CHAPTER 4

Adding Contacts

Version 2, Section 2.2 of the specification initially states this simple algorithm for dealing adding contacts:

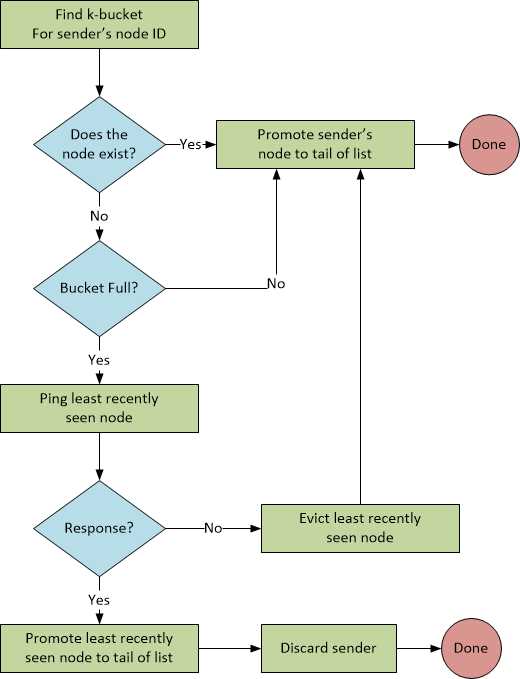

“When a Kademlia node receives any message (request or reply) from another node, it updates the appropriate k-bucket for the sender’s node ID. If the sending node already exists in the recipient’s k-bucket, the recipient moves it to the tail of the list. If the node is not already in the appropriate k-bucket and the bucket has fewer than k entries, then the recipient just inserts the new sender at the tail of the list. If the appropriate k-bucket is full, however, then the recipient pings the k-bucket’s least-recently seen node to decide what to do. If the least recently seen node fails to respond, it is evicted from the k-bucket and the new sender inserted at the tail. Otherwise, if the least-recently seen node responds, it is moved to the tail of the list, and the new sender’s contact is discarded.”

Let’s define a few terms for clarity:

- Head of the list: The first entry in the list.

- Tail of the list: The last entry in the list.

- The appropriate k-bucket for the sender’s node ID: The k-bucket for which the sender’s node ID is in the range of the k-bucket.

Figure 2 is a flowchart of what the spec says.

Figure 2: The Add Contact Algorithm

This seems reasonable, and the spec goes on to state:

“k-buckets effectively implement a least-recently seen eviction policy, except that live nodes are never removed from the list. This preference for old contacts is driven by our analysis of Gnutella trace data collected by Saroiu, et. al. ... The longer a node has been up, the more likely it is to remain up another hour. By keeping the oldest live contacts around, k-buckets maximize the probability that the nodes they contain will remain online. A second benefit of k-buckets is that they provide resistance to certain DoS attacks. One cannot flush the nodes’ routing state by flooding the system with new nodes. Kademlia nodes will only insert the new nodes in the k-buckets when old nodes leave the system.”

We also observe that this has nothing to do with binary trees, which is something version 2 of the spec introduced. This is basically a hangover from version 1 of the spec. However, Section 2.4 states something slightly different:

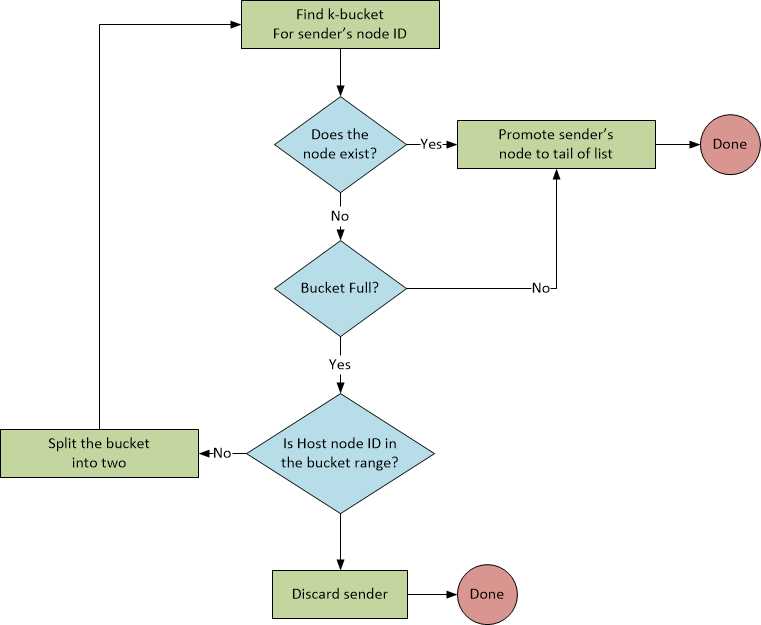

“Nodes in the routing tree are allocated dynamically, as needed. Initially, a node u’s routing tree has a single node—one k-bucket covering the entire ID space. When u learns of a new contact, it attempts to insert the contact in the appropriate k-bucket. If that bucket is not full, the new contact is simply inserted. Otherwise, if the k-bucket’s range includes u’s own node ID, then the bucket is split into two new buckets, the old contents divided between the two, and the insertion attempt repeated. If a k-bucket with a different range is full, the new contact is simply dropped.”

Again, a definition of terms is useful:

- u’s routing tree: The host’s bucket list.

- If a k-bucket with a different range is full: Meaning, a k-bucket that does not include u’s own node ID.

Bucket-splitting

The purpose of allowing a bucket to split if it contains the host’s node ID is so that the host keeps a list of nodes that are “close to it”—closeness is defined essentially by the integer difference of the node IDs, not the XOR difference (more on this whole XOR thing later).

So, this algorithm looks like Figure 3.

Figure 3: Bucket Splitting

What happened to pinging the least-seen contact and replacing it? Again, the spec then goes on to say:

“One complication arises in highly unbalanced trees. Suppose node u joins the system and is the only node whose ID begins 000. Suppose further that the system already has more than k nodes with prefix 001. Every node with prefix 001 would have an empty k-bucket into which u should be inserted, yet u’s bucket refresh would only notify k of the nodes. To avoid this problem, Kademlia nodes keep all valid contacts in a subtree of size at least k nodes, even if this requires splitting buckets in which the node’s own ID does not reside. Figure 5 illustrates these additional splits.”

A few more clarifications:

- A subtree of size at least k nodes: The reason the subtree contains “at least k nodes” is that when the parent is split, it creates two subtrees whose total number of nodes begins with k but may contain more than k nodes as nodes are added to each branch (or the branch splits again into two more branches.)

- Even if this requires splitting buckets in which the node’s own ID does not reside: Not only is this contradictory, but there’s no explanation of what “even if this requires” means. How do you code this?

This section of the specification apparently creates much confusion—I found several links with people asking about this section. It’s unfortunate that the original authors themselves do not answer these questions. Jim Dixon has a very interesting response on The Mail Archive ,[11] which I present in full here:

“The source of confusion is that the 13-page version of the Kademlia uses the same term to refer to two different data structures. The first is well-defined: k-bucket i contains zero to k contacts whose XOR distance is [2^i..2^(i+1)). It cannot be split. The current node can only be in bucket zero, if it is present at all. In fact, its presence would be pointless or worse.

The second thing referred to as a k-bucket doesn’t have the same properties. Specifically, the current node must be present, it wanders from one k-bucket to another, these k-buckets can be split, and there are sometimes ill-defined constraints on the characteristics of subtrees of k-buckets, such as the requirement that “Kademlia nodes keep all valid contacts in a subtree of size of at least k nodes, even if this requires splitting buckets in which the node’s own ID does not reside” (section 2.4, near the end).

In a generous spirit, you might say that the logical content of the two descriptions is the same. However, for someone trying to implement Kademlia, the confusion of terms causes headaches—and leads to a situation where all sorts of things are described as Kademlia, because they can be said to be, if you are of a generous disposition. However, not surprisingly, they don’t interoperate.”

So, my decision, given the ambiguity of the spec, is to ignore this, because as you will see next, there is yet another version of how contacts are added.

In Section 4.2, on Accelerated Lookups, we have a different specification for how contacts are added:

“Section 2.4 describes how a Kademlia node splits a k-bucket when the bucket is full and its range includes the node’s own ID. The implementation, however, also splits ranges not containing the node’s ID, up to b - 1 levels. If b = 2, for instance, the half of the ID space not containing the node’s ID gets split once (into two ranges); if b = 3, it gets split at two levels into a maximum of four ranges, etc. The general splitting rule is that a node splits a full k-bucket if the bucket’s range contains the node’s own ID or the depth d of the k-bucket in the routing tree satisfies d (mod b) != 0.”

Another term to consider:

Depth. According to the spec: “The depth is just the length of the prefix shared by all nodes in the k-bucket’s range.” Do not confuse that with this statement in the spec: “Define the depth, h, of a node to be 160 - i, where i is the smallest index of a nonempty bucket.” The former is referring to the depth of a k-bucket, the latter the depth of the node.

With regard to the definition of depth, does this mean “the length of prefix shared by any node that would reside in the k-bucket’s range,” or does it mean “the length of a prefix shared by all nodes currently in the k-bucket”?

If we look at Brian Muller’s implementation in Python, we see the latter case.

Code Listing 17: Depth is Determined by the Shared Prefixes

def depth(self): sp = sharedPrefix([bytesToBitString(n.id) for n in self.nodes.values()]) return len(sp) def sharedPrefix(args): i = 0 while i < min(map(len, args)): if len(set(map(operator.itemgetter(i), args))) != 1: break i += 1 return args[0][:i] |

Here, the depth is determined by the shared prefixes in the nodes. So, when we use the following algorithm to determine whether a bucket can be split.

Code Listing 18: Bucket Split Logic

kbucket.HasInRange(ourID) || ((kbucket.Depth() % Constants.B) != 0) |

What is this actually doing?

- First, the HasInRange is testing whether our node ID is close to the contact’s node ID. If our node ID is in the range of the bucket associated with the contact’s node ID, then we know the two nodes are “close” in terms of the integer difference. Initially, the range spans the entire 2160 ID space, so everybody is “close.” This test of closeness is refined as new contacts are added.

- Regarding the depth mod 5 computation, I asked Brian Muller this question: “Is the purpose of the depth to limit the number of ‘new’ nodes that a host will maintain (ignoring for the moment the issue of pinging an old contact to see if can be replaced)?” He replied: “Yes! The idea is that a node should know about nodes spread across the network—though definitely not all of them. The depth is used as a way to control how ‘deep’ a node’s understanding of the network is (and the number of nodes it knows about).”

The depth to which the bucket has split is based on the number of bits shared in the prefix of the contacts in the bucket. With random IDs, this number will initially be small, but as bucket ranges become more narrow from subsequent splits, more contacts will begin the share the same prefix and the bucket when split, will result in less “room” for new contacts. Eventually, when the bucket range becomes narrow enough, the number of bits shared in the prefix of the contacts in the bucket reaches the threshold b, which the spec says should be 5.

Failing to add yourself to a peer: self-correcting

Let’s say you’re a new node and you want to register yourself with a known peer, but that peer is maxed out for the number of contacts that it can hold in the particular bucket for your ID—the depth is b. In this case, you will not be added to the peer’s contact list. The Kademlia spec indicates that peers that fail to be added to a bucket be placed into a queue of pending contacts, which we discuss later. Regardless, not being added to a peer’s bucket list is not really an issue. Whether you are successfully added as a contact or not, you will receive back “nearby” peers. Any time you contact those peers (to store a value, for example), all the peers that you contact will try to add your contact. When one succeeds, your contact ID will be disseminated slowly through the network.

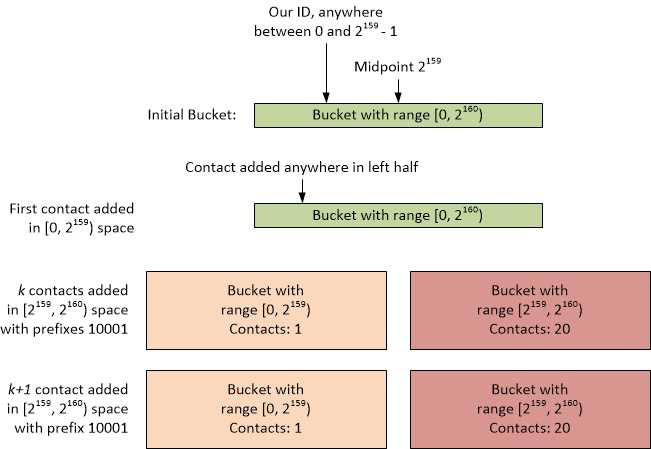

Degrading a Kademlia peer

Given a peer with both an ID and a single contact ID of less than 2159, it will initially split once for 20 contacts that are added having IDs greater than 2159. All of those 20 contacts having IDs greater than 2159 will go in the second bucket. The peer ID will not be in this second bucket range. If those contacts in the second bucket have IDs where the number of shared bits is b, and therefore b mod b == 0, any new contact in the range of the second bucket will not be added.

Figure 4: Degrading Adding Contacts

We can verify this with a unit test.

Code Listing 19: Forcing Add Contact Failure

[TestMethod] public void ForceFailedAddTest() { Contact dummyContact = new Contact(new VirtualProtocol(), ID.Zero); ((VirtualProtocol)dummyContact.Protocol).Node = IBucketList bucketList = SetupSplitFailure(); Assert.IsTrue(bucketList.Buckets.Count == 2, "Bucket split should have occurred."); Assert.IsTrue(bucketList.Buckets[0].Contacts.Count == 1, Assert.IsTrue(bucketList.Buckets[1].Contacts.Count == 20, // This next contact should not split the bucket as depth == 5 and therefore adding // Any unique ID >= 2^159 will do. byte[] id = new byte[20]; id[19] = 0x80; Contact newContact = new Contact(dummyContact.Protocol, new ID(id)); bucketList.AddContact(newContact); Assert.IsTrue(bucketList.Buckets.Count == 2, Assert.IsTrue(bucketList.Buckets[0].Contacts.Count == 1, Assert.IsTrue(bucketList.Buckets[1].Contacts.Count == 20, // Verify CanSplit -> Evict did not happen. Assert.IsFalse(bucketList.Buckets[1].Contacts.Contains(newContact), } |

What we’ve effectively done is break Kademlia, as the peer will no longer accept half of the possible ID range. As long as the peer ID is outside the range of a bucket whose shared prefix mod b is 0, we can continue this process by adding contacts with a shared prefixes (assume b==5) 01xxx, 001xx, 0001x, and 00001, and again for every multiple of b bits. If a peer has a “small” ID, you can easily prevent it from accepting new contacts within half of its bucket ranges.

There are several ways to mitigate this:

- IDs should not be created by the user; they should be assigned by the library. Of course, given the open-source nature of all these implementations, enforcing this is impossible.

- A contact’s ID should be unique for its network address—in other words, a malicious peer should not be able to create multiple contacts simply by providing a unique ID in its contact request.

- One might consider increasing b as i in 2i increases. There might be some justification for this, as the range 2159 through 2160 - 1 contains half the possible contacts, one might allow the depth for bucket splitting to be greater than the recommended b = 5.

Implementation

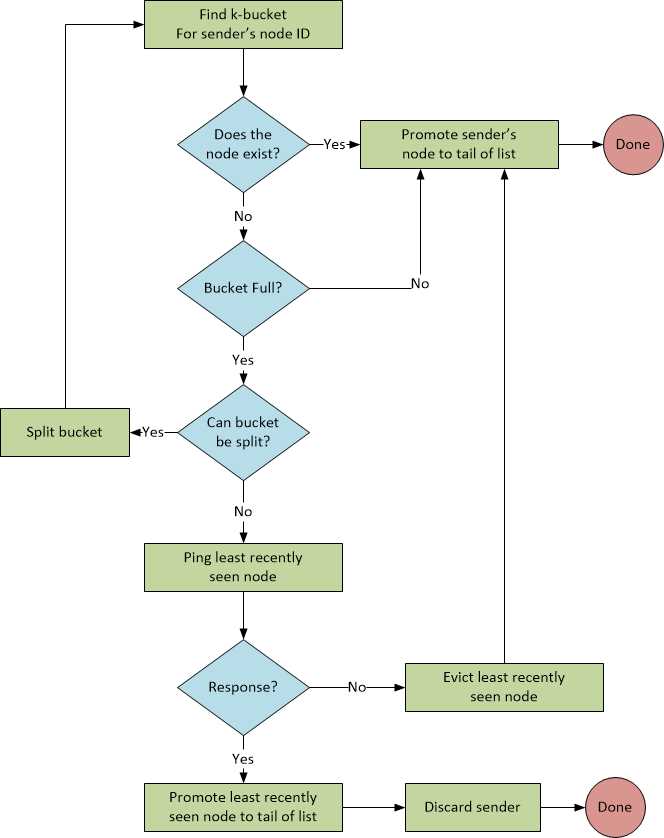

Figure 5 shows the flowchart of what we are initially implementing.

Figure 5: Adding Contacts with Bucket Splitting

As I’m using Brian Muller’s implementation as the authority with regards to the spec, we’ll go with how he coded the algorithm and will (eventually) incorporate the fallback where we discard nodes in a full k-bucket that don’t respond to a ping—but that’s later.

The BucketList class implements the algorithm to add a contact. Note that the lock statements ensure bucket lists are manipulated synchronously, as the peer server will be receiving commands asynchronously.

Code Listing 20: The AddContact Method Implementation

public void AddContact(Contact contact) { Validate.IsFalse<OurNodeCannotBeAContactException>(ourID == contact.ID, contact.Touch(); // Update the LastSeen to now. lock (this) { KBucket kbucket = GetKBucket(contact.ID); if (kbucket.Contains(contact.ID)) { // Replace the existing contact, updating the network info and kbucket.ReplaceContact(contact); } else if (kbucket.IsBucketFull) { if (CanSplit(kbucket)) { // Split the bucket and try again. (KBucket k1, KBucket k2) = kbucket.Split(); int idx = GetKBucketIndex(contact.ID); buckets[idx] = k1; buckets.Insert(idx + 1, k2); buckets[idx].Touch(); buckets[idx + 1].Touch(); AddContact(contact); } else { } } else { // Bucket isn’t full, so just add the contact. kbucket.AddContact(contact); } } } |

Later, this will be extended to handle delayed eviction and adding new contacts that can’t fit in the bucket to a pending queue.

We have a few helper methods in this class as well.

Code Listing 21: Helper Methods

protected virtual bool CanSplit(KBucket kbucket) { lock (this) { return kbucket.HasInRange(ourID) || ((kbucket.Depth() % Constants.B) != 0); } } { lock (this) { return buckets.FindIndex(b => b.HasInRange(otherID)); } } /// Returns number of bits that are in common across all contacts. /// If there are no contacts, or no shared bits, the return is 0. /// </summary> public int Depth() { bool[] bits = new bool[0]; if (contacts.Count > 0) { // Start with the first contact. bits = contacts[0].ID.Bytes.Bits().ToArray(); contacts.Skip(1).ForEach(c => bits = SharedBits(bits, c.ID)); } return bits.Length; } /// <summary> /// Returns a new bit array of just the shared bits. /// </summary> protected bool[] SharedBits(bool[] bits, ID id) { bool[] idbits = id.Bytes.Bits().ToArray(); // Useful for viewing the bit arrays. //string sbits1 = System.String.Join("", bits.Select(b => b ? "1" : "0")); //string sbits2 = System.String.Join("", idbits.Select(b => b ? "1" : "0")); int q = Constants.ID_LENGTH_BITS - 1; int n = bits.Length - 1; List<bool> sharedBits = new List<bool>(); while (n >= 0 && bits[n] == idbits[q]) { sharedBits.Insert(0, (bits[n])); --n; --q; } return sharedBits.ToArray(); } |

The method CanSplit is virtual, so you can provide a different implementation.

The majority of the remaining work is done in the KBucket class.

Code Listing 22: The Split Method

public (KBucket, KBucket) Split() { BigInteger midpoint = (Low + High) / 2; KBucket k1 = new KBucket(Low, midpoint); KBucket k2 = new KBucket(midpoint, High); Contacts.ForEach(c => { // <, because the High value is exclusive in the HasInRange test. KBucket k = c.ID < midpoint ? k1 : k2; k.AddContact(c); }); return (k1, k2); } |

Recall that the ID is stored as a little-endian value, and the prefix is most significant bits, so we have to work the ID backwards, n-1 to 0. Also note the implementation of the Bytes property in the ID class:

Code Listing 23: The ID.Bytes Property

/// <summary> /// The array returned is in little-endian order (lsb at index 0) /// </summary> public byte[] Bytes { get { // Zero-pad msb's if ToByteArray length != Constants.LENGTH_BYTES byte[] bytes = new byte[Constants.ID_LENGTH_BYTES]; byte[] partial = id.ToByteArray().Take(Constants.ID_LENGTH_BYTES).ToArray(); partial.CopyTo(bytes, 0); return bytes; } } |

Unit tests

Here are a few basic unit tests. The VirtualProtocol and VirtualStorage classes will be discussed later. Also note that the constructors for Contact don’t match the code in the basic framework shown previously, as the unit tests here are reflective of the final implementation of the code base.

Code Listing 24: AddContact Unit Tests

[TestMethod] public void UniqueIDAddTest() { Contact dummyContact = new Contact(new VirtualProtocol(), ID.Zero); ((VirtualProtocol)dummyContact.Protocol).Node = BucketList bucketList = new BucketList(ID.RandomIDInKeySpace, dummyContact); Constants.K.ForEach(() => bucketList.AddContact( Assert.IsTrue(bucketList.Buckets.Count == 1, Assert.IsTrue(bucketList.Buckets[0].Contacts.Count == Constants.K, } [TestMethod] public void DuplicateIDTest() { Contact dummyContact = new Contact(new VirtualProtocol(), ID.Zero); ((VirtualProtocol)dummyContact.Protocol).Node = BucketList bucketList = new BucketList(ID.RandomIDInKeySpace, dummyContact); ID id = ID.RandomIDInKeySpace; bucketList.AddContact(new Contact(null, id)); bucketList.AddContact(new Contact(null, id)); Assert.IsTrue(bucketList.Buckets.Count == 1, "No split should have taken place."); Assert.IsTrue(bucketList.Buckets[0].Contacts.Count == 1, } [TestMethod] public void BucketSplitTest() { Contact dummyContact = new Contact(new VirtualProtocol(), ID.Zero); ((VirtualProtocol)dummyContact.Protocol).Node = BucketList bucketList = new BucketList(ID.RandomIDInKeySpace, dummyContact); Constants.K.ForEach(() => bucketList.AddContact( bucketList.AddContact(new Contact(null, ID.RandomIDInKeySpace)); Assert.IsTrue(bucketList.Buckets.Count > 1, } |

Distribution tests reveal importance of randomness

What happens instead if we randomize the ID based on a random distribution of bucket slot rather than a simple random ID? By this, we mean distributing the IDs evenly across the bucket space, not the ID space. Some helper methods:

Code Listing 25: Randomize Bits Helper Methods

public ID RandomizeBeyond(int bit, int minLsb = 0, bool forceBit1 = false) { byte[] randomized = Bytes; ID newid = new ID(randomized); // TODO: Optimize for (int i = bit + 1; i < Constants.ID_LENGTH_BITS; i++) { newid.ClearBit(i); } // TODO: Optimize for (int i = minLsb; i < bit; i++) { if ((rnd.NextDouble() < 0.5) || forceBit1) { newid.SetBit(i); } } return newid; } /// <summary> /// Clears the bit n, from the little-endian LSB. /// </summary> public ID ClearBit(int n) { byte[] bytes = Bytes; bytes[n / 8] &= (byte)((1 << (n % 8)) ^ 0xFF); id = new BigInteger(bytes.Append0()); // for continuations. return this; } /// <summary> /// Sets the bit n, from the little-endian LSB. /// </summary> public ID SetBit(int n) { byte[] bytes = Bytes; bytes[n / 8] |= (byte)(1 << (n % 8)); id = new BigInteger(bytes.Append0()); // for continuations. return this; } |

Also, a random ID generator, as in Code Listing 26.

Code Listing 26: RandomID and RandomIDInKeySpace

public static ID RandomIDInKeySpace { get { byte[] data = new byte[Constants.ID_LENGTH_BYTES]; ID id = new ID(data); // Uniform random bucket index. int idx = rnd.Next(Constants.ID_LENGTH_BITS); // 0 <= idx <= 159 // Remaining bits are randomized to get unique ID. id.SetBit(idx); id = id.RandomizeBeyond(idx); return id; } } /// <summary> /// Produce a random ID. /// </summary> public static ID RandomID { get { byte[] buffer = new byte[Constants.ID_LENGTH_BYTES]; rnd.NextBytes(buffer); return new ID(buffer); } } |

Let’s look at what happens when we assign a node ID as one of 2i where 0 <= i < 160 and add 3,200 integer random contact IDs. Here’s the unit test, which outputs the count of contacts added to each node ID in the set of i.

Code Listing 27: Distribution with Random IDs

[TestMethod] public void DistributionTestForEachPrefix() { Contact dummyContact = new Contact(new VirtualProtocol(), ID.Zero); ((VirtualProtocol)dummyContact.Protocol).Node = Random rnd = new Random(); StringBuilder sb = new StringBuilder(); 160.ForEach((i) => { BucketList bucketList = 3200.ForEach(() => { Contact contact = new Contact(new VirtualProtocol(), ID.RandomID); ((VirtualProtocol)contact.Protocol).Node = bucketList.AddContact(contact); }); int contacts = bucketList.Buckets.Sum(b => b.Contacts.Count); sb.Append(i + "," + contacts + CRLF); }); File.WriteAllText("prefixTest.txt", sb.ToString()); } |

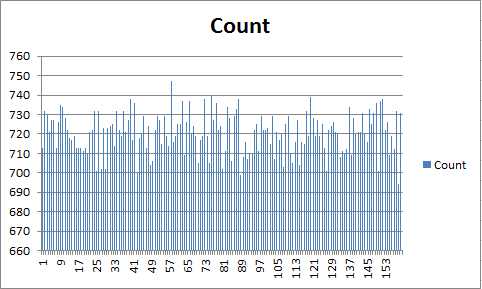

Figure 6: Random ID Distribution

That looks fairly reasonable.

Compare this with the distribution of contact counts when the contact ID is selected from a random prefix with randomized bits after the prefix, as opposed to a random integer ID.

Code Listing 28: Distribution with Random Prefixes

[TestMethod] public void DistributionTestForEachPrefixWithRandomPrefixDistributedContacts() { Contact dummyContact = ((VirtualProtocol)dummyContact.Protocol).Node = StringBuilder sb = new StringBuilder(); 160.ForEach((i) => { BucketList bucketList = Contact contact = new Contact(new VirtualProtocol(), ID.RandomIDInKeySpace); ((VirtualProtocol)contact.Protocol).Node = 3200.ForEach(() => bucketList.AddContact(contact)); int contacts = bucketList.Buckets.Sum(b => b.Contacts.Count); sb.Append(i + "," + contacts + CRLF); }); File.WriteAllText("prefixTest.txt", sb.ToString()); } |

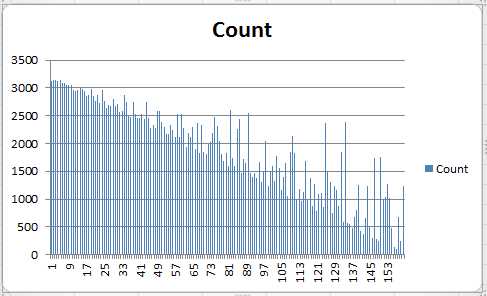

Figure 7: Distributed Prefix Distribution

If there was a question as to whether to choose a node ID based on an even distribution in the prefix space versus simply a random integer ID, I think this clearly demonstrates that a random integer ID is the best choice.

- 1800+ high-performance UI components.

- Includes popular controls such as Grid, Chart, Scheduler, and more.

- 24x5 unlimited support by developers.