CHAPTER 4

Naive Bayes Classification

Introduction

Most machine learning classification techniques work strictly with numeric data. For these techniques, any non-numeric predictor values, such as male and female, must be converted to numeric values, such as -1 and +1. Naive Bayes is a classification technique that is an exception. It classifies and makes predictions with categorical data.

The "naive" (which means unsophisticated in ordinary usage) in naive Bayes means that all the predictor features are assumed to be independent. For example, suppose you want to predict a person's political inclination, conservative or liberal, based on the person's job (such as cook, doctor, etc.), sex (male or female), and income (low, medium, or high). Naive Bayes assumes job, sex, and income are all independent. This is obviously not true in many situations. In this example, job and income are almost certainly related. In spite of the crude independence assumption, naive Bayes classification is often very effective when working with categorical data.

The "Bayes" refers to Bayes’ theorem. Bayes’ theorem is a fairly simple equation characterized by a "given" condition to find values such as "the probability that a person is a doctor, given that they are a political conservative." The ideas behind Bayes’ theorem are very deep, conceptually and philosophically, but fortunately, applying the theorem when performing naive Bayes classification is relatively simple in principle (although the implementation details are a bit tricky).

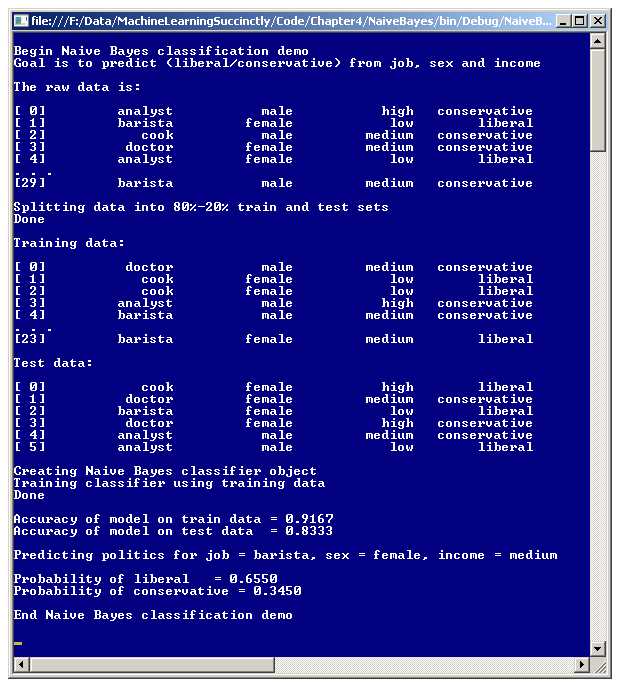

A good way to understand naive Bayes classification, and to see where this chapter is headed, is to examine the screenshot of a demo program, shown in Figure 4-a. The goal of the demo program is to predict the political inclination (conservative or liberal) of a person based on his or her job (analyst, barista, cook, or doctor), sex (male, female), and annual income (low, medium, high). Notice each feature is categorical, not numeric.

The demo program starts with 30 (artificially constructed) data items. The first two items are:

analyst male high conservative

barista female low liberal

The independent X predictor variables, job, sex, and income, are in the first three columns, and the dependent Y variable to predict, politics, is in the last column.

The demo splits the 30-item data set into an 80% (24 data items) training data set and a 20% (6 data items) test data set in such a way that the data items are randomly assigned to one of the two sets. The training data set is used to construct the naive Bayes predictive model, and the test data set is used to give an estimate of the model's accuracy when presented with new, previously unseen data.

Next, the demo uses the training data and naive Bayes mathematics to construct a predictive model. Behind the scenes, each feature-column is assumed to be independent.

After creating the model, the demo computes the model's accuracy on the training data set and on the test data set. The model correctly predicts 91.67% of the training items (22 out of 24) and 83.33% of the test items (5 out of 6).

Figure 4-a: Naive Bayes Classification Demo Program

Next, the demo program uses the model to predict the political inclination of a hypothetical person who has a job as a barista, is a female, and has a medium income. According to the model, the probability that the hypothetical person has a liberal inclination is 0.6550 and the probability that the person is a conservative is 0.3450; therefore, the unknown person is predicted to be a liberal.

The sections that follow will describe how naive Bayes classification works, and present and explain in detail the code for the demo program. Although there are existing systems and API sets that can perform naive Bayes classification, being able to write your own prediction system gives you total control of the many possible implementation options, avoids unforeseen legal issues, and can give you a good understanding of how other systems work so you can use them more effectively.

Understanding Naive Bayes

Suppose, as in the demo program, you want to predict the political inclination (conservative or liberal) of a person whose job is barista, sex is female, and income is medium. You would compute the probability that the person is a conservative, and the probability that the person is a liberal, and then predict the outcome with the higher probability.

Expressed mathematically, the problem is to find these two values:

P(conservative) = P(conservative | barista & female & medium)

P(liberal) = P(liberal | barista & female & medium)

The top equation is sometimes read as, "the probability that Y is conservative, given that X is barista and female and medium." Similarly, the bottom equation is, "the probability that Y is liberal, given that X is barista and female and medium."

To compute these probabilities, quantities that are sometimes called partials are needed. The partial (denoted PP) for the first dependent variable is:

PP(conservative) =

P(barista | conservative) * P(female | conservative) * P(medium | conservative) * P(conservative)

Similarly, the partial for the second dependent variable is:

PP(liberal) =

P(barista | liberal) * P(female | liberal) * P(medium | liberal) * P(liberal)

If these two partials can somehow be computed, then the two probabilities needed to make a prediction are:

P(conservative) = PP(conservative) / (PP(conservative) + PP(liberal))

P(liberal) = PP(liberal) / (PP(conservative) + PP(liberal))

Notice the denominator is the same in each case. This term is sometimes called the evidence. The challenge is to find the two partials. In this example, each partial has four terms multiplied together. Consider the first term in PP(conservative), which is P(barista | conservative), read as "the probability of a barista given that the person is a conservative." Bayes’ theorem gives:

P(barista | conservative) = Count(barista & conservative) / Count(conservative)

Here, Count is just a simple count of the number of applicable data items. In essence, this equation looks only at those people who are conservative, and finds what percentage of them are baristas. The quantity Count(barista & conservative) is called a joint count.

The next two terms for the partial for conservative, P(female | conservative) and PP(medium | conservative), can be found in the same way:

P(female | conservative) = Count(female & conservative) / Count(conservative)

P(medium | conservative) = Count(medium & conservative) / Count(conservative)

The last term for the partial of conservative is P(conservative), in words, "the probability that a person is a conservative." This can be found easily:

P(conservative) = Count(conservative) / (Count(conservative) + Count(liberal))

In other words, the probability that a person is a conservative is just the number of people who are conservatives, divided by the total number of people.

Putting this all together, if the problem is to find the probability that a person is a conservative and also the probability that the person is a liberal, if the person is a female barista with medium income, you need the partial for conservative and the partial for liberal. The partial for conservative is:

PP(conservative) =

P(barista | conservative) * P(female | conservative) * P(medium | conservative) * P(conservative) =

Count(barista & conservative) / Count(conservative) *

Count(female & conservative) / Count(conservative) *

Count(medium & conservative) / Count(conservative) *

Count(conservative) / (Count(conservative) + Count(liberal))

And the partial for liberal is:

PP(liberal) =

P(barista | liberal) * P(female | liberal) * P(medium | liberal) * P(liberal) =

Count(barista & liberal) / Count(liberal) *

Count(female & liberal) / Count(liberal) *

Count(medium & liberal) / Count(liberal) *

Count(liberal) / (Count(conservative) + Count(liberal))

And the two probabilities are:

P(conservative) = PP(conservative) / (PP(conservative) + PP(liberal))

P(liberal) = PP(liberal) / (PP(conservative) + PP(liberal))

Each piece of the puzzle is just a simple count, but there are many pieces. If you review the calculations carefully, you'll note that to compute any possible probability, for example P(liberal | cook & male & low) or P(conservative | analyst & female & high), you need the joint counts of every feature value with every dependent value, like "doctor & conservative", "male & liberal", "low & conservative", and so on. You also need the count of each dependent value.

To predict the political inclination of a female barista with medium income, the demo program computes P(conservative | barista & female & medium) and P(liberal | barista & female & medium) as follows.

First, the program scans the 24-item training data and finds all the relevant joint counts, and adds 1 to each count. The results are:

Count(barista & conservative) = 3 + 1 = 4

Count(female & conservative) = 3 + 1 = 4

Count(medium & conservative) = 11 + 1 = 12

Count(barista & liberal) = 2 + 1 = 3

Count(female & liberal) = 8 + 1 = 9

Count(medium & liberal) = 5 + 1 = 6

If you refer back to how partials are computed, you'll see they consist of several joint count terms multiplied together. If any joint count is 0, the entire product will be 0, and the calculation falls apart. Adding 1 to each joint count prevents this, and is called Laplacian smoothing.

Next, the program scans the 24-item training data and calculates the counts of the dependent variables and adds 3 (the number of features) to each:

Count(conservative) = 15 + 3 = 18

Count(liberal) = 9 + 3 = 12

Adding the number of features, 3 in this case, to each dependent variable count balances the 1 added to each of the three joint counts. Now the partials are computed like so:

PP(conservative) =

Count(barista & conservative) / Count(conservative) *

Count(female & conservative) / Count(conservative) *

Count(medium & conservative) / Count(conservative) *

Count(conservative) / (Count(conservative) + Count(liberal)) =

= (4 / 18) * (4 / 18) * (12 / 18) * (18 / 30)

= 0.2222 * 0.2222 * 0.6667 * 0.6000

= 0.01975 (rounded).

PP(liberal) =

Count(barista & liberal) / Count(liberal) *

Count(female & liberal) / Count(liberal) *

Count(medium & liberal) / Count(liberal) *

Count(liberal) / (Count(conservative) + Count(liberal)) =

= (3 / 12) * (9 / 12) * (6 / 12) * (12 / 30)

= 0.2500 * 0.7500 * 0.5000 * 0.4000

= 0.03750.

Using the partials, the final probabilities are computed:

P(conservative) = PP(conservative) / (PP(conservative) + PP(liberal))

= 0.01975 / (0.01975 + 0.03750)

= 0.3450 (rounded)

P(liberal) = PP(liberal) / (PP(conservative) + PP(liberal))

= 0.03750 / (0.01975 + 0.03750)

= 0.6550 (rounded)

If you refer to the screenshot in Figure 4-a, you'll see these two probability values displayed. Because the probability of liberal is greater than the probability of conservative, the prediction is that a female barista with medium income will most likely be a political liberal.

Demo Program Structure

The overall structure of the demo program, with a few minor edits to save space, is presented in Listing 4-a. To create the demo program, I launched Visual Studio and created a new C# console application project named NaiveBayes.

After the template code loaded into the editor, I removed all using statements at the top of the source code, except for the reference to the top-level System namespace, and the one to the Collections.Generic namespace. In the Solution Explorer window, I renamed file Program.cs to the more descriptive BayesProgram.cs, and Visual Studio automatically renamed class Program to BayesProgram.

using System; using System.Collections.Generic; namespace NaiveBayes { class BayesProgram { static void Main(string[] args) { Console.WriteLine("Begin Naive Bayes classification demo"); Console.WriteLine("Goal is to predict (liberal/conservative) from job, " + "sex and income"); string[][] rawData = new string[30][]; rawData[0] = new string[] { "analyst", "male", "high", "conservative" }; // etc. rawData[29] = new string[] { "barista", "male", "medium", "conservative" }; Console.WriteLine("The raw data is: "); ShowData(rawData, 5, true); Console.WriteLine("Splitting data into 80%-20% train and test sets"); string[][] trainData; string[][] testData; MakeTrainTest(rawData, 15, out trainData, out testData); // seed = 15 Console.WriteLine("Done"); Console.WriteLine("Training data: "); ShowData(trainData, 5, true); Console.WriteLine("Test data: "); ShowData(testData, 5, true); Console.WriteLine("Creating Naive Bayes classifier object"); BayesClassifier bc = new BayesClassifier(); bc.Train(trainData); Console.WriteLine("Done"); double trainAccuracy = bc.Accuracy(trainData); Console.WriteLine("Accuracy of model on train data = " + trainAccuracy.ToString("F4")); double testAccuracy = bc.Accuracy(testData); Console.WriteLine("Accuracy of model on test data = " + testAccuracy.ToString("F4")); Console.WriteLine("Predicting politics for job = barista, sex = female, " + "income = medium "); string[] features = new string[] { "barista", "female", "medium" }; string liberal = "liberal"; double pLiberal = bc.Probability(liberal, features); Console.WriteLine("Probability of liberal = " + pLiberal.ToString("F4")); string conservative = "conservative"; double pConservative = bc.Probability(conservative, features); Console.WriteLine("Probability of conservative = " + pConservative.ToString("F4")); Console.WriteLine("End Naive Bayes classification demo "); Console.ReadLine(); } // Main static void MakeTrainTest(string[][] allData, int seed, out string[][] trainData, out string[][] testData) { . . } static void ShowData(string[][] rawData, int numRows, bool indices) { . . } } // Program public class BayesClassifier { . . } } // ns |

Listing 4-a: Naive Bayes Demo Program Structure

The demo program class has two static helper methods. Method MakeTrainTest randomly splits the source data into an 80% training set and 20% test data. The 80-20 split is hard-coded, and you might want to parameterize the percentage of training data. Helper method ShowData displays an array-of-arrays style matrix of string values to the shell.

All the Bayes classification logic is contained in a single program-defined class named BayesClassifier. All the program logic is contained in the Main method. The Main method begins by setting up 30 hard-coded (job, sex, income, politics) data items in an array-of-arrays style matrix:

static void Main(string[] args)

{

Console.WriteLine("\nBegin Naive Bayes classification demo");

Console.WriteLine("Goal is to predict (liberal/conservative) from job, " +

"sex and income\n");

string[][] rawData = new string[30][];

rawData[0] = new string[] { "analyst", "male", "high", "conservative" };

rawData[1] = new string[] { "barista", "female", "low", "liberal" };

// etc.

rawData[29] = new string[] { "barista", "male", "medium", "conservative" };

. . .

In most realistic scenarios, your source data would be stored in a text file, and you would load it into a matrix in memory using a helper method named something like LoadData. Here, the dependent variable, politics, is assumed to be in the last column of the data matrix.

Next, the demo displays a part of the source data, and then creates the training and test sets:

Console.WriteLine("The raw data is: \n");

ShowData(rawData, 5, true);

Console.WriteLine("Splitting data into 80%-20% train and test sets");

string[][] trainData;

string[][] testData;

MakeTrainTest(rawData, 15, out trainData, out testData);

Console.WriteLine("Done \n");

The 5 argument passed to method ShowData is the number of rows to display, not including the last line of data, which is always displayed by default. The 15 argument passed to method MakeTrainTest is used as a seed value for a Random object, which randomizes how data items are assigned to either the training or test sets.

Next, the demo displays the first five, and last line, of the training and test sets:

Console.WriteLine("Training data: \n");

ShowData(trainData, 5, true);

Console.WriteLine("Test data: \n");

ShowData(testData, 5, true);

The true argument passed to ShowData directs the method to display row indices. In order to see the entire training data set so you can see how Bayes joint counts were calculated in the previous section, you could pass 23 as the number of rows.

Next, the classifier is created and trained:

Console.WriteLine("Creating Naive Bayes classifier object");

Console.WriteLine("Training classifier using training data");

BayesClassifier bc = new BayesClassifier();

bc.Train(trainData);

Console.WriteLine("Done \n");

Most of the work is done by method Train. In the case of naive Bayes, the Train method scans through the training data and calculates all the joint counts between feature values (like "doctor" and "high") and dependent values ("conservative" or "liberal"). The Train method also calculates the count of each dependent variable value.

After the model finishes the training process, the accuracy of the model on the training and test sets are calculated and displayed like so:

double trainAccuracy = bc.Accuracy(trainData);

Console.WriteLine("Accuracy of model on train data = " + trainAccuracy.ToString("F4"));

double testAccuracy = bc.Accuracy(testData);

Console.WriteLine("Accuracy of model on test data = " + testAccuracy.ToString("F4"));

Next, the demo indirectly makes a prediction by computing the probability that a female barista with medium income is a liberal:

Console.WriteLine("\nPredicting politics for job = barista, sex = female, "

+ "income = medium \n");

string[] features = new string[] { "barista", "female", "medium" };

string liberal = "liberal";

double pLiberal = bc.Probability(liberal, features);

Console.WriteLine("Probability of liberal = " + pLiberal.ToString("F4"));

Note that because this is a binary classification problem, only one probability is needed to make a classification decision. If the probability of either liberal or conservative is greater than 0.5, then because the sum of the probabilities of liberal and conservative is 1.0, the probability of the other political inclination must be less than 0.5, and vice versa.

The demo concludes by computing the probability that a female barista with medium income is a conservative:

. . .

string conservative = "conservative";

double pConservative = bc.Probability(conservative, features);

Console.WriteLine("Probability of conservative = " + pConservative.ToString("F4"));

Console.WriteLine("\nEnd Naive Bayes classification demo\n");

Console.ReadLine();

} // Main

An option to consider is to write a class method Predicted, which returns the dependent variable with higher probability.

Defining the BayesClassifer Class

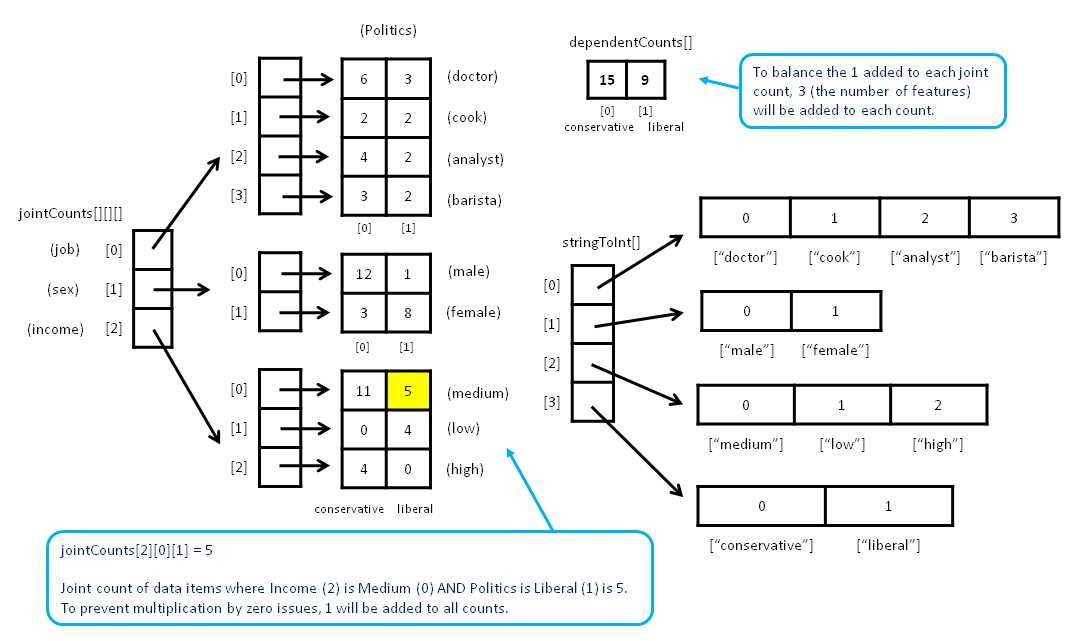

The structure of the program-defined class BayesClassifier is presented in Listing 4-b. The class has three data members and exposes four public methods. The key to understanding the implementation so that you can modify it if necessary to meet your own needs, is to understand the three data structures. The class data structures are illustrated in Figure 4-b.

public class BayesClassifier { private Dictionary<string, int>[] stringToInt; private int[][][] jointCounts; private int[] dependentCounts; public BayesClassifier() { . . } public void Train(string[][] trainData) { . . } public double Probability(string yValue, string[] xValues) { . . } public double Accuracy(string[][] data) { . . } } |

Listing 4-b: The BayesClassifier Class Structure

Data member stringToInt is an array of Dictionary objects. There is one Dictionary object for each column of data, and each Dictionary maps a string value, such as "barista" or "conservative", to a zero-based integer. For example, stringToInt[0]["doctor"] returns the integer value for feature 0 (job), value "doctor". The zero-based integer is used as an index into the other data structures.

Figure 4-b: Naive Bayes Key Data Structures

The integer index value for a string feature value is the order in which the feature value is encountered when the training method scans the training data. For example, for the demo program, the first five lines of the training data generated by method MakeTrainTest are:

[0] doctor male medium conservative

[1] cook female low liberal

[2] cook female low liberal

[3] analyst male high conservative

[4] barista male medium conservative

When method Train scans the first column of the training data, it will assign "doctor" = 0, "cook" = 1, "analyst" = 2, and "barista" = 3. Similarly, after scanning, the values "male" = 0, "female" = 1, "medium" = 0, "low" = 1, "high" = 2, "conservative" = 0, and "liberal" = 1 will be stored into the stringToInt Dictionary objects. Note that these assignments are likely to change if method MakeTrainTest uses a different seed value and generates a different set of training data.

Class data member jointCounts holds the joint count of each possible pair of feature value and dependent value. For the demo example, there are a total of nine feature values: analyst, barista, cook, doctor, male, female, low, medium, and high. There are two dependent values: conservative and liberal. Therefore there are a total of 9 * 2 = 18 joint counts for the example: (analyst & conservative), (analyst & liberal), (barista & conservative) . . . , (high & liberal).

The expression jointCounts[2][0][1] holds the count of training items where feature 2 (income) equals value 0 (medium), and dependent 1 (liberal). Recall that each joint count has 1 added to avoid multiplication by zero (Laplacian smoothing).

Class member dependentCounts holds the number of each dependent variable. For example, the expression dependentCounts[0] holds the number of training items where the dependent value is 0 (conservative). Recall that each cell in array dependentCounts has 3 (the number of features for the problem) added to balance the 1 added to each joint count.

The class constructor is short and simple:

public BayesClassifier()

{

this.stringToInt = null;

this.jointCounts = null;

this.dependentCounts = null;

}

In many OOP implementation scenarios, a class constructor allocates memory for the key member arrays and matrices. However, for naive Bayes, the number of cells to allocate in each of the three data structures will not be known until the training data is presented, so method Train will perform allocation.

One design alternative to consider is to pass the training data to the constructor. This design has some very subtle issues, both favorable and unfavorable, compared to having the training method perform allocation. A second design alternative is to pass the constructor integer parameters that hold the number of features, the number of distinct values in each feature, and the number of distinct dependent variable values.

The Training Method

Many machine classification algorithms work by creating some mathematical function that accepts feature values that are numeric and returns a numeric value that represents the predicted class. Examples of math-equation based algorithms include logistic regression classification, neural network classification, perceptron classification, support vector machine classification, and others. In these algorithms, the training process typically involves finding the values for a set of numeric constants, usually called the weights, which are used by the predicting equation.

Naive Bayes classification training does not search for a set of weights. Instead, the training simply scans the training data and calculates joint feature-dependent counts, and the counts of the dependent variable. These counts are used by the naive Bayes equations to compute the probability of a dependent class, given a set of feature values. In this sense, naive Bayes training is relatively simple.

The definition of method Train begins with:

public void Train(string[][] trainData)

{

int numRows = trainData.Length;

int numCols = trainData[0].Length;

this.stringToInt = new Dictionary<string, int>[numCols];

. . .

Method Train works directly with an array-of-arrays style matrix of string values. An alternative is to preprocess the training data, and convert each categorical value, such as "doctor", into its corresponding integer value (0) and store this data in an integer matrix.

The array of Dictionary objects is allocated with the number of columns, and so includes the dependent variable, political inclination, in the demo. An important assumption is that the dependent variable is located in the last column of the training matrix.

Next, the dictionaries for each feature are instantiated and populated:

for (int col = 0; col < numCols; ++col)

{

stringToInt[col] = new Dictionary<string, int>();

int idx = 0;

for (int row = 0; row < numRows; ++row)

{

string s = trainData[row][col];

if (stringToInt[col].ContainsKey(s) == false) // first time seen

{

stringToInt[col].Add(s, idx); // ex: doctor -> 0

++idx; // prepare for next string

}

} // each row

} // each col

The training matrix is processed column by column. As each new feature value is discovered in a column, its index, in variable idx, is saved. The .NET generic Dictionary collection is fairly sophisticated. The purpose of storing each value's index is so that the index can be looked up quickly. An alternative is to store each distinct column value in a string array. Then the cell index is the value's index. But this approach would require a linear search through the string array.

Next, the jointCounts data structure is allocated like this:

this.jointCounts = new int[numCols - 1][][]; // number features

for (int c = 0; c < numCols - 1; ++c) // not y-column

{

int count = this.stringToInt[c].Count;

jointCounts[c] = new int[count][];

}

for (int i = 0; i < jointCounts.Length; ++i)

for (int j = 0; j < jointCounts[i].Length; ++j)

jointCounts[i][j] = new int[2]; // binary classification

For me at least, when working with data structures such as jointCounts, it's absolutely necessary to sketch a diagram, similar to the one in Figure 4-b, to avoid making mistakes. Working from left to right, the first dimension of jointCounts is allocated with the number of features (three in the demo). Then each of those references is allocated with the number of distinct values for that feature. For example, feature 0, job, has four distinct values. The number of distinct values is stored as the Count property of the string-to-int Dictionary collection for the feature.

The last dimension of jointCounts is allocated with hard-coded size 2. This makes the class strictly a binary classifier. To extend the implementation to a multiclass classifier, you'd just replace the 2 with the number of distinct dependent variable values:

int numDependent = stringToInt[stringToInt.Length - 1].Count;

jointCounts[i][j] = new int[numDependent];

Next, each cell in jointCounts is initialized with 1 to avoid any cell being 0, which would cause trouble:

for (int i = 0; i < jointCounts.Length; ++i)

for (int j = 0; j < jointCounts[i].Length; ++j)

for (int k = 0; k < jointCounts[i][j].Length; ++k)

jointCounts[i][j][k] = 1;

Working with a data structure that has three index dimensions is not trivial, and can take some time to figure out. Next, method Train walks through each training data item and increments the appropriate cell in the jointCounts data structure:

for (int i = 0; i < numRows; ++i)

{

string yString = trainData[i][numCols - 1]; // dependent value

int depIndex = stringToInt[numCols - 1][yString]; // corresponding index

for (int j = 0; j < numCols - 1; ++j)

{

int attIndex = j; // aka feature, index

string xString = trainData[i][j]; // like "male"

int valIndex = stringToInt[j][xString]; // corresponding index

++jointCounts[attIndex][valIndex][depIndex];

}

}

Next, method Train allocates the data structure that stores the number of data items with each of the possible dependent values, and initializes the count in each cell to the number of features to use Laplacian smoothing:

this.dependentCounts = new int[2]; // binary

for (int i = 0; i < dependentCounts.Length; ++i) // Laplacian

dependentCounts[i] = numCols - 1; // number features

The hard-coded 2 makes this strictly a binary classifier, so you may want to modify the code to handle multiclass problems. As before, you can use the Count property of the Dictionary object for the column to determine the number of distinct dependent variable values. Here, the number of features is the number of columns of the training data matrix, less 1, to account for the dependent variable in the last column.

Method Train concludes by walking through the training data matrix, and counts and stores the number of each dependent variable value, conservative and liberal, in the demo:

. . .

for (int i = 0; i < trainData.Length; ++i)

{

string yString = trainData[i][numCols - 1]; // 'conservative' or 'liberal'

int yIndex = stringToInt[numCols - 1][yString]; // 0 or 1

++dependentCounts[yIndex];

}

return;

}

Here, I use an explicit return keyword for no reason other than to note that it is possible. In a production environment, it's fairly important to follow a standard set of style guidelines that presumably addresses things like using an explicit return with a void method.

Method Probability

Class method Probability returns the Bayesian probability of a specified dependent class value given a set of feature values. In essence, method Probability is the prediction method. For example, for the demo data, to compute the probability that a person has a political inclination of liberal, given that they have a job of doctor, sex of male, and income of high, you could call:

string[] featureVals = new string[] { "doctor", "male", "high" };

double pLib = bc.Probability("liberal", featureVals); // prob person is liberal

For binary classification, if this probability is greater than 0.5, you would conclude the person has a liberal political inclination. If the probability is less than 0.5, you'd conclude the person is a conservative.

Figure 4-c: Computing a Bayesian Probability

The Probability method uses a matrix, conditionals, and two arrays, unconditionals and partials, to store the values needed to compute the partials for each dependent variable value, and then uses the two partials to compute the requested probability. Those data structures are illustrated in Figure 4-c.

The method's definition begins:

public double Probability(string yValue, string[] xValues)

{

int numFeatures = xValues.Length;

double[][] conditionals = new double[2][]; // binary

for (int i = 0; i < 2; ++i)

conditionals[i] = new double[numFeatures];

. . .

If you refer to the section that explains how naive Bayes works, you'll recall that to compute a probability, you need two so-called partials, one for each dependent variable value. A partial is the product of conditional probabilities and one unconditional probability. For example, to compute the probability of liberal given barista and female, and medium, one partial is the product of P(barista | liberal), P(female | liberal), P(medium | liberal), and P(liberal).

In the demo, for just one partial, you need three conditional probabilities, one for each combination of the specified feature values and the dependent value. But to compute any probability for a binary classification problem, you need both partials corresponding to the two possible dependent variable values. Therefore, if there are two dependent variable values, and three features, you need 2 * 3 = 6 conditional probabilities to compute both partials.

The conditional probabilities are stored in the local matrix conditionals. The row index is the index of the dependent variable, and the column index is the index of the feature value. For example, conditionals[0][2] corresponds to dependent variable 0 (conservative) and feature 2 (income). Put another way, for the demo, the first row of conditionals holds the three conditional probabilities for conservative, and the second row holds the three conditional probabilities for liberal.

Next, array unconditionals, which holds the unconditional probabilities of each dependent variable value, is allocated, and the independent x-values and dependent y-value are converted from strings to integers:

double[] unconditionals = new double[2];

int y = this.stringToInt[numFeatures][yValue];

int[] x = new int[numFeatures];

for (int i = 0; i < numFeatures; ++i)

{

string s = xValues[i];

x[i] = this.stringToInt[i][s];

}

Because a variable representing the number of features is used so often in the code, a design alternative is to create a class member named something like numFeatures, rather than recreate it as a local variable for each method.

Next, the conditional probabilities are computed and stored using count information that was computed by the Train method:

for (int k = 0; k < 2; ++k) // each y-value

{

for (int i = 0; i < numFeatures; ++i)

{

int attIndex = i;

int valIndex = x[i];

int depIndex = k;

conditionals[k][i] = (jointCounts[attIndex][valIndex][depIndex] * 1.0) /

dependentCounts[depIndex];

}

}

Although the code here is quite short, it is some of the trickiest code I've ever worked with when implementing machine learning algorithms. For me at least, sketching out diagrams like those in Figures 4-b and 4-c is absolutely essential in order to write the code in the first place, and correct bugs later.

Next, method Probability computes the probabilities of each dependent value and stores those values:

int totalDependent = 0; // ex: count(conservative) + count(liberal)

for (int k = 0; k < 2; ++k)

totalDependent += this.dependentCounts[k];

for (int k = 0; k < 2; ++k)

unconditionals[k] = (dependentCounts[k] * 1.0) / totalDependent;

Notice that I qualify the first reference to member array dependentCounts using the this keyword, but I don't use this on the second reference. From a style perspective, I sometimes use this technique just to remind myself that an array, variable, or object is a class member.

Next, the partials are computed and stored:

double[] partials = new double[2];

for (int k = 0; k < 2; ++k)

{

partials[k] = 1.0; // because we are multiplying

for (int i = 0; i < numFeatures; ++i)

partials[k] *= conditionals[k][i];

partials[k] *= unconditionals[k];

}

Next, the sum of the two (for binary classification) partials is computed and stored, and the requested probability is computed and returned:

. . .

double evidence = 0.0;

for (int k = 0; k < 2; ++k)

evidence += partials[k];

return partials[y] / evidence;

}

Recall that the sum of partials is sometimes called the evidence term in naive Bayes terminology. Let me reiterate that the code for method probability is very tricky. The key to understanding this code, and many other machine learning algorithms, is having a clear picture (literally) of the data structures, arrays, and matrices used.

Method Accuracy

Method Accuracy computes how well the trained model predicts the dependent variable for a set of training data, or test data, which has known dependent variable values. The accuracy of the model on the training data gives you a rough idea of whether the model is effective or not. The accuracy of the model on the test data gives you a rough estimate of how well the model will predict when presented with new data, where the dependent variable value is not known.

The definition of method Accuracy begins:

public double Accuracy(string[][] data)

{

int numCorrect = 0;

int numWrong = 0;

int numRows = data.Length;

int numCols = data[0].Length;

. . .

Next, the method iterates through each data item and extracts the x-values—for example, "barista", "female", and "medium"—and extracts the known y-value—for example, "conservative". The x-values and the y-value are fed to the Probability method. If the computed probability is greater than 0.5, the model has made a correct classification:

. . .

for (int i = 0; i < numRows; ++i) // row

{

string yValue = data[i][numCols - 1]; // assumes y in last column

string[] xValues = new string[numCols - 1];

Array.Copy(data[i], xValues, numCols - 1);

double p = this.Probability(yValue, xValues);

if (p > 0.50)

++numCorrect;

else

++numWrong;

}

return (numCorrect * 1.0) / (numCorrect + numWrong);

}

A common design alternative is to use a different threshold value instead of the 0.5 used here. For example, suppose that for some data item, method Probability returns 0.5001. The classification is just barely correct in some sense. So you might want to count probabilities greater than 0.60 as correct, probabilities of less than 0.40 as wrong, and probabilities between 0.40 and 0.60 as inconclusive.

Converting Numeric Data to Categorical Data

Naive Bayes classification works with categorical data such as low, medium, and high for annual income, rather than numeric values such as $36,000.00. If a data set contains some numeric data and you want to apply naive Bayes classification, one approach is to convert the numeric values to categorical values. This process is called data discretization, or more informally, binning the data.

There are three main ways to bin data. The simplest, called equal width, is to create intervals, or “buckets,” of the same size. The second approach, used with equal frequency, is to create buckets so that each bucket has an (approximately) equal number of data values in it. The third approach is to create buckets using a clustering algorithm such as k-means, so that data values are grouped by similarity to each other.

Each of the three techniques has significant pros and cons, so there is no one clear best way to bin data. That said, equal-width binning is usually the default technique.

There are many different ways to implement equal-width binning. Suppose you want to convert the following 10 numeric values to either "small", "medium", "large", or "extra-large" (four buckets) using equal-width binning:

2.0, 3.0, 4.0, 5.0, 6.0, 8.0, 9.0, 10.0, 12.0, 14.0

Here, the data is sorted, but equal-width binning does not require this. First, the minimum and maximum values are determined:

min = 2.0

max = 14.0

Next, the width of each bucket is computed:

width = (max - min) / number-buckets

= (14.0 - 2.0) / 4

= 3.0

Next, a preliminary set of intervals that define each bucket are constructed:

[2.0, 5.0) [5.0, 8.0) [8.0, 11.0) [11.0, 14.0) -> interval data

[0] [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] -> cell index

{0} {1} {2} {3} -> bucket

Here, the notation [2.0, 5.0) means greater than or equal to 2.0, and also less than 5.0. Next, the two interval end points are modified to capture any outliers that may appear later:

[-inf, 5.0) [5.0, 8.0) [8.0, 11.0) [11.0, +inf) -> interval data

[0] [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] -> cell index

{0} {1} {2} {3} -> bucket

Here, -inf and +inf stand for negative infinity and positive infinity. Now the interval data can be used to determine the categorical equivalent of a numeric value. Value 8.0 belongs to bucket 2, so 8.0 maps to "large". If some new data arrives later, it can be binned too. For example, if some new value x = 12.5 appears, it belongs to bucket 3 and would map to "extra-large".

One possible implementation of equal-width binning can take the form of two methods: the first to create the interval data, and a second to assign a bucket or category to a data item. For example, a method to create interval data could begin as:

static double[] MakeIntervals(double[] data, int numBins) // bin numeric data

{

double max = data[0]; // find min & max

double min = data[0];

for (int i = 0; i < data.Length; ++i)

{

if (data[i] < min) min = data[i];

if (data[i] > max) max = data[i];

}

double width = (max - min) / numBins;

. . .

Static method MakeIntervals accepts an array of data to bin, and the number of buckets to create, and returns the interval data in an array. The minimum and maximum values are determined, and the bucket width is computed as described earlier.

Next, the preliminary intervals are created:

double[] intervals = new double[numBins * 2];

intervals[0] = min;

intervals[1] = min + width;

for (int i = 2; i < intervals.Length - 1; i += 2)

{

intervals[i] = intervals[i - 1];

intervals[i + 1] = intervals[i] + width;

}

Notice that when using the scheme described here, all the interval boundary values, except the first and last, are duplicated. It would be possible to store each boundary value just once. Duplicating boundary values may be mildly inefficient, but leads to code that is much easier to understand and modify.

And now, the first and last boundary values are modified so that the final interval data will be able to handle any possible input value:

. . .

intervals[0] = double.MinValue; // outliers

intervals[intervals.Length - 1] = double.MaxValue;

return intervals;

}

With this binning design, a partner method to perform the binning can be defined:

static int Bin(double x, double[] intervals)

{

for (int i = 0; i < intervals.Length - 1; i += 2)

{

if (x >= intervals[i] && x < intervals[i + 1])

return i / 2;

}

return -1; // error

}

Static method Bin does a simple linear search until it finds the correct interval. A design alternative is to do a binary search. Calling the binning methods could resemble:

double[] data = new double[] { 2.0, 3.0, . . , 14.0 };

double[] intervals = MakeIntervals(data, 4); // 4 bins

int bin = Bin(x, 9.5); // bucket for value 9.5

Comments

When presented with a machine learning classification problem, naive Bayes classification is often used first to establish baseline results. The idea is that the assumption of independence of predictor variables is almost certainly not true, so other, more sophisticated classification techniques should create models that are at least as good as a naive Bayes model.

One important area in which naive Bayes classifiers are often used is text and document classification. For example, suppose you want to classify email messages from customers into low, medium, or high priority. The predictor variables would be each possible word in the messages. Naive Bayes classification is surprisingly effective for this type of problem.

Chapter 4 Complete Demo Program Source Code

using System; using System.Collections.Generic; namespace NaiveBayes { class BayesProgram { static void Main(string[] args) { Console.WriteLine("\nBegin Naive Bayes classification demo"); Console.WriteLine("Goal is to predict (liberal/conservative) from job, " + "sex and income\n"); string[][] rawData = new string[30][]; rawData[0] = new string[] { "analyst", "male", "high", "conservative" }; rawData[1] = new string[] { "barista", "female", "low", "liberal" }; rawData[2] = new string[] { "cook", "male", "medium", "conservative" }; rawData[3] = new string[] { "doctor", "female", "medium", "conservative" }; rawData[4] = new string[] { "analyst", "female", "low", "liberal" }; rawData[5] = new string[] { "doctor", "male", "medium", "conservative" }; rawData[6] = new string[] { "analyst", "male", "medium", "conservative" }; rawData[7] = new string[] { "cook", "female", "low", "liberal" }; rawData[8] = new string[] { "doctor", "female", "medium", "liberal" }; rawData[9] = new string[] { "cook", "female", "low", "liberal" }; rawData[10] = new string[] { "doctor", "male", "medium", "conservative" }; rawData[11] = new string[] { "cook", "female", "high", "liberal" }; rawData[12] = new string[] { "barista", "female", "medium", "liberal" }; rawData[13] = new string[] { "analyst", "male", "low", "liberal" }; rawData[14] = new string[] { "doctor", "female", "high", "conservative" }; rawData[15] = new string[] { "barista", "female", "medium", "conservative" }; rawData[16] = new string[] { "doctor", "male", "medium", "conservative" }; rawData[17] = new string[] { "barista", "male", "high", "conservative" }; rawData[18] = new string[] { "doctor", "female", "medium", "liberal" }; rawData[19] = new string[] { "analyst", "male", "low", "liberal" }; rawData[20] = new string[] { "doctor", "male", "medium", "conservative" }; rawData[21] = new string[] { "cook", "male", "medium", "conservative" }; rawData[22] = new string[] { "doctor", "female", "high", "conservative" }; rawData[23] = new string[] { "analyst", "male", "high", "conservative" }; rawData[24] = new string[] { "barista", "female", "medium", "liberal" }; rawData[25] = new string[] { "doctor", "male", "medium", "conservative" }; rawData[26] = new string[] { "analyst", "female", "medium", "conservative" }; rawData[27] = new string[] { "analyst", "male", "medium", "conservative" }; rawData[28] = new string[] { "doctor", "female", "medium", "liberal" }; rawData[29] = new string[] { "barista", "male", "medium", "conservative" }; Console.WriteLine("The raw data is: \n"); ShowData(rawData, 5, true); Console.WriteLine("Splitting data into 80%-20% train and test sets"); string[][] trainData; string[][] testData; MakeTrainTest(rawData, 15, out trainData, out testData); // seed = 15 is nice Console.WriteLine("Done \n"); Console.WriteLine("Training data: \n"); ShowData(trainData, 5, true); Console.WriteLine("Test data: \n"); ShowData(testData, 5, true); Console.WriteLine("Creating Naive Bayes classifier object"); Console.WriteLine("Training classifier using training data"); BayesClassifier bc = new BayesClassifier(); bc.Train(trainData); // compute key count data structures Console.WriteLine("Done \n"); double trainAccuracy = bc.Accuracy(trainData); Console.WriteLine("Accuracy of model on train data = " + trainAccuracy.ToString("F4")); double testAccuracy = bc.Accuracy(testData); Console.WriteLine("Accuracy of model on test data = " + testAccuracy.ToString("F4")); Console.WriteLine("\nPredicting politics for job = barista, sex = female, " + "income = medium \n"); string[] features = new string[] { "barista", "female", "medium" }; string liberal = "liberal"; double pLiberal = bc.Probability(liberal, features); Console.WriteLine("Probability of liberal = " + pLiberal.ToString("F4")); string conservative = "conservative"; double pConservative = bc.Probability(conservative, features); Console.WriteLine("Probability of conservative = " + pConservative.ToString("F4")); Console.WriteLine("\nEnd Naive Bayes classification demo\n"); Console.ReadLine(); } // Main static void MakeTrainTest(string[][] allData, int seed, out string[][] trainData, out string[][] testData) { Random rnd = new Random(seed); int totRows = allData.Length; int numTrainRows = (int)(totRows * 0.80); int numTestRows = totRows - numTrainRows; trainData = new string[numTrainRows][]; testData = new string[numTestRows][]; string[][] copy = new string[allData.Length][]; // ref copy of all data for (int i = 0; i < copy.Length; ++i) copy[i] = allData[i]; for (int i = 0; i < copy.Length; ++i) // scramble order { int r = rnd.Next(i, copy.Length); string[] tmp = copy[r]; copy[r] = copy[i]; copy[i] = tmp; } for (int i = 0; i < numTrainRows; ++i) trainData[i] = copy[i]; for (int i = 0; i < numTestRows; ++i) testData[i] = copy[i + numTrainRows]; } // MakeTrainTest static void ShowData(string[][] rawData, int numRows, bool indices) { for (int i = 0; i < numRows; ++i) { if (indices == true) Console.Write("[" + i.ToString().PadLeft(2) + "] "); for (int j = 0; j < rawData[i].Length; ++j) { string s = rawData[i][j]; Console.Write(s.PadLeft(14) + " "); } Console.WriteLine(""); } if (numRows != rawData.Length-1) Console.WriteLine(". . ."); int lastRow = rawData.Length - 1; if (indices == true) Console.Write("[" + lastRow.ToString().PadLeft(2) + "] "); for (int j = 0; j < rawData[lastRow].Length; ++j) { string s = rawData[lastRow][j]; Console.Write(s.PadLeft(14) + " "); } Console.WriteLine("\n"); } static double[] MakeIntervals(double[] data, int numBins) // bin numeric data { double max = data[0]; // find min & max double min = data[0]; for (int i = 0; i < data.Length; ++i) { if (data[i] < min) min = data[i]; if (data[i] > max) max = data[i]; } double width = (max - min) / numBins; // compute width double[] intervals = new double[numBins * 2]; // intervals intervals[0] = min; intervals[1] = min + width; for (int i = 2; i < intervals.Length - 1; i += 2) { intervals[i] = intervals[i - 1]; intervals[i + 1] = intervals[i] + width; } intervals[0] = double.MinValue; // outliers intervals[intervals.Length - 1] = double.MaxValue; return intervals; } static int Bin(double x, double[] intervals) { for (int i = 0; i < intervals.Length - 1; i += 2) { if (x >= intervals[i] && x < intervals[i + 1]) return i / 2; } return -1; // error } } // Program public class BayesClassifier { private Dictionary<string, int>[] stringToInt; // "male" -> 0, etc. private int[][][] jointCounts; // [feature][value][dependent] private int[] dependentCounts; public BayesClassifier() { this.stringToInt = null; // need training data to know size this.jointCounts = null; // need training data to know size this.dependentCounts = null; // need training data to know size } public void Train(string[][] trainData) { // 1. scan training data and construct one dictionary per column int numRows = trainData.Length; int numCols = trainData[0].Length; this.stringToInt = new Dictionary<string, int>[numCols]; // allocate array

for (int col = 0; col < numCols; ++col) // including y-values { stringToInt[col] = new Dictionary<string, int>(); // instantiate Dictionary

int idx = 0; for (int row = 0; row < numRows; ++row) // each row of curr column { string s = trainData[row][col]; if (stringToInt[col].ContainsKey(s) == false) // first time seen { stringToInt[col].Add(s, idx); // ex: analyst -> 0 ++idx; } } // each row } // each col // 2. scan and count using stringToInt Dictionary this.jointCounts = new int[numCols - 1][][]; // do not include the y-value // a. allocate second dim for (int c = 0; c < numCols - 1; ++c) // each feature column but not y-column { int count = this.stringToInt[c].Count; // number possible values for column jointCounts[c] = new int[count][]; } // b. allocate last dimension = always 2 for binary classification for (int i = 0; i < jointCounts.Length; ++i) for (int j = 0; j < jointCounts[i].Length; ++j) { //int numDependent = stringToInt[stringToInt.Length - 1].Count; //jointCounts[i][j] = new int[numDependent]; jointCounts[i][j] = new int[2]; // binary classification }

// c. init joint counts with 1 for Laplacian smoothing for (int i = 0; i < jointCounts.Length; ++i) for (int j = 0; j < jointCounts[i].Length; ++j) for (int k = 0; k < jointCounts[i][j].Length; ++k) jointCounts[i][j][k] = 1;

// d. compute joint counts for (int i = 0; i < numRows; ++i) { string yString = trainData[i][numCols - 1]; // dependent value int depIndex = stringToInt[numCols - 1][yString]; // corresponding index for (int j = 0; j < numCols - 1; ++j) { int attIndex = j; string xString = trainData[i][j]; // an attribute value like "male" int valIndex = stringToInt[j][xString]; // corresponding integer like 0 ++jointCounts[attIndex][valIndex][depIndex]; } } // 3. scan and count number of each of the 2 dependent values this.dependentCounts = new int[2]; // binary for (int i = 0; i < dependentCounts.Length; ++i) // Laplacian init dependentCounts[i] = numCols - 1; // numCols - 1 = num features for (int i = 0; i < trainData.Length; ++i) { string yString = trainData[i][numCols - 1]; // conservative or liberal int yIndex = stringToInt[numCols - 1][yString]; // 0 or 1 ++dependentCounts[yIndex]; } return; // the trained 'model' is jointCounts and dependentCounts } // Train public double Probability(string yValue, string[] xValues) { int numFeatures = xValues.Length; // ex: 3 (job, sex, income) double[][] conditionals = new double[2][]; // binary for (int i = 0; i < 2; ++i) conditionals[i] = new double[numFeatures]; // ex: P('doctor' | conservative) double[] unconditionals = new double[2]; // ex: P('conservative'), P('liberal') // convert strings to ints int y = this.stringToInt[numFeatures][yValue]; int[] x = new int[numFeatures]; for (int i = 0; i < numFeatures; ++i) { string s = xValues[i]; x[i] = this.stringToInt[i][s]; } // compute conditionals for (int k = 0; k < 2; ++k) // each y-value { for (int i = 0; i < numFeatures; ++i) { int attIndex = i; int valIndex = x[i]; int depIndex = k; conditionals[k][i] = (jointCounts[attIndex][valIndex][depIndex] * 1.0) / dependentCounts[depIndex]; } } // compute unconditionals int totalDependent = 0; // ex: count(conservative) + count(liberal) for (int k = 0; k < 2; ++k) totalDependent += this.dependentCounts[k]; for (int k = 0; k < 2; ++k) unconditionals[k] = (dependentCounts[k] * 1.0) / totalDependent; // compute partials double[] partials = new double[2]; for (int k = 0; k < 2; ++k) { partials[k] = 1.0; // because we are multiplying for (int i = 0; i < numFeatures; ++i) partials[k] *= conditionals[k][i]; partials[k] *= unconditionals[k]; } // evidence = sum of partials double evidence = 0.0; for (int k = 0; k < 2; ++k) evidence += partials[k]; return partials[y] / evidence; } // Probability public double Accuracy(string[][] data) { int numCorrect = 0; int numWrong = 0; int numRows = data.Length; int numCols = data[0].Length; for (int i = 0; i < numRows; ++i) // row { string yValue = data[i][numCols - 1]; // assumes y in last column string[] xValues = new string[numCols - 1]; Array.Copy(data[i], xValues, numCols - 1); double p = this.Probability(yValue, xValues); if (p > 0.50) ++numCorrect; else ++numWrong; } return (numCorrect * 1.0) / (numCorrect + numWrong); } } // class BayesClassifier } // ns |

- 1800+ high-performance UI components.

- Includes popular controls such as Grid, Chart, Scheduler, and more.

- 24x5 unlimited support by developers.