CHAPTER 3

Text Operators

As we saw in the previous chapter, PDFs use streams to define the appearance of a page. Content streams typically consist of a sequence of commands that tell the PDF viewer or editor what to draw on the page. For example, the command (Hello, World!) Tj writes the string “Hello, World!” to the page. In this chapter, we’ll discover exactly how this command works, and explore several other useful operators for formatting text.

The Basics

The general procedure for adding text to a page is as follows:

- Define the font state (Tf).

- Position the text cursor (Td).

- “Paint” the text onto the page (Tj).

Let’s start by examining a simplified version of our existing stream.

|

BT |

First, we create a text block with the BT operator. This is required before we can use any other text-related operators. The corresponding ET operator ends the current text block. Text blocks are isolated environments, so the selected font and position won’t be applied to subsequent text blocks.

The next line sets the font face to /F0, which is the Times Roman font we defined in the 3 0 obj, and sets the size to 36 points. Again, PDF operators use postfix notation—the command (Tf) comes last, and the arguments come first (/F0 and 36).

Now that the font is selected, we can draw some text onto the page with Tj. This operator takes one parameter: the string to display ((Hello, World!)). String literals in a PDF must be enclosed in parentheses. Nested parentheses do not need to be escaped, but single ones need to be preceded by a backslash. So, the following two lines are both valid string literals.

|

(Nested (parentheses) don’t need a backslash.) |

Of course, a backslash can also be used to escape itself (\\).

Positioning Text

If you use pdftk to generate a PDF with the content stream at the beginning of this chapter (without the Td operator), you’ll find that “Hello, World!” shows up at the bottom-left corner of the page.

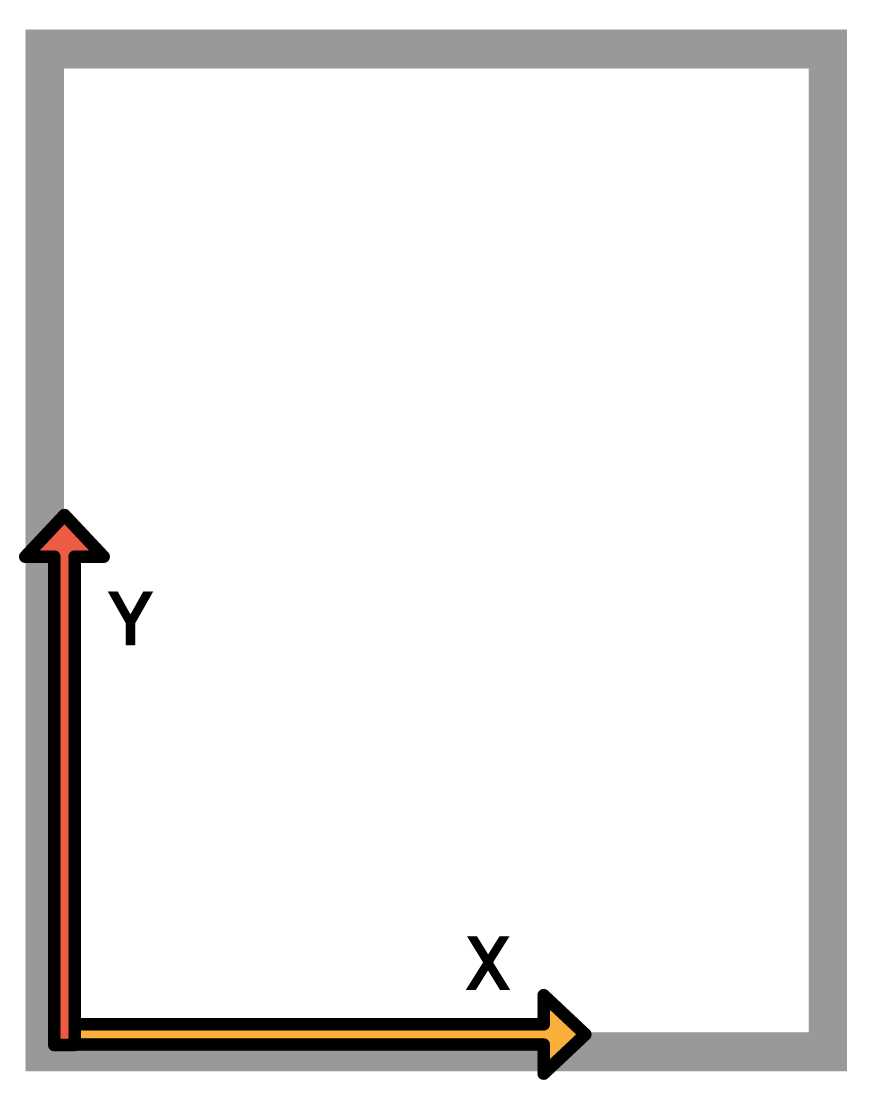

Since we didn’t set a position for the text, it was drawn at the origin, which is the bottom-left corner of the page. PDFs use a classic Cartesian coordinate system with x increasing from left to right and y increasing from bottom to top.

Figure 6: The PDF coordinate system

We have to manually determine where our text should go, then pass those coordinates to the Td operator before drawing it with Tj. For example, consider the following stream.

|

BT |

This positions our text at the top-left of the page with a 50-point margin. Note that the text block’s origin is its bottom-left corner, so the height of the font had to be subtracted from the y-position (792-50-36=706). The PDF file format only defines a method for representing a document. It does not include complex layout capabilities like line wrapping or line breaks—these things must be determined manually (or with the help of a third-party layout engine).

To summarize, pages of text are created by selecting the text state, positioning the text cursor, and then painting the text to the page. In the digital era, this process is about as close as you’ll come to hand-composing a page on a traditional printing press.

Next, we’ll take a closer look at the plethora of options for formatting text.

Text State Operators

The appearance of all text drawn with Tj is determined by the text state operators. Each of these operators defines a particular attribute that all subsequent calls to Tj will reflect. The following list shows the most common text state operators. Each operator’s arguments are shown in angled brackets.

- <font> <size> Tf: Set font face and size.

- <spacing> Tc: Set character spacing.

- <spacing> Tw: Set word spacing.

- <mode> Tr: Set rendering mode.

- <rise> Ts: Set text rise.

- <leading> TL: Set leading (line spacing).

The Tf Operator

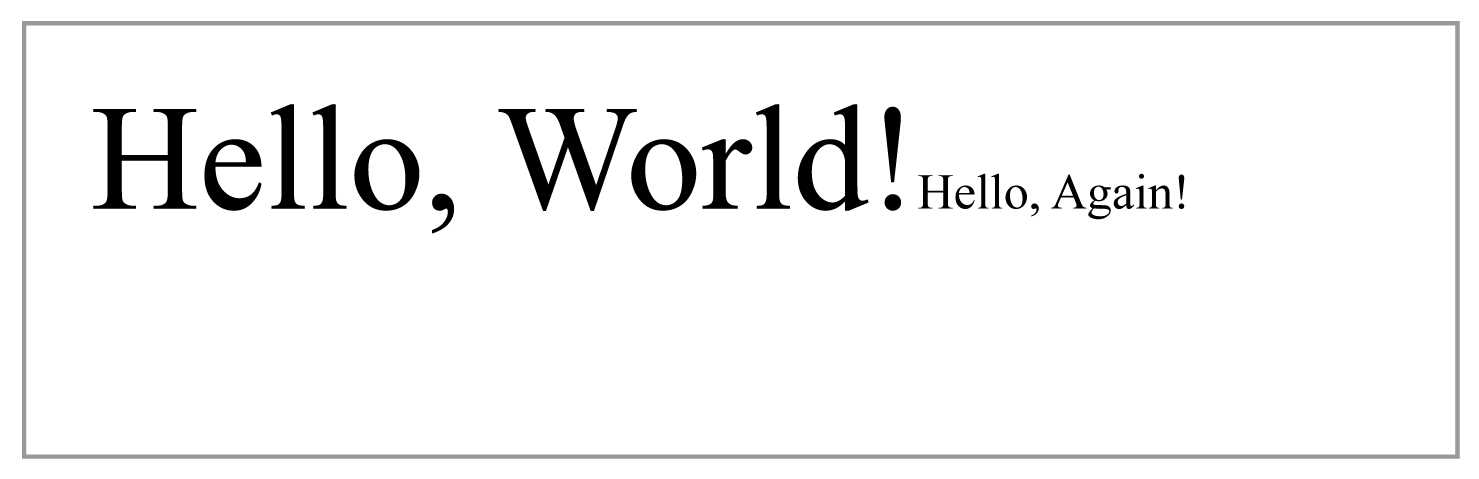

We’ve already seen the Tf operator in action, but let’s see what happens when we call it more than once:

BT |

This changes the font size to 12 points, but it’s still on the same line as the 36-point text:

Figure 7: Changing the font size with Tf

The Tj operator leaves the cursor at the end of whatever text it added—new lines must be explicitly defined with one of the positioning or painting operators. But before we start with positioning operators, let’s take a look at the rest of the text state operators.

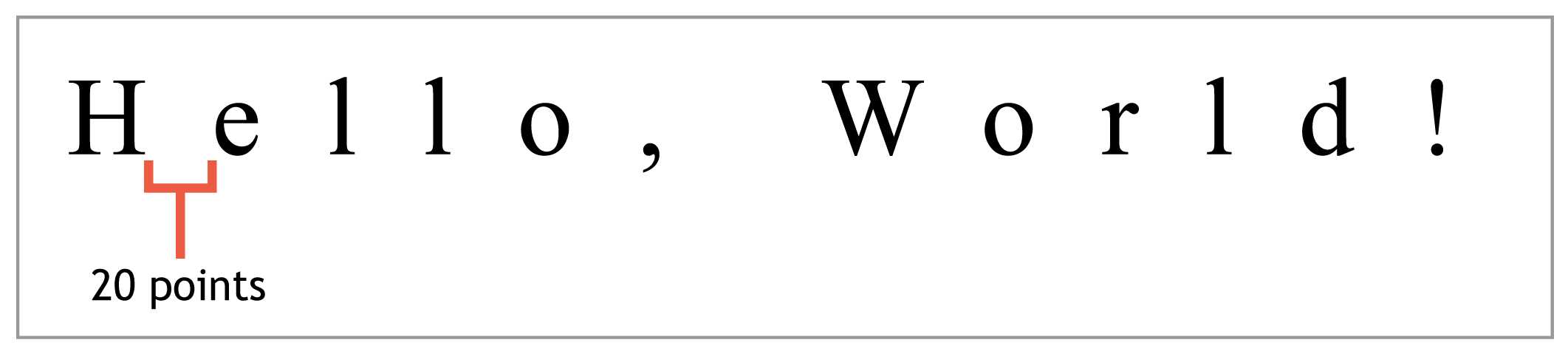

The Tc Operator

The Tc operator controls the amount of space between characters. The following stream will put 20 points of space between each character of “Hello, World!”

BT |

This is similar to the tracking functionality found in document-preparation software. It is also possible to specify a negative value to push characters closer together.

Figure 8: Setting the character spacing to 20 points with Tc

The Tw Operator

Related to the Tc operator is Tw. This operator controls the amount of space between words. It behaves exactly like Tc, but it only affects the space character. For example, the following command will place words an extra 10 points apart (on top of the character spacing set by Tc).

10 Tw |

Together, the Tw and Tc commands can create justified lines by subtly altering the space in and around words. Again, PDFs only provide a way to represent this—you must use a dedicated layout engine to figure out how words and characters should be spaced (and hyphenated) to fit the allotted dimensions.

That is to say, there is no “justify” command in the PDF file format, nor are there “align left” or “align right” commands. Fortunately, the iTextSharp library discussed in the final chapter of this book does include this high-level functionality.

The Tr Operator

The Tr operator defines the “rendering mode” of future calls to painting operators. The rendering mode determines if glyphs are filled, stroked, or both. These modes are specified as an integer between 0 and 2.

Figure 9: Text rendering modes

For example, the command 2 Tr tells a PDF reader to outline any new text in the current stroke color and fill it with the current fill color. Colors are determined by the graphics operators, which are described in the next chapter.

The Ts Operator

The Ts command offsets the vertical position of the text to create superscripts or subscripts. For example, the following stream draws “x²”.

BT |

Text rise is always measured relative to the baseline, so it isn’t considered a text positioning operator in its own right.

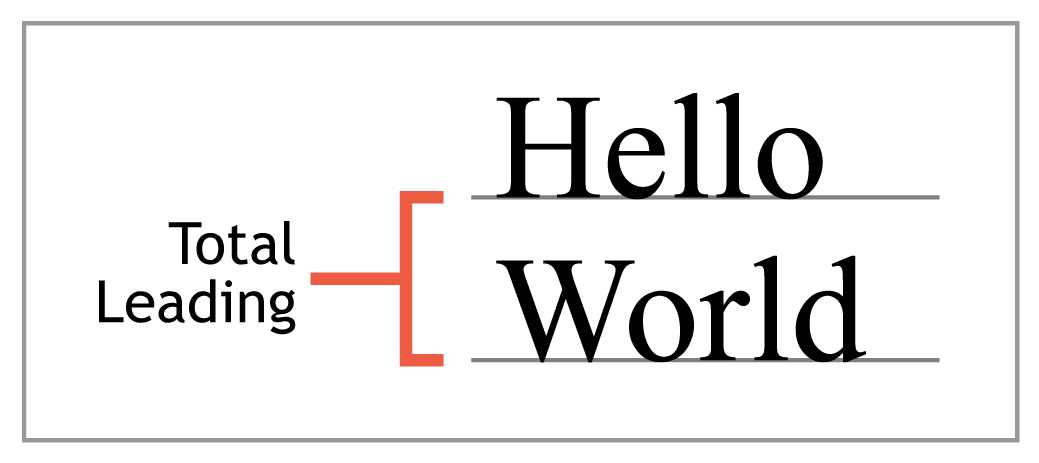

The TL Operator

The TL operator sets the leading to use between lines. Leading is defined as the distance from baseline to baseline of two lines of text. This takes into account the ascenders and descenders of the font face. So, instead of defining the amount of space you want between lines, you need to add it to the height of the current font to determine the total value for TL.

Figure 10: Measuring leading from baseline to baseline

For example, setting the leading to 16 points after selecting a 12-point font will put 4 points of white space between each line. However, font designers can define the height of a font independently of its glyphs, so the actual space between each line might be slightly more or less than what you pass to TL.

|

BT |

T* moves to the next line so we can see the effect of our leading. This positioning operator is described in the next section.

Text Positioning Operators

Positioning operators determine where new text will be inserted. Remember, PDFs are a rather low-level method for representing documents. It’s not possible to define the width of a paragraph and have the PDF document fill it in until it runs out of text. As we saw earlier, PDFs can’t even line-wrap on their own. These kinds of advanced layout features must be determined with a third-party layout engine, and then represented by manually moving the text position and painting text as necessary.

The most important positioning operators are:

- <x> <y> Td: Move to the start of the next line, offset by (<x>, <y>).

- T*: Move to the start of the next line, offset by the current leading.

- <a> <b> <c> <d> <e> <f> Tm: Manually define the text matrix.

The Td Operator

Td is the basic positioning operator. It moves the text position by a horizontal and vertical offset measured from the beginning of the current line. We’ve been using Td to put the cursor at the top of the page (50 706 Td), but it can also be used to jump down to the next line.

|

BT |

The previous stream draws the text “Hello, World!” then moves down 16 points with Td and draws “Hello, Again!” Since the height of the second line is 12 points, the result is a 4-point gap between the lines. This is the manual way to define the leading of each line.

Note that positive y values move up, so a negative value must be used to move to the next line.

The T* Operator

T* is a shortcut operator that moves to the next line using the current leading. It is the equivalent of 0 -<leading> Td.

The Tm Operator

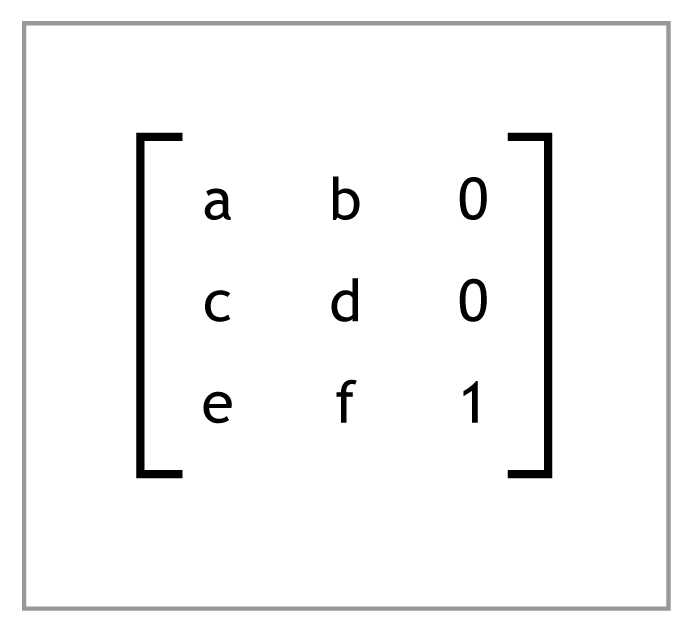

Internally, PDFs use a transformation matrix to represent the location and scale of all text drawn onto the page. The following diagram shows the structure of the matrix:

Figure 11: The text transformation matrix

The e and f values determine the horizontal and vertical position of the text, and the a and d values determine its horizontal and vertical scale, respectively. Altering more than just those entries creates more complex transformations like skews and rotations.

This matrix can be defined by passing each value as an argument to the Tm operator.

<a> <b> <c> <d> <e> <f> Tm

Most of the other text positioning and text state commands are simply predefined operations on the transformation matrix. For example, setting Td adds to the existing e and f values. The following stream shows how you can manually set the transformation matrix instead of using Td or T* to create a new line.

|

BT |

Likewise, we can change the matrix’s a and d values to change the font size without using Tf. The next stream scales down the initial font size by 33%, resulting in a 12-point font for the second line.

|

BT |

Of course, the real utility of Tm is to define more than just simple translation and scale operations. It can be used to combine several complex transformations into a single, concise representation. For example, the following matrix rotates the text by 45 degrees and moves it to the middle of the page.

|

BT |

More information about transformation matrices is available from any computer graphics textbook.

Text Painting Operators

Painting operators display text on the page, potentially modifying the current text state or position in the process. The Tj operator that we’ve been using is the core operator for displaying text. The other painting operators are merely convenient shortcuts for common typesetting tasks.

The PDF specification defines four text painting operators:

- <text> Tj: Display the text at the current text position.

- <text> ': Move to the next line and display the text.

- <word-spacing> <character-spacing> <text> ": Move to the next line, set the word and character spacing, and display the text.

- <array> TJ: Display an array of strings while manually adjusting intra-letter spacing.

The Tj Operator

The Tj operator inserts text at the current position and leaves the cursor wherever it ended. Consider the following stream.

|

BT |

Both Tj commands will paint the text on the same line, without a space in between them.

The ' (Single Quote) Operator

The ' (single quote) operator moves to the next line then displays the text. This is the exact same functionality as T* followed by Tj:

|

BT |

Like T*, the ' operator uses the current leading to determine the position of the next line.

The " (Double Quote) Operator

The " (double quote) operator is similar to the single quote operator, except it lets you set the character spacing and word spacing at the same time. Thus, it takes three arguments instead of one.

2 1 (Hello!) " |

This is the exact same as the following.

2 Tw |

Remember that Tw and Tc are often used for justifying paragraphs. Since each line usually needs distinct word and character spacing, the " operator is a very convenient command for rendering justified paragraphs.

|

BT |

This stream uses character and word spacing to justify three lines of text:

Figure 12: Adjusting character and word spacing to create justified lines

The TJ Operator

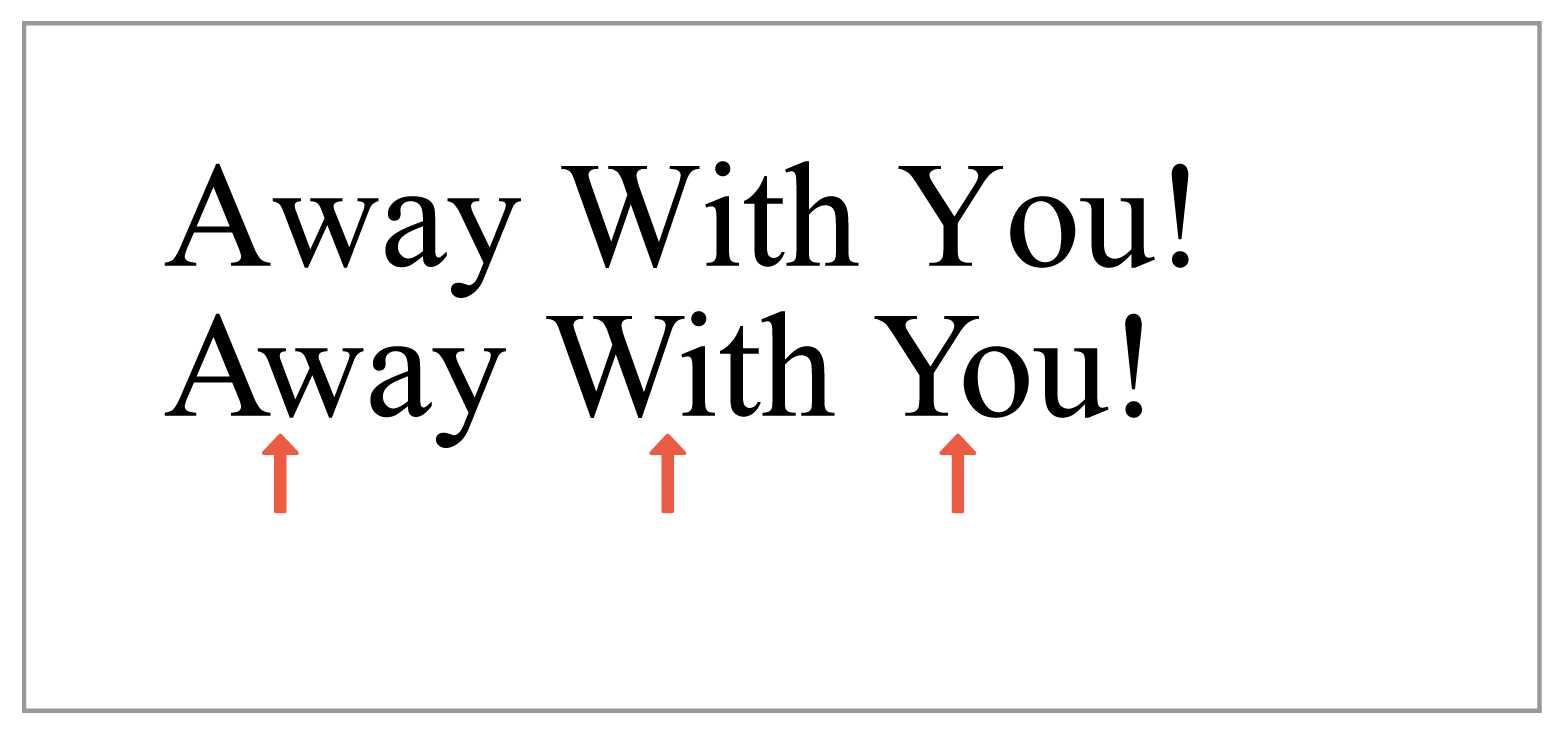

The TJ operator provides even more flexibility by letting you independently specify the space between letters. Instead of a string, TJ accepts an array of strings and numbers. When it encounters a string, TJ displays it just as Tj does. But when it encounters a number, it subtracts that value from the current horizontal text position.

This can be used to adjust the space between individual letters in an entire line using a single command. In traditional typography, this is called kerning.

BT |

This stream uses TJ to kern the “Aw”, “Wi”, and “Yo” pairs. The idea behind kerning is to eliminate conspicuous white space in order to create an even gray on the page. The result is shown in the following figure.

Figure 13: Kerning letter pairs with TJ

Summary

This chapter presented the most common text operators used by PDF documents. These operators make it possible to represent multi-page, text-based documents with a minimum amount of markup. If you’re coming from a typographic background, you’ll appreciate many of the convenience operators like TJ for kerning and " for justifying lines.

You’ll also notice that PDFs do not separate content from presentation. This is a fundamental difference between creating a PDF versus an HTML document. PDFs represent content and formatting at the same time using procedural operators, while other popular languages like HTML and CSS apply style rules to semantic elements. This allows PDFs to represent pixel-perfect layouts, but it also makes it much harder to extract text from a document.

- 1800+ high-performance UI components.

- Includes popular controls such as Grid, Chart, Scheduler, and more.

- 24x5 unlimited support by developers.