CHAPTER 1

Introduction to MSIX

“Modernize: to make (something) modern and more suited to present styles or needs.”

In the tech world, we see amazing new software products being launched every day: beautiful websites, rich mobile applications, holographic experiences, and many more. We see these applications being advertised on tech websites, social networks, and sometimes even on television. These products are installed on every smartphone or PC; they are developed with an agile approach and constantly updated; they leverage the latest and greatest development technologies available on the market.

However, there’s an even larger number of applications that are critical for banks, big enterprises, hospitals, and schools. These applications are big and complex, and they were written many years ago. They perform important tasks, so they can’t be easily replaced with a new and modern product.

The world we’re living in is becoming a challenge for these kinds of applications. Users are more tech-savvy today, and they expect more from an application. Security challenges are increasing day by day, and as the number of users grows, applications need to scale accordingly.

Many companies, including Microsoft, have launched great frameworks and tools for building modern native desktop applications, such as Universal Windows Platform, Electron, and Progressive Web Apps. However, in many cases, the developer must start from scratch to leverage them. Unfortunately, due to their complexity, it’s not always feasible to entirely rewrite these applications to accommodate the new requirements

The same challenge applies to application packaging and deployment. Windows 10 introduced a more powerful deployment model, but in the beginning, it was applicable only to the new generation of modern applications, based on platforms like the Microsoft Store or the Microsoft Store for Business.

This is where app modernization comes in. Why do we have to completely rewrite an application? Why not just use the existing product and focus on the components that need to be enhanced? Or why can’t we use the same deployment techniques of modern applications for classic desktop applications?

In this book, we’re going to understand better how Windows 10 can help us take our Windows applications to the next level without having to rewrite them. The starting point will be MSIX, a new packaging format that Microsoft introduced in Windows 10 1809 (which was launched in October 2018). It aims to replace all the existing packaging and deployment technologies, like MSI and App-V.

The Universal Windows Platform

With the release of Windows 8, Microsoft introduced a new kind of application: Windows Store apps, based on a new framework called Windows Runtime. Unlike the .NET Framework, the Windows Runtime is a native layer of APIs that are exposed directly by the operating system to applications that want to consume them. With the goal to make the platform viable for every developer, the Windows Runtime introduced language projections, which are layers added on top of the runtime to allow developers to interact with it using well-known and familiar languages, like C# and C++.

The Windows Runtime libraries (called Windows Runtime components) are described using special metadata files that make it possible for developers to access the APIs using the specific syntax of the language they’re using. This way, projections can also respect the language conventions and types, like uppercase if you use C#, or camel case if you use JavaScript. Additionally, Windows Runtime components can be used across multiple languages; for example, a Windows Runtime component written in C++ can be used by an application developed in C# and XAML.

With the release of Windows 10, Microsoft introduced the Universal Windows Platform, which can be considered the successor of the Windows Runtime, since it’s built on top of the same technology. The unique point of the Universal Windows Platform is that it offers a common set of APIs across every platform; whether the app is running on a desktop, an Xbox One, or a HoloLens, you’re able to use the same APIs to reach the same goals. This was a major step forward compared to the original Windows Runtime, which didn’t provide this kind of cross-device support. You were able to share code and UI between a PC project and a mobile project, but, in the end, developers needed a way to create, maintain, and deploy two different solutions.

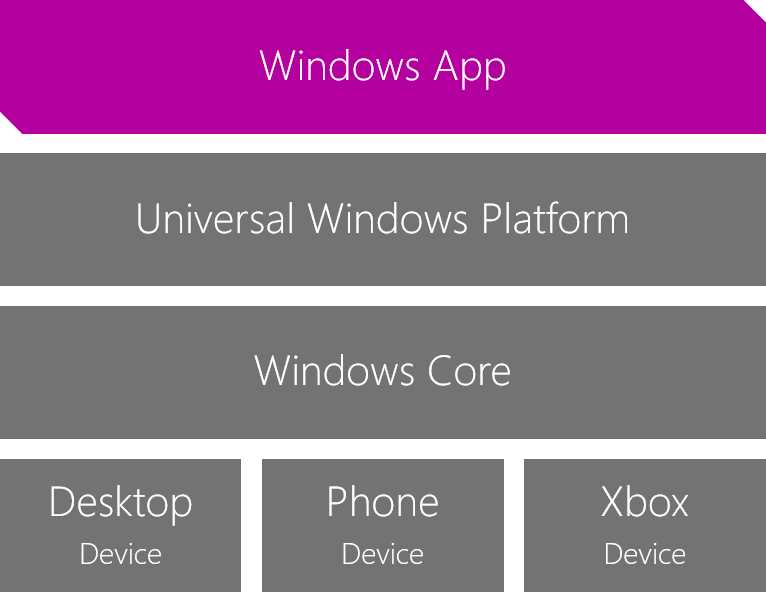

Figure 1 shows where the Universal Windows Platforms fits in the overall Windows 10 architecture: every device, despite having a different shell, shares the same kernel, which is the Windows Core. On top of the core, the Universal Windows Platform provides a consistent set of APIs to access to all the functionalities that are exposed by the core, like network access, storage, and sensors. A Windows app runs on top of the Universal Windows Platform, and it’s a single binary package.

Figure 1: The Windows 10 ecosystem for developers

Another important shift in the Universal Windows Platform is that, when it comes to the C# and XAML projection, it doesn’t leverage the standard .NET Framework, but a new, modern framework called .NET Core.

.NET Core can be considered the successor of .NET Framework, and was built from scratch according to the new Microsoft principles: open source and cross platform. The adoption of .NET Core and .NET Standard, the new formal specification of .NET APIs, makes it easier to reuse the parts of the code base that don’t have a specific dependency on the platform with other projects, no matter if it’s a web application or a traditional desktop application. However, it’s important to underline that this doesn’t mean that Universal Windows Platform apps can also run on other platforms like Android and iOS. The Universal Windows Platform, in fact, is built on top of .NET Core, and it leverages its common base, but it adds a set of APIs and features that are Windows-specific.

.NET Core, in the first releases, was focused on building cloud and web workloads. Things are changing with the release of .NET Core 3.0, which allows desktop frameworks (WPF and Windows Forms) to run on top of it instead of using the full .NET Framework.

Modern applications and desktop applications

With the release of the Windows Runtime in Windows 8 first, and the Universal Windows Platform in Windows 10 later, the Windows team has added first-class support to all the new features that you can expect from a modern application, like:

- Native support for new interaction paradigms, like touch, inking, and voice.

- New security features, like authentication with biometric parameters (fingerprint, face recognition, etc.).

- Fluid user experience and animations.

- Integration with all the new Windows 10 features, like Cortana, Timeline, live tiles, and cross-device communication.

- A better deployment system.

The Universal Windows Platform is also frequently updated. Windows 10 introduced the concept of Windows as a service. The operating system is constantly updated with new features, which are deployed twice per year with the release of a feature update. Every update also comes with a new version of the Windows SDK, which brings new APIs, improvements, and support to interact with the new features.

Universal Windows Platform applications have a minimum footprint and a better security model, thanks to the usage of containers. They can be easily installed and kept up to date using distribution platforms like the Microsoft Store or the Microsoft Store for Business. In addition to providing access to a wider set of APIs, the Universal Windows Platform introduced a very different application model compared to the existing one leveraged by Win32 applications, since it was built with security and privacy in mind. As such, Universal Windows Platform applications run inside a sandbox, they don’t have access to the registry, and they can freely read and write data only in a specific local folder. Any operation that is potentially dangerous requires the declaration of a capability and the consent of the user. Some examples are accessing the files in the Pictures library, using the microphone or the webcam, and retrieving the location of the user. Everything is controlled by a manifest file, which is an XML file that describes the identity of the application: its unique identifier, its capabilities, its visual aspect, and its integration with the Windows 10 extension points. These applications are deployed using new platforms like the Microsoft Store or the Microsoft Store for Business, which solve many of the distribution challenges, like auto-updates and license tracking.

On the other hand, classic desktop platforms like Windows Forms and WPF are considered stable and mature and are often still the first choice when it comes to developing a traditional enterprise application optimized for mouse and keyboard. Additionally, they can leverage the whole Windows API surface, so they are limited only by the running context (standard user vs. administrator). They can read and write from the registry, read and write in any folder, and interact with external peripherals. This approach is very powerful, but it also has some downsides. Applications can perform malicious tasks, like accessing any file on your computer, or interacting with any hardware device connected to the computer. When it comes to distribution, enterprises need flexibility, and they need to be able deploy applications in multiple ways: from a website, using System Center Configuration Manager or Intune, etc. As such, IT pros leverage technologies like MSI, ClickOnce, or App-V to satisfy all the requirements of the company.

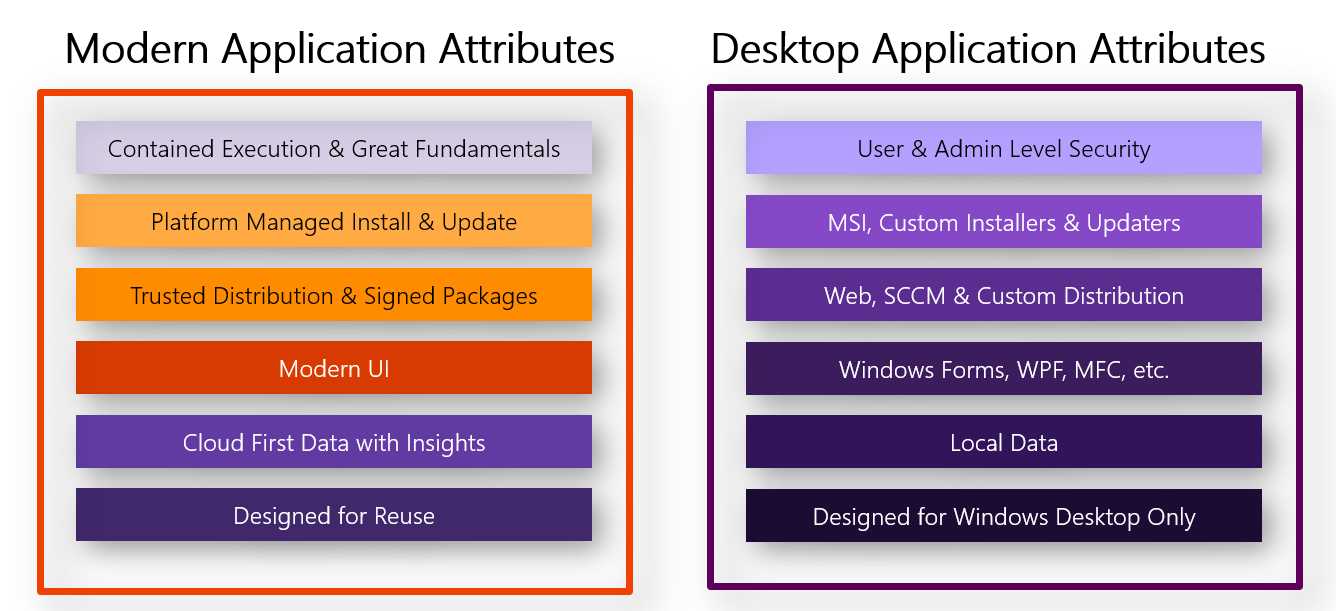

Figure 2: The main features of the two development ecosystems for Windows

In the beginning, the two worlds we have just described were in conflict—either you developed your applications for the modern desktop by leveraging the Universal Windows Platform model, or you kept using the Win32 technologies like WPF and Windows Forms. These technologies are still perfectly reliable and supported, but they don’t allow you to take advantage of all the benefits of a modern ecosystem, and they can’t be deployed using the new Windows 10 model.

The release of the Windows 10 Anniversary Update has started to change this approach by introducing a technology called Desktop Bridge. Thanks to it, traditional desktop applications had the chance to leverage the same deployment model of the Universal Windows Platform.

Desktop Bridge allows us to describe Win32 applications with a manifest file, too, which means that they get an identity. For developers, this feature allows the usage of APIs of the Universal Windows Platform. In the following years, the story has evolved with many new tools and technologies for app modernization: MSIX, XAML Islands, .NET Core 3.0, etc. For IT pros, this means that classic desktop applications can take advantage of all the benefits of the new deployment model introduced in Windows 10.

The goal is to remove the barrier between traditional desktop development and modern development. No matter which development technology you’re using, you have the chance to leverage all the benefits of a modern ecosystem without rewriting your application from scratch by integrating the existing code with the features you’re interested in.

MSIX, the new packaging format introduced in Windows 10, version 1809, is the starting point of this modernization journey. Let’s learn a bit more about it.

A new approach to packaging

Windows 8 was the first version of Windows that introduced a new packaging technology for applications, called AppX. At the time of the release, however, it wasn’t very flexible. It supported only Windows Store applications, packages could be deployed only from the Store, and sideloading was enabled only on devices unlocked for development purposes or with a special license.

Windows 10, release after release, has continued to enhance this packaging format by opening it up more and more to be suitable for any kind of app distribution, regardless of the technology (UWP, WPF, Windows Forms, Java, etc.) and the deployment approach (Store, enterprise management tools, sideloading, etc.).

Here is the timeline of the key changes:

- Windows 10: The first release of Windows 10 removed the requirement to have a special license to sideload enterprise applications packaged using AppX. It was enough to turn on the Sideload apps option in the Windows settings.

- Windows 10, version 1511: The first update for Windows 10, called the November Update, has turned on by default the option to allow package sideloading. Every user, without changing the Windows configuration, was able to install packages coming from a trusted source, like your workplace.

- Windows 10, version 1607: The Anniversary Update introduced the Desktop Bridge. Thanks to this technology, the AppX packaging format has been extended to the Win32 ecosystem. From now on, applications built with WPF, Windows Forms, Java, etc., can be packaged using AppX and take advantage of the new deployment format and the opportunity to be published on the Microsoft Store.

- Windows 10, version 1809: This version of Windows introduced MSIX, the evolution of the AppX format. Built on the same fundamentals, it further opened the ecosystem to better support enterprise scenarios and helped IT departments move to a better deployment approach.

Another big change compared to AppX is that MSIX is aligned to the new Microsoft philosophy and, as such, it’s an open-source and cross-platform project. It offers SDKs to work with this packaging format for all the major platforms, either mobile (Android and iOS) or desktop (MacOS, Linux). Of course, this doesn’t mean that MSIX packages can be deployed out of the box on every platform. The owner of the other operating systems, in fact, would need to implement MSIX support first. However, thanks to these SDKs, we aren’t limited to creating or unpacking MSIX packages only on Windows.

The benefits of MSIX for developers

Until now, the installation and deployment of Windows applications never followed a specific standard. The developer has always been in charge of identifying the best experience for customers, often by leveraging third-party tools.

As such, developers are required to take care of many tasks that go beyond the development of the application, like:

- Identifying the right installer technology from among the ones available on the market (MSI, ClickOnce, InstallShield, etc.).

- Handleing the installation and uninstallation process to make sure that everything is deployed in the right place and that, when the user doesn’t need the app anymore, they can uninstall it, leaving the system in a reliable state.

- Implementing a custom solution to handle the auto-update of the application. Delivering a bad update experience can lead users to stick with the version they have downloaded and never update it, which prevents them from accessing new features or critical security updates.

- Providing a platform to distribute and sell their application, like a website integrated with a monetization system.

This approach has many downsides for the final users, especially since the rise of the mobile market. Users are now accustomed to having a single point of access to download applications (typically a store), which provides a seamless experience. You press a button, and the application is installed. You press another button, and the application is removed. Everything is automatically kept up to date, without any user intervention. The purchase process is also safer, because you aren’t sharing your credit card data directly with the developer, but with the owner of the platform, which is typically a trusted company (such as Apple or Google).

For most desktop applications, this isn’t the case. Applications are distributed from a website, which the user must find with a search engine and browser. Sometimes, this approach leads to the download of malicious applications that use popular brands and names to spread malware and viruses. Additionally, based on the installer technology chosen by the developer, installing, uninstalling, or updating an application can be a challenging task, especially for users who aren’t really tech-savvy.

Windows 10 introduced a different approach to help users handle Windows applications in an easier way, by providing an experience closer to the one people find on their phones. Thanks to a central point of distribution, the Microsoft Store, users don’t have to browse the web to find the application they need. Because of the trusted distribution environment, users can be sure they’re downloading the right application, and not a malicious clone. The Microsoft Store can also automatically take care of many tasks that, in the past, needed to be implemented by the developer, like automatic updates or monetization.

In the first releases of Windows 10, this new approach was reserved to Universal Windows Platform applications, since AppX supported only this modern framework. With the Windows 10 Anniversary Update, Microsoft opened it up to classic desktop applications, after introducing the Desktop Bridge. This new technology allowed developers to release Win32 applications packaged as AppX on the Microsoft Store, or to deploy them manually in a managed environment, like an enterprise.

In the end, the new packaging format isn’t just a way to deploy applications in a better way, but also to help you move your applications forward. Packaged applications, in fact, get an application identity, which means that they can be univocally identified by Windows 10. This feature allows an application to leverage the APIs provided by the Universal Windows Platform and start using features like toast notifications, live tiles, and Windows Hello. In Chapter 6, we’re going to see how, after we have packaged our classic desktop application using MSIX, we can start to add new features offered by the Windows 10 ecosystem.

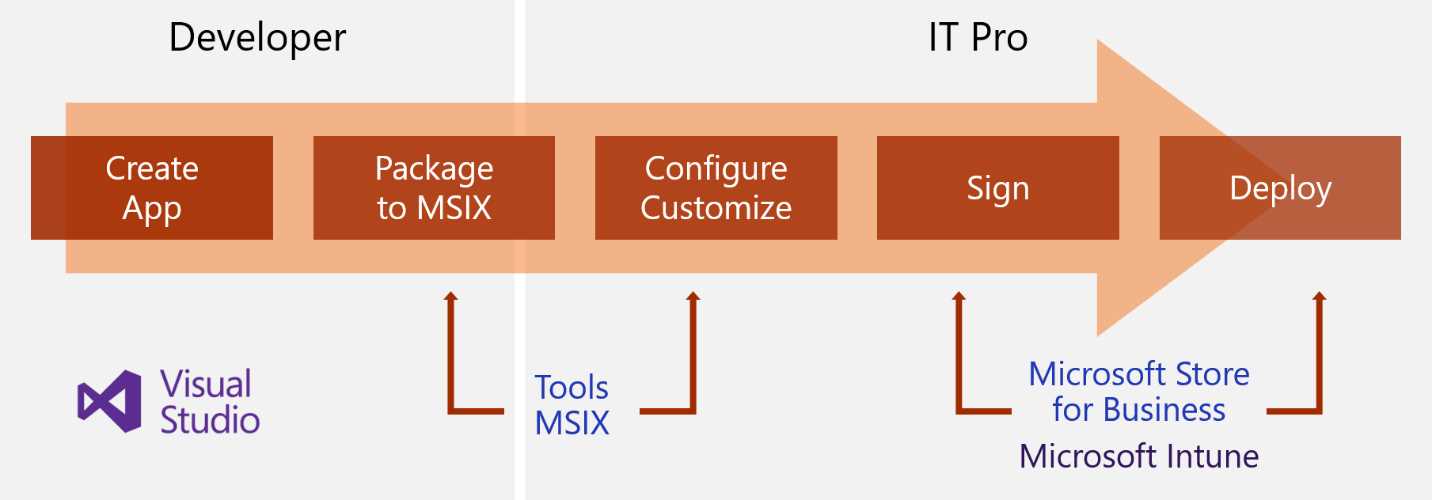

The benefits of MSIX for IT pros

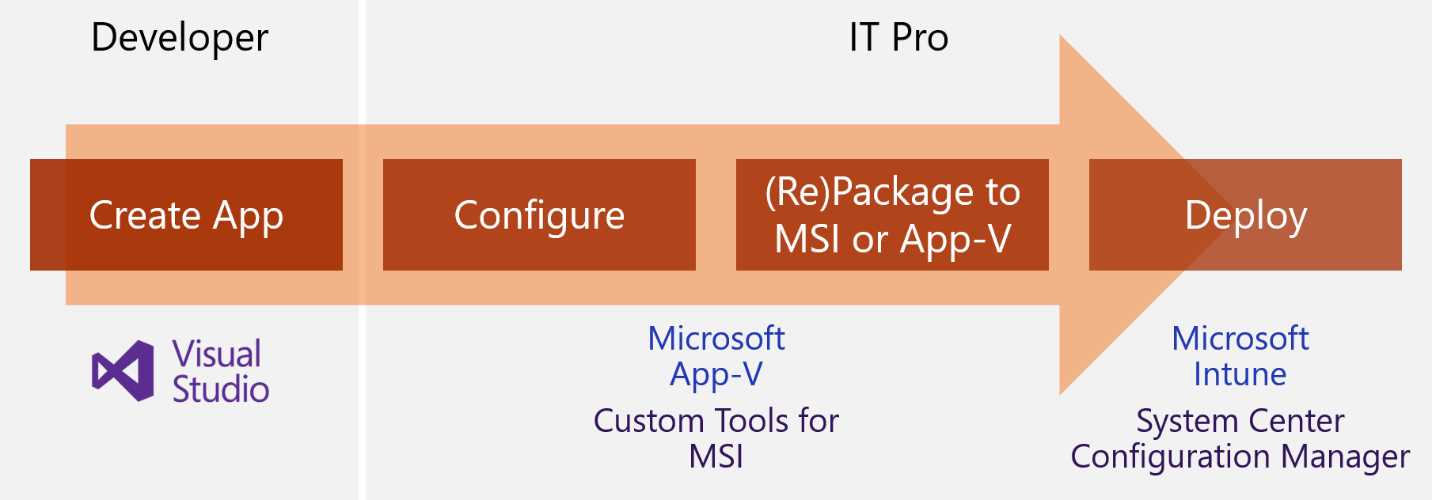

Deployment has always been a pain point not only for developers, but also for IT pros in charge of maintaining the application’s catalog of enterprises with thousands of devices. When it comes to deploying an application within a company, in fact, IT pros can rarely afford to deploy it as is. In most cases, they need to customize the installer to accommodate the requirements of the company, such as specific configurations or branding. To satisfy this need in the past, Microsoft created technologies like App-V and Custom Tools for MSI, which allow you to take the installer provided by a developer and customize the deployment process.

Figure 3: The typical application lifecycle today in the IT Pro pro world, as described by John Vintzel in his session “MSIX: Inside and out” at Ignite 2018

This approach, however, has often created a packaging paralysis within companies. Since applications, customizations, and the operating system are coupled bound together, every time a new update is released, the IT department is required to repackage the application from scratch. This increases costs and time and slows down the company’s ability to release new updates to the employees.

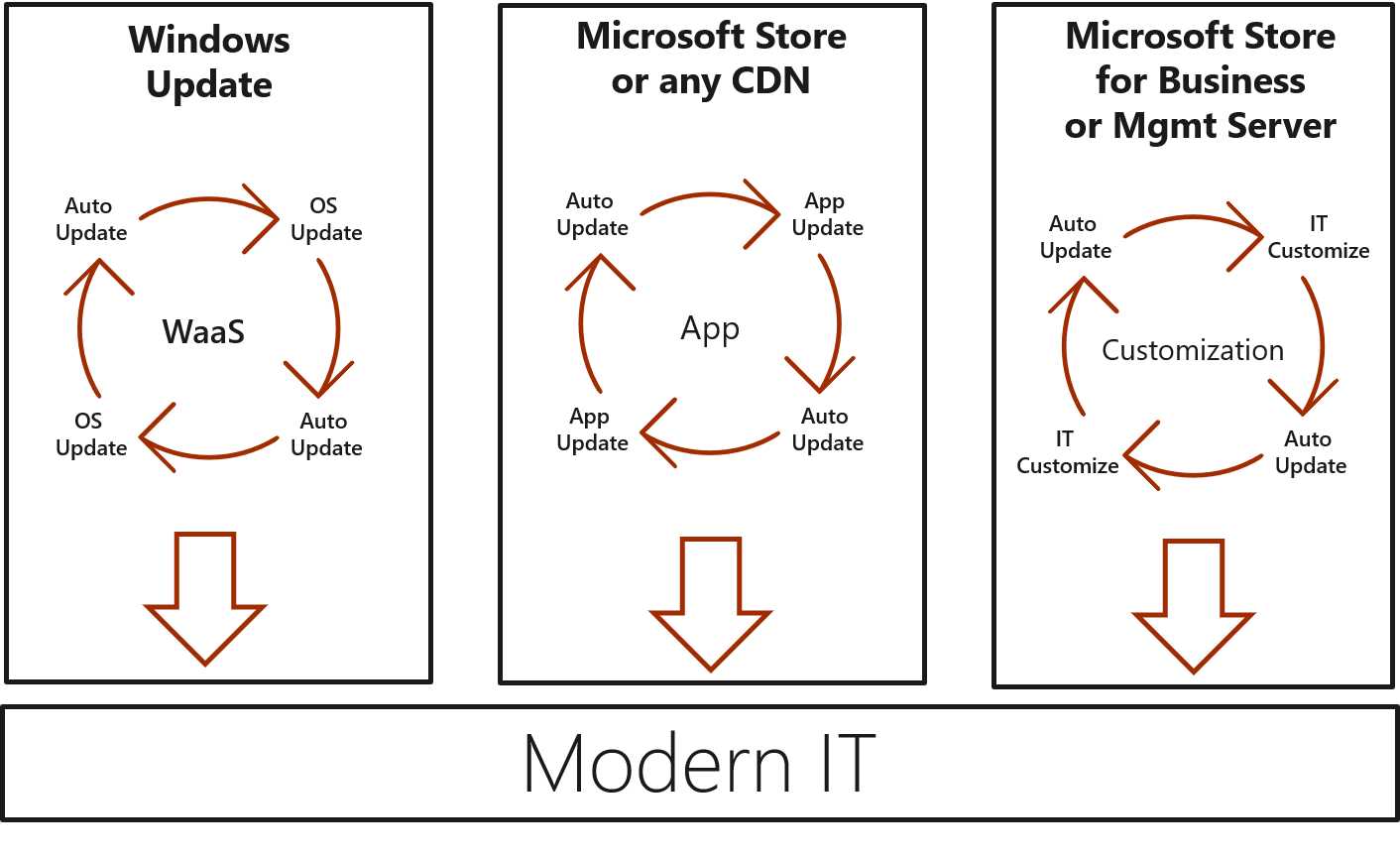

The MSIX packaging format, instead, helps to decouple separate the various aspects of the application deployment, allowing IT pros to independently deploy Windows updates, application updates, or customizations. This way, when a developer releases a new version of the application, or Microsoft publishes a new Windows update, it can be directly deployed without any repackaging process in between.

Figure 4: In the modern IT, all the components of the infrastructure should be able to update independently, as described by John Vintzel in his session “MSIX: Inside and out” at Ignite 2018

MSIX is enterprise-friendly. In addition to supporting new distribution platforms, like the Microsoft Store (including the private versions, the Microsoft Store for Business, and the Microsoft Store for Education), it works just fine with all the existing enterprise management tools, like System Center Configuration Manager and Microsoft Intune. It also supports manual distribution by publishing the package on a website or on a network share.

Figure 5: The modern application lifecycle in the IT Pro world, as described by John Vintzel in his session “MSIX: Inside and out” at Ignite 2018

The features of MSIX deployment

The goal of the MSIX packaging format is to become the deployment solution moving forward by helping to solve all the challenges that developers and IT pros have faced in the past with other distribution formats.

Let’s look at the main benefits of adopting MSIX compared to other installer technologies.

Simple packaging

MSIX is a very simple packaging format. It’s basically a compressed file that contains the application, plus a set of files that are required by Windows to handle the deployment. The most important file is the manifest, which is an XML file that describes the application and defines its identity. Thanks to the manifest, Windows can handle the deployment and understand if the application is already installed, or if the current package is an update.

Being declarative, it’s very simple to integrate with Windows 10, since all the extension points (like supporting file-type association or startup tasks) are handled with a simple entry in the manifest. We’re going to learn more about Windows 10 integration in Chapter 5.

Secure and reliable

MSIX provides a more reliable deployment approach since it’s handled directly by Windows. As such, the operating system can keep track of all the files and registry keys that are created during the deployment phase and at runtime and perform a clean uninstall when the application is removed. This helps Windows be reliable and stable over time, since it reduces the number of unused registry keys and files that are often left in the system by traditional uninstallers.

MSIX is also safer, because packages must come from the Microsoft Store or from a trusted source, which means that they must be signed with a digital certificate that is trusted by the machine. In the case of an enterprise, for example, they can be signed with an internal certificate generated by the company. If a package isn’t signed, or isn’t signed with a trusted certificate, there’s no way to deploy it on a machine for a regular user.

MSIX also has built-in anti-tamper technology. If the files that compose the application are changed by a third-party application or by manual intervention, Windows will prevent the execution. If the application has been downloaded from the Microsoft Store, Windows will repair it automatically. If it’s coming from a different source, it will be up to the user or the IT department to reinstall it.

Flexible distribution

One of the original blockers in the adoption of the AppX packaging format by enterprises wereas the limited distribution opportunities. Only the Microsoft Store was supporting the distribution of these new packages. This approach works great for consumers, but enterprises need more control over the deployment.

Over time, the deployment opportunities for AppX have steady increased, and today, MSIX can be deployed with any technology currently used to distribute traditional installers, like System Center Configuration Manager, Microsoft Intune, or simply an internal network share or website. Additionally, thanks to a technology included in Windows 10 called App Installer, you can implement some of the benefits of store distribution, like auto updates, even with a more traditional deployment approach. We’re going to learn more about this opportunity in Chapter 7.

OS managed and optimized

Windows oversees every step of the deployment, from the installation to the removal to the update process. As such, it’s able to automatically optimize many of these processes, without any special requirement for the developer or the IT pro:

- Incremental updates: Developers don’t need to handle the optimization of the update process. They can just create a new package with the whole content of the application, no matter what the size is. Windows, before downloading the update from any source (the Microsoft Store, Intune, a web location, etc.), will check the hash table of the files included in the original package. It will match them with the ones of the updated package. Windows will download only the files that have changed, helping to save bandwidth and disk space.

- Single instance of storage files: If you deploy multiple packages with the same content (for example, a framework or library), Windows will maintain a single copy on the disk and, with a linking mechanism, will provide the files to the application that needs them. This process is completely transparent to the applications, which will behave as if the files are physically included inside the deployment folder. However, files will be stored just once, helping to save disk space.

- Resource packages: MSIX packages can be split in multiple subpackages that contain resources related to a specific configuration, like images or translations. Windows will download only the relevant packages for the current configuration of the user.

The architecture of an MSIX package

An MSIX package is a simple file container for an application. Inside it, you will find all the files that make up your application, plus a set of special files and folders:

- AppManifest.xml: The manifest file, which describes the application. We’re going to see more details about the manifest file later in this section.

- VFS: A special folder used to abstract the file system and provide virtualized access to system folders. We’ll see more details later in this chapter.

- Assets: The folder that contains the default image assets leveraged by Windows 10. These are the icons used for the Start menu entry, the tile, and the icon in the taskbar.

- A set of files with the .dat extension: These files map the various registry hives that are part of the system registry, and they include the keys that must be created during the deployment phase.

When you deploy an MSIX package, its content is automatically uncompressed in a special, system-protected folder: C:\Program Files\WindowsApps. The name of the folder where the application will be stored depends on the Package Full Name, which is a unique identifier. It’s a combination of the name of the publisher, the name of the app, the version number, the target CPU architecture, and the hash of the publisher.

For example, this is the path of the MSIX Packaging Tool, the tool by Microsoft to package applications as MSIX, which we’re going to explore in Chapter 2.

C:\Program Files\WindowsApps\Microsoft.MsixPackagingTool_1.2019.402.0_x64__8wekyb3d8bbwe

The folder name is composed of the following elements:

- Microsoft: The publisher’s name.

- MsixPackagingTool: The application’s name.

- 1.2019.402.0: The version number.

- x64: The CPU architecture for which the application is compiled.

- 8wekyb3d8bbwe: The publisher’s hash.

The most important file of the package is the manifest, named AppxManifest.xml. It’s an XML file defining many important aspects of the application, like its identity, the leveraged capabilities, and the extensions. Visual Studio includes a visual editor for the manifest, which makes it easier to edit it. However, since we don’t always have the opportunity to access the source code of the project, it’s important to understand the XML structure.

Let’s see how the manifest looks.:

Code Listing 1

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?> <Package xmlns="http://schemas.microsoft.com/appx/manifest/foundation/windows10" xmlns:uap="http://schemas.microsoft.com/appx/manifest/uap/windows10" xmlns:uap2="http://schemas.microsoft.com/appx/manifest/uap/windows10/2" xmlns:uap3="http://schemas.microsoft.com/appx/manifest/uap/windows10/3" xmlns:rescap="http://schemas.microsoft.com/appx/manifest/foundation/windows10/restrictedcapabilities" > <Identity Name="NotepadPlusPlus" Publisher="CN=mpagani" Version="1.0.0.0" ProcessorArchitecture="x64" /> <Properties> <DisplayName>Notepad++</DisplayName> <PublisherDisplayName>Matteo Pagani</PublisherDisplayName> <Description>Reserved</Description> <Logo>Assets\StoreLogo.png</Logo> </Properties> <Resources> <Resource Language="en-us" /> </Resources> <Dependencies> <TargetDeviceFamily Name="Windows.Desktop" MinVersion="10.0.17763.0" MaxVersionTested="10.0.18362.0" /> </Dependencies> <Capabilities> <rescap:Capability Name="runFullTrust" /> </Capabilities> <Applications> <Application Id="Notepad" Executable="Notepad++\notepad++.exe" EntryPoint="Windows.FullTrustApplication"> <uap:VisualElements BackgroundColor="transparent" DisplayName="Notepad++" Square150x150Logo="Assets\Square150x150Logo.png" Square44x44Logo="Assets\Square44x44Logo.png" Description="Notepad++"> <uap:DefaultTile Wide310x150Logo="Assets\Wide310x150Logo.png" Square310x310Logo="Assets\Square310x310Logo.png" Square71x71Logo="Assets\Square71x71Logo.png" /> </uap:VisualElements> <Extensions> <uap:Extension Category="windows.fileTypeAssociation"> <uap3:FileTypeAssociation Name="notepad"> <uap:SupportedFileTypes> <uap:FileType>.txt</uap:FileType> <uap:FileType>.rtf</uap:FileType> </uap:SupportedFileTypes> </uap3:FileTypeAssociation> </uap:Extension> </Extensions> </Application> </Applications> </Package> |

Let’s analyze the key elements.

The identity

The identity of the application is defined by the Identity tag, and it’s composed of:

- A name.

- The identifier of the publisher of the application. It must match the subject of the digital certificate that will be used to sign the package.

- The version number.

The identity is used by Windows to handle the lifecycle of the package. For example, by matching the name and the publisher, it’s able to understand if whether a specific application is already installed in the system. Or, by using the version number, it’s able to understand if Windows needs to perform an upgrade or a clean installation.

The Properties section contains some other important information that defines the identity of the application, like the name and the publisher that will be displayed to the user. This information is particularly important if you’re going to publish the application on the Microsoft Store. The application’s name, in fact, must match the name you reserved on the Microsoft Store. The publisher’s name, instead, must be the same one you chose when you opened an account on the Microsoft Partner Center, the web portal used to submit applications on the Microsoft Store.

The capabilities

Capabilities are used by Windows to understand which features are leveraged by the application, and they act like a security gateway for the most sensitive ones. If an application doesn’t declare a specific capability, all the APIs that try to invoke the related feature will return an error. Some examples of capabilities are Internet internet access, camera access, and location access.

This capability model mostly applies to Universal Windows Platform applications and components. Classic desktop applications, since they are built with a wide range of technologies released before the advent of Windows 10, can’t leverage such a tailored capability system, and they will simply be ignored.

However, there’s a key capability that must be declared by every Win32 application, called runFullTrust, which allows them to keep leveraging the classic Windows model (no sandbox, direct access to the file system and the registry, etc.). It’s a restricted capability. From an enterprise point of view, it doesn’t require any special attention. The difference comes if you want to publish the application on the Store. In this case, you’ll be asked the reason you need to use such a restricted capability. You can find more details in Chapter 7.

The application

The Application node defines the main features of the application itself. The most relevant attributes are Executable and EntryPoint, which define the main process to invoke when the user launches the application.

These elements of the manifest make another difference between a Universal Windows Platform application and a classic desktop application:

- In a Universal Windows Platform application, the EntryPoint points to the main class that handles the activation of the application. Typically, it’s called App.

- In a classic desktop application, the EntryPoint attribute is set to the fixed keyword Windows.FullTrustApplication, while the Executable attribute points to the main executable.

The Application entry also has different sub-nodes for handling the visual elements of the application. They include a reference to the various assets used to display the application’s entry in the Start menu, in the taskbar, or as a tile in the Start screen.

Extensions

The Extensions section is optional, and it will be included only for applications that integrate with Windows 10. Some examples of integration are file type association, supporting launch at startup, and defining a global alias. The most relevant extensions will be detailed in Chapter 5.

In Code Listing 1, you can see, for example, the required entry to set up file type association. Thanks to this entry, Windows will offer to users the opportunity to automatically open the application automatically when they double-click on a file with the extension .txt or .rtf.

The container

Unlike Universal Windows Platform applications, which run inside a sandbox, classic desktop applications packaged as MSIX still retain full access to the operating system. However, to make the application safer and more reliable, MSIX provides a lightweight container that helps to virtualize some of the critical aspects of an application.

Let’s see them in detail.

The virtual file system

An MSIX package contains a special folder called VFS, which can map most of the system folders that you find in Windows, like C:\Windows, C:\Windows\System32, C:\Program Files. When a packaged application needs to load a file from one of these folders, Windows will look first inside the VFS folder of the package, and if it doesn’t find it, it will forward the request to the real system folder.

Here is a list of the most relevant supported folders, taken from the official documentation:

Table 1: System folders supported by the virtual file system

System location | Redirected location in the VFS folder |

|---|---|

C:\Windows\System32 | SystemX86 |

C:\Windows\SysWOW64 | SystemX64 |

C:\Program Files (x86) | ProgramFilesX86 |

C:\Program Files | ProgramFilesX64 |

C:\Program Files (x86)\Common Files | ProgramFilesCommonX86 |

C:\Program Files\Common Files | ProgramFilesCommonX64 |

C:\Windows | Windows |

C:\ProgramData | Common AppData |

This feature was introduced to help package application-handling dependencies, like frameworks and libraries, in an easier way. Thanks to this approach, you can mitigate the problem known as “DLL hell,” which happens when you have multiple applications on your system that depend on the same framework or runtime. At some point, you may have to install another application that has a dependency on a newer version of the same framework. Since this framework can be installed only at a system level, you are forced to overwrite the existing version, which can lead the other applications to break or not behave well.

Thanks to the virtual file system, you can embed inside every package the exact version of the framework required by the application. Since each package lives in its own folder, it won’t try to replace other versions of the same framework you may have on your machine. The existence of the virtual file system is completely transparent for the application: it will continue to think that the libraries are part of the operating system. As such, no code changes are required to support this feature.

Additionally, thanks to the file-linking optimization supported by MSIX packages, even if multiple applications should include the same version of a framework, disk space will be optimized, because the files will be physically saved just once, and then linked in each package that requires it.

This feature is also helpful for providing a better deployment experience for the user. Thanks to this approach, users can install an application and use it right away, without having to manually download any required dependency. If you’re interested in publishing your packaged application on the Microsoft Store, this is a strict requirement. An application that doesn’t automatically satisfy all the dependencies and requires the user to manually download them from a website or another source, is in violation of the Microsoft Store policies.

Registry virtualization

Each packaged application has access to a virtualized version of the user hive in the system registry. This means that every time the application tries to create or update a registry key under the HKEY_CURRENT_USER hive, it will be stored in its private hive and not in the system registry. Read operations, instead, will be performed against a merged version of the registry. If the hive you’re trying to read from doesn’t exist in the local one, Windows will redirect the operation to the system one.

Keys that must be created in the system-wide hives, like HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE, are stored, instead, in special files with .dat extensions, which are placed in the root of the packages. These keys will also be created in the virtual registry during the package deployment; the application will be able to read them, but they won’t be visible in the real system registry. These files are typically created during the packaging process, using the MSIX Packaging Tool we’re going to see in Chapter 2.

This virtualization helps to deliver a clean uninstallation process. When the application is removed, Windows will simply remove all the binary files that are used to store the registry keys, making sure that no orphan keys are left in the real system registry.

File system virtualization

Windows comes with a special folder called AppData, which lives under the user profile (C:\Users\<username>\AppData). This is the suggested location where applications should keep all the local application data: logs, databases, and, generally speaking, every file that has a tight relationship with your application. As such, it should be removed when it’s uninstalled.

Like for the registry, Windows virtualizes this folder. Whenever your application tries to read or write files in the AppData folder, Windows will redirect the operation to the local storage of the application, which is a special folder visible only to it.

The local storage of each application is stored inside a folder with the following path:

C:\Users\<username>\AppData\Local\Packages\<Package Family Name>\LocalCache.

Using again the MSIX Packaging Tool as an example, this is the location where its AppData folder is redirected.

C:\Users\<username>\AppData\Local\Packages\Microsoft.MsixPackagingTool_8wekyb3d8bbwe\LocalCache

The folder name is composed of the following elements:

- Microsoft is the publisher’s name.

- MsixPackagingTool is the application’s name.

- 8wekyb3d8bbwe is the publisher’s hash.

The operation will be completely transparent for the application. Developers don’t have to change the code to support this virtualization.

Like for the registry, this feature helps to deliver a clean uninstall. When the application is removed, Windows will delete the folder that contains the local storage of the application, making sure that there are no temporary files left in the system.

The requirements

MSIX is a great way to package your existing applications, but before starting the packaging process, it’s important to know that you must satisfy a set of requirements. Some of them come from the technology being new and, as such, it still doesn’t support all the scenarios. Some others are a consequence of the lightweight container we have talked about, which is transparent for most of the scenarios, but might be a blocker in some edge cases. It’s important to highlight that not all the requirements listed here are complete blockers. Thanks to tools like the Package Support Framework, which will be described in detail in Chapter 4, you can overcome some of these limitations, even if you don’t have access to the source code.

Let’s see the most relevant ones.

.NET Framework version

If your application is built with the .NET Framework, you must target at minimum version 4.0. The reason is that MSIX doesn’t support including older versions of the .NET Framework inside the package and, as such, you must rely of on the version which ships with Windows 10, which is greater than 4.x.

Unless you have any special requirement, the suggested minimum version is .NET Framework 4.6.2.

Windows services and drivers

The MSIX packaging format doesn’t currently support the deployment of NT services or custom kernel drivers. This is a blocker if your goal is to publish the application on the Microsoft Store, since you are not allowed to ask to the user to manually download a component that needs to be installed separately.

There are no restrictions when it comes to enterprise deployments. You can safely deploy the application as MSIX and then, using another technology, deploy the required driver or service.

The suggested path to deploy drivers is to certify and publish them on Windows Update.

Elevated security privileges

Applications packaged as MSIX are installed per user, and they are always expected to run in user mode, since users who install the application might not be system administrators. This is a strict requirement when the application is published to the Microsoft Store. For enterprise deployments, however, you can request administrative credentials if needed, even if it’s not suggested.

Windows 10 version 1809 has added a new special capability that can be declared in the manifest file, to support elevation at startup. However, it’s a restricted capability, and third-party applications published on the Microsoft Store won’t be allowed to use it. You can use it, instead, for applications that are deployed in an enterprise environment.

The restricted capability is called allowElevation.

Code Listing 2

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?> <Package xmlns:rescap="http://schemas.microsoft.com/appx/manifest/foundation/windows10/restrictedcapabilities" IgnorableNamespaces="rescap"> . . . <f:Capabilities> <rescap:Capability Name="runFullTrust" /> <rescap:Capability Name="allowElevation" /> </f:Capabilities> . . .</f:Package> |

Sharing data using the registry or the AppData folder

We have learned that a Windows application packaged as MSIX uses a virtualized version of the registry and of the AppData folder, which are private and visible only to the application itself. Therefore, your application can’t use one of these two locations to share data with other applications. Since all the registry keys and all the files in the AppData folder are visible only to the application itself, other applications can’t access them.

Writing to the installation folder

As already mentioned, during deployment, MSIX packages are uncompressed in a special folder (C:\Program Files\WindowsApps), which is system-protected and read-only. As such, if the application tries to write or update a file stored in the installation folder (for example, a log file), the operation will fail because it doesn’t have enough rights to perform the task.

This limitation can be overcome by changing the code to write the files in another, more suitable, location (like the AppData folder), or by using the Package Support Framework. We’ll see the details on this in Chapter 4.

Access to the Current Working Directory

If writing files to the installation folder isn’t allowed, you can safely perform reading operations. However, many applications use the concept of the current working directory (CWD) to perform this task, in which the path is returned by the shortcut created during the installation process. It typically matches with the folder where the application has been installed.

Since the deployment of a MSIX package doesn’t generate a traditional shortcut, the Windows APIs used to retrieve the current working directory will return a different path: C:\Windows\System32 if the application is compiled for a 32-bit architecture; or C:\Windows\SysWOW64 if the application is compiled for a 64-bit architecture.

As such, if your application tries to read a file inside the package using the current working directory, the operation will fail because it will look for the file in the wrong folder.

As with writing to the installation folder blocker, this limitation can be overcome by changing the code or by leveraging the Package Support Framework.

Down-level support and MSIX Core

One of the challenges you encounter when you want to introduce a new packaging and deployment system is providing support to all the platforms used by your customers. MSIX was introduced in Windows 1809; however, many enterprises are still on previous versions of Windows 10, since they need more time before adopting a newer version. To address this scenario, Microsoft has added down-level support for MSIX with a series of Windows 10 updates. MSIX packages can now be deployed on Windows 10, versions 1803 and 1709. This feature is focused mainly on enterprises and, as such, the support covers deployment using sideloading, SSCM (Microsoft System Center Configuration Manager, formerly Systems Management Server), and Intune. To download, instead, MSIX-packaged applications from the Microsoft Store, you will still need at least Windows 10, version 1809.

What about Windows 7? The end of support is approaching soon (January 2020), but there are still many enterprises that haven’t yet fully migrated to Windows 10. For this scenario, Microsoft is working on a project called MSIX Core, which is open source and currently on preview in GitHub. It’s a tool that you can install on Windows 7 (or any other Windows version that doesn’t support MSIX) to enable support for the new packaging format.

After installing the tool, you’ll be able to double-click an MSIX file and trigger the installation of the application. All the included files will be copied over to your hard disk, all the files stored inside the virtual file system will be copied in the system folders, and a link to the application will be added to the Start menu. In the end, an entry will be included in the Add/Remove Programs panel to allow uninstallation.

MSIX Core isn’t able to bring many of the MSIX features, like the file/registry virtualization or the optimized update experience. All these features are deeply rooted inside the Windows 10 kernel, and they would require significant updates to Windows 7 itself. However, thanks to MSIX Core, you won’t have to maintain two different distribution systems based on the OS you’re targeting, you’ll be able to use MSIX regardless of the customer’s operating system.

- 1800+ high-performance UI components.

- Includes popular controls such as Grid, Chart, Scheduler, and more.

- 24x5 unlimited support by developers.