CHAPTER 2

Building a PDF

PDFs contain a mix of text and binary, but it’s still possible to create them from scratch using nothing but a text editor and a program called pdftk. You create the header, body, and trailer on your own, and then the pdftk utility goes in and fills in the binary blanks for you. It also manages object references and byte calculations, which is not something you would want to do manually.

First, download pdftk from PDF Labs. For Windows users, installation is as simple as unzipping the file and adding the resulting folder to your PATH. Running pdftk --help from a command prompt should display the help page if installation was successful.

Next, we’ll manually create a PDF file for use with pdftk. Create a plain text file called hello-src.pdf (this file is available at https://bitbucket.org/syncfusion/pdf-succinctly) and open it in your favorite text editor.

Header

We’ll start by adding a header to hello-src.pdf. Remember that the header contains both the PDF version number and a bit of binary data. We’ll just add the PDF version and leave the binary data to pdftk. Add the following to hello-src.pdf.

%PDF-1.0 |

The % character begins a PDF comment, so the header is really just a special kind of comment.

Body

The body (and hence the entire visible document) is built up using objects. Objects are the basic unit of PDF files, and they roughly correspond to the data structures of popular programming languages. For example, PDF has Boolean, numeric, string, array, and dictionary objects, along with streams and names, which are specific to PDF. We’ll take a look at each type as the need arises.

The Page Tree

The page tree is a dictionary object containing a list of the pages that make up the document. A minimal page tree contains just one page.

|

Objects are enclosed in the obj and endobj tags, and they begin with a unique identification number (1 0). The first number is the object number, and the second is the generation number. The latter is only used for incremental updates, so all the generation numbers in our examples will be 0. As we’ll see in a moment, PDFs use these identifiers to refer to individual objects from elsewhere in the document.

Dictionaries are set off with angle brackets (<< and >>), and they contain key/value pairs. White space is used to separate both the keys from the values and the items from each other, which can be confusing. It helps to keep pairs on separate lines, as in the previous example.

The /Type, /Pages, /Count, and /Kids keys are called names. They are a special kind of data type similar to the constants of high-level programming languages. PDFs often use names as dictionary keys. Names are case-sensitive.

2 0 R is a reference to the object with an identification number of 2 0 (it hasn’t been created yet). The /Kids key wraps this reference in square brackets, turning it into an array: [2 0 R]. PDF arrays can mix and match types, so they are actually more like C#’s List<object> than native arrays.

Like dictionaries, PDF arrays are also separated by white space. Again, this can be confusing, since the object reference is also separated by white space. For example, adding a second reference to /Kids would look like: [2 0 R 3 0 R] (don’t actually add this to hello-src.pdf, though).

Page(s)

Next, we’ll create the second object, which is the only page referenced by /Kids in the previous section.

2 0 obj |

The /Type entry always specifies the type of the object. Many times, this can be omitted if the object type can be inferred by context. Note that PDF uses a name to identify the object type—not a literal string.

The /MediaBox entry defines the dimensions of the page in points. There are 72 points in an inch, so we’ve just created a standard 8.5 × 11 inch page. /Resources points to the object containing necessary resources for the page. /Parent points back to the page tree object. Two-way references are quite common in PDF files, since they make it very easy to resolve dependencies in either direction. Finally, /Contents points to the object that defines the appearance of the page.

Resources

The third object is a resource defining a font configuration.

3 0 obj |

The /Font key contains a whole dictionary, opposed to the name/value pairs we’ve seen previously (e.g., /Type /Page). The font we configured is called /F0, and the font face we selected is /Times-Roman. The /Subtype is the format of the font file, and /Type1 refers to the PostScript type 1 file format.

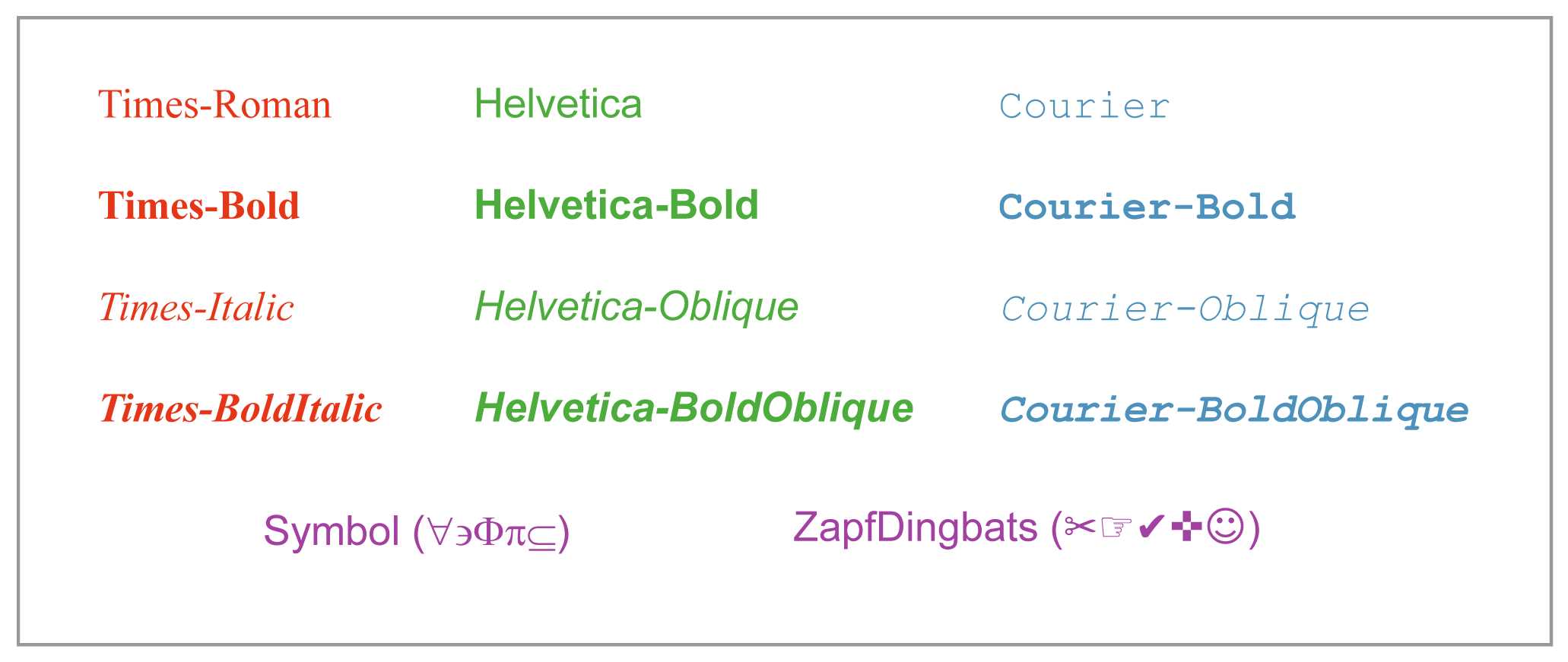

The specification defines 14 “standard” fonts that all PDF applications should support.

Figure 4: Standard fonts for PDF-compliant applications

Any of these values can be used for the /BaseFont in a /Font dictionary. Non-standard fonts can be embedded in a PDF document, but it’s not easy to do manually. We’ll put off custom fonts until we can use iTextSharp’s high-level framework.

Content

Finally, we are able to specify the actual content of the page. Page content is represented as a stream object. Stream objects consist of a dictionary of metadata and a stream of bytes.

4 0 obj |

The << >> creates an empty dictionary. pdftk will fill this in with any required metadata. The stream itself is contained between the stream and endstream keywords. It contains a series of instructions that tell a PDF viewer how to render the page. In this case, it will display “Hello, World!” in 36-point Times Roman font near the top of the page.

The contents of a stream are entirely dependent on context—a stream is just a container for arbitrary data. In this case, we’re defining the content of a page using PDF’s built-in operators. First, we created a text block with BT and ET, then we set the font with Tf, then we positioned the text cursor with Td and finally drew the text “Hello, World!” with Tj. This new operator syntax will be discussed in full detail over the next two chapters.

But, it is worth pointing out that PDF streams are in postfix notation. Their operands are before their operators. For example, /F0 and 36 are the parameters for the Tf command. In C#, you would expect this to look more like Tf(/F0, 36). In fact, everything in a PDF is in postfix notation. In the statement 1 0 obj, obj is actually an operator and the object/generation numbers are parameters.

You’ll also notice that PDF streams use short, ambiguous names for commands. It’s a pain to work with manually, but this keeps PDF files as small as possible.

Catalog

The last section of the body is the catalog, which points to the root page tree (1 0 R).

5 0 obj |

This may seem like an unnecessary reference, but dividing a document into multiple page trees is a common way to optimize PDFs. In such a case, programs need to know where the document starts.

Cross-Reference Table

The cross-reference table provides the location of each object in the body of the file. Locations are recorded as byte-offsets from the beginning of the file. This is another job for pdftk—all we have to do is add the xref keyword.

xref |

We’ll take a closer look at the cross-reference table after we generate the final PDF.

Trailer

The last part of the file is the trailer. It’s comprised of the trailer keyword, followed by a dictionary that contains a reference to the catalog, then a pointer to the cross-reference table, and finally an end-of-file marker. Let’s add all of this to hello-src.pdf.

trailer |

The /Root points to the catalog, not the root page tree. This is important because the catalog can also contain important information about the document structure. The startxref keyword points to the location (in bytes) of the beginning of the cross-reference table. Again, we’ll leave this for pdftk. Between these two bits of information, a program can figure out the location of anything it needs.

The %%EOF comment marks the end of the PDF file. Incremental updates make use of multiple trailers, so it’s possible to have multiple %%EOF lines in a single document. This helps programs determine what new content was added in each update.

Compiling the Valid PDF

Our hello-src.pdf file now contains a complete document, minus a few binary sequences and byte locations. All we have to do is run pdftk to fill in these holes.

pdftk hello-src.pdf output hello.pdf |

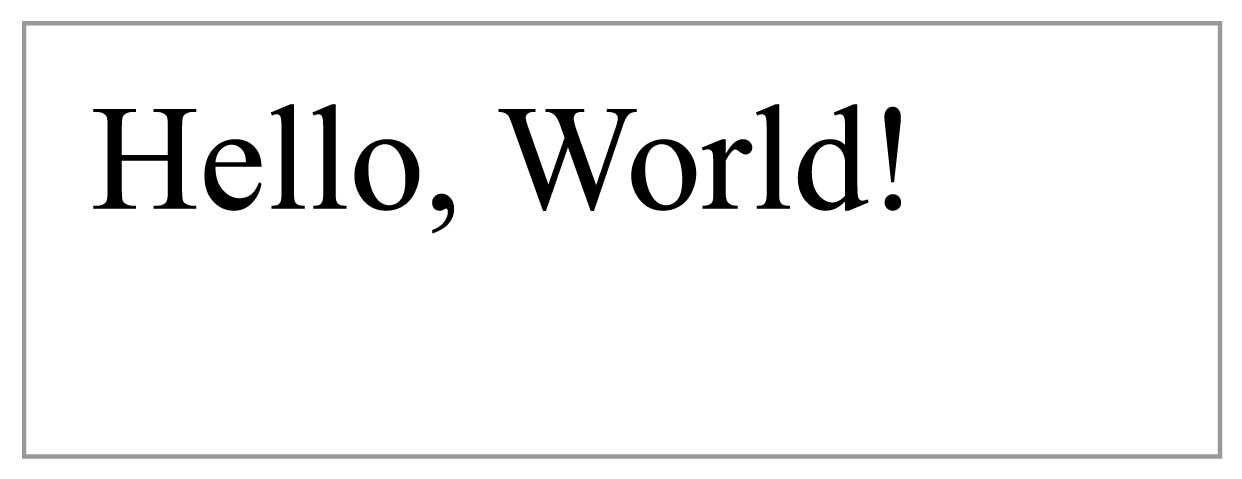

You can open the generated hello.pdf file in any PDF viewer and see “Hello, World!” in 36-point Times Roman font in the upper left corner.

Figure 5: Screenshot of hello.pdf (not drawn to scale)

Let’s take a look at what pdtfk had to add to our source file…

Header Binary

If you open up hello.pdf, you’ll find another line in the header.

%PDF-1.0 |

Again, this prevents programs from processing the file as text. We didn’t have much binary in our “Hello, World!” example, but many PDFs embed complete font files as binary data. Performing a naïve find-and-replace on such a file has the potential to corrupt the font data.

Content Stream Length

Next, scroll down to object 4 0.

4 0 obj |

pdftk added a /Length key that contains the length of the stream, in bytes. This is a useful bit of information for programs reading the file.

Cross-Reference Table

After that, we have the complete xref table.

endobj xref |

It begins by specifying the length of the xref (6 lines), then it lists the byte offset of each object in the file on a separate line. Once a program has located the xref, it can find any object using only this information.

Trailer Dictionary

Also note that pdftk added the size of the xref to the trailer dictionary.

<< |

Finally, pdftk filled in the startxref keyword, enabling programs to quickly find the cross-reference table.

startxref |

Summary

And that’s all there is to a PDF document. It’s simply a collection of objects that define the pages in a document, along with their contents, and some pointers and byte offsets to make it easier to find objects.

Of course, real PDF documents contain much more text and graphics than our hello.pdf, but the process is the same. We got a small taste of how PDFs represent content, but skimmed over many important details. The next chapter covers the text-related operators of content streams.

- 1800+ high-performance UI components.

- Includes popular controls such as Grid, Chart, Scheduler, and more.

- 24x5 unlimited support by developers.