CHAPTER 5

Data Types and Variables

Memory

In Java, as with all computer programming languages, we can read and write data to various memory spaces. A memory space is simply an area in which we can save and retrieve information. One of the most useful memory spaces that we can read and write to is called system RAM. RAM stands for Random Access Memory. It is a type of volatile memory used for temporary storage (volatile means it is cleared when the system reboots).

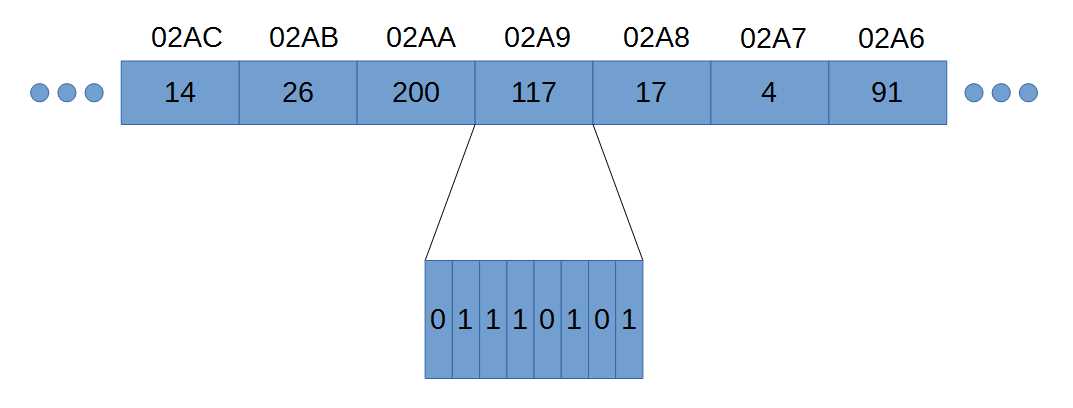

RAM is nothing more than a long string of 0s and 1s. The 0s and 1s are organized into bytes of 8 bits each (a bit is short for binary digit—it is a single 0 or 1). See Figure 35 for an illustration of several bytes in RAM.

Figure 35: RAM

Figure 35 shows seven bytes in RAM. Each byte in RAM has an address written above the boxes (real addresses on modern computers have 16 hexadecimal digits instead of the four I’ve used in the illustration). The addresses are simply consecutive numbers counting up as we move through RAM from right to left. The addresses are written in hexadecimal (so we have 02A8 instead of 680—hexadecimal is not important at the moment).

Note: In Java, we do not have access to the addresses in RAM. This is one of the biggest differences between Java and related languages C and C++. Accessing RAM directly with addresses can be dangerous—it is easy to accidentally address the wrong bytes and cause bugs in our programs. So, Java does not allow direct access to RAM.

Along with an address, each byte in RAM also has a value (such as 14, 100, or 117 in Figure 35). As you can see, RAM is a collection of bytes, each with an address so that we can reference the bytes, and a value, so that we can read and write some information.

In Figure 35, the byte at address 02A9 is zoomed in, and we can see the individual bits that make up the number 117 as written out in the binary counting system. In binary, bits are read from left to right, the same way we read normal decimal numbers. So, the bit on the left is the most significant (as in the 6 in 684), and the bit on the right is the least significant (as in the 4 in 684).

Programming a computer is difficult when we reference RAM by addresses (and Java does not allow us direct access to bytes by their addresses). Addresses are simply long hexadecimal numbers, and they do not appear meaningful to humans.

As programmers, we need to manipulate and control hundreds, thousands, and even millions of bytes in RAM, and doing so with addresses is extremely difficult. Therefore, instead of referencing RAM by addresses, we name certain points in RAM and use the names instead of the addresses. These named points in RAM are called variables. A variable is literally a point that we have named and in which we can read and write in RAM. Variables often contain multiple bytes—for instance, an int variable in Java is built from four consecutive bytes and can be used to store larger numbers than a single byte can store.

Each variable in Java has a data type that is an indication as to what type of manipulations we will perform on the particular spot in RAM or which type of information the bits represent. For instance, we might wish to use a variable for floating-point computations such as 3.4+7.8, or we might wish to perform some operation with whole numbers (integers) such as 3+7.

Primitive data types

The most fundamental, basic building blocks of data types in Java are called the primitive data types (sometimes just primitives). They are used to build more complex data types such as classes and enumerations. When we declare variables in Java, we must state their data types. Java is a type-safe language, which means that once a data type is given to a variable, we cannot later change the type.

Table 1: Primitive Data Types

Name | Type | Size (Bytes) | Size (Bits) | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

byte | Integer | 1 | 8 | -128 | 127 |

short | Integer | 2 | 16 | -32768 | 23767 |

int | Integer | 4 | 32 | -2147483648 | 2147483647 |

long | Integer | 8 | 64 | -263 | 263-1 |

float | Float | 4 | 32 | -3.4x1038 | 3.4x1038 |

double | Float | 8 | 64 | -2.2x10308 | 2.2x10308 |

boolean | Boolean | 1* | 8* | false | true |

char | Character | 2 | 16 | Unicode | Unicode |

* The size of boolean variables is dependent on the virtual machine that executes the code. Typically, the most conservative size of one byte is used.

Table 1 shows all eight of the primitive data types available in Java. The first column shows the keywords we use in Java when we declare variables (we will look at declaring variables shortly).

The Type column shows the fundamental data type of each primitive. There are only two data types: Integer and Floating Point. Integer data types are whole numbers—they can be negative and positive—but they cannot have any decimal part: e.g., 6, 2378, or -1772. Floating-point data types are used to represent values with some fractional part, such as 28.7 or -1772.1671.

The Boolean and Character types are actually integers, but there are various functions available in Java that treat these particular primitives differently than regular integers. For instance, when we print the value of a boolean variable, we will get true or false printed to the screen instead of 1 or 0 (even though the underlying data is literally an integer where 0 means false and anything else means true). And, when we print the value of a char variable, Java will print out the Unicode symbol that corresponds to the integer value of the char variable.

The third column shows the sizes in bytes for each of the primitive data types. Figure 36 shows an illustration of the sizes of each primitive. Each box represents one byte of RAM. The numbers show the most common byte order—Java is Little Endian, the lowest byte in a multiple-byte data type, on the right side. Floats and doubles use a specific format that is very different from integers. The format of floats and doubles in Java follows the IEEE 754 Standard, which is a scientific notation for representing approximations to fractions in binary.

Figure 36: Primitive Data Type Sizes

The fourth column shows how many bits (binary digits) each primitive takes up in RAM. This will always be a multiple of eight because RAM is a series of bytes, and bytes are eight bits each. The exact workings of binary are not important at this point (we will look in some detail at binary when we look at the bitwise operators), but it is easy to represent any number in binary that you can represent in base 10. For instance, the number 219 in base 10 is the same as 11011011 in binary.

The final two columns show the available ranges of the primitives—the minimum and maximum values that variables of each primitive can store.

Programmers should become familiar with all eight of the primitive data types, but in practice we tend to use some types more than others. Most programmers will use int for all numerical, whole-number variables. The smaller integer data types, byte and short, are used to save space in RAM when the range of values being stored is known to fall within the much smaller range of the byte or short. Similarly, the long data type is not typically used unless the programmer has a specific reason to do so—for instance, if the programmer needs to store values greater than 2.15 billion.

Note: If you require more range than a long can accommodate, there is a standard class called “BigInteger” that offers arbitrarily large integers. BigInteger is not a primitive, but instead a class built of primitives that allows computation with very large values (used in encryption algorithms, for example). This range of computation comes at a cost, and BigInteger computations are much slower for the JVM to perform than computations with int or long. In order to use a BigInteger, we need to import java.math.BigInteger and declare a BigInteger object.

Programmers often use double as the default data type when they need to represent floating-point values. A double is twice as large as a float (64 bits for doubles, 32 for floats), which means that if you have a lot of variables (such as an array with one million elements), storing the elements as float will mean the array takes roughly four megabytes of RAM rather than eight. The downside to float is that it is far less accurate. The extra accuracy offered by doubles can be very important because every operation we perform on floating-point variables (double and float) has the potential to introduce and magnify rounding errors.

The boolean type has only two possible states—true and false. We use boolean variables when we know there are only two states to a variable, and the states need not necessarily be true and false. For instance, a boolean variable could represent a person’s gender, a light switch being on or off, or the digits 0 and 1. And boolean values are commonly used to create conditional, or logical, expressions. We often use a logical expression without actually defining a variable, but behind the scenes a boolean variable is being created and evaluated for every logical expression that is executed (we will see many logical and conditional expressions in the section on control structures).

The char data type is used to store letters, digits, punctuation, and many other symbols (char represents characters using the Unicode encoding scheme). The char data type is really just a short, but the JVM treats the 16 bits differently. For example, if you set a short to 65 and print the results using a println, you will see 65. But if you use a char variable, set it to 65 and print the results with a println the program will print A. This is because the println function is designed to treat char data types as references to Unicode characters. The symbol in the Unicode table at position 65 is A, therefore println prints A to the screen instead of 65 when it sees that the data type is char.

char variable data types are strung together to form strings of characters. Strings are simply text, they are not a primitive type, and we will cover them in a moment.

Note: The primitive data types always have the same size, regardless of the value they store. All int variables consume four bytes, regardless of the value they store. For example, the number 3 could theoretically be stored using only two bits, 11, in binary. But, if we store 3 in an integer, it will be padded with many zeros to take up the remaining bits of the int: 00000000 00000000 00000000 00000011.

Variables

A variable is a named, primitive data type. Each variable is a collection of bytes acting as one of the primitive data types from Table 1, and which we have given a name. We refer to variables by their name (instead of their addresses in RAM) and can read or change their values of RAM using the variable names as our references. A variable stores information, such as the number 3 or the name Jane Smith.

Variable declaration and definition

To declare a variable is to state that it exists. We give the variable a data type and a name—that is, an identifier. To define a variable is to specify a value for it. Variables must be declared and defined before they are used.

Initialization comes when we define a variable’s value for the first time. A variable that is declared but not defined is called uninitialized, and the variable cannot be used in computation until it is initialized. In Java, we can declare and initialize a variable in a single line of code using the assignment operator “=” (see the section on operators for more information on the assignment operator).

Code Listing 5.0 shows various declarations and definitions of variables.

Code Listing 5.0: Declaring and Defining Variables

public class MainClass { public static void main(String[] args) { int i = 100; // Declare and initialize an int. int b = 10, c = 5;// Declare and initialize two variables. boolean mb = false;// Declare and define a Boolean. char myLetter; // Declare a character. myLetter = 'h'; // Define/set the character to be 'h'. byte hp, bp, sp; // Declare 3 byte variables. hp = bp = sp = 0; // Set all 3 bytes to 0. short ss = 189; // Declare and define a short integer. long p = ss; // Declare and define a long with the value of ss. double myDouble = 100.0;// Declare and define a double. float f = 0.1f; // Declare and define a float. } } |

When declaring a variable, the data type comes first, followed by the name of the variable, and optionally followed by the initial setting for the variable. Variables can be defined on the same line as the declaration (such as the int variables a, b, and c in Code Listing 5.0) or on a separate line (such as the char variable myLetter in Code Listing 5.0). You can declare and define more than one variable of the same type by separating each variable with a comma (as shown by the variables b and c in Code Listing 5.0).

The numbers in Code Listing 5.0, such as 189 and 0.1f, as well as the character 'h' and the boolean value false, are called literals. We will examine the literals later.

You can also use mathematical and logical statements to initialize a variable. For example: int someInteger = 100*9+1. This will set the variable someInteger to 901.

Tip: Name your variables so that their purposes are obvious. Carefully selecting names for variables can greatly increase the readability of code. In general, a programmer should name variables succinctly. Consider “s” as a variable to store an employee's salary vs. the more appropriately named “employeeSalary.” Calling the variable “employeeSalary” is much more descriptive than the letter “s.”

Note: As mentioned, many programmers use a technique called Camel Case to name identifiers when programming with Java (and other languages). The first word of a member method or variable's name is lowercase, and all subsequent words begin with an uppercase letter. For example, “myVariable” and “vehiclesPerHour.” But class names begin with an uppercase letter—“MyClass” and “UserInformation.”

Detour: strings

Before we move to describing literals, let’s take a brief detour to examine a data type that is not a primitive. String is not a primitive, but it is so commonly used that it can be introduced with the other data types. A String is an array (see the section on arrays) or sequence of char variables, one after the other. A String can be used to represent text, numbers, or sequences of Unicode symbols (a String is literally a string of char variables). We surround text with double quotes to indicate that it is a String.

String str = "This is a string variable!";

We can define a String on multiple lines by using the + operator to connect more than one String together (Code Listing 5.1).

Code Listing 5.1: Multiple-Line String

String description = "Strings can " + "be defined on multiple " + "lines with the + operator!"; |

There is a very important distinction to make between a String and numerical data types such as int and float. A String is not interchangeable with a numerical data type, even if both have the same value. A String can be parsed into integers using a function call, Integer.parseInt, but it is not possible to assign a String to an integer in the normal way. The second line of Code Listing 5.2 is illegal:

Code Listing 5.2: Strings and Numerical Data Types are Not Interchangeable

String str = "100"; int j = 10 + str; |

A String is an array of characters, and each character has a more or less arbitrary numerical value (it is the Unicode character set). If we add 10 to the character 7, we do not get 17, but 65! This is because the character 7 is not equal to the integer 7. The character 7 has a Unicode value of 55. For this reason, we are not able to convert a numerical string such as 1278 to the integer 1278 without calling a helper function such as Integer.parseInt.

Code Listing 5.3 shows parsing a String to an int and adding a character to an integer so that these operations will give the normal, expected results. We will cover calling functions, boxing/unboxing, and the Integer class later. Let it suffice to say that Integer.parseInt(str) will return the int 7, the numerical value of the characters of the String.

Code Listing 5.3: Parsing Strings and Characters

public class MainClass { public static void main(String[] args) { // Set str to the string "7". String str = "7";

// Set j to the integer 10 + "7" parsed to int. int j = 10 + Integer.parseInt(str);

// Set c to the character '7'. char c = '7';

// Set i to 10 + 7, notice we subtract the // character '0' from '7' to get the int 7 // from the character '7' instead of parsing.

int i = 10 + c - '0'; // Both j and i are set to 17. System.out.println("j: " + j); System.out.println("i: " + i); } } |

Code Listing 5.4 shows an example of adding an integer to a String.

Code Listing 5.4: Adding Integers to Strings

int idNumber = 26771; String desc = "The ID number is " + idNumber + "."; |

In Code Listing 5.4, we use the concatenation operator, +, to place the value 26771 in the middle of a String. Java will create the value “The ID number is 26771” and store this in the String desc. It is important to note that the integer idNumber has been converted to a normal decimal string automatically.

Casting

To cast in Java means to change the value of a variable or literal to that of another primitive data type. To cast from one type to another, we use the primitive we want to cast to in brackets. Code Listing 5.5 shows some examples of casting numerical data types.

Code Listing 5.5: Casting

int i = (int) 7.8; // Cast the double 7.8 to an integer, store in i double d = (double) 89.7f;// Cast the float 89.7f to a double, store in d short q = (short) (i * d);// Cast the double i*d to a short and store in q |

Casting a floating-point value to an integer type results in truncation, so that 7.8 becomes 7 when stored in the integer i.

This example shows something else interesting. The expression (i*d) results in a double. When we perform an operation and mix integers and doubles, or floats, the integers will be temporarily changed to double or float. That is, integers are implicitly cast to double temporarily when performing mixed arithmetic.

Note: Each of the fundamental data types also has an object version with a similar name: Integer, Double, Short, etc. All are classes used to wrap the fundamental data types. The classes contain useful static methods that can be used for parsing strings to integers or doubles. Changing a fundamental data type to its class version (e.g., int to an Integer) is called Boxing. Changing a boxed Integer back into a primitive int is called Unboxing. For more information on Boxing and Unboxing, visit Oracle at https://docs.oracle.com/javase/tutorial/java/data/autoboxing.html.

Literals

A literal is a value written in the code, such as 27, the character A, or the floating-point value 78.19f. We have seen many literals already. We often set the values of variables to literals or use literals in computations in order to produce some result, then store it in a variable.

Integer literals

Integer literals are simply whole numbers. Integers can be positive or negative. Negative integer literals have the minus sign to the left of the left-most digit (e.g., -27). For positive integer literals, the plus sign, +, is optional and almost never used (i.e. it would be more normal to use 78 rather than +78, but both are legal).

Code Listing 5.6: Integer Literals

int i = 100; int j = -239; short p = 99; byte q = -55; long l = 6787612356765l; int h = 0x5DD2; // Hexadecimal int w = 067; // Octal int bin = 0b10011001; // Binary literal, Java SE 7 and above |

Code Listing 5.6 shows a code snippet with several integer variables declared and defined using integer literals. The literals are on the right side of the assignment operator: =. A simple integer literal is an unadorned whole number such as the 100, -239, 99, and -55 in Code Listing 5.6. Such literals are interpreted by the JVM as being normal decimal numbers, and they are converted to binary behind the scenes.

Long literals have an “l” appended to the end (note that this is a lowercase L), as the line “long l = 6787612356765l;” shows. You can use a regular int literal to set the value of a long integer, but only if the literal does not fall outside the range of an int. Java will automatically convert the int literal to a long literal to store in the variable when the variable is of type long. If the literal is too large for a standard int to hold, it must have the “l” suffix.

Typically, programmers use base 10 when specifying integer literals. Literals without extra prefixes are assumed to be in base 10 (such as 100, -239, and 99 in Code Listing 5.6) because this is the most common counting system. The final three literals illustrated in Code Listing 5.6 show how to define integer literals using the hexadecimal (base 16), octal (base 8), and binary (base 2) counting systems. Sometimes it is easier to use hexadecimal or octal because these counting systems match the binary system that the computer uses more closely than does base 10. In order to define a hexadecimal integer, you begin the literal with 0x. In order to define an octal literal, we use a leading zero. This can be quite confusing, so it pays to be very careful when reading literals in more advanced code—the number 067 is not 67 in decimal, it is 55.

The final example in Code Listing 5.6 is a binary literal. Binary literals are only provided in Java SE 7 (released in 2011) and above. They allow us to express an integer by directly specifying its bits. In order to use a binary literal, begin the literal with the 0b prefix. The literal 0b10011001 means 153 in base 10. The binary string in Code Listing 5.6 has only eight bits, but it could consist of up to 32 bits. I have used this literal to set the value of the variable bin, the remaining bits on the left of the eight bit will be filled with 0. The entire value of the bin variable will be 00000000 00000000 00000000 10011001.

Floating-point literals

A floating-point number is a number whose decimal point can move, such as 15.6 becoming 1.56. This is fundamentally different from an integer, which does not have a decimal point. Floating-point literals have two primitive types—float and double. When using float literals, we place “f” on the end of the literal. You’ll see that double literals are unadorned, but they should always have a decimal point (i.e. instead of 6, we would write 6.0 in order to show that the 6 is not an integer but a double). Code Listing 5.7 shows some examples of floating-point literals being used to initialize float and double variables.

Code Listing 5.7: Floating-Point Literals

float y = 99.0f; float q = -3.4512f; double h = 99.0; double g = -3.4512; double p = 2.4e3; double u = 2.4e-3; |

The final two examples in Code Listing 5.7 use scientific notation. When we use 2.4e3, what we mean is 2.4x103 (or 2.4 by 10 to the power of 3). Likewise, 2.4e-3 means 2.4x10-3 or 0.0024.

You must be aware that float and double types rarely store the values we actually specify. Although perhaps a little strange, there is no IEEE 754 float for the value 1/3, or for 3/5. The format simply does not include a representation for these simple fractions. When we set a float or double to 1/3, we are really setting it close to 1/3. See the section on floating-point arithmetic for more details, and always keep in mind that float and double types are merely approximations of the values we specify.

Boolean and character literals

Code Listing 5.8: Boolean and Character Literals

boolean b1 = true; boolean b2 = false; char m = 'h'; char g = 65; // 65 is 'A' in Unicode! char c = 0b1000001; // 65 in binary, this is also the character 'A'. |

Code Listing 5.8 shows some examples of boolean and char literals. There are only two boolean literals—true and false. Character literals are almost always surrounded by single quotes such as'h', but it is possible to use an integer literal to set a character (look up the Unicode character chart at http://www.unicode-table.com/en/ for a table of the Unicode characters and their corresponding integer values, and note that the table is laid out in hexadecimal).

Note: As with the integer literals, it is perfectly valid to express the value of a char in hexadecimal, octal, or binary. But this is very rare, and, typically, if we need to dictate the value of a variable using numerical digits, we should use a short instead of a char.

String literals

String literals are surrounded by double quotes, as opposed to single quotes used for char literals. You can continue long string literals by splitting them onto separate lines using the “+” operator (this is called concatenation of String literals, as we will see in the following chapter). Code Listing 5.9 shows examples of String literals.

Code Listing 5.9: String Literals

String m = "This is a string literal"; String j = "If your string literal is too long, you can " + "use the + operator and continue on the next line!"; |

Detour: arrays

An array is a collection of items in which all items are of the same data type. For instance, a collection of 10 ints or a collection of 1,000 doubles. Arrays can be created to store collections of user types, too, such as classes and enumerations. (We do not cover enum in this book, but it is a special type of class designed to store a series of constants.) The elements of an array are numbered starting with 0. We can use the array's name along with an index in square brackets, [ and ], in order to specify to which element we wish to read or write.

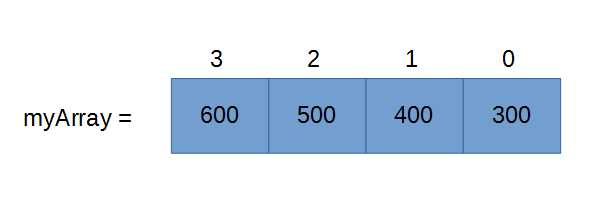

Figure 37: Array of Integers

Figure 37 shows an array of four integers called myArray. Each element in the array is represented by a box with two numbers. The number inside the box is the value of the element, and the number outside the box is the index of the element within the array. Notice that the first box (the one on the right) has an index of 0, not 1. And the final box (on the left) has an index of 3 instead of 4. This is extremely important, and it may take some getting used to—Java counts from 0, not 1. So, if we create an array with 10 integers, the elements will be numbered from 0 to 9. There are still 10 items in the array—0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9, but they are not numbered in counting order.

Code Listing 5.10: Declaring and Defining an Array

public class MainClass { public static void main(String[] args) { int[] myArray = new int[4]; myArray[0] = 300; myArray[1] = 400; myArray[2] = 500; myArray[3] = 600; System.out.println("Element 0 is: " + myArray[0]); System.out.println("Element 3 is: " + myArray[10-7]); } } |

Code Listing 5.10 shows an example of how we might set up the array illustrated in Figure 37. The declaration of the array is int[] myArray = new int[4];. Notice the [] beside the data type. These brackets next to a data type declaration mean we do not want a single integer but rather an array to be declared. Then, after the name of the array, myArray, we use the assignment operator and the new keyword to specify how many elements the array should hold. The new keyword is also used to construct objects, as we will see. Code Listing 5.10 also shows how we set the individual elements of the array. We use the array's name, myArray, followed by the index of the element in square brackets [ and ].

When we want to read the values of the elements of an array, we use the square brackets again, as illustrated by the System.out.println calls in Code Listing 5.10. Note that in the second println, we use an expression in the square brackets, [10-7], instead of a simple integer. We can use any expression we like in the square brackets to index array elements, but the expression must be integer—we cannot reference the element at position 2.5 because all elements in an array have whole number indices (we will cover arithmetic expressions in some detail later). This means we are able to index array elements with variables, too, such as myArray[i], in which i might be an integer variable.

We must be very careful to ensure that we never index outside the bounds of an array. The array in Code Listing 5.10 has four elements numbered 0, 1, 2, and 3. We cannot index array element myArray[-15] or myArray[4] or myArray[2367] because these elements do not exist. Indexing outside the bounds of an array is relatively safe in Java compared to languages such as C, but it will cause an exception to be thrown that can possibly crash the application.

Code Listing 5.11: Array Initialization Syntax

public class MainClass { public static void main(String[] args) { int[] myArray = { 300, 400, 500, 600 }; System.out.println("Element 0 is: " + myArray[0]); System.out.println("Element 3 is: " + myArray[10-123]); } } |

Code Listing 5.11 shows the same array as Code Listing 5.10, but here we use a different syntax to set the values of the array. This is called array initialization. We follow the name of the array with the assignment operator, then a comma-separated list of elements between curly braces { and }. When we initialize an array using this syntax, we do not need to specify the size of the array because the compiler can infer the size from the number of elements we use in the curly braces.

Multidimensional arrays

A multidimensional array is a collection of items that are accessed using more than one index. For example, a grid of 10x50 integers or a 3-D box filled with 7x9x10 Boolean values. The basic arrays we have examined use one index in order to access any item, but grids and blocks of variables can be collected into multidimensional arrays. The number of dimensions in an array specifies how many indices we need in order to exactly reference any one element. For instance, a three-dimensional array requires three indices, one for each dimension, while a 2-D array requires two indices, and a 12-dimensional array requires 12 indices, etc.

Note: As the number of dimensions of an array increases, the amount of memory required to store the array increases dramatically. For instance, a 2-D array of bytes with dimensions 5x7 requires 5*7 bytes to store. However, a 3-D array with dimensions 5x7x8 requires 5*7*8 bytes to store. For this reason, we don’t often see multidimensional arrays with dimensions numbering three or four.

Tip: Do not try to envisage what higher dimensional arrays look like (4-D, 5-D, etc.). Multidimensional arrays can be confusing to imagine. We live in a 3-D world, so it’s easy to imagine a 2-D grid or a 3-D box full of array elements. However, it is difficult to envisage what a 4-D or a 5-D array of elements looks like. It really doesn’t matter what the array would look like, though. All we care about is reading and writing the elements. It is no more difficult to read/write an element in a 2-D array than it is to read/write an element in a 12-D array. With 2-D we would use two indices, and for 12-D we would use 12 indices.

Code Listing 5.12: Declaring and Defining a 2-D Array

public class MainClass { public static void main(String[] args) { float[][] array2d = new float[7][5]; array2d[0][0] = 50.5f; array2d[4][4] = 60.5f; array2d[3][1] = 10.3f; System.out.println("Element (3, 1): " + array2d[3][1]); System.out.println("Element (4, 0): " + array2d[4][0]); } } |

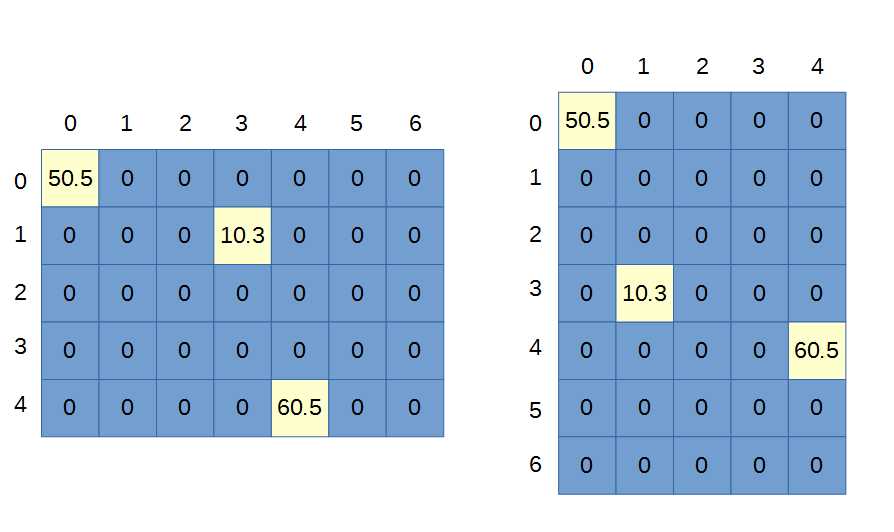

Code Listing 5.12 shows how to declare a 2-D array of float types. We use the data type float[][] to signify that we wish to declare an array with two indices per element. The name of the array, array2d, is followed by the assignment operator and the new keyword. Then we supply the number of elements in each dimension of the array, 7 and 5. This means we are creating a grid of 7x5 floating-point values. Figure 38 shows two ways we might illustrate this array.

Figure 38: 2-D Array

Figure 38 shows two depictions of the same array defined in Code Listing 5.12. With a 2-D array, we are essentially representing rows and columns, but the orientation is up to the programmer. The trick to properly manipulating 2-D arrays is to envisage the array in the same orientation each time. The important thing is not the orientation of the grid but the fact that it has 7x5 elements. We can view this grid as having seven columns and five rows (the illustration on the left in Figure 38), or we can view the grid as having seven rows and five columns (as depicted in the illustration on the right of Figure 38). It does not matter which method (and indeed there are more orientations for a 2-D array than these two!) we use to illustrate a 2-D array, the important fact is that there are seven indices in the first index of the array and five in the second.

Note: In Java, when we declare an array, the values of the elements are initialized to 0 for integer data types, 0.0 or 0.0f for floating-point types, and false for Boolean.

Let’s next look at for loops. My objective here is to demonstrate how to correctly traverse (run through every element of) a 2-D array, rather than to explain the syntax of the loop itself.

Code Listing 5.13: Using Nested For Loops to Traverse a 2-D Array

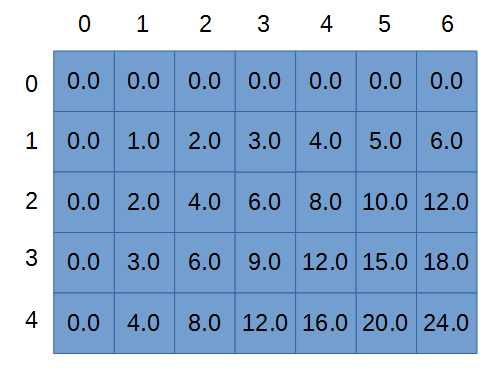

public class MainClass { public static void main(String[] args) { float[][] array2d = new float[7][5]; for(int y = 0; y < 5; y++) { for(int x = 0; x < 7; x++) { array2d[x][y] = x * y; } } } } |

Code Listing 5.13 shows how to traverse an entire 2-D array. It uses nested for loops, the outer for loop counts from 0 up to 5 (i.e. 0, 1, 2, 3, 4). Each time this counter (y in the code) is incremented, another counter, x, runs from 0 up to 7 (i.e. 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6). Thus, the inner body of these two nested for loops will run 7x5 times, and each time, the x and y iterators will be able to access a different element of the 7x5 array. In the body of the loop, we set the elements of the array as the product of their indices. Figure 39 shows the result in the pattern in the array after these loops are executed.

Figure 39: 2-D Array after For Loops

2-D arrays are usually one of the most daunting aspects of Java for new programmers. However, I hope to illustrate that there is nothing difficult about these data structures at all—it’s only a matter of getting the indices in the right order every time. The final example in this chapter shows how to declare and traverse a 4-D array, setting every element in the entire array to 1729 with a few nested for loops (again, we will cover for loops in more detail in the control structures section, and it would be a very good idea to read that chapter and return to this example).

Code Listing 5.14: Creating and Traversing a 4-D Array

public class MainClass { public static void main(String[] args) { // Declare 4-D array. int[][][][] arr4D = new int[3][4][5][6]; // Set all the elements to 1729. for(int a = 0; a < 3; a++) { for(int b = 0; b < 4; b++) { for(int c = 0; c < 5; c++) { for(int d = 0; d < 6; d++) { arr4D[a][b][c][d] = 1729; } } } } } } |

It is impossible to imagine what 4-D shapes look like. We cannot draw the array from Code Listing 5.14 on a piece of paper. And yet, manipulating and traversing the shape is as easy as 3.14159. All that matters is that the array has four dimensions with sizes 3, 4, 5, and 6, respectively. And, when we want to traverse the entire array, we can nest four for loops, each counting up to 3, 4, 5, and 6. We could set a single element with a statement such as arr4D[1][3][2][5] = 87539319;. But we must be careful that none of our indices goes outside the bounds for the particular dimension it references.

Also, the order in which we nest the for loops does not matter. The a counter happens to be on the outside loop in Code Listing 5.14, but we might have placed this for loop as the innermost one. The only important thing is that the counter is counting 0, 1, and 2, and we are using it to access a dimension that has elements indexed 0, 1, and 2.

- 1800+ high-performance UI components.

- Includes popular controls such as Grid, Chart, Scheduler, and more.

- 24x5 unlimited support by developers.