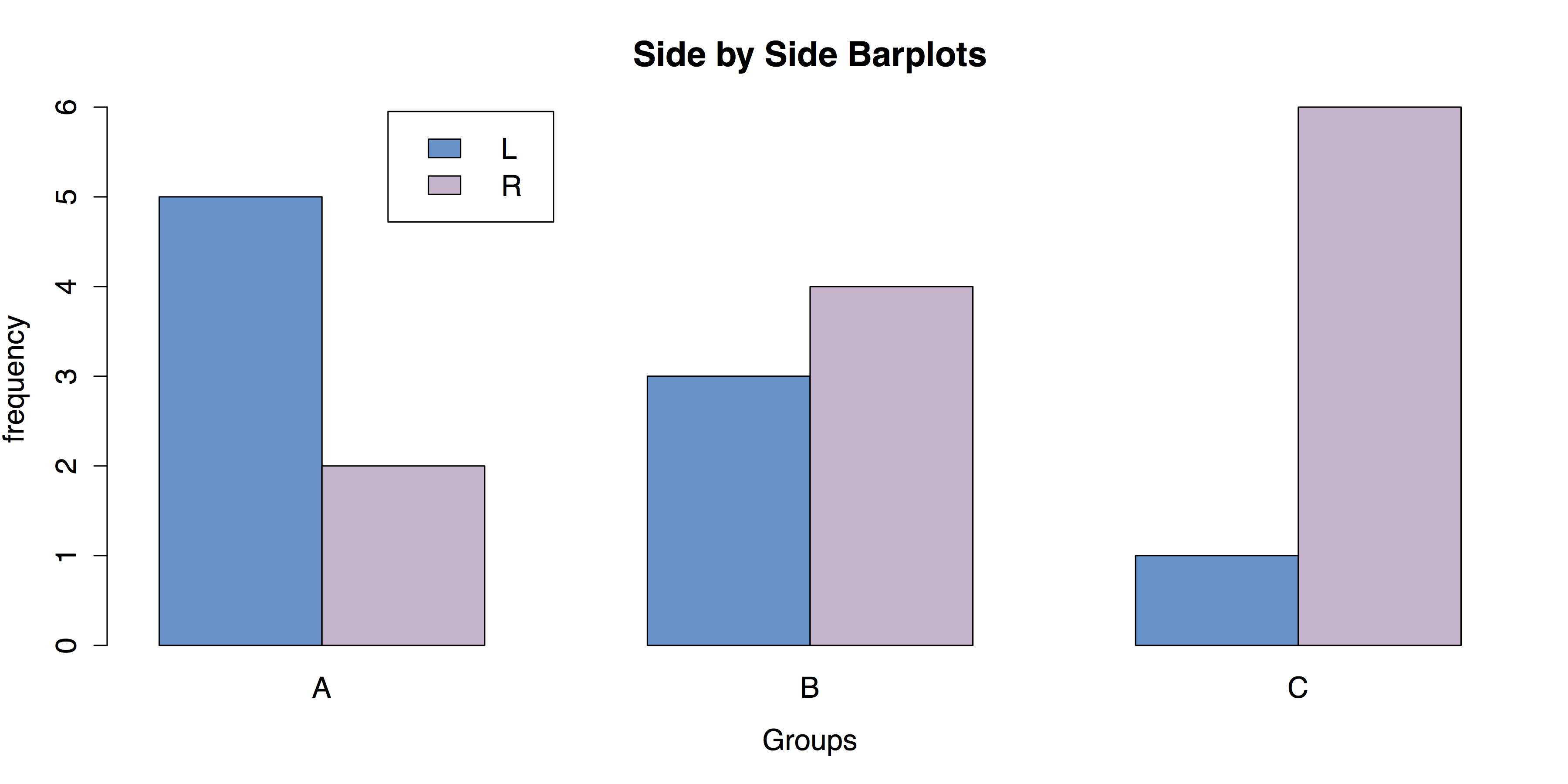

Grouped bar charts of frequencies

When a data set consists of joint categorizations based on two variables, grouped bar charts of the joint frequencies are often the most informative graph. In this section, we begin by entering a small 2 x 3 table of data directly into R. This is done by nesting the read.table() function within the as.matrix() function. We have to convert the data to a matrix since the plotting functions that we will use expect the data to be in vectors or matrices. In addition, two attributes are specified: header = TRUE, which indicates that the first row of data contains the names for the levels on the first categorical variable, and row.names = 1, which indicates that the first column contains the names for the levels on the second categorical variables. The data themselves consist of the frequencies for each combination of levels.

Sample: sample_6_1.R

# ENTER DATA data1 <- as.matrix(read.table( # Save as matrix header = TRUE, # First row is the header. row.names = 1, # First column is row names. # No comments within the data. text = ' X A B C L 5 3 1 R 2 4 6 ')) data1 # Check the data. |

The next step is to create the barplot using R’s barplot() function. The most important part of this command is the attribute beside = TRUE, which places the bars side-by-side instead of stacked.

# CREATE BARPLOT barplot(data1, # Use a new summary table. beside = TRUE, # Bars side-by-side vs. stacked. col = c("steelblue3", "thistle3"), # Colors main = "Side by Side Barplots", xlab = "Groups", ylab = "frequency") |

It is possible to add a legend as an attribute in the barplot() command. However, an interesting alternative is to add the legend interactively. By first making the plot with the previous code and then executing the following code, the cursor changes to crosshairs and allows you to manually position the legend within the plot:

# ADD LEGEND INTERACTIVELY legend(locator(1), # Use mouse to locate the legend. rownames(data1), # Use matrix row names (A & B). fill = c("steelblue3", "thistle3")) # Colors |

The resulting grouped bar plot is shown in Figure 24.

- Grouped Bar Chart for Frequencies

As usual, once you have saved your work, you should clean the workspace by removing any variables or objects you created with rm(list = ls()).

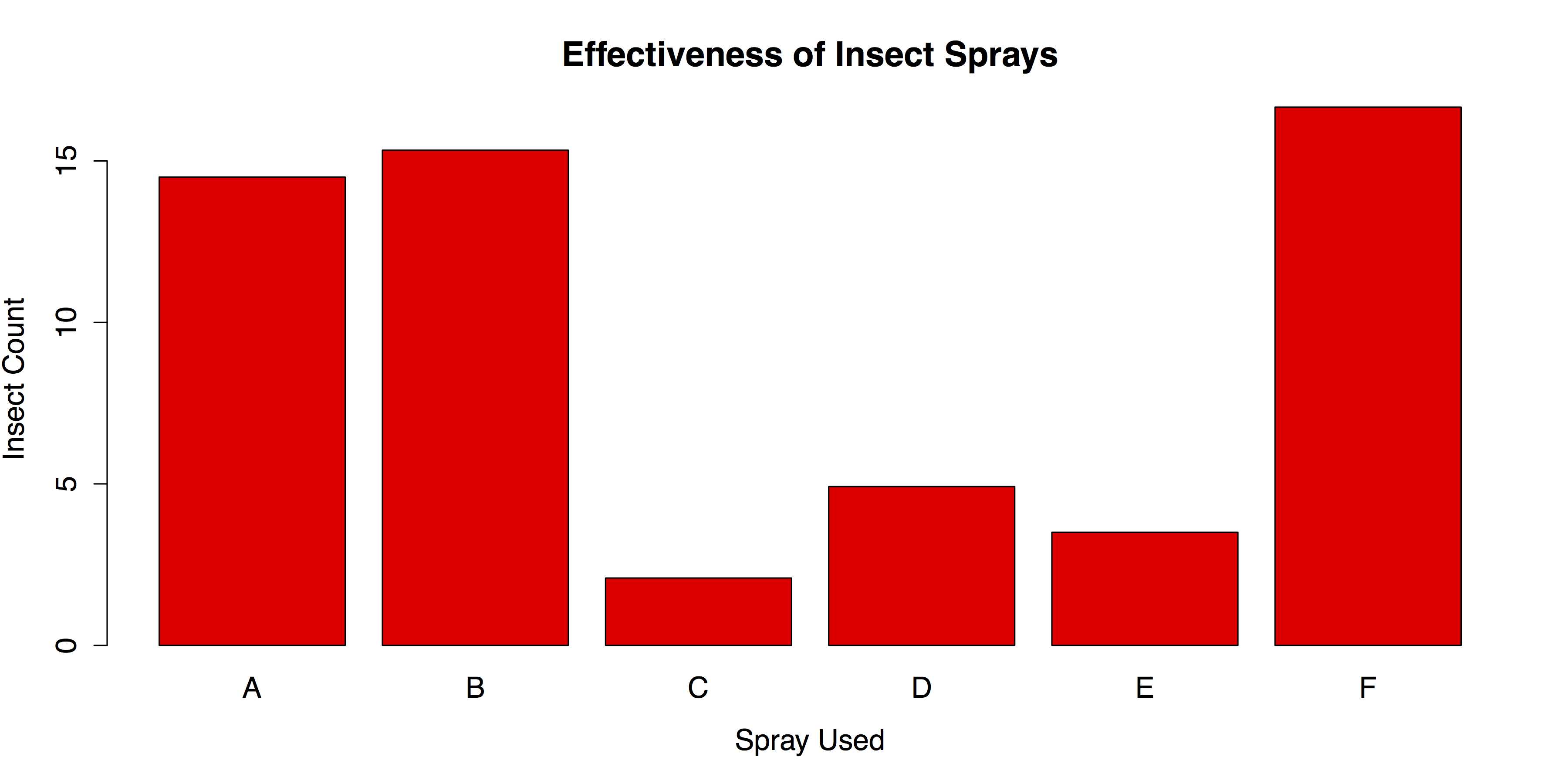

Bar charts of group means

When data consist of quantitative data for several groups on a single categorical variable, then a bar chart of group means can be helpful. To create this chart in R, it is necessary to reorganize the raw data into a table of means, which can then be charted with the same barplot() function that we used in the last section. In this example we will use the InsectSprays data from R’s datasets package.

Sample: sample_6_2.R

# LOAD DATA require("datasets") # Load the datasets package. spray <- InsectSprays # Load data with shorter name. |

In order to make a bar chart of means, we first need to save the means into their own object. We can do this with the aggregate() function, in which the outcome variable spray$count is a function of spray$spray and FUN = mean requests the means.

# GET GROUP MEANS means <- aggregate(spray$count ~ spray$spray, FUN = mean) means # Check the data. |

The resulting data frame means consists of a column of index values and a column of means. We need to remove the column of names and transpose the means. We can do this with the transpose function t() and the argument [-1], which excludes the first column. We then put the group names back in as column names with the colnames() function and specifying mean[, 1], which calls for all rows of the first column. The transposed data and columns names are saved into a new object, mean.data.

# REORGANIZE DATA FOR BARPLOT mean.data <- t(means[-1]) # Removes the first column, transposes the second. colnames(mean.data) <- means[, 1] # Add group names as column names. mean.data |

Once the data have been rearranged in this manner, all that remains is to call the barplot() function.

# BARPLOT WITH DEFAULTS barplot(mean.data) |

It is, however, useful to add some options to barplot(), especially to add titles and labels.

# BARPLOT WITH OPTIONS barplot(mean.data, col = "red", main = "Effectiveness of Insect Sprays", xlab = "Spray Used", ylab = "Insect Count") |

This will produce the chart shown in Figure 25.

- Bar Chart of Group Means

Finish by cleaning the workspace and removing any variables or objects you created.

# CLEAN UP detach("package:datasets", unload = TRUE) # Unloads the datasets package. rm(list = ls()) # Remove all objects from workspace. |

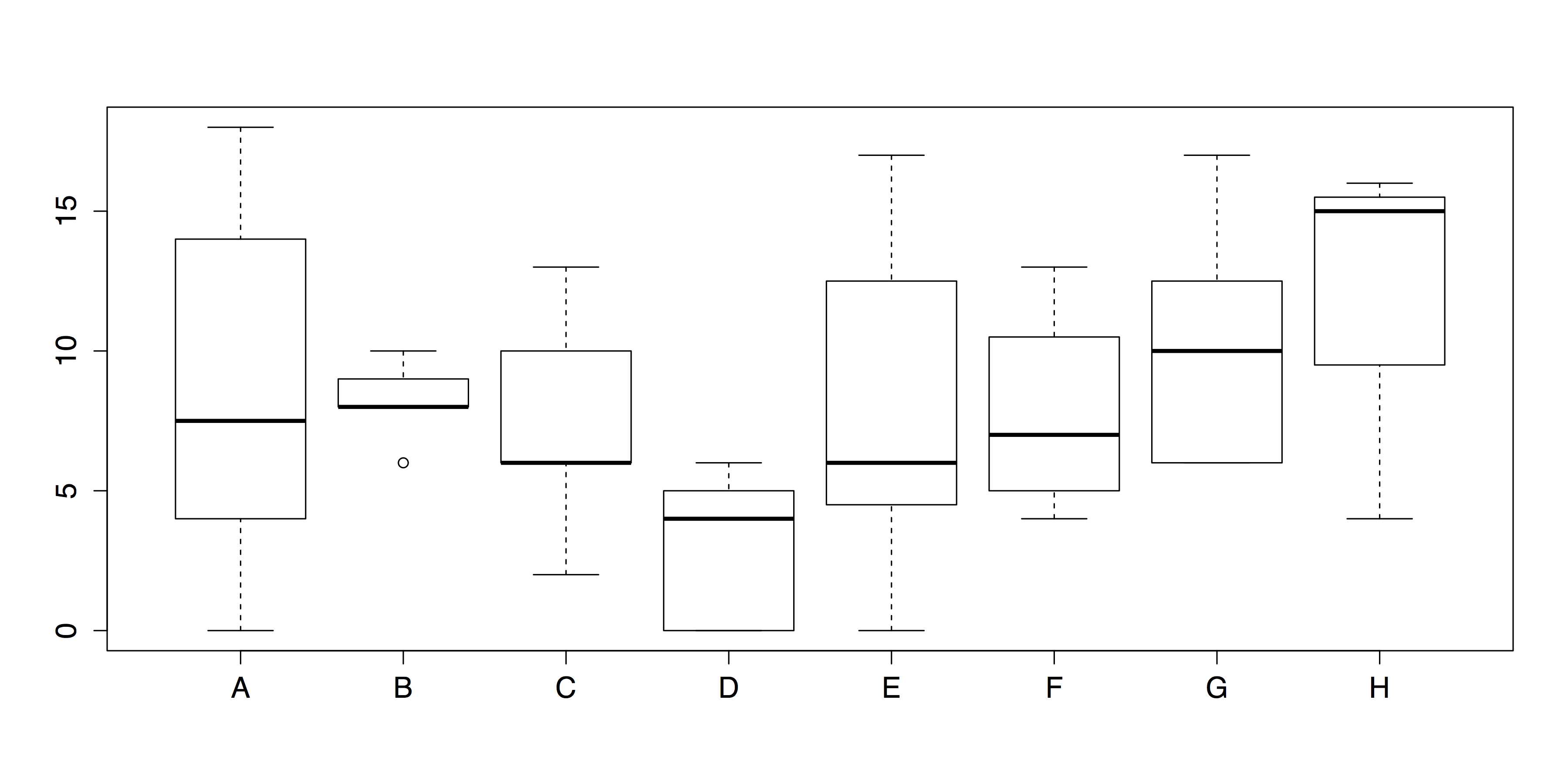

Grouped box plots

In the last section we looked at bar charts for group means. While such a chart can be useful, it only shows one piece of data, the mean, for each group. It may also be important to look at the entire distribution of scores for each group. This would allow you to check for outliers by group as well as get an intuitive feel for how well your data meet statistical assumptions like homogeneity of variance.

For this example, we will use the painters data set from the MASS package.[17] This data set contains 18th century art critic Roger de Piles’ judgments of 54 classical painters on four characteristics: composition, drawing, color, and expression.[18] The painters are classified according to their “school.” This is indicated by a factor level code as follows: "A": Renaissance; "B": Mannerist; "C": Seicento; "D": Venetian; "E": Lombard; "F": Sixteenth Century; "G": Seventeenth Century; "H": French. These classifications form the basis of our analysis.

Sample: sample_6_3.R

# LOAD DATA # Use data set "painters" from the package "MASS" require("MASS") data(painters) painters[1:3, ] Composition Drawing Colour Expression School Da Udine 10 8 16 3 A Da Vinci 15 16 4 14 A Del Piombo 8 13 16 7 A |

The data set is well formatted and ready for use with R’s boxplot() function. All that is necessary is to specify the outcome variable and categorizing variable. In this case, these are painters$Expression and painters$School, respectively.

# GROUPED BOXPLOTS WITH DEFAULTS # Draw boxplots of outcome (Expression) by group (School) boxplot(painters$Expression ~ painters$School) |

The default boxplot produced by this code is displayed in Figure 26.

- Grouped Boxplots (Default Chart)

As a chart, Figure 26 has one glaring omission: the groups do not have meaningful labels. Instead, they are categorized as A, B, C, and so on. This defeats the purpose of the chart. Consequently, it is important to add those labels using the names() attribute. It is also a good idea to add titles, axis labels, and other changes to make the chart both more informative and more attractive. Part of this change will involve using the RColorBrewer package to set colors for the boxplots.

# GROUPED BOXPLOTS WITH OPTIONS require("RColorBrewer") boxplot(painters$Expression ~ painters$School, col = brewer.pal(8, "Pastel2"), names = c("Renais.", "Mannerist", "Seicento", "Venetian", "Lombard", "16th C.", "17th C.", "French"), boxwex = 0.5, # Width of box as proportion of original. whisklty = 1, # Whisker line type; 1 = solid line staplelty = 0, # Staple (line at end) type; 0 = none. outpch = 16, # Symbols for outliers; 16 = filled circle. outcol = brewer.pal(8, "Pastel2"), # Color for outliers. main = "Expression Ratings of Painters by School from \"painters\" Data set in \"MASS\" Package", xlab = "Painter's School", ylab = "Expression Ratings") |

Note that there is no + or other line break in main for the title; R observes the break in the code as a typographic instruction. The improved boxplots are shown in Figure 27.

- Grouped Boxplots with Labels and Options

Once you have saved your work, you should clean the workspace by removing any variables or objects you created.

# CLEAN UP detach("package:MASS", unload = TRUE) # Unloads MASS package detach("package:RColorBrewer", unload = TRUE) # Unloads RColorBrewer package. rm(list = ls()) # Remove all objects from workspace. |

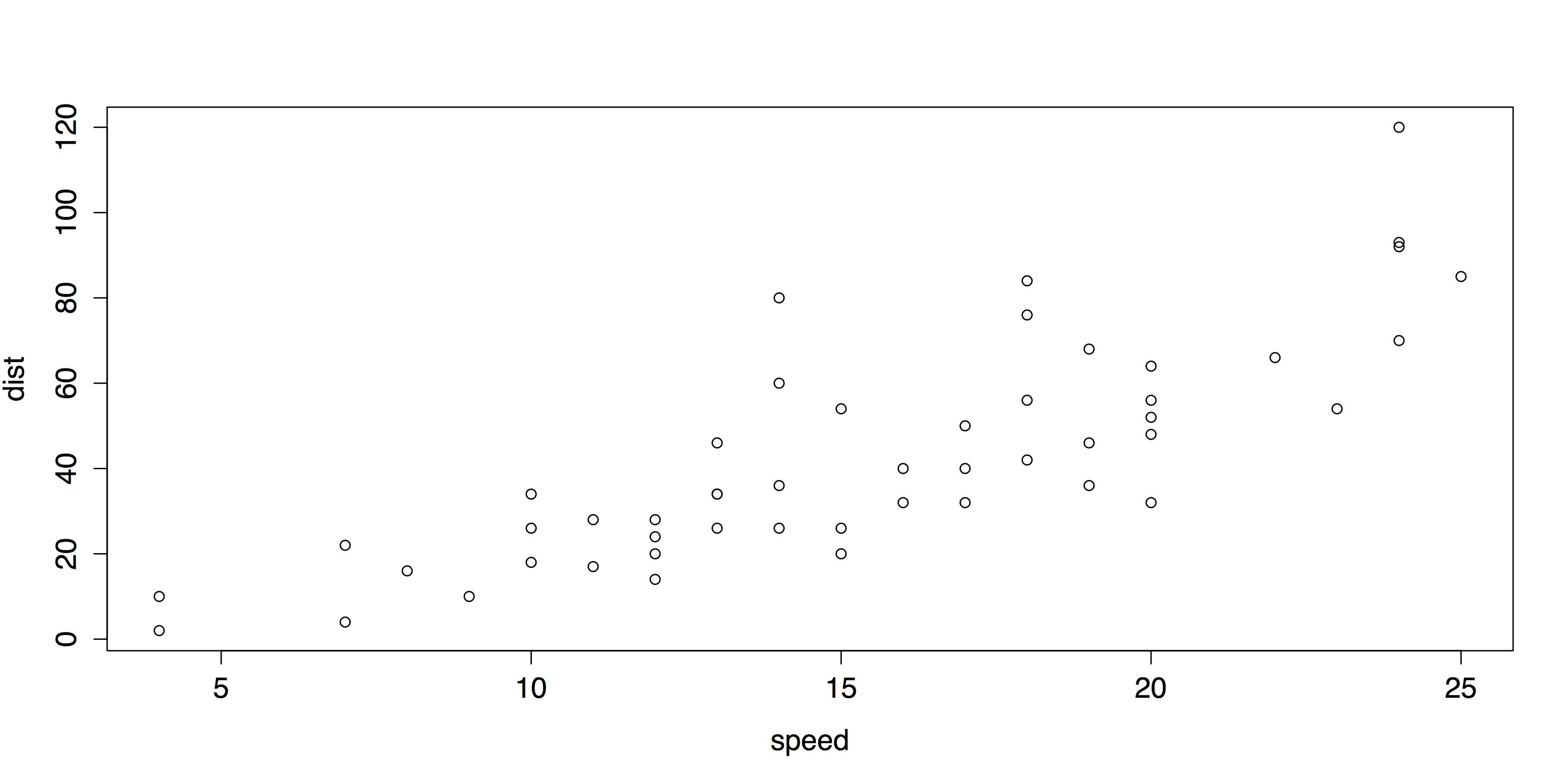

Scatter Plots

Perhaps the most common and most useful chart for visualizing the association between two variables is the scatter plot. Scatter plots are best used when the two variables are quantitative—that is, interval or ratio level of measurement—although they can be adapted to many other situations. In the base installation of R, the general-purpose plot() function is typically used for scatter plots. It works well both in its default configuration and with its many options. In addition, it is possible to overlay a variety of regression lines and smoothers.

For this example, we will use the cars data from R’s datasets package.

Sample: sample_6_4.R

# LOAD DATA require(“datasets”) # Load datasets package. data(cars) |

Because the cars data set contains only two variables—speed and dist (i.e., distance to stop from the corresponding speed)—and both are quantitative, it is possible to have nothing more than the name of the data set as an argument to the plot() function.

# SCATTER PLOT WITH DEFAULTS plot(cars) |

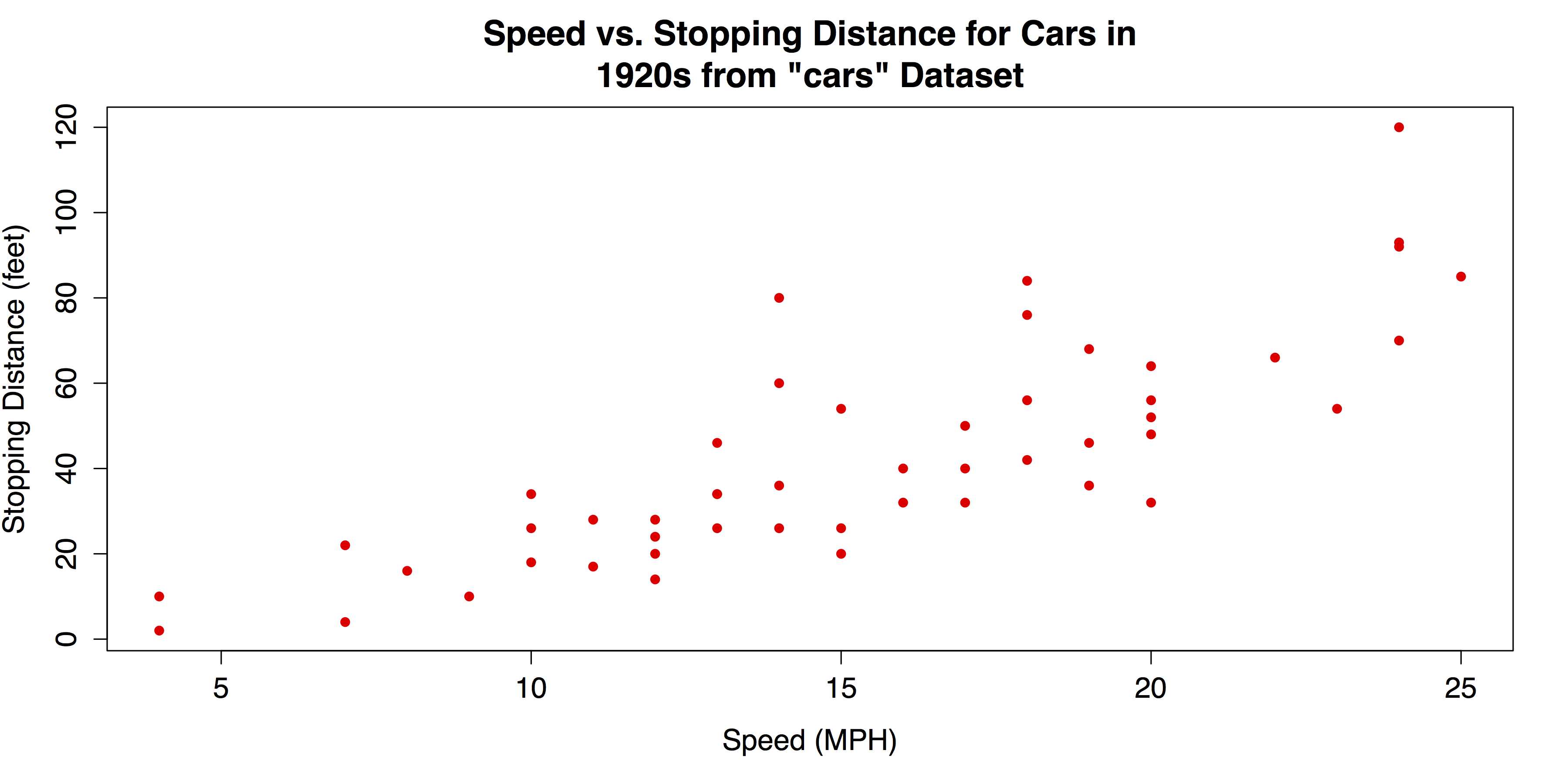

This produces the scatter plot shown in Figure 28.

- Default Scatter Plot with plot()

And while the chart in Figure 28 is adequate, plot() also provides several options for labels and design.

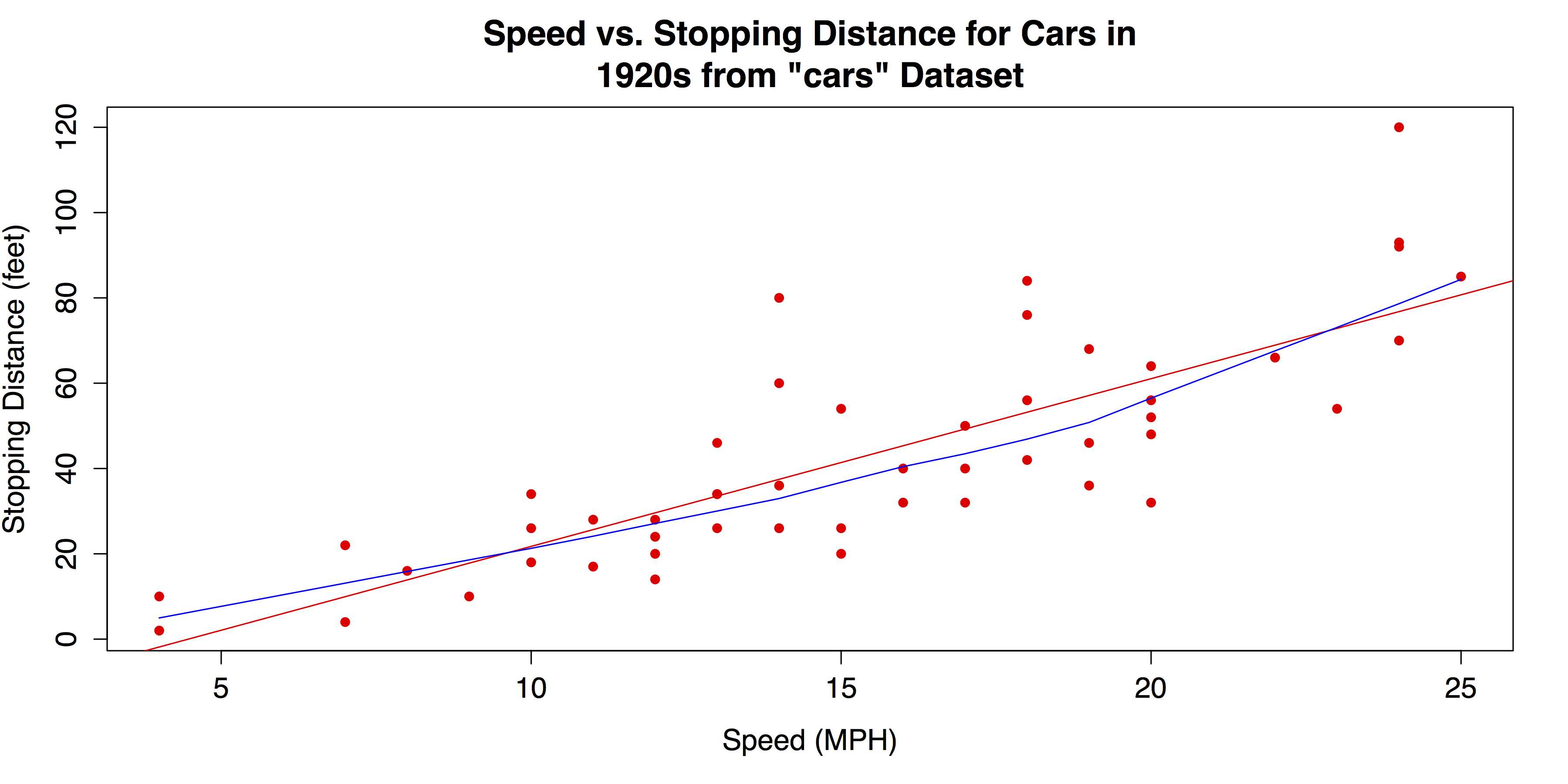

# SCATTER PLOT WITH OPTIONS plot(cars, pch = 16, col = "red", main = "Speed vs. Stopping Distance for Cars in 1920s from \"cars\" Data set", xlab = "Speed (MPH)", ylab = "Stopping Distance (feet)") |

The revised scatter plot is shown in Figure 29.

- Revised Scatter Plot with plot()

The upward pattern that indicates a positive association between the two variables in Figure 29 is easy to see. However, the relationship can be even clearer if fit lines are added. In the following code, a linear regression line will be overlaid with the abline() function, which takes a linear regression model from the lm() function as its argument. In addition, a lowess line—locally weighted scatter plot smoothing—can be added with the lines() function, which takes the lowess() function as its argument. See ?abline, ?lines, and ?lowess for more information on these functions.

# ADD REGRESSION & LOWESS # Linear regression line. abline(lm(cars$dist ~ cars$speed), col = "red") # "locally weighted scatterplot smoothing" lines(lowess(cars$speed, cars$dist), col = "blue") |

The scatter plot with the added fit lines is shown in Figure 30.

- Scatter Plot with Linear Regression and Lowess Fit Lines

For a final variation on the bivariate scatter plot, we can use the scatterplot() or sp() function from the coincidentally named car package (which, in this case, stands for "Companion to Applied Regression"). This package has many variations on scatter plots. The one we will use has marginal boxplots, smoothers, and quantile regression intervals. See help(package = "car") for more information.

First we must install and load the car package.

# INSTALL & LOAD "CAR" PACKAGE install.packages("car") # Download the package. require("car") # Load the package. |

Next, we can call the scatter plot function—which can be called with scatterplot() or sp()—with a few attribute arguments to alter the dots and provide titles and labels. Otherwise, the code is close to the default setup.

# "CAR" SCATTERPLOT sp(cars$dist ~ cars$speed, # Distance as a function of speed. pch = 16, # Points: solid circles. col = "red", # Red for graphic elements. main = "Speed vs. Stopping Distance for Cars in 1920s from \"cars\" Data set", xlab = "Speed (MPH)", ylab = "Stopping Distance (feet)") |

Figure 31 shows the resulting chart. The marginal boxplots, smoothers, and quantile regression intervals, all of which are included by default, make this a very information-dense graphic.

- Scatter Plot created with the car Package

Once you have saved your work, clean the workspace by removing any variables or objects you created.

# CLEAN UP detach("package:datasets", unload = TRUE) # Unloads datasets package. detach("package:car", unload = TRUE) # Unloads car package. rm(list = ls()) # Remove all objects from workspace. |

- 1800+ high-performance UI components.

- Includes popular controls such as Grid, Chart, Scheduler, and more.

- 24x5 unlimited support by developers.