CHAPTER 12

Bootstrapping

In this chapter, we start getting into the good stuff: we’re about to open the bonnet (or the hood, depending on where you live) and start tuning and tinkering around with Nancy's internals.

Just what is a bootstrap? It has nothing to do with that client-side framework everyone uses for making nice, web-based user interfaces. Here is its definition according to the dictionary:

Figure 28: Dictionary definition of bootstrap (Courtesy of Dictionary.com)

For our use, bootstrapping (or just booting) is starting up a piece of software or hardware prior to it being in a state that is then useable by an end user.

Where Nancy is concerned, the bootstrap process is the sequence of events that Nancy goes through when an application using it is first run, up to the point where it's ready to start servicing requests sent to it.

A custom bootstrapper, therefore, is a class defined by the application developer and executed at an appropriate place during this startup, allowing the developer to provide customizations and extra startup procedures for use by the Nancy kernel itself.

It's a bit like buying a used car, then tweaking the engine to give it more performance, adding new interiors and a new radio, and providing other improved features to stamp your own identity on the vehicle. By writing and using a custom bootstrapper, you get to make Nancy do all sorts of out-of-the-box extra stuff.

In many cases, configuration of the many extra modules that Nancy has available can only be done in a bootstrapper. Many of the more advanced things you may want to enable can only be done in this way. However, in general, you will find that in some cases, you might not even have to know a bootstrapper exists in order to use a lot of the built-in functionality Nancy has.

Nancy uses the bootstrapper in two ways. It uses it as a method to expose to you the developer—all the hooks, configuration options, and other user-level stuff that can be overridden to the developer working with the framework.

Secondly, Nancy uses the bootstrapper to perform tasks such as configuring the built-in IoC container, TinyIOC, and provides start up points for you to register your own assemblies, in effect wrapping the whole IoC (Inversion of Control) in a domain-specific language (in the words of the NancyFX Wiki).

IoC container

Before we go further, I'd like to introduce another of Nancy's hidden features here: it's built-in IoC container.

For those who are new to the concept, IoC is a method of injecting dependencies into a running code base as required without needing to create new objects. It's an architecture pattern that helps to keep applications composed and easy to manage. It also aids with testing and creating mock objects for functionality that has not been added yet.

What it means for Nancy-based applications is that Nancy will try to satisfy any dependencies required by your code automatically. For example, imagine you had the following route module:

Code Listing 55

using System; using System.Collections.Generic; using System.IO; using Nancy; using Nancy.Responses; namespace nancybook.modules { public class BaseRoutes : NancyModule { private FakeDatabase _db; public BaseRoutes() { Get[@"/"] = _ => { var _db = new FakeDatabase(); var myList = db.GetHashCode(); return View["myview", myList]; }; } } } |

This is a simple example, but an important one.

In this module, your FakeDatabase is known as a concrete dependency. That is, it's very hard to manage, and very hard to change. Imagine you had 20 route modules, all with about 10 URLs defined in them, and that each one used that same database library, and had to create a new instance each time it was used.

Now imagine you needed to change that database library from FakeDatabase to RealDatabase. You suddenly realize just how much work that's going to involve.

An IoC container elevates that considerably. Take the next example:

Code Listing 56

using System; using System.Collections.Generic; using System.IO; using Nancy; using Nancy.Responses; namespace nancybook.modules { public class BaseRoutes : NancyModule { private readonly FakeDatabase _db; public BaseRoutes(FakeDatabase db) { _db = db; Get[@"/"] = _ => { var myList = _db.GetHashCode(); return View["myview", myList]; }; } } } |

This is exactly the same as the previous example, except now it uses IoC to manage the database library. If I was using this in 10 places in my module, all I'd have to do is change two instances of it: once for the private variable, and once in the constructor parameter.

My IoC library would handle the rest, including making sure I had a new instance connected to _db right when I wanted to use it.

It also means that should I wish to, within the Nancy bootstrapper, I can override the automatic settings for this IoC container, and tell Nancy that when something wants to use a FakeDatabase object, you should instead give it a RealDatabase object. This reduces those two changes in each route module to just one global change in a single class.

Nancy can use several different IoC containers, and has NuGet packages to enable them. If you already use one of these more popular ones, then you might want to consider using it. However, if you haven’t used IoC before, but like the idea of how it works, the built-in container more than suffices.

Let’s turn our attention back to using the Bootstrapper class.

The default bootstrapper

All this talk of overrides and custom classes might have you thinking that implementing a Nancy bootstrapper is a lot of hard work, and not worth the effort.

This would be very true if you had to implement the entire thing from scratch every time you needed to use one. However, the Nancy team has thought ahead and provided you with a class called DefaultNancyBootStrapper to abstract from.

All you have to do to get a custom bootstrap class (that implements everything Nancy needs, and allows you to use the bits you need to) is the following:

Code Listing 57

using System.Text; using Nancy; using Nancy.Bootstrapper; namespace nancybook { public class CustomBootstrapper : DefaultNancyBootstrapper { } } |

Within the body of this class, you can now create overridden methods to make your own custom implementations of any functionality you need. For example, let's imagine that you had some kind of external data repository library, and this library may use some form of generics, allowing you to use different data objects with the same base class. You can easily declare an interface for your base class, wrap that up in a concrete implementation, and then tell your IoC container what to look for:

Code Listing 58

using System.Text; using demodata; using demodata.entities; using Nancy; using Nancy.Authentication.Forms; using Nancy.Bootstrapper; using Nancy.Conventions; using Nancy.Session; using Nancy.TinyIoc; namespace nancybook { public class CustomBootstrapper : DefaultNancyBootstrapper { protected override void ConfigureApplicationContainer(TinyIoCContainer container) { base.ConfigureApplicationContainer(container); container.Register<IDataProvider<Genre>>(new GenreDataProvider()); container.Register<IDataProvider<Album>>(new AlbumDataProvider()); container.Register<IDataProvider<Track>>(new TrackDataProvider()); container.Register<IDataProvider<Artist>>(new ArtistDataProvider()); } } } |

You can also use the IoC overrides to make singletons and other instances. In my demo application, for example, I present a small but simple way of providing a low-key form of request caching, and the class I use to manage the cache is set up to be instantiated in the service as a singleton. Another scenario where a singleton class is useful is when writing Nancy services that monitor and provide a web interface to hardware.

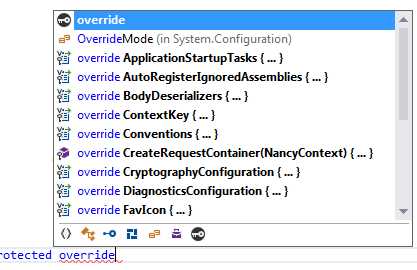

All of these things and more are configured in the ConfigureApplicationContainer override. There are many other too; if you start typing “protected override…” in your class, and pause, IntelliSense should list them all for you, along with their signatures:

Figure 29: IntelliSense showing the available bootstrapper overrides

In reality, you'll commonly only use a few different overrides. In my example app, for instance, I've used RequestStartup to set up forms authentication, ConfigureRequestContainer to configure my IUserMapper, ConfigureApplicationContainer to register my external IoC dependencies, ConfigureConventions to set up static file folders for my web application, and ApplicationStartup to add an error-handling pipeline.

You'll find that the naming is deliberate, too: for overrides that use “Request” in the name, Nancy will call these hooks on a request basis. These are the usual places where you'd look for things like request authentication, caching, or checking that a given header is available.

Anything that has “Application” in the name is generally specific to the application as a whole, and will be called when that app is started. In the case of a standalone service, that would be when the app is physically started using the service control manager, or when it's run from the Windows desktop by clicking on it. For applications that are hosted using ASP.NET and IIS7, then this will get called whenever the server’s app-pool is recycled.

A bootstrapper example

One of the most useful overrides you can re-implement is the ConfigureConventions override.

You will remember from previous chapters that Nancy looks for all its content in one place: underneath a folder called Content relative to the running assembly.

If you have the defaults in place, then this means that scripts will likely be in Contents/Scripts/ followed by the name of the JavaScript you want to use.

You can easily change this by overriding the ConfigureConventions method and adding your custom paths. For my demo application, I did the following:

Code Listing 59

using System.Text; using demodata; using demodata.entities; using Nancy; using Nancy.Authentication.Forms; using Nancy.Bootstrapper; using Nancy.Conventions; using Nancy.Session; using Nancy.TinyIoc; namespace nancybook { public class CustomBootstrapper : DefaultNancyBootstrapper { protected override void ConfigureConventions(NancyConventions nancyConventions) { Conventions.StaticContentsConventions .Add(StaticContentConventionBuilder.AddDirectory("/scripts", @"Scripts")); Conventions.StaticContentsConventions .Add(StaticContentConventionBuilder.AddDirectory("/fonts", @"fonts")); Conventions.StaticContentsConventions .Add(StaticContentConventionBuilder.AddDirectory("/images", @"Images")); Conventions.StaticContentsConventions .Add(StaticContentConventionBuilder.AddDirectory("/", @"Pages")); } } } |

I then created scripts, fonts, images and pages in my Solution Explorer, and ensured that NamespaceProvider was set to True for them, so they would be copied to the same location as my compiled assembly once run.

This allowed me to use the normal NuGet installation procedures for CSS, JavaScript, and other ASP.NET-related web packages, and meant that any files I included would be copied to my application build.

You'll notice that all requests to / are set to look in a folder called Pages; the one thing you cannot do here is point / to your application root; Nancy recognises the security risk this poses and won't allow it to happen.

What this means in practice is that I can put normal, static HTML files in the pages folder, and then add /blah.html to make a request. Nancy will return a static HTML file called blah.html from that folder. This allows you to mix traditional classic HTML, Scripts, and CSS files that are served without being processed by Nancy, alongside Nancy's powerful routing engine and API/URL features. I'm employing the very method for the work I've been doing on the Lidnug website, where I'm delivering the user interface directly at high speed using JavaScript for interaction on the client. The JavaScript in this user interface then calls on different endpoints provided by Nancy's web framework to service the AJAX requests made from the client.

If you've used NodeJS at all, you'll recognize almost immediately that this is exactly the same way that it works when used with frameworks such as Express.

The clever part here is not the way it works, but the fact that you can take your application and deploy it freely to a server with or without a web server already in place, which makes it perfect for creating lightweight microservice architecture-based deployments.

Summary

In this chapter, you learned how Nancy's bootstrapper works, and how its built-in IoC container can simplify how you design your Nancy applications.

You also learned how to use the bootstrapper to create static conventions that work on all platforms, allowing you to serve your site up even without using a web server.

In the next chapter, we'll take a look at Nancy's request pipelines, which are usually configured in the bootstrapper.

- 1800+ high-performance UI components.

- Includes popular controls such as Grid, Chart, Scheduler, and more.

- 24x5 unlimited support by developers.