CHAPTER 6

Making Changes

Inserting, Updating, and Deleting

Besides querying, you will also want to make changes. Because NHibernate uses POCOs to represent records in a database, when you need to insert a new record, you start by creating a new instance of a mapped class:

Product p = new Product() { Name = "NHibernate Succinctly", Price = 0 }; |

Then, you tell NHibernate to persist it:

session.Save(p); |

If you have associations that you wish to store along with the root aggregate, you must get a reference to them first:

Post post = new Post(); post.Blog = session.Get<Post>(1); |

In this type of association, what really matters is the foreign key; you might as well load a proxy instead, which has the advantage of not actually going to the database:

//or get a proxy, no need to go to the database if we only need the foreign key post.Blog = session.Load<Post>(1); |

In this case, however, if the referenced entity does not exist, an exception will be thrown when NHibernate attempts to save the root aggregate.

In the case of bidirectional associations, it is recommended that you fill both sides of the relationship if you are going to work with the entities immediately, for coherence:

For your convenience, you can add a simple method to the Blog class for hooking the two endpoints:

public void AddPost(Post post) { post.Blog = this; this.Posts.Add(post); } |

Depending on your session configuration, this may or not be all that it takes. (More on this in the next section, Flushing Changes.)

NHibernate implements something called first-level cache in its ISession. What this means is, all of the entities that it loads or are marked for saving are stored in a memory cache. For each of these entities, when it is loaded, NHibernate takes a snapshot of its initial state and stores it internally. When it is time for persisting changes to the database, NHibernate will check all of the entities present in its first-level cache for the current values of their properties and will detect those entities whose properties have changed. This is called change tracking, and such entities are said to be dirty. A dirty session contains at least one dirty entity.

Because change tracking is automatic, there is normally no need to explicitly update an entity. However, the ISession has an Update method that you can call to force an update:

session.Update(p); |

And, if you need to delete an entity from the database, you call the session’s Delete method upon this entity:

session.Delete(p); |

Finally, when you have an entity with a loaded collection (a one-to-many or many-to-many) and you want to remove all of its elements, instead of iterating one by one and calling Delete, you can just call Clear on the collection property:

Blog blog = session.Get<Blog>(1); blog.Posts.Clear(); |

NHibernate will then issue a single DELETE statement for all of the child records.

Pay attention: You can only call Delete on a tracked entity; that is, one that was either loaded from the database or explicitly added to it, by calling Save. After you do it, you should no longer access this entity instance because nothing you can do with it will prevent it from being deleted.

NHibernate will store, update or delete each entity in the database by issuing appropriate SQL commands whenever the session is flushed. In a nutshell, what this means is:

- New entities need to be marked explicitly for saving, by calling Save.

- Existing tracked entities will detect changes made upon them automatically. There is no need to explicitly mark them for updating; that is, no need to call any method.

- If you are not sure if an entity was already saved, you can call SaveOrUpdate.

- You delete a tracked entity by calling Delete explicitly on it.

Flushing Changes

When does NHibernate know that it is time to persist all changes from the first-level cache to the database (in other words, flush)? It depends on the flush mode (the FlushMode property) of the current ISession. It is the FlushMode that controls when it happens. The possible options are:

- Always: NHibernate will persist dirty entities before issuing any query and immediately after the Save or Delete methods are called.

- Auto: NHibernate will send changes to the database if a query is being issued for some entity and there are dirty entities of the same type.

- Commit: Flushing will only occur when the current transaction is committed.

- Never: You need to call Flush explicitly on the current ISession.

- Unspecified: The default, identical to Auto.

Some notes:

- You should generally avoid Always as it may slow down NHibernate because it will need to check the first-level cache before issuing any query.

- Never is also something to avoid because it is possible that you could forget to call Flush and all changes will be lost.

- Commit and Auto are okay. Commit is even better because it forces you to use transactions (which is a best practice).

Updating Disconnected Entities

What happens if you have an entity that was loaded in a different session and you want to be able to change or delete it in another session? This other session does not know anything about this entity; it is not in its first-level cache and so, from its point of view, it is an untracked or disconnected entity.

You have two options:

- Update the memory entity with the current values for its associated record in the database and then apply changes:

|

using (ISession session = sessionFactory.OpenSession()) { //load some entity and store it somewhere with a greater scope than this session product = session.Query<Product>().First(); }

using (ISession session = sessionFactory.OpenSession()) { //retrieve current values from the database before making changes product = session.Merge<Product>(product); product.Price = 10; session.Flush(); } |

- Force the current values of the entity to be persisted, ignoring the current values in the database:

using (ISession session = sessionFactory.OpenSession()) { //save current entity properties to the database without an additional select product.Price = 10; session.SaveOrUpdateCopy(product); session.Flush(); } |

Removing from the First-Level Cache

Long-lived NHibernate sessions will typically end up with many entities to track—those loaded from queries. This may eventually cause performance problems because, when the time comes for flushing, the session has a lot of instances and values to check for dirtiness.

When you no longer need to track an entity, you can call ISession.Evict to remove it from cache:

session.Evict(product); |

Or, you can clear the entire session:

session.Clear(); |

Tip: This will lose all tracked entities as well as any changes they might have, so use with caution.

Another option would be to mark the entity as read-only, which means its state won’t be looked at when the session is flushed:

session.SetReadOnly(product, true); |

Note: At any later stage, if the entity is still being tracked, you can always revert it by calling SetReadOnly again with a false parameter.

Executable HQL

NHibernate also supports bulk DML operations by using the HQL API. This is called executable HQL and inserts, updates, and deletes are supported:

|

Int32 updatedRecords = session.CreateQuery("update Product p set p.Price = p.Price * 2") .ExecuteUpdate(); Int32 deletedRecords = session.CreateQuery("delete from Product p where p.Price = :price") .SetParameter("price", 0).ExecuteUpdate(); //delete from query Int32 deletedRecords = session.Delete("from Product p where p.Price = 0"); //insert based on existing records Int32 insertedRecords = session.CreateQuery( "insert into Product (ProductId, Name, Price, Specification) select p.ProductId * 10, p.Name + ' copy', p.Price * 2, p.Specification from Product p").ExecuteUpdate(); |

NHibernate will not make changes to entities that exist in the first-level cache; that is, if you have loaded an entity and then either modify or delete it by using HQL. This entity will not know anything about it. If you have deleted it with HQL and you try to save it later, an error will occur because there is no record to update.

Pay attention to this: You normally don’t have to think about identifier generation patterns. But, if you are going to insert records by using HQL and you don’t use the IDENTITY generation pattern, you need to generate the ids yourself. In this example, we are creating them from entries that already exist because you can only insert in HQL from records returned from a select.

Detecting Changes

The IsDirty property of the ISession will tell you if there are either new entities marked for saving, entities marked for deletion, or loaded entities that have changed values for some of their properties—as compared to the ones they had when loaded from the database.

You can examine entities in the first-level cache yourself by using the NHibernate API:

This extension method may come in handy if you have loaded a lot of entities and you need to find a particular one. You can look it up in the first-level cache first before going to the database. Or you can find entities with a particular state such as Deleted, for instance.

Because NHibernate stores the original values for all mapped properties of an entity, you can look at them to see what has changed:

Cascading Changes

Entities with references to other entities, either direct references (a property of the type of another entity) or collections can propagate changes made to themselves to these references. The most obvious cases are:

- When a root entity is saved, save all of its references if they are not already saved (insert records in the corresponding tables).

- When a parent entity is deleted, delete all of its child entities (delete records from the child tables that referenced the parent record).

- When an entity that is referenced by other entities is deleted, remove its reference from all of these entities (set the foreign key to the main record to NULL).

In NHibernate’s terms, this is called cascading. Cascade supports the following options which may be specified either in mapping by code, XML or attributes:

- Detach/evict: The child entity is removed (evicted) from the session when its parent is also evicted, usually by calling ISession.Evict.

- Merge/merge: When a parent entity is merged into the current session, usually by ISession.Merge, children are also merged.

- Persist/save-update: When a root entity is about to be saved or updated, its children are also saved or updated.

- ReAttach/lock: When a parent entity is locked, also lock its children.

- Refresh/refresh: When a parent entity is refreshed, also refresh its children.

- Remove/delete: Deletes the child entity when its parent is deleted.

- None/none: Do nothing, this is the default.

- All/all: The same as Persist and Remove; all child entities that are not saved are saved, and if the parent is deleted, they are also deleted.

- DeleteOrphans/delete-orphan: if a child entity of a one-to-many relation no longer references the original parent entity, or any other, remove it from the database.

- All and DeleteOrphans/all-delete-orphan: the combined behavior of All and DeleteOrphans.

Cascading can be tricky. Some general guidelines:

- For entities that depend on the existence of another entity, use DeleteOrphans because, if the relation is broken (you set the property to null), the entity cannot exist by itself and must be removed.

- For collections, you normally would use All (possibly together with DeleteOrphans). If you want all of the entities in the collection to be saved and deleted whenever their parent is, or use Persist if you don’t want them to be deleted with their parent but want them to be saved automatically.

- For many-to-one references you normally won’t want Delete because usually the referenced entity should live longer than the entities that reference it; use Persist instead.

To apply cascading by code, use this example (same mapping as in section Mapping by Code):

With XML, it would look like this (again, same mapping as in XML Mappings):

<hibernate-mapping namespace="Succinctly.Model" assembly="Succinctly.Model" xmlns="urn:nhibernate-mapping-2.2"> <class name="Blog" lazy="true" table="`BLOG`"> <!-- … -> <many-to-one name="Owner" column="`USER_ID`" not-null="true" lazy="no-proxy" cascade="save-update"/> <list cascade="all-delete-orphan" inverse="true" lazy="true" name="Posts"> <!-- … -> </list> </class> </hibernate-mapping> <hibernate-mapping namespace="Succinctly.Model" assembly="Succinctly.Model" xmlns="urn:nhibernate-mapping-2.2"> <class name="Post" lazy="true" table="`POST`"> <!-- … -> <set cascade="all" lazy="false" name="Tags" table="`TAG`" order-by="`TAG`"> <!-- … -> </set> <set cascade="all-delete-orphan" inverse="true" lazy="true" name="Attachments"> <!-- … -> </set> <bag cascade="all-delete-orphan" inverse="true" lazy="true" name="Comments"> <!-- … -> </bag> </class> </hibernate-mapping> |

And finally, with attributes (see Attribute Mappings for the full mapping):

|

{ //… [ManyToOne(0, Column = "user_id", NotNull = true, Lazy = Laziness.NoProxy, Name = "Owner", Cascade = "save-update")] public virtual User Owner { get; set; } //… [List(0, Cascade = "all-delete-orphan", Lazy = CollectionLazy.True, Inverse = true, Generic = true)] public virtual IList<Post> Posts { get; protected set; } } public class Post { [Set(0, Name = "Tags", Table = "tag", OrderBy = "tag", Lazy = CollectionLazy.False, Cascade = "all" , Generic = true)] public virtual Iesi.Collections.Generic.ISet<String> Tags { get; protected set; } [Set(0, Name = "Attachments", Inverse = true, Lazy = CollectionLazy.True, Cascade = "all-delete-orphan", Generic = true)] public virtual Iesi.Collections.Generic.ISet<Attachment> Attachments { get; protected set; } [Bag(0, Name = "Comments", Inverse = true, Lazy = CollectionLazy.True, Generic = true, Cascade = "all-delete-orphan")] public virtual IList<Comment> Comments { get; protected set; } } |

An example is in order. Imagine that your entities are not using cascade and you have to save everything by hand:

Whereas, if you have cascading set for the Owner and Posts properties of the Blog class, you only need to call Save once, for the root Blog instance, because all of the other entities are accessible (and cascaded) from it:

session.Save(b); session.Flush(); |

Should you ever need to delete a Blog instance, all of its Posts, related Comments and Attachments will be deleted at the same time but not its Owner.

session.Delete(b); session.Flush(); |

Transactions

As you know, when changing multiple records at the same time, especially if one change depends on the other, we need to use transactions. All relational databases support transactions, and so does NHibernate.

Transactions in NHibernate come in two flavors:

- NHibernate-specific transactions, which are useful when they are clearly delimited; that is, we know when they should start and terminate and should only affect NHibernate operations.

- .NET ambient transactions, for when we have to coordinate access to multiple databases simultaneously or enlist in existing transactions that may even be distributed.

With NHibernate, you really should have a transaction whenever you may be making changes to a database. Remember that not all changes are explicit. For example, a change in a loaded entity may cause it to be updated on the database. If you use transactions, you won’t have any bad experiences. Whenever you use transactions, set the flush mode of the session to the appropriate value:

This will cause NHibernate to only send changes to the database when (and only if) the current transaction is committed.

The transaction API can be used like this:

All operations performed on an ISession instance that is running under a transaction are automatically enlisted in it; this includes explicit saves, updates and deletes, automatic updates due to dirty properties, custom SQL commands, and executable HQL queries.

You can check the current state of a transaction and even check if one was started:

The alternative to this API is System.Transactions, .NET’s standard transaction API:

Both NHibernate and System transactions allow specifying the isolation level:

ITransaction tx = session.BeginTransaction(System.Data.IsolationLevel.Serializable); new TransactionScope(TransactionScopeOption.Required, new TransactionOptions() { IsolationLevel = System.Transactions.IsolationLevel.Serializable }); |

Just remember this:

- Use them at all times!

- Either with NHibernate or System transactions, always create them in a using block so that they are automatically disposed.

- Set the session’s flush mode to Commit to avoid unnecessary trips to the database.

- Make sure you call Commit (on NHibernate transactions) or Complete (on System ones) when you are done with the changes and you want to make them permanent.

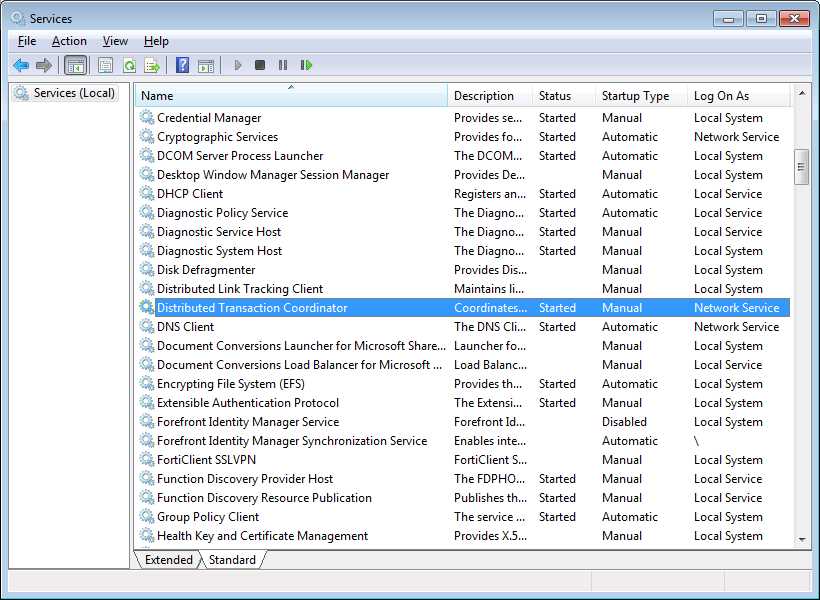

- If you are going to access multiple databases simultaneously in a System transaction, you must start the Distributed Transaction Coordinator service or else you may get unexpected exceptions when you access the second database:

- Distributed Transaction Coordinator Service

Pessimistic Locking

At times, there may be a need to lock one or more records in a table so that nobody else can make modifications to them behind our back. This is called concurrency control. Different databases use different mechanisms for this but NHibernate offers an independent API. Locking involves a lock mode, for which the following values exist:

Mode | Description |

Force | Similar to Upgrade but causes a version increment, if the entity is versioned |

None | Not used |

Read | When an entity is read without specifying a LockMode |

Upgrade | Switch from not locked to locked; if the record is already locked, will wait for the other lock to be released |

UpgradeNoWait | Same as Upgrade but, in case the record is already locked, will return immediately instead of waiting for the other lock to be released (but the lock mode will remain the same) |

Write | When an entity was inserted from the current session |

Locking must always be called in the context of a transaction. NHibernate always synchronizes the lock mode of a record in the database with its in-memory (first-level cache) representation.

For locking a single record upon loading, we can pass an additional parameter to the Get method:

Which will result in the following SQL in SQL Server:

SELECT product0_.product_id, product0_.name, product0_.specification, product0_.price FROM product product0_ WITH (UPDLOCK, ROWLOCK) WHERE product0_.product_id = 1 |

But we can also lock a record after loading:

session.Lock(p, LockMode.Upgrade); |

And it will result in this SQL being sent (notice that it is not bringing the columns):

SELECT product0_.product_id, FROM product product0_ WITH (UPDLOCK, ROWLOCK) WHERE product0_.product_id = 1 |

And locking the results of a query (HQL, Criteria, and Query Over) is possible, too:

For getting the lock state of a record:

LockMode mode = session.GetCurrentLockMode(p); |

Whenever the lock mode is Upgrade, UpgradeNoWait, Write or Force, you know the record is being locked by the current session.

Tip: Generally speaking, locking at the record level is not scalable and is not very useful in the context of web applications which are, by nature, disconnected and stateless. So you should generally avoid it in favor of optimistic locking (coming up next). At the very least, do limit the number of records you lock to the very minimum amount possible.

Optimistic Concurrency

Optimistic concurrency is a process for handling concurrency which doesn’t involve locking. With optimistic locking, we assume that no one is locking the record and we can compare all or some of the previously loaded record’s values with the values currently in the database to see if something has changed (when an UPDATE is issued). If the UPDATE affects no records, we know that something indeed has changed.

NHibernate offers several optimistic concurrency possibilities:

- None: No optimistic locking will be processed, usually known as “last one wins.” This is the default.

- Dirty: All dirty (meaning, changed) mapped properties are compared with their current values in the database.

- All: All mutable mapped properties are compared with the current values.

- Versioned: One column of the table is used for comparison.

When we use versioning, we also have several strategies for obtaining and updating the version column:

- Using a database-specific mechanism such as SQL Server’s TIMESTAMP/ROWVERSION (http://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/library/ms182776.aspx) or Oracle’s ORA_ROWSCN (http://docs.oracle.com/cd/B19306_01/server.102/b14200/pseudocolumns007.htm); this requires no work from NHibernate other than loading the current value.

- Using an integer number for the version which NHibernate must update explicitly.

- Using a date and time which can either be obtained from the database or from .NET which NHibernate is also responsible for updating.

No strategy is the default. If we want to have Dirty or All, we need to configure it on an entity-by-entity basis.

In XML:

<hibernate-mapping namespace="Succinctly.Model" assembly="Succinctly.Model" xmlns="urn:nhibernate-mapping-2.2"> <class name="Blog" lazy="true" table="`BLOG`" optimistic-lock="dirty" dynamic-update="true"> <!-- … --> </class> </hibernate-mapping> |

And attributes:

[Class(Table = "blog", Lazy = true, OptimisticLock = OptimisticLockMode.Dirty, DynamicUpdate = true)] public class Blog { //… } |

Unfortunately, as of now, mapping by code does not allow setting the optimistic lock mode. But you can still achieve it by code on the Configuration instance:

cfg.GetClassMapping(typeof(Blog)).OptimisticLockMode = Versioning.OptimisticLock.Dirty; cfg.GetClassMapping(typeof(Blog)).DynamicUpdate = true; |

In this case, a change to a property in a Product instance would lead to the following SQL being issued (in real life, with parameters instead of numbers):

UPDATE product SET price = 10 WHERE product_id = 1 AND price = 5 |

As you can see, the “price = 5” condition is not strictly required but NHibernate is sending it because of the optimistic lock mode of Dirty and because the Price property was changed.

Like I said, instead of Dirty, you can use All. In either case, you must also add the dynamic-update attribute; it is a requirement. And what it means is, instead of issuing a SET for each of the mapped columns, it will only issue one for the columns whose values have changed. You need not worry about it; no additional columns in the database or properties in the model need to be added.

For the same updated Product instance, when using All as the optimistic lock mode, the SQL would be:

UPDATE product SET price = 10 WHERE product_id = 1 AND price = 5 AND specification = /* ... */ AND picture = /* ... */ |

As you can see, in this case all columns are compared, which may be slightly slower.

As for versioned columns, we need to add a new property to our entity for storing the original version. Its type depends on what mechanism we want to use. For example, if we want to use SQL Server’s ROWVERSION, we would have a property defined like this:

public virtual Byte[] Version { get; protected set; } |

And we would map it by code, like this (in a ClassMapping<T> or ModelMapper class):

this.Version(x => x.Version, x => { x.Column(y => { y.NotNullable(true); y.Name("version"); y.SqlType("ROWVERSION"); }); x.Insert(false); x.Generated(VersionGeneration.Always); x.Type(NHibernateUtil.BinaryBlob as IVersionType); }); |

We have to tell NHibernate to always have the database generate the version for us, to not insert the value when it is inserting a record for our entity, to use the SQL type ROWVERSION when creating a table for the entity, and to use the NHibernate BinaryBlobType, a type that allows versioning, for handling data for this column.

With attributes, this is how it would look:

[Version(0, Name = "Version", Column = "version", Generated = VersionGeneration.Always, Insert = false, TypeType = typeof(BinaryBlobType))] [Column(1, SqlType = "ROWVERSION")] public virtual Byte[] Version { get; protected set; } |

And finally, in XML:

<class name="Product" lazy="true" table="`product`"> <!-- ... --><version name="Version" column="version" generated="always" insert="false" type="BinaryBlob"/> <!-- ... --> </class> |

Whereas, for Oracle’s ORA_ROWSCN, the property declaration would be instead:

public virtual Int64[] Version { get; protected set; } |

And its fluent mappings:

this.Version(x => x.Version, x => { x.Column(y => { y.NotNullable(true); y.Name("ora_rowscn"); }); x.Insert(false); x.Generated(VersionGeneration.Always); }); |

Attribute mappings:

[Version(Name = "Version", Column = "ora_rowscn", Generated = VersionGeneration.Always, Insert = false)] public virtual Int64[] Version { get; protected set; } |

And, finally, XML:

<class name="Product" lazy="true" table="`product`"> <!-- ... --> <version name="Version" column="ora_rowscn" generated="always" insert="false" /> <!-- ... --> </class> |

Database-specific strategies are great because they leverage each database’s optimized mechanisms, and version columns are automatically updated. But they render our code less portable and require an additional SELECT after each UPDATE in order to find out what value the record has.

For database-independent strategies, we can choose either a number or a date/time as the version column. For a number (the default versioning strategy), we add an integer property to our class:

public virtual Int32[] Version { get; protected set; } |

And we map it by code:

this.Version(x => x.Version, x => { x.Column(y => { y.NotNullable(true); y.Name("version"); }); }); |

By XML:

<class name="Product" lazy="true" table="`product`"> <!-- ... --> <version name="Version" column="version" /> <!-- ... --> </class> |

Or by attributes:

[Version(Name = "Version", Column = "version")] public virtual Int32[] Version { get; protected set; } |

If we instead want to use a date/time, we need to add a type attribute and change the property’s type:

public virtual DateTime[] Version { get; protected set; } |

And we need to update the mapping to use a TimestampType:

this.Version(x => x.Version, x => { x.Column(y => { y.NotNullable(true); y.Name("version"); }); x.Type(NHibernateUtil.Timestamp as IVersionType); }); |

By XML:

<class name="Product" lazy="true" table="`product`"> <!-- ... --> <version name="Version" column="version" type="timestamp"/> <!-- ... --> </class> |

And attributes:

[Version(Name = "Version", Column = "version", TypeType = typeof(TimestampType))] public virtual DateTime[] Version { get; protected set; } |

Once you update an optimistic locking strategy, your UPDATE SQL will look like this (with parameters instead of literals, of course):

UPDATE product SET price = 10, version = 2 WHERE product_id = 1 AND version = 1 |

Generally speaking, whenever we update an entity, its version will increase, or in the case of date and time properties, will be set as the current timestamp. But we can specify on a property-by-property basis if changes made upon them should be considered when incrementing the version of the entity. This is achieved by the property’s optimistic lock attribute as you can see in XML:

<property name="Timestamp" column="`TIMESTAMP`" not-null="true" optimistic-lock="false" /> |

Code:

this.Property(x => x.Timestamp, x => { x.Column("timestamp"); x.NotNullable(true); x.OptimisticLock(false); }); |

And attributes mapping:

[Property(Name = "Timestamp", Column = "timestamp", NotNull = true, OptimisticLock = false)] public virtual DateTime Timestamp { get; set; } |

Whenever the number of updated records is not what NHibernate expects, due to optimistic concurrency checks, NHibernate will throw a StaleStateException. When this happens, you have no alternative but to refresh the entity and try again.

Optimistic locking is very important when we may have multiple, simultaneous accesses to database tables and when explicit locking is impractical. For example, with web applications. After you map some entity using optimistic locking, its usage is transparent. If, however, you run into a situation in which the data on the database does not correspond to the data that was loaded for some entity, NHibernate will throw an exception when NHibernate flushes it.

As for its many options, I leave you with some tips:

- In general, avoid database-specific strategies, as they are less portable and have worse performance.

- Use Dirty or All optimistic locking modes when you do not need a column that stores the actual version.

- Use date/time versions when knowing the time of the record’s last UPDATE is important to you and you don’t mind adding an additional column to a table.

- Finally, choose numeric versioning as the most standard case.

When using Executable HQL for updating records, you can use the following syntax for updating version columns automatically, regardless of the actual strategy:

Int32 updatedRecords = session .CreateQuery("update versioned Product p set p.Price = p.Price * 2").ExecuteUpdate(); |

Tip: Never update a version column by hand. Use protected setters to ensure this.

Batch Insertions

NHibernate is no ETL tool, which means it wasn’t designed for bulk loading of data. Having said that, this doesn’t mean it is impossible to do. However, the performance may not be comparable to other solutions. Still, there are some things we can do to help.

First, in modern databases, there is no need to insert one record at a time. Typically, these engines allow batching, which means that several records are inserted at the same time, thus minimizing the number of roundtrips. As you can guess, NHibernate supports insert batching; you just have to tell it to use it. Using loquacious configuration, we set the BatchSize and Batcher properties:

Configuration cfg = BuildConfiguration() .DataBaseIntegration(db => { //... db.Batcher<SqlClientBatchingBatcherFactory>(); db.BatchSize = 100; }) |

Tip: You need to add a reference to the NHibernate.AdoNet namespace for the SqlClientBatchingBatcherFactory class.

Or, if you prefer to use XML configuration, add the following properties to your App/Web.config:

<session-factory> <!-- ... --> <property name="adonet.factory_class"> NHibernate.AdoNet.SqlClientBatchingBatcherFactory, NHibernate</property> <property name="adonet.batch_size">100</property> </session-factory> |

Batcher factories exist for SQL Server and Oracle; the one for the latter is called OracleDataClientBatchingBatcherFactory. It is certainly possible to implement them for other engines and some people, in fact, have. It is a matter of implementing IBatcherFactory and IBatcher. Granted, it’s not simple but it’s still possible.

What the BatchSize/batch-size property means is, when inserting records, NHibernate should insert records 100 at a time instead of one by one.

For example, try the following example with and without batching enabled (set BatchSize to 0 and remove the Batcher declaration in the configuration):

NHibernate has a lightweight alternative to the regular sessions called stateless sessions. Stateless sessions are built from a session factory and have some drawbacks:

- No first-level cache, which means stateless sessions do not know what changed.

- No cascading support.

- No lazy loading support.

- Fine-grained control over inserts and updates.

- No flushing; commands are sent immediately.

- No events are raised.

The same example with stateless sessions would look like this:

- 1800+ high-performance UI components.

- Includes popular controls such as Grid, Chart, Scheduler, and more.

- 24x5 unlimited support by developers.