CHAPTER 1

Conceptual Overview

We’ll begin with a conceptual overview of a simple PDF document. This chapter is designed to be a brief orientation before diving in and creating a real document from scratch.

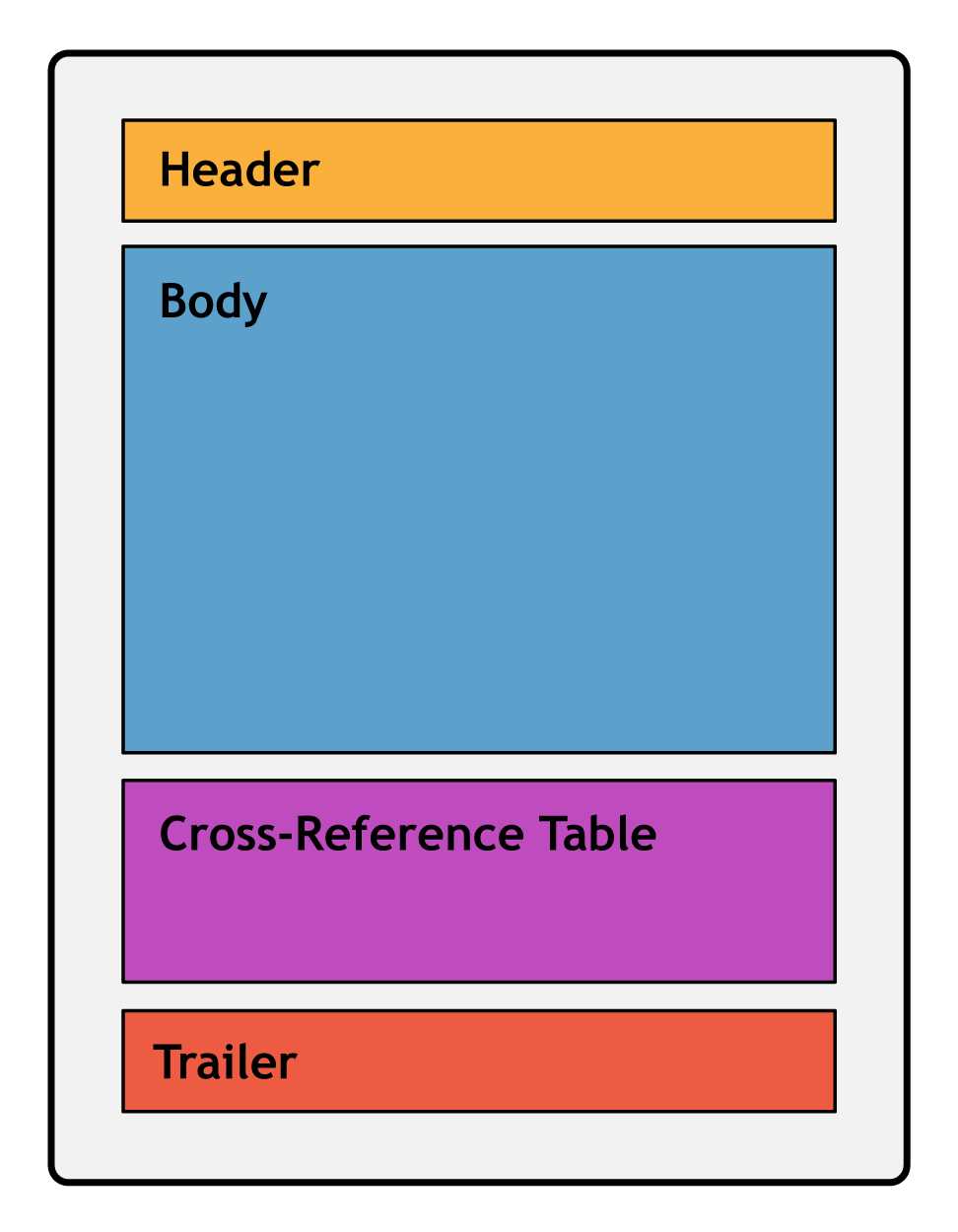

A PDF file can be divided into four parts: a header, body, cross-reference table, and trailer. The header marks the file as a PDF, the body defines the visible document, the cross-reference table lists the location of everything in the file, and the trailer provides instructions for how to start reading the file.

Figure 1: Components of a PDF document

Every PDF file must have these four components.

Header

The header is simply a PDF version number and an arbitrary sequence of binary data. The binary data prevents naïve applications from processing the PDF as a text file. This would result in a corrupted file, since a PDF typically consists of both plain text and binary data (e.g., a binary font file can be directly embedded in a PDF).

Body

The body of a PDF contains the entire visible document. The minimum elements required in a valid PDF body are:

- A page tree

- Pages

- Resources

- Content

- The catalog

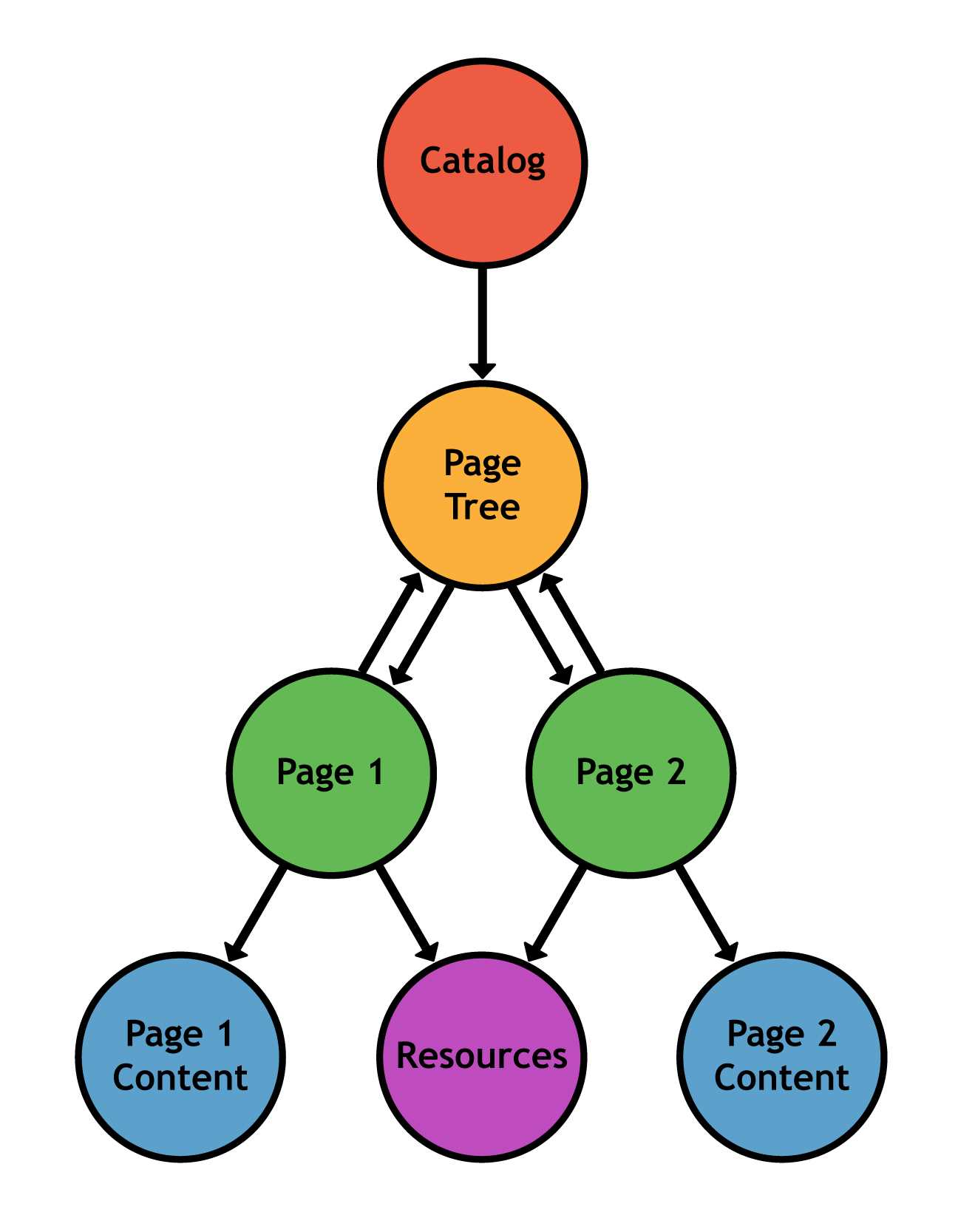

The page tree serves as the root of the document. In the simplest case, it is just a list of the pages in the document. Each page is defined as an independent entity with metadata (e.g., page dimensions) and a reference to its resources and content, which are defined separately. Together, the page tree and page objects create the “paper” that composes the document.

Resources are objects that are required to render a page. For example, a single font is typically used across several pages, so storing the font information in an external resource is much more efficient. A content object defines the text and graphics that actually show up on the page. Together, content objects and resources define the appearance of an individual page.

Finally, the document’s catalog tells applications where to start reading the document. Often, this is just a pointer to the root page tree.

Figure 2: Structure of a document’s body

Cross-Reference Table

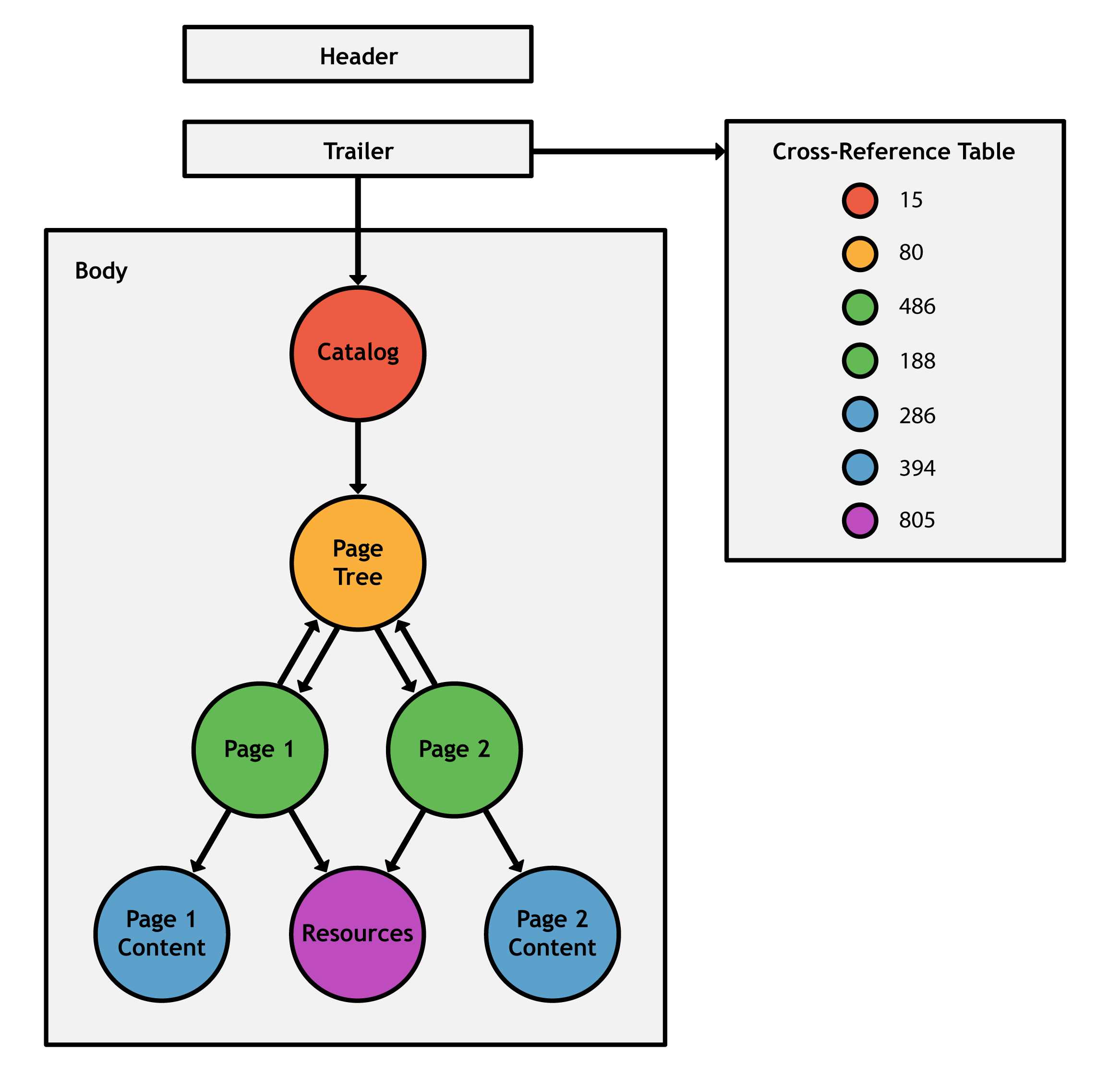

After the header and the body comes the cross-reference table. It records the byte location of each object in the body of the file. This enables random-access of the document, so when rendering a page, only the objects required for that page are read from the file. This makes PDFs much faster than their PostScript predecessors, which had to read in the entire file before processing it.

Trailer

Finally, we come to the last component of a PDF document. The trailer tells applications how to start reading the file. At minimum, it contains three things:

- A reference to the catalog which links to the root of the document.

- The location of the cross-reference table.

- The size of the cross-reference table.

Since a trailer is all you need to begin processing a document, PDFs are typically read back-to-front: first, the end of the file is found, and then you read backwards until you arrive at the beginning of the trailer. After that, you should have all the information you need to load any page in the PDF.

Summary

To conclude our overview, a PDF document has a header, a body, a cross-reference table, and a trailer. The trailer serves as the entryway to the entire document, giving you access to any object via the cross-reference table, and pointing you toward the root of the document. The relationship between these elements is shown in the following figure.

Figure 3: Structure of a PDF document

- 1800+ high-performance UI components.

- Includes popular controls such as Grid, Chart, Scheduler, and more.

- 24x5 unlimited support by developers.