CHAPTER 5

Multithreading

Multithreading is a technique for programming more than one execution unit at the same time. Computers traditionally run with a single CPU executing the code. The CPU runs through the instructions one after another, jumping to various methods. CPUs execute code very quickly, but there is a limit to the speed any CPU can execute. A modern CPU can execute billions of instructions every second, but it is very costly to increase this execution speed—the hardware begins to require extreme measures to prevent the CPU from melting or catching on fire (for instance, water and even liquid nitrogen have been used to cool very fast CPUs).

Thankfully, we can greatly improve the performance of our CPUs without increasing the clock speed of the units. Instead, manufacturers add multiple execution units to a single die (die is simply a word for the physical object inside the computer upon which the CPU is etched). The units are called cores, and each can be thought of as being a complete CPU of its own.

Figure 10: Multithreading

Figure 10 shows a hypothetical, best-case scenario for multicore CPUs. On the left, we see a single core performing two tasks. A single core executes Task A first, and when Task A is finished, it executes Task B. Both tasks take the CPU five seconds to execute, and thus the total execution time is 10 seconds.

In the middle of Figure 10, the dual-core CPU can execute Tasks A and B at the same time by allowing each to be executed by one of its two cores. Each task takes five seconds to compute, but the tasks are executed at the same time, therefore they will finish at the same time, taking five seconds (plus a small amount of time for overhead).

Finally, the right side of Figure 10 shows a quad-core CPU. It is sometimes possible to split tasks into several sections, and in the diagram, we have assigned one of the four cores of our quad-core CPU to execute a half of Tasks A or B. Execution of half of a task takes 2.5 seconds, and all four cores will finish after approximately 2.5 seconds. This speed represents four times the performance of the single core CPU.

Figure 10 shows a hypothetical case. This is the best possible case, and in practice tasks do not often split in half so easily. However, you can see that as the number of cores increases, the ability of the cores to share the workload becomes very useful. It is often practical to improve the performance of our applications by 200% or even 400% by employing multithreading and by cleverly allocating our workloads to different cores. As we shall see, typically cores are required to communicate and coordinate their actions with each other, and often we do not get a straight 100% improvement in speed when we add another core.

Multithreading is an extremely vast and complex topic, and we will only scratch the very surface in this text, but you should practice your multithreading skills frequently because the future of computing is very heavily dependent on efficient multithreading.

Threads

A thread is an execution unit. For instance, when our application is run by the user, the JVM will create a single, main thread for us to begin executing the main method. It may also create several background threads for garbage collection (to delete unneeded objects behind the scenes), and other background tasks. The main thread begins by executing the code from the main method, as we have seen many times.

Call stack

When a thread executes code, it jumps to various points in the code while it calls the methods. These method calls can be nested (i.e. a method can call itself; it can call methods). Methods may require parameters to be passed, and they can specify their own local variables. In order to return from methods in the correct order, to pass parameters to and from methods, and to keep track of the local variables of methods, an area of RAM is allocated called the “call stack.” Each thread has its own call stack, and threads can potentially call any sequence of different methods.

Eclipse shows a simple version of the program’s call stack when it pauses at a breakpoint. Figure 11 shows a screenshot of the Debug window while a program runs. The information presented is the name of the running application class (MainClass). The thread is called [main], and it suspended due to a breakpoint at line 18 in the Animal class source code file. The next lines are the call stack. The program has executed the Animal.print method, along with the method before that—the MainClass.main method (which called the Animal.print method).

Figure 11: Debug Window

In Java, threads are resource-heavy. It takes time for the system to create and run a new thread, and creating a new thread results in the allocation of other system resources (such as RAM for the call stack). We should never attempt to create hundreds of threads, nor should we attempt to create and kill threads within a tight loop. Thread creation is slow, and the number of threads a system can concurrently execute is always limited by the physical hardware (i.e. the number of cores in the system, the amount of RAM, the speed of the CPU, etc.). There are several methods by which multiple threads can be created in Java, and we will look at two—implementing the Runnable interface and extending the Thread class.

Note: When we create a new thread, it will often be executed on a new core within the CPU. However, cores and threads are not always directly associated. Often, the operating system switches threads on and off the cores, giving each thread a small amount of time (called a time-slice) in order to execute some portion of code. Even a single core CPU can emulate multithreading by quickly switching between threads, allocating to each thread some time-slice on the physical core.

Implementing Runnable

In order to use multiple threads, we can create a class that implements the Runnable interface. This allows us to create a class with a private member thread. The Runnable interface defines an abstract method called run that we must implement in our derived classes. When we create a new thread, it will execute this method (probably using a different core in the CPU to the core that executes the main method). Note that we can create two, four or even eight threads, even if the hardware only has a dual-core CPU. But be careful—as mentioned, threads are resource-heavy, and if you try to create 100 or 1000 threads, your program will not run blisteringly fast, it will stop completely and possibly crash the program, if not the entire system (requiring a reboot).

Code Listing 5.0: MainClass

public class MainClass { public static void main(String[] args) { // Define Thready objects: Thready t1 = new Thready("Ned"); Thready t2 = new Thready("Kelly"); // Start the threads: t1.initThread(); t2.initThread(); } } |

Code Listing 5.1: Thready Class

public class Thready implements Runnable { // Private member variables: private Thread thread; private String name; // Constructor: public Thready(String name) { this.name = name; System.out.println("Created thread: " + name); } // Init and start thread method: public void initThread() { System.out.println("Initializing thread: " + name); thread = new Thread(this, name); thread.start(); } // Overridden run method: public void run() { // Print initial message: System.out.println("Running thread: " + name); // Count to 10: for(int i = 0; i < 10; i++) { System.out.println("Thread " + name + " counted " + i); try { // Wait for 1 second: Thread.sleep(1000); } catch (Exception e) { System.out.println("Error: " + e.getMessage()); } } } } |

Figure 12: Output from Ned and Kelly

Figure 12 shows one possible output from the program in Code Listings 5.0 and 5.1. Code Listing 5.1 shows the Thready class that implements the Runnable interface, and it defines the run method, which is required to implement Runnable. The class defines a Thread object called thread, which we instantiate in the method called initThread. Then we call the Thread object’s start method, which will in turn call the Runnable interface’s run method. In the run method, we count from 0 to nine, pausing for one second between each number. Upon running the application, you will see the two threads (created in the MainClass from Code Listing 5.0) counting slowly to nine.

There are several very important facts about the program from Code Listings 5.0 and 5.1:

- The threads count at the same time, and thus the program takes only about 10 seconds to execute.

- The exact timing and order of the counting threads is not known to us (Ned could inexplicably count slightly faster than Kelly, or vice versa).

- If you run this application on a multicore desktop PC, there is a high likelihood that Ned and Kelly (our threads) will run on different cores inside the machine.

Concurrency

The point above about not knowing the exact order of execution is important! When we look at the code from Code Listings 5.0 and 5.1, we cannot tell what will happen. Ned could count faster, or Kelly could count faster (the two will count at approximately one second per number, but on the nanosecond level, one thread will always beat the other).

The two threads could count completely randomly—they could swap leader every number, so that each time we execute the application, we might get a different output. Ned and Kelly are called “concurrent.” If you cannot determine in which order the threads will execute simply by looking at the code, then the code is concurrent. It is never safe to assume an order of execution for concurrent threads (in fact, concurrency means we cannot assume the order!). We must be extremely careful when we coordinate concurrent threads. We cannot tell what will happen when we look at the code because the CPU’s task is extremely complicated—it is executing the operating system and hundreds of background tasks. It executes time-slices of each thread and switches the background processes on and off the physical cores. Somewhere, in this mess of instructions, our humble little Ned and Kelly threads will be given some time to execute on a core, then they are put to sleep for some other program to execute on the core. We have no practical way of guessing in which order our threads will execute, thus our threads are concurrent. Generally, we hope that the CPU is not too busy executing background tasks, and when we create threads, we aim for them to be executed in their entirety, uninterrupted and simultaneously, but we cannot guarantee that this will happen.

Thread coordination

When the tasks that our threads perform are completely independent, the algorithm is called embarrassingly parallel. Embarrassingly parallel algorithms are the best-case scenario for multithreading because we can split the workload perfectly and threads do not need to communicate or synchronize in any way. This means each thread can perform its assigned task as quickly as possible with no interruptions and without worrying about what any other threads are doing. In real-world applications, many algorithms do not split so perfectly into two or more parts. The workload of each thread is typically not 100% independent from that of the other threads. Threads need to communicate.

In order for one thread to communicate with another, the threads need a shared resource. Imagine Ned and Kelly wish to perform two tasks—BoilWater and PourCoffee. The problem is that we need the water boiled before the coffee is poured. So, if Ned is assigned the task of boiling the water, and Kelly is assigned the task of pouring the coffee, then Ned needs some way to indicate to Kelly that the water has been boiled. And Kelly must wait for some signal from Ned before she pours the coffee.

Low-level concurrency pitfalls

Let us take moment to examine some important concepts and pitfalls involved in concurrent programming. This section might seem particularly low level, but nothing in concurrent programming makes sense unless we know why we must watch our step.

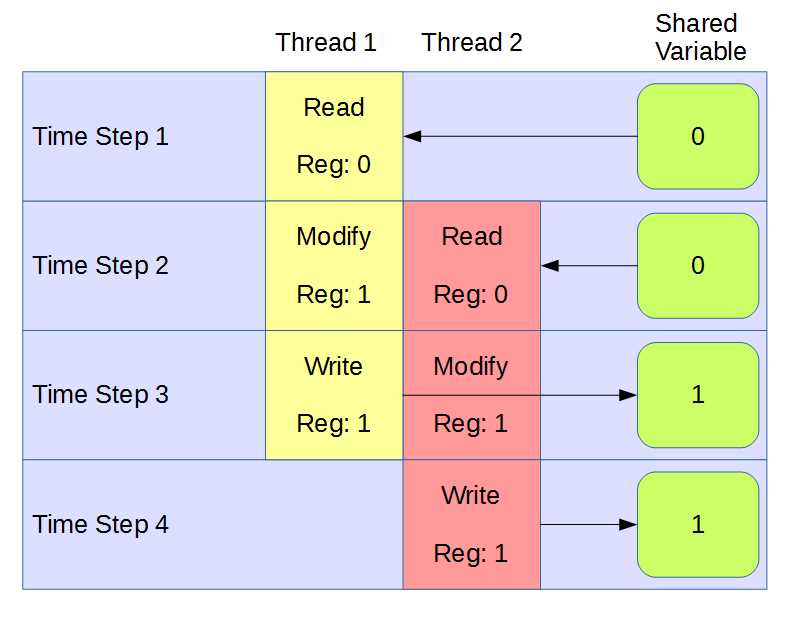

In the current context, resources are variables. Shared resources are variables to which multiple threads can read or write. When we share variables between threads, we need to be careful not to allow race conditions. A race condition occurs when two threads might potentially alter a variable at the same time. Imagine two threads trying to increment a shared resource that is initially set to 0. The operation appears trivial—we want two threads to increment the variable, so the result should be two. The trouble is, the act of incrementing a variable is not atomic. If an operation is not atomic, it can be broken into several steps. These steps are called the Read/Modify/Write cycle. A thread first reads the current value of the variable from RAM, then it modifies it by performing the increment on a temporary copy of the variable, and finally it writes the result back to the actual variable in RAM.

Modern CPUs perform almost all operations on variables using a Read/Modify/Write cycle because they do not have the ability to perform arithmetic on the data in RAM. RAM does not work that way—it allows two operations: read a value at some address or write a value to some address. It does not allow a CPU to add two values together or subtract one from the other. Therefore, the CPU requests some variable from RAM, storing a copy in its internal registers (a register is a variable inside the CPU). The CPU then performs the arithmetic operation on this copy and finally sends the results back to RAM.

Figure 13 shows an example of a race condition. The example shows two threads trying to increment the shared variable from 0 to 2 at the same time. The two threads execute one step at a time, and the time is listed along the left side of the diagram. Both threads read the value of the shared variable as 0, increment this to 1 using their internal register, and write the 1 as the result. We can see that the final result at time-step 4 is 1 instead of 2. But this is not the only possibility—the CPU is making up the results as it schedules the threads for execution, and the result is out of the programmer’s control.

Figure 13: Race Condition

In order to use shared resources, we must be very careful to ensure that there are no race conditions. This often means that only one thread is allowed access to a shared resource at a time. In order to create shared resources in Java, we can use the synchronized keyword. Any method marked as synchronized will allow exactly one thread to execute the method at a time. This means that if we modify a variable from within a synchronized code block, we can be guaranteed that only one thread at a time is allowed access.

Mutex

Mutual Exclusion, or a mutex, is a parallel primitive. It is a mechanism used in parallel programming that allows only one thread at a time to access some section of code. A mutex is used to build critical sections in our code that only one thread at a time is allowed to execute. No mutex is provided in the standard Java libraries, so, as an exercise, we will create one.

The mutex has two methods associated with it—grabMutex and releaseMutex. The purpose of a mutex is to allow only one thread at a time to complete the call to grabMutex. Once a thread has the mutex (or, in other words, has successfully completed a call to grabMutex), any other threads that try to call grabMutex will block—they will stop execution and wait for the mutex to be released. Thus, any operations performed while a thread has the mutex are atomic. They cannot be interrupted by any other thread until the mutex is released.

In Java, we must synchronize on an object. That is, we must use some object as a lock in order to successfully design a mutually exclusive code block.

Code Listing 5.2: Main Method for Mutex

public class MainClass { public static void main(String[] args) { // Create three threads: Thready t1 = new Thready("Ned"); Thready t2 = new Thready("Kelly"); Thready t3 = new Thready("Pole");

// init and run the threads. t1.initThread(); t2.initThread(); t3.initThread();

// Wait for the threads to finish: while(t1.isRunning()) { } while(t2.isRunning()) { } while(t3.isRunning()) { } // Check what the counter is: System.out.println("All done!" + Thready.getJ()); } } |

Let’s now look at three versions of the Thready class, each with a slightly different run method. I will only include the code for the complete class in the first example, as Code Listing 5.3 shows the complete code for the Thready class, although in this code I have purposely designed the class so that the threads are prone to race conditions.

Code Listing 5.3: Thready Class with Race Conditions

public class Thready implements Runnable { // A shared resource: public class Counter { private int j;

public Counter() { j = 0; }

public int getJ() { return j; } } // Thready member variables private Thread thread; private String name; private boolean running = true;

// Static shared resource: private static Counter counter = null; // Getters: public static int getJ() { return counter.getJ(); }

public boolean isRunning() { return running; } // Constructor public Thready(String name) { // Create the shared resource if(counter == null) counter = new Counter(); // Assign name this.name = name; // Print message System.out.println("Created thread: " + name); } public void initThread() { // Print message System.out.println("Initializing thread: " + name); // Create thread thread = new Thread(this, name); // Call run thread.start(); } public void run() { for(int q = 0; q < 10000; q++) { counter.j++; // RACE CONDITION!!! } running = false; } } |

Notice the line marked with comment “RACE CONDITION!!!” in Code Listing 5.3. The main method in Code Listing 5.2 creates and executes three threads, Ned, Kelly, and Pole. All three threads try to increment the shared counter.j variable in their run methods, but they do so at the same time with no coordination. Race conditions are disastrous, and to prove that they are much more than mere theory, run the program a few times and witness the final value that the main method reports. The main method will almost never count up to the intended value of 30,000 (i.e. the value we expect when three threads each increment a variable 10,000 times). It reports 12,672 and 13,722. In fact, it seems to report anything it wants, and we know why—the threads are incrementing their own copies of the shared resource and only occasionally writing a successful update! Let’s take a moment to implement a mutex and see if we can fix the accesses to this shared resource.

Code Listing 5.4: Using a Mutex 1 (The Slow Way)

public void run() { for(int q = 0; q < 10000; q++) { synchronized (counter) { counter.j++; } } running = false; } |

The second version of the run method is slightly better (Code Listing 5.4). We have employed the synchronized keyword and locked the code inside the loop using the shared resource as the key (this lock is our mutex). The synchronized keyword takes a resource to synchronize with, and it is followed by a code block. Only one of the three threads is able to execute inside the synchronized code block at a time, therefore the line of code “counter.j++” is a critical section. The threads will wait until the lock (or the mutex) is released, and they will take turns to enter the critical section, increment counter.j, then release the lock.

Grabbing and releasing the lock takes time. Ultimately, we want threads to work independently for as long as possible before they synchronize. If you run the application (and please do not) with the new version of the run method, you may have to wait a very long time for the threads to throw the lock about 30,000 times and increment counter.j all the way to 30,000. They will eventually finish, but it could take 10 minutes or it could take an hour. Code Listing 5.5 shows a far better way of doing this.

Note: You can also mark a method with the synchronized keyword. When we mark a method as synchronized, we are saying that the method can only be used by one thread at a time. However, we must be very careful because a synchronized method actually implicitly synchronizes with the “this” keyword as the object for the lock. That is—if we have a synchronized method in a class and we try to create multiple threads of that class, when we call the method, the threads will not synchronize because each of them is using itself as the lock.

Code Listing 5.5: Using a Mutex 2 (The Fast Way)

public void run() { synchronized (counter) { for(int q = 0; q < 10000; q++) { counter.j++; } } running = false; } |

In Code Listing 5.5, we place the lock outside the for loop. This is the only difference, but it makes a huge difference in performance. Now, when a thread grabs the lock, it increments counter.j 10,000 times before it releases the lock. This means the lock is grabbed three times instead of 30,000, and the performance is far better.

Code Listing 5.5 might seem like the obvious choice from the examples I have presented, and in the present case, I would advise this. But the program has a big drawback—the increments are now happening sequentially. The threads are not performing their workloads at the same time, each one is either incrementing the counter or waiting for the lock. There is no point to incrementing a counter in this way because the main thread can perform the increment without allocating any new threads at all. Concurrent programming is a juggling act between coordinating threads to perform independent tasks simultaneously and allowing them to synchronize/communicate so that we avoid race conditions and the programmer remains in control of the outcome.

This example is problematic because incrementing a counter is not a suitable task for multithreading. Selecting which tasks in a program are suitable for designing concurrently is one of the most important aspects of multithreading.

Extending the Thread class

We’ve looked at implementing Runnable for multithreading. The second method for multithreading is to extend the Thread class. In Code Listings 5.6 and 5.7, a new thread is created by extending the Thread class and executing the Thread.start() method. The objective of our threads is to find factors of the shared number x. The threads do so by partitioning the values from 2 to sqrt(x) into two parts, and each thread checks for factors in half of this range. This program uses the brute force method for finding factors, and it is not intended to be a useful program for solving the factoring problem.

Code Listing 5.6: Main Method

// MainClass.java public class MainClass { public static void main(String[] args) { // Define some threads: Thready thread0 = new Thready(0); Thready thread1 = new Thready(1); // Set the value to factor: Thready.x = 36847153; // Start the threads: thread0.start(); thread1.start();

// Wait for the threads to finish. while(thread0.isAlive()) { } while(thread1.isAlive()) { } // Print out the factors the threads found: System.out.println( "Smallest Factor found by thread0: " + thread0.smallestFactor); System.out.println( "Smallest Factor found by thread1: " + thread1.smallestFactor); } } |

Code Listing 5.7: Extending the Thread Class

// The class Extends the Thread class. public class Thready extends Thread { // Shared resource public static int x; public int id; // Smallest factor found by this thread: public int smallestFactor = -1;

// Constructor public Thready(int id) { this.id = id; }

// Run method public void run() { // Figure out the root: int rootOfX = (int)Math.sqrt(x) + 1;

// Figure out the start and finish points: int start = (rootOfX / 2) * id; int finish = start + (rootOfX / 2);

// If the number is even: if(x % 2 == 0) { smallestFactor = 2; return; } // Don't check 0 and 1 as a factor: if(start == 0 || start == 1) start = 3;

// Only check odd numbers: if(start % 2 == 0) start++;

// Try to find a factor. for(int i = start; i < finish; i+=2) { if(x % i == 0) { smallestFactor = i; break; } } } } |

In general, using the Java Runnable mechanism is preferred to extending the Thread class for most scenarios. A detailed comparison of the two techniques is outside the scope of this e-book, but you can find many interesting discussions on the topic at Stack Overflow (http://stackoverflow.com/).

- 1800+ high-performance UI components.

- Includes popular controls such as Grid, Chart, Scheduler, and more.

- 24x5 unlimited support by developers.