CHAPTER 2

Choosing the Topic and Creating the Flow

Say you have to deliver a presentation at a conference, during a meeting with customers or colleagues, or to a professor.

Where do you start? Usually, people will open their presentation tool and start creating slides, or they’ll go to some websites (internal to the company or external, like SlideShare) to find some decks and start assembling a presentation.

This technique leads to presentations that are full of details, but fail to deliver some value because they weren’t thought out in advance.

You have some slide decks that you can use

Let’s suppose that you have a slide deck (or more than one) that you could use to deliver your presentation. This is often the case with corporations. It can save you a lot of time, but people will immediately know if you aren’t feeling the slides as yours, if you don’t agree with the content, or if you could have used a different order or a different example.

If you’re in a hurry (because your boss told you the day before about the presentation) or if the slides are mandatory, you could use them without modifications. Try to visualize the flow in your mind and do a dry run to see if you can tell the right stories, or if you need some different examples (for example, to replace slides that don’t work well in your culture).

Slides are important, but you can still deliver a great session if you don’t have great slides. You could describe the value at the beginning of the presentation, even on the title slide, if you don’t have supporting slides at the beginning. In this way, you’ve set the playing field, and then you can follow the slides, using the right stories to deliver the value.

How to reorganize your slides

If you can create new slides, or rearrange existing slides, it’s your job to create the right flow.

Always start with the value, and try to remove all the details that aren’t important. Don’t immediately delete slides; you can hide them, or move them to the appendix. If slides are too complicated or too wordy, try to apply the techniques that you’ll see in Chapter 4 to simplify them.

Use the Slide Sorter with the right zoom to visualize the flow of the presentation.

Figure 1: Slide Sorter

In Figure 1, the core value of the presentation is about “making a great show.” To do it, everything starts with defining your standard. The presentation continues by stating that everybody could improve if they follow the right suggestions, like avoiding introducing yourself at the beginning instead of starting immediately with the value. (People should ask your name because they’re interested.) And so on.

You can exercise your ability to organize and rearrange slides by downloading existing presentations on a topic that you know, and trying to make your version of the deck. You can always improve a presentation, even a good one, by making it yours. Sometimes there are no modifications that you can make; in that case, you can still learn something from that presentation.

You can also exercise during meetings: try to visualize how you could have done the presentation that is being delivered.

You need or want to start from scratch

Before creating a new presentation from scratch, you should have delivered many presentations with slides created by somebody else that you’ve modified or rearranged. Studying the work of others and improving on it is a good way to exercise and nurture your creativity.[2]

When you’re ready to create your first presentation from scratch, my suggestion is to open a text editor and write the value of the presentation, which could be the only sentence that the audience should remember after your talk.

Then you can start to brainstorm ideas and stories, research facts around your core value, and write them down. Do you know your audience? Try to visualize them to help you understand their needs and why your value should be important for them. Try to brainstorm stories that will resonate with them.

Once you’ve done this activity, you can look at the items that you wrote and try to prioritize them and give them a logical order. At this point, you can start creating your slides. You don’t have to fit all the things that you’ve brainstormed; you should only add the most important one that allows you to deliver your stories to support the core value of your presentation.

The importance of stories and emotions

Stories (real or invented) are one of the most useful tools that you can use to improve your presentation. You can use a story to explain the value of your presentation. You can use a story to introduce your product or to create the need to understand more of it.

You can use stories in a technical presentation to explain why you’re using a specific technique, why you’re optimizing the performance of some code, or why it’s important to focus on usability.

Stories vs. facts

Facts don’t stick in our brain if we don’t already have a place for them. You can throw a lot of facts at your audience, but if people won’t remember them after some time, the effectiveness of your presentation was very low.

Emotions are a powerful way to recall facts that are stored in your memory. Stories are normally used to create or associate emotions with the facts that will follow.

As a geek, you might be tempted to use facts as your only weapon to impress your audience, creating slides and demos to show how good your work is, and how much you know a specific technology. That doesn’t stick.

Do you remember Bing Bong from the Disney/Pixar movie Inside Out?[3] At some point, he’s lost in the Memory Dump with all the disappearing memories. It’s an excellent image[4] to help you remember that facts will fade away without a good story.

Consider that many courses to improve your memory use strong emotions to connect facts and make them stick.

How to choose your stories

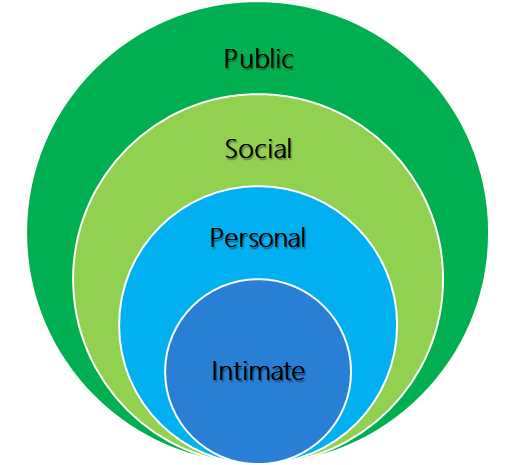

There’s a good book called Life Zones[5] that, among other things, explains that there are four zones in our lives.

Figure 2: Four life zones

The public zone is open to anyone. You’re in the public zone when you look around to find information and stimulation, when you’re completely anonymous, or when you’re together with a lot of people and interacting with them.

The social zone is where you perform an activity, like working or playing a sport, together with people that interact with you.

The personal zone is where you are sharing what you feel with people you trust. In the personal zone, you feel vulnerable because of this sharing.

The intimate zone is the innermost zone, where you’re more vulnerable because you’re with the people you care about most.

You can relate these zones to the kind of performance you’re delivering.

If you’re presenting facts to complete strangers without interaction and without questions from a powerful position (for example, as a professor behind a lectern), you could be in the public zone, where you’re not vulnerable (or just a little bit).

If you’re presenting to people you know, or you open yourself and interact with attendees, sharing information and generic stories, you’re in the social zone. This is the place where you’re more vulnerable, but where people start feeling a better connection.

If you’re presenting using personal stories, like how you used a product with your son, you’re in the personal zone where you’re more vulnerable, because it’s difficult to separate criticism from our personal experiences.

A presentation could contain a mix of those stories; you can start from the public zone and move to the social or the personal.

Be cautious: you could take a product remark as a personal criticism if you’re in the personal zone, and the audience (or part of it) is in the public or social zone. To become a better speaker, you need to handle this zone mismatch. Always ask for feedback from friends and other attendees about a remark that you felt was rude; perhaps other people didn’t feel the same.

Where do you find stories?

Stories are everywhere, all around us. Just pay attention to people, to strangers—on the way to work, at a park, anywhere.

A good story can be genuine, or you can modify it in some way to support your point. Just be sure to tell the truth if asked by some attendees.

Do you need help? The Storyteller’s Spellbook by James Whittaker[6] is a great book that helps you craft your stories.

How to create a story

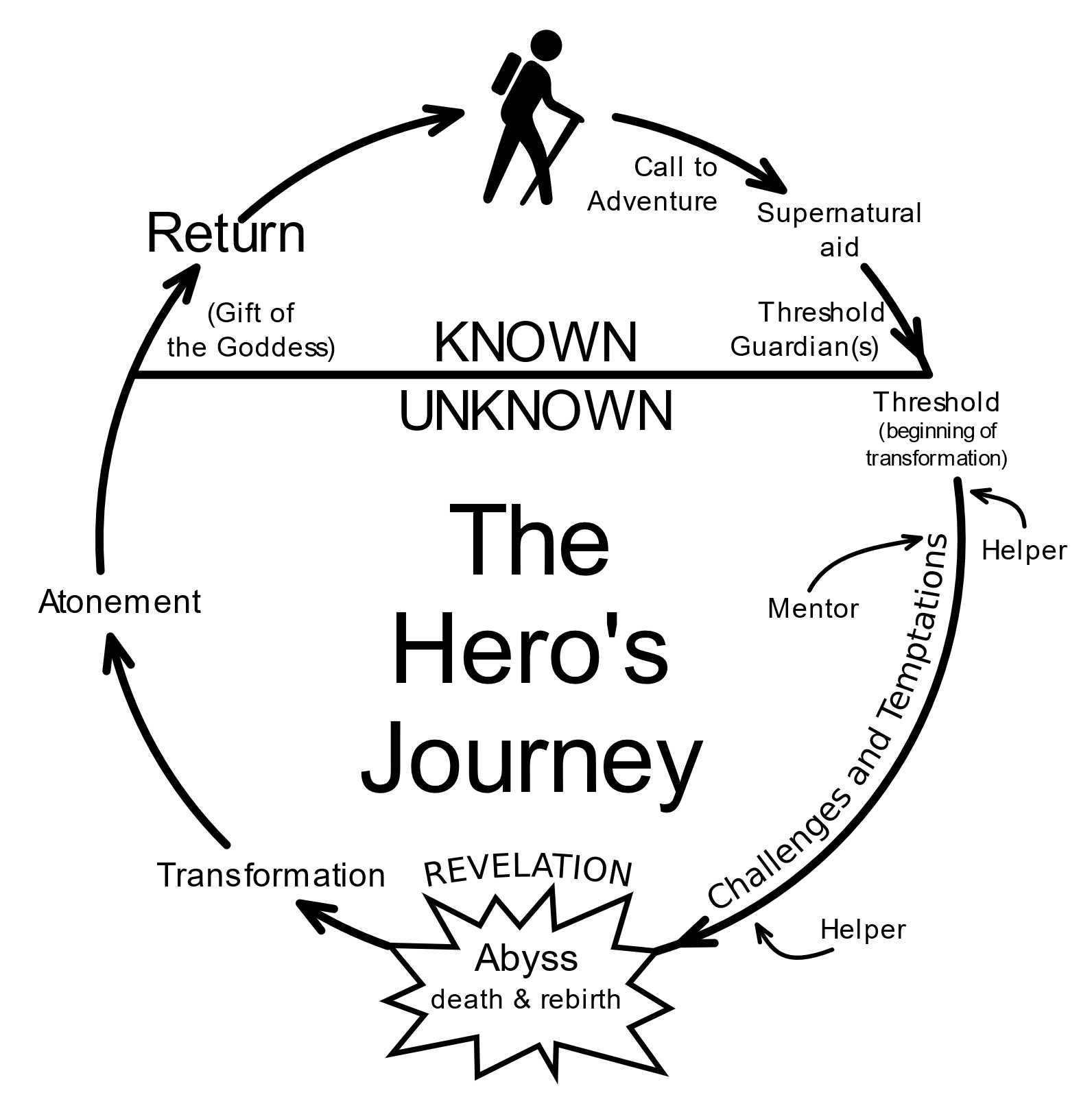

If you need a story but can’t find one, The Hero’s Journey[7] is a good template to create a new story. As you can see, many movies follow the path highlighted in the following figure.

Figure 3: The hero's journey. Source: Wikipedia.

The Harry Potter books, Star Wars, and The Lord of the Rings are just a few examples. Also, one particular Dilbert cartoon by Scott Adams was inspired by the hero’s journey some years ago .[8]

Influence without authority

Let’s explore a topic that is critical in most contexts. Sometimes, you need to present to people that are at your level or above you, and your presentation should influence them to take some action like sponsor your project, adopt your product, or change something in the company.

To prepare such a presentation, you can choose or create stories that are essential to let your message stick.

You need to understand why people resist change (for example, you’re proposing cloud to a company that still has all its servers on-premises), and when they’re receptive. You need to find the right emotions and motivations to understand different perspectives.

Another essential thing is understanding stakeholders’ challenges and motivations. Sometimes money isn’t the only drive; a good project could lead to being respected by other colleagues or managers.

You need to be receptive to their needs and discuss the benefits of the change. If they can be open with you, you can understand their point of view.

Adam Grant’s book Give and Take[9] has an entire chapter about using the right motivation to induce a change in people or organizations. Sometimes you need to question the status quo before presenting your solution, because it’s easier to remain static if you don’t feel the pain.

Start with value

Speakers who introduce themselves and their company, then move to the agenda slide, then start with a long trip around the topic that they want to explain usually do this because it’s the typical way to start a presentation—and when they’re anxious, they’ll go back to their comfort zone.

Being able to start directly with value requires some preparation. There are many possible ways to do it:

- Tell a story that shows the value. We’ve already covered why stories are important, so no need to explain this.

- Ask a question that allows you to uncover the value. Questions are a powerful tool if you can handle all the possible answers, and not just the answers that you expect.

- Go around the table. If there are fewer than ten to fifteen people, you can start by asking people to answer a simple question related to the value. You must keep control of the time, and you shouldn’t let an attendee steal your focus.

- Arouse curiosity. If you can use a prop during your presentation, it could help you arouse curiosity about the value. Bill Gates released mosquitos during a TED talk to raise awareness about malaria.[10]

Tip: Try to have more than one way to start your presentation. You need to master all of them and choose the one that better suits your mood or your audience. The first few minutes of a presentation are essential for getting people’s attention and keeping it for the rest of the session. Use this time in the best way possible!

- 1800+ high-performance UI components.

- Includes popular controls such as Grid, Chart, Scheduler, and more.

- 24x5 unlimited support by developers.