CHAPTER 2

Date and time

Date and time settings might seem to be trivial, but they actually vary a lot. Without a proper library parsing date,time strings would be confusing.

The string “1/2/2003” can actually be interpreted both as second of January and first of February depending on which country you live in. Here in Sweden we do not use that format at all, but instead “2003-02-01” (yes, the zeroes should be included).

As for the time, it typically only differs in whether a 12-hour or 24-hour format should be used.

The standard format

There is an ISO standard that specifies how date and time should be formatted. The standard is called ISO8601. The common denominator is that the order should be from the most significant to least significant.

Dates should be formatted as:

YYYY-MM-DD => 2013-05-13

Time should be formatted as:

HH:MM:SS => 23:00:10

And finally the combination:

YYYY-MM-DDTHH:MM:SS => 2013-05-13T23:00:10

String representation

Sometimes you have to represent a date as a string, typically when you exchange information with other systems through some sort of API, or use UI binding.

Using just date/time strings like “2013-01-01 01:39:20” is ambiguous since there is no way of telling what time zone the date is for. You therefore have to use a format that removes the ambiguity.

I recommend you use one of the following two formats.

RFC1123

The first format is the one from RFC1123 and is used by HTTP and other Internet protocols. It looks like this:

Mon, 13 May 2013 20:46:37 GMT

HTTP requires you to always use GMT as time zone while the original specification allows you to use any of the time zones specified in RFC822. I usually follow HTTP, as it makes the handling easier (i.e. use UTC everywhere except in the user interaction; more about that later).

RFC3339

RFC3399 is based upon several standards like ISO8601. Its purpose is to make the date rules less ambiguous. It even includes ABNF grammar that explains the format that ISO8601 uses.

To make it simple: use the letter “T” between the date and time, and end the string with the time zone offset from UTC. UTC itself is indicated by using Z as a suffix.

UTC time:

2013-05-13T20:46:37Z

Central European time (CET)

2013-05-13T20:46:37+01:00

.NET

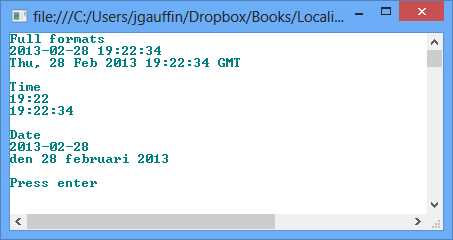

The date/time formatting is controlled by the CultureInfo.CurrentCulture property. Try to avoid using your own formatting (i.e. manually specify the format), as it rarely works with different cultures. Instead just make sure that the correct culture has been specified and use the formatting methods which are demonstrated below.

var currentTime = DateTime.Now; Console.WriteLine("Full formats"); Console.WriteLine(currentTime.ToString()); Console.WriteLine(currentTime.ToString("R")); Console.WriteLine(); Console.WriteLine("Time"); Console.WriteLine(currentTime.ToShortTimeString()); Console.WriteLine(currentTime.ToLongTimeString()); Console.WriteLine(); Console.WriteLine("Date"); Console.WriteLine(currentTime.ToShortDateString()); Console.WriteLine(currentTime.ToLongDateString()); Console.WriteLine(); |

The result is shown in the following figure.

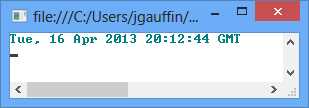

RFC1123

There are some formatters for DateTime.ToString() that can be used, such as “R,” which will return an RFC1123 time as mentioned in the previous section.

Console.WriteLine(DateTime.UtcNow.ToString("R")); |

The output is:

Do note that “R” defines that the date is GMT no matter what time zone you are in. It’s therefore very important that you use UtcNow, as in the example above. I’ll come back to what UTC/GMT means in the next chapter.

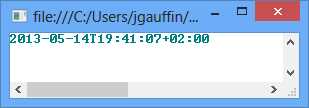

RFC3339

As the DateTime structure in C# does not have time zone information, it’s impossible for it to generate a proper RFC3339 string.

The code below uses an extension method, which is defined in the appendix of this book.

var cetTime = DateTime.Now.ToRFC3339("W. Europe Standard Time"); |

The code generates the following string (Daylight saving time is active):

Time zones are discussed in more detail in a later chapter.

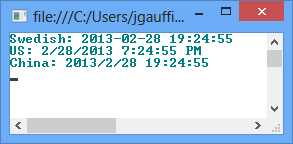

Formatting by culture

You can also format dates by specifying cultures explicitly.

var currentTime = DateTime.Now; Console.WriteLine("Swedish: {0}", currentTime.ToString(swedish)); var us = new CultureInfo("en-us"); Console.WriteLine("US: {0}", currentTime.ToString(us)); var china = new CultureInfo("zh-CN"); Console.WriteLine("China: {0}", currentTime.ToString(china)); |

The result follows:

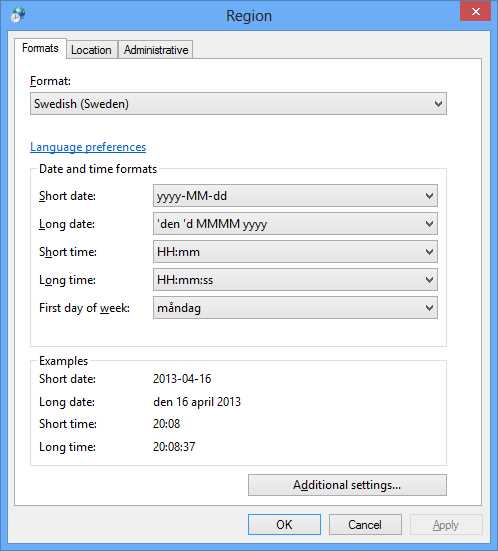

If you are interested in seeing how each culture formats its dates, go to the Control Panel and open up the Region applet as the following figure demonstrates:

Simply select a new culture to see its formats.

Parsing dates

Parsing dates can be a challenge, especially if you do not know in advance the culture on the user’s system, or if it is different from the one in the application server (for instance in web applications).

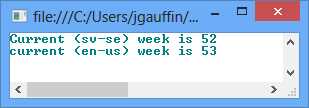

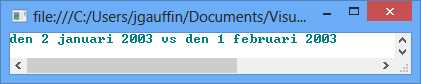

Here is a simple example that shows how the exact same string can be interpreted differently.

class Program { static void Main(string[] args) { var date = DateTime.Parse("1/2/2003", new CultureInfo("sv")); var date2 = DateTime.Parse("1/2/2003", new CultureInfo("fr")); Console.WriteLine(date.ToLongDateString() + " vs " + date2.ToLongDateString()); } } |

The sample output is:

The parser is quite forgiving, as “1/2/2003” is not a valid date string in Sweden. The real format is “YYYY-MM-DD”. This also illustrates another problem: If anyone had asked me to mentally parse “1/2/2003,” I would have said the first of February and nothing else.

A forgiving parser can be a curse as it can interpret values incorrectly. As in such, you may think that you have a correct date when you don’t.

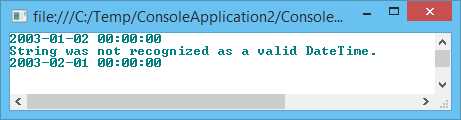

You can force exact parsing if you know the kind of format (as in long or short format):

class Program { static void Main(string[] args) { var swedishCulture = new CultureInfo("sv-se"); // incorrect var date = DateTime.Parse("1/2/2003", swedishCulture); Console.WriteLine(date); // throws an exception try { var date2 = DateTime.ParseExact("1/2/2003", swedishCulture.DateTimeFormat.ShortDatePattern, swedishCulture); } catch (Exception ex) { Console.WriteLine(ex.Message); } // OK. var date3 = DateTime.ParseExact("2003-02-01", swedishCulture.DateTimeFormat.ShortDatePattern, swedishCulture); Console.WriteLine(date3); Console.ReadLine(); } } |

Notice that the format is retrieved from .NET and is nothing that I supply through a string constant. It’s a nice way to get around the forgiving parser to be sure that the parsed value is correct.

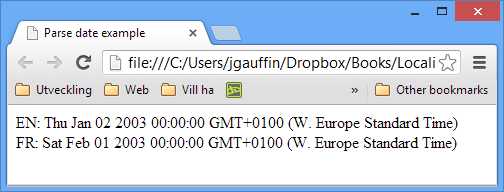

JavaScript

We use the Globalize plugin to handle date/time in HTML pages.

<html> <head> <title>Parse date example</title> <script src="http://ajax.aspnetcdn.com/ajax/jquery/jquery-1.9.0.min.js"></script> <script src="http://ajax.aspnetcdn.com/ajax/globalize/0.1.1/globalize.min.js"></script> <script src="http://ajax.aspnetcdn.com/ajax/globalize/0.1.1/cultures/globalize.cultures.js"></script> </head> <body> <script type="text/javascript"> Globalize.culture("en"); var enResult = Globalize.parseDate("1/2/2003", null, ”fr”); Globalize.culture("fr"); var frResult = Globalize.parseDate("1/2/2003"); document.writeln("EN: " + enResult + "<br>"); document.writeln("FR: " + frResult + "<br>"); </script> </body> </html> |

The result is:

You can also pass the culture as a parameter:

<script type="text/javascript"> var enResult = Globalize.parseDate("1/2/2003", null, "en"); var frResult = Globalize.parseDate("1/2/2003", null, "fr"); document.writeln("EN: " + enResult + "<br>"); document.writeln("FR: " + frResult + "<br>"); </script> |

- 1800+ high-performance UI components.

- Includes popular controls such as Grid, Chart, Scheduler, and more.

- 24x5 unlimited support by developers.