CHAPTER 1

Introduction

I still remember the days when I got my hands on my first copy of Visual Studio. Back then, it was sold together with a pair of books, one of which was a straight printout of MSDN documentation. The technology of choice was, of course, C++ together with Microsoft Foundation Classes (MFC). Feature-wise, Visual Studio back then was nothing more than a combination of a text editor with some syntax highlighting and IntelliSense (Microsoft’s term for what we typically call code completion), together with an integrated compiler and debugger.

Back then, Visual Studio ran perfectly fine on a machine with 16MB (that’s megabytes) of RAM. While it is not my intention to walk down the memory lane of Visual Studio releases, I am currently using Visual Studio 2017 on a laptop with 16 gigabytes of RAM, precisely 1,000 times more than we had back in the days of Visual Studio 1997. Ironically, Visual Studio today feels a lot more sluggish than it did 20 years ago.

How has it come to this? I would argue that this happened due to lack of competition. True, Visual Studio did have competitors of sorts in the .NET space (SharpDevelop and MonoDevelop), but they were always enthusiast-grade and, as with many open-source projects, did not receive enough attention to become viable alternatives. It also didn’t help that, at the time, Microsoft was the ultimate gatekeeper of all things related to both .NET and the C# programming language, not to mention the support for various Microsoft-specific technologies. To an extent, this is still the case: if you want to work with Microsoft-centric tech stack (such as SharePoint, Dynamics or BizTalk), you would still most likely use Visual Studio.

JetBrains Rider, the subject of this book, is the first competitor to Visual Studio that has a chance to displace the hegemony. And as such, it’s worth paying attention to, because the amount of value it brings over what Visual Studio offers—both in terms of coding features as well as the overall platform—is, in my opinion, sufficient for it to become the primary .NET IDE in the near future.

What’s in this book

This book covers the core features of Rider, the .NET-centric IDE made by JetBrains. I focus on the IDE’s support for the C# language (I hope you will forgive me for omitting Visual Basic and F#—they are also supported, of course) as well as other languages (XAML, web languages, etc.) and technologies (such as WPF and ASP.NET). In actual fact, since Rider is itself a blend of two distinct technologies (the IntelliJ platform and ReSharper), we are going to discuss both the features offered by the platform (such as source control capabilities) as well as the core editing experiences supported by the editor (including code completion, navigation, and a wealth of other functionality).

Some historical perspective

To start with, let’s talk about JetBrains, a prominent producer of developer tools. JetBrains makes a lot of different products, but we need to talk about two key ones.

The first is called IntelliJ IDEA, and it is a Java (gasp!) integrated development environment (IDE). Yes, it’s a Java IDE, written in Java (the latest developments use Kotlin, a much more palatable language), but IDEA is built on a foundation called the IntelliJ Platform. It is on this platform that JetBrains builds all of its IDEs, supporting many of today’s programming languages. The IntelliJ platform is open source, so anyone who wants to build an IDE for a particular language can use it as a foundation to build upon. The IntelliJ platform is extensible and customizable—it has a great plug-in API, and there are many open-source plug-ins out on GitHub that one can learn from. Crucially, since the IntelliJ platform is JVM-based, it is, by definition, cross-platform.

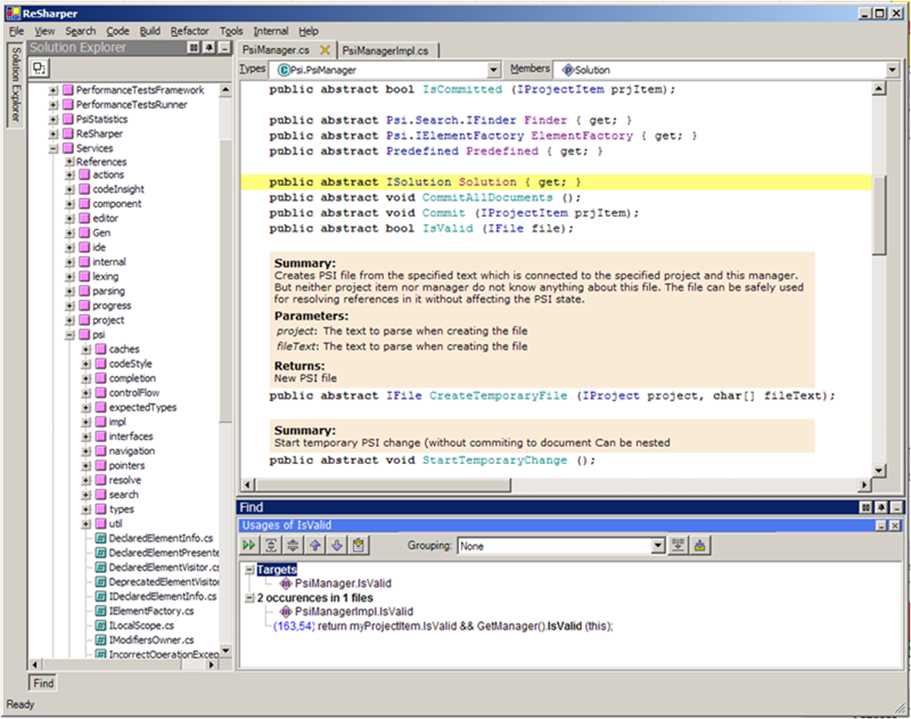

But we are not here to discuss the JVM, are we? We are here to talk about .NET and related technologies. And so, a long time ago, JetBrains did, in fact, consider building a standalone C# IDE. Here is proof—this screenshot was not easy to obtain!

Figure 1: Early Prototype of JetBrains .NET IDE

Eventually, they decided against it and made something called ReSharper instead. ReSharper is a Visual Studio plug-in that provides enhanced navigation, refactoring, code analysis, and many more features for Visual Studio users. Essentially, ReSharper included all those features that JetBrains intended to put in their standalone IDE.

And so, over a decade passed, with ReSharper becoming one of the most popular Visual Studio plug-ins on the market. It looked as though this setup would last forever, but then something interesting happened: Microsoft open-sourced Roslyn (the C# and VB.NET compilers) and started making .NET cross-platform. They also adapted the Electron (formerly Atom-shell) framework and began building a brand new, cross-platform IDE called Visual Studio Code. They also acquired Xamarin, a company with a product for making cross-platform mobile apps using C#, and created the .NET Standard, a specification that all .NET Framework implementations have to follow.

All of these events gave JetBrains the idea to finally make a standalone IDE. That IDE ended up being called Rider (an abbreviation, of sorts, for “ReSharper IDE”): a unique technological undertaking, merging the JVM-based platform and .NET-based functionality into a single product.

What is Rider?

So, what is Rider? Put simply, it is a standalone, .NET-centric IDE. When I say .NET-centric, I don’t just mean C# and VB, but also the different .NET platforms (such as .NET Core) as well as different .NET-based platforms and frameworks.

Rider uses the ReSharper infrastructure as a backend, and ReSharper supports not just the C# and VB.NET languages, but also the web languages such as JavaScript and TypeScript, and various markup languages. It also comes with technology-specific support for things like WPF and ASP.NET.

In addition, Rider is built on the mature and technologically accomplished IntelliJ platform, which means it gets lots of functionality “for free.” For example, it comes with support for many different version control systems. The IntelliJ platform serves as Rider’s frontend and has the potential to host other languages in addition to the ones supported by Rider’s default installation.

The biggest question of all is why should you even bother using Rider, considering the fact that we’ve got Visual Studio from Microsoft? Okay, let’s try to list all of Rider’s main benefits:

- Rider includes all the functionality of ReSharper. This means that all those code inspections, refactorings, navigation capabilities, and other useful features that have been fine-tuned over more than a decade are baked right into the IDE. If you’re just using Visual Studio, you would have to buy ReSharper to get equivalent functionality.

- Since Rider is built on the mature IntelliJ platform, it gains many benefits from it, such as Versopm Control System (VCS) support and a huge number of plug-ins that have already been written for IntelliJ by both JetBrains and the developer community.

- Since the IntelliJ platform is JVM-based, Rider is cross-platform, whereas Visual Studio is still restricted to Windows.

- Rider offers superior performance. Visual Studio has become something of a behemoth, both in terms of installation size as well as its working set in memory. Rider is a lot more compact and responsive. Rider is also free from the burdens of Roslyn (unless you really need it, in which case you can explicitly enable it), utilizing its own infrastructure for code analysis. This means that, unlike ReSharper, you don’t need to have Roslyn running if you don’t need it.

- Unlike Visual Studio, Rider is 64-bit. In fact, it’s 64-bit only. This results in additional benefits, since access to more RAM implies that the IDE can store more of its indexing and analysis data in RAM as opposed to having to swap it to disk. The Visual Studio process is stuck in 32-bit mode, and there’s no sign this will change anytime soon.

- Finally, and this is a critical distinction, the back end of Rider, which is the ReSharper part, is out-of-process. It communicates with the IDE front end using reactive message passing. It’s very fast, but the out-of-process part offers interesting possibilities, such as a possible relaxation of the requirement that both parts of the IDE reside in the same memory space.

Now, it’s not all roses here; Visual Studio does have a few advantages. Of course, some of them are a result of Rider being a relatively young product.

- Visual Studio is the de facto standard for Windows development. We could argue about whether or not Windows itself is the stronghold it once was, but at least in the Microsoft ecosystem, Windows and Visual Studio still go hand in hand.

- Visual Studio, being Microsoft’s brainchild, covers all Microsoft technologies that are currently being shipped, including very Enterprise-y tech such as SharePoint, BizTalk, SQL Server, abd Microsoft Dynamics. As a result, if you are developing for these technologies, you might be better served by using Visual Studio, at least until Rider catches up to them.

- Visual Studio also comes not just with code editors, but also with various GUI and visual designers. The quality of these designers varies a lot (especially for WPF and the web), but if you do need them, then you might want to stick to Visual Studio.

- Visual Studio is also tightly integrated with Team Foundation Server, Microsoft’s teamware development product. Rider does support TFS source control, but obviously, when it comes to issue tracking and other TFS features, Rider doesn’t provide any integration out of the box.

- Visual Studio has a free Community edition (not to mention the parallel cross-platform reality of Visual Studio Code), whereas Rider is a purely commercial product.

A list of pros and cons isn’t really enough to figure out if Rider is for you. The only way to know for sure is to download Rider and try it. Speaking of which…

Getting Rider

First, it has to be said that Rider, just like (paid editions of) Visual Studio, is a commercial product that costs real money. However, JetBrains is kind enough to offer a 30-day trial for every single one of its products, so you get one month to try and figure out whether the IDE you downloaded is worth the money. They also offer free products for educational needs for anyone working on an open-source project (subject to a few criteria), and to Microsoft MVPs.

There are two ways of getting Rider: the somewhat boring approach of downloading it from the product page, or the classy, sophisticated way. The “cool” way is to use yet another product, called JetBrains Toolbox. It’s effectively a package manager that lets you install, update, and uninstall all of JetBrains’ products. It’s super useful because of its simplicity: you can use it to install or uninstall apps, update all your apps in a single click, and choose whether you want to install Early Access Preview (or even nightly!) product builds.

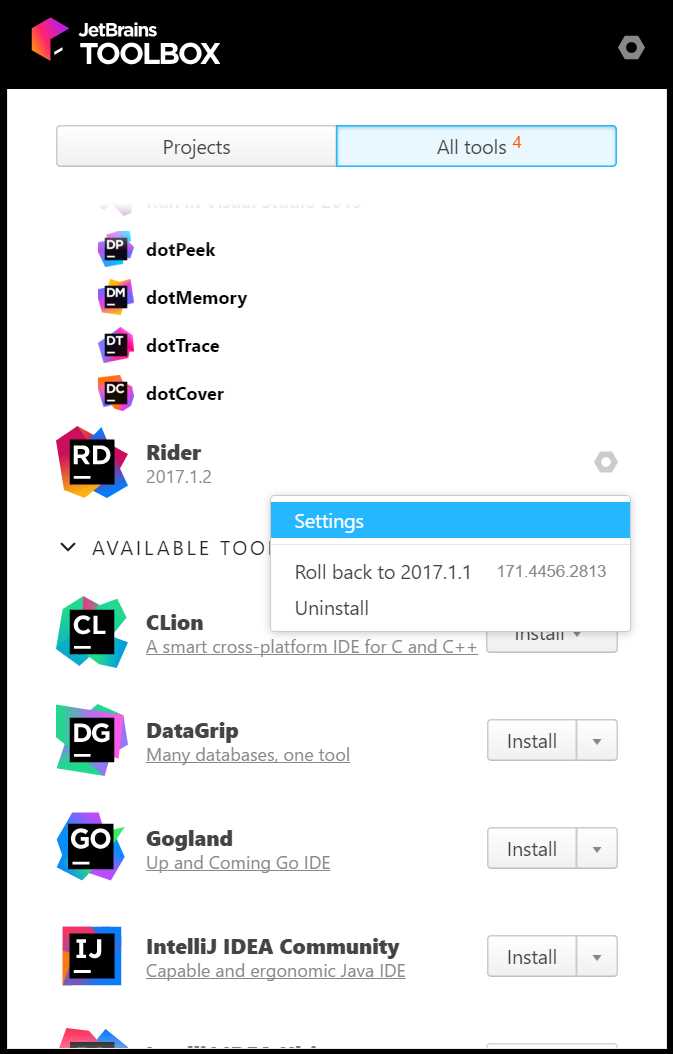

You can download the Toolbox from here. After you install it, you will get a pop-up window that looks like this:

Figure 2: JetBrains Toolbox

Now go ahead and find Rider, and click Install. After it has installed, click the Rider icon in the Toolbox, and Rider will fire up.

In most cases, you’ll never need to touch the Settings menu item shown in Figure 2, but there are cases when it’s necessary. Here are the options you can control using Rider’s settings:

- You can specify when you want to update Rider. The options are:

- Release: Only updates Rider to the production releases. This is suitable for most users because production releases are stable and will not offer any surprises.

- Release and EAP: Also updates Rider to the Early Access Preview versions, which are released by JetBrains prior to a new release to give users a taste of the features as they are coming out. This is a lot less stable, but EAP versions can include fixes you are waiting for before they go into a release version.

- Release, EAP and Nightly: For those who like living on the edge. Includes nightly builds, which implies even more risk in terms of the IDE not working, but you get to see the progress day-by-day.

- You can explicitly disable updates and tell Rider to stay on a specific version.

- You can enable automatic updates, because by default, the update process is manual (you need to open the Toolbox and press a button for an update to begin).

- You can specify the maximum heap size, the maximum amount of memory that Rider will be using (this is, effectively, the -Xmx setting on the JVM).

- You can edit the Java VM options. Keep in mind that Rider is composed of JVM and CLR parts, so you’ll only be editing settings for the Rider front end.

Tip: One practical use of editing the Java VM options is to enable the so-called Internal Mode. This is done using the -Didea.is.internal=true switch. This enables various diagnostic modes as well as certain utility actions. These are particularly useful for IDE debugging and plug-in developers.

That’s it! We’re ready to start exploring Rider.

- 1800+ high-performance UI components.

- Includes popular controls such as Grid, Chart, Scheduler, and more.

- 24x5 unlimited support by developers.