CHAPTER 2

Service Mesh and Istio

Organizations all over the world are in love with microservices. Teams that adopt microservices have the flexibility to choose their tools and languages, and they can iterate designs and scale quickly. However, as the number of services continues to grow, organizations face challenges that can be broadly classified into two categories:

- Orchestrate the infrastructure that the microservices are deployed on.

- Consistently implement the best practices of service-to-service communication across microservices.

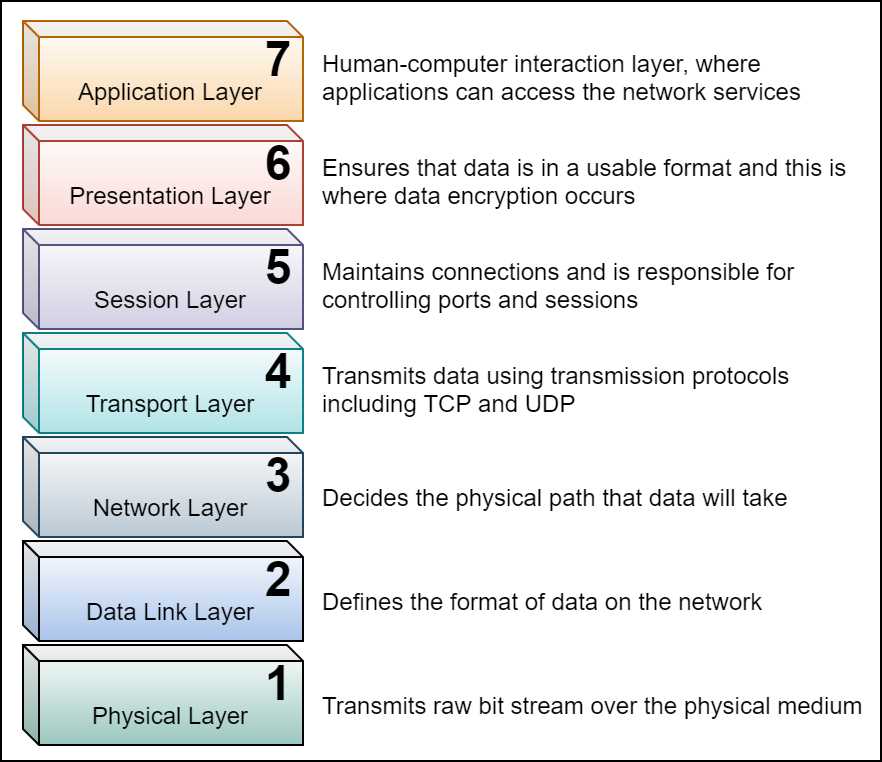

By adopting container orchestration solutions such as Docker Swarm, Kubernetes, and Marathon, developers gain the ability to delegate infrastructure-centric concerns to the platform. With capabilities such as cluster management, scheduling, service discovery, application state maintenance, and host monitoring, the container orchestration platforms specialize in servicing layers 1–4 of the Open Systems Interconnection (OSI) network stack.

Figure 1: OSI stack (source)

Almost all popular container orchestrators also provide some application life-cycle management (ALM) capabilities at layers 5–7, such as application deployment, application health monitoring, and secret management. However, often these capabilities are not enough to meet all the application-level concerns, such as rate-limiting and authentication.

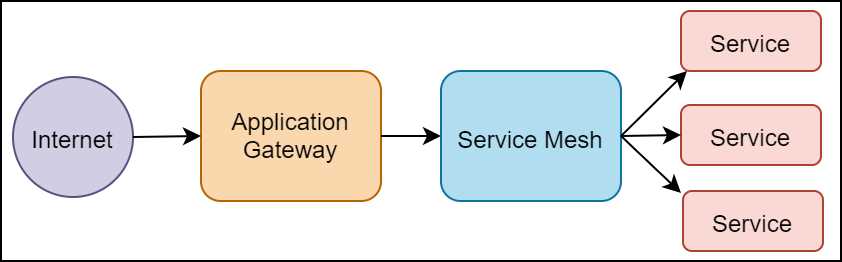

Application gateways such as Ambassador, Kong, and Traefik solve some of the service-to-service communication concerns. However, application gateways are predominantly concerned with managing the traffic that passes through the data center to network infrastructure, also known as north-south network traffic. Application gateways lack the capabilities to manage the communication between microservices within the network, also known as east-west network traffic. Thus, application gateways complement (but do not replace the need for a solution that can manage) the service-to-service communication. Figure 2 is a high-level design diagram that presents where application gateways fit within the architecture of a system.

Figure 2: Application gateway and service mesh

Finally, in an unrealistically utopian scenario, an organization can enforce all the individual microservices to implement standard service-to-service communication concerns such as service discovery, circuit breaking, and rate-limiting. However, such a solution immediately starts facing issues with enforcement of consistency. Different microservices, constrained by variables such as programming language, availability of off-the-shelf packages, and developer proficiency, implement the same features differently. Even if the organization succeeds in implementing this strategy, maintaining the services, and repeated investments required to keep the policies up to date, become a significant challenge.

Service mesh

Due to these issues, there is a need for a platform-native component that can take care of network-related concerns so that application developers can focus on building features that deliver business value. The service mesh is a dedicated layer for managing service-to-service communication and mostly manages layer 5 through layer 1 of the OSI network stack. The service mesh provides a policy-based services-first network that addresses east-west (service-to-service) networking concerns such as security, resiliency, observability, and control, so that services can communicate with each other while offloading the network-related concerns to the platform. The value of using service meshes with microservices scales linearly with the number of microservices. The higher the number of microservices, the more value organizations can reap from it.

Note: The service mesh is named so because of the physical network topology that it uses to operate in a cluster. Each node in a mesh topology is connected directly to several other nodes. A mesh network generally configures itself and dynamically distributes the workload. The mesh is, therefore, the design of choice for service mesh.

Following are some of the key responsibilities that a service mesh offloads from microservices:

- Observability: The ability to extract metrics from executing services without instrumenting the services themselves. Service meshes provide consistent metrics across all the services that make up the application, so that developers can trace every operation as it flows across services. In service meshes, the capability to collect traces and metrics is independent of the metrics backend provider. Therefore, organizations can choose the metrics backend according to their needs. Observability is composed of the following three features:

- Logging: The service mesh enforces baseline visibility of operations to all microservices. What this means is that even if a microservice does not log anything, the service mesh records information such as source and destination, request protocol, response, and response status code.

- Metrics: Without any instrumentation, the service mesh emits telemetry such as overall request volume, success rate, and source. This information is useful for automating operations such as autoscaling.

- Tracing: Tracing helps track operations across services and dependencies. To enable tracing, microservices are required to forward context headers, and the rest of the configuration, such as the generation of span IDs, is handled by the service mesh. Traces are used to visualize information such as dependencies, request volume, and failure rates.

- Traffic control: There are three key traffic control features that are required by microservices and provided by service meshes. The first feature is traffic splitting based on information available at layer 7, such as cookies and session identifiers. Applications usually use this feature for A/B testing to validate a new release. The second key feature in this category is traffic steering, with which a service mesh can look into the contents of a request and route it to a specific set of instances of a microservice. Finally, microservices can use a service mesh gateway to apply access rules, such as a whitelist or blacklist created by the administrator to route the ingress (incoming) and egress (outgoing) traffic.

- Resiliency: To counter an unstable network, microservices are required to implement resiliency measures such as timeouts and retries when trying to access out-of-process resources and other microservices. In addition to automatic retries, service meshes support some of the common resiliency design patterns such as circuit breaker, health checks, and many others, which help microservices gain control over the chaotic network that they operate.

- Efficiency: Service meshes do not significantly degrade the performance of applications in return for the flexibility they offer. One of the primary goals of service meshes is to apply a minimal resource overhead and scale flexibly with microservices.

- Security: For service meshes, security includes three distinct capabilities. The first one is authentication. Service meshes support several authentication options such as mTLS, JWT validation, and even a combination of the two. Service meshes also provide service-to-service and user-to-service authorization capabilities. The two types of authorizations that are supported by service meshes are role-based access control (RBAC) and attribute-based access control (ABAC). We will discuss these policies later in this book. Finally, service meshes can enforce a zero-trust network by assigning trust based on identity as well as context and circumstances. With service meshes, you can enforce policies such as mTLS, RBAC, and certificate rotation, which help create a zero-trust network.

- Policy: Microservices require enforcement of policies such as rate limiting and access restrictions, among others, for addressing security and non-functional requirements. Service meshes allow you to configure custom policies to enforce rules at runtimes such as rate limiting, denials, and whitelists to restrict access to service, header rewrites, and redirects.

The service mesh helps decouple operational concerns from development so that both the operations and development teams can iterate independently. For example, with a service mesh managing the session layer (layer 5) of the microservice hosting platform, operations need not depend on developers to apply a consistent resiliency strategy such as retries on all microservices. As another example, customer teams do not need to depend on the development or operations team to enforce quotas based on pricing plans. For organizations that depend on many microservices for their operations, the service mesh is a vital component that helps them compose microservices and allow their various teams, such as development, operations, and customer teams, to work independently of each other.

Istio is one of the open-source implementations of a service mesh. It was initially built by Lyft, Google, and IBM, but it is now supported and developed by organizations such as Red Hat, and many individual contributors from the community. Istio offloads horizontal concerns of applications such as security, policy management, and observability to the platform. Istio addresses the application-networking concerns through a proxy that lives outside the application. This approach helps applications that use Istio stay unaware of its presence, and thus requires little to no modification to existing code. Although Istio works best for microservices or SOA architectures, it helps organizations that have several legacy applications reap its benefits because of its nature of operating out of band (sidecar pattern) from the underlying application.

Note: Many open-source projects within the Kubernetes ecosystem have nautical Greek terms as names. Kubernetes is the Greek name for “helmsman.” Istio is a Greek term that means “sail.”

Another popular service mesh available today is Linkerd (pronounced linker-dee), which is different from Istio in that its data plane (responsible for translating, forwarding, and observing every network packet that flows to and from a service instance) and control plane (responsible for providing policy and configuration for all of the running data planes in the mesh) are included in a single package. It is an open-source service written in Scala, and it supports services running in container orchestrators like Kubernetes as well as virtual and physical machines. Both Istio and Linkerd share the same model of data plane deployment known as the sidecar pattern. Let’s discuss the pattern in detail.

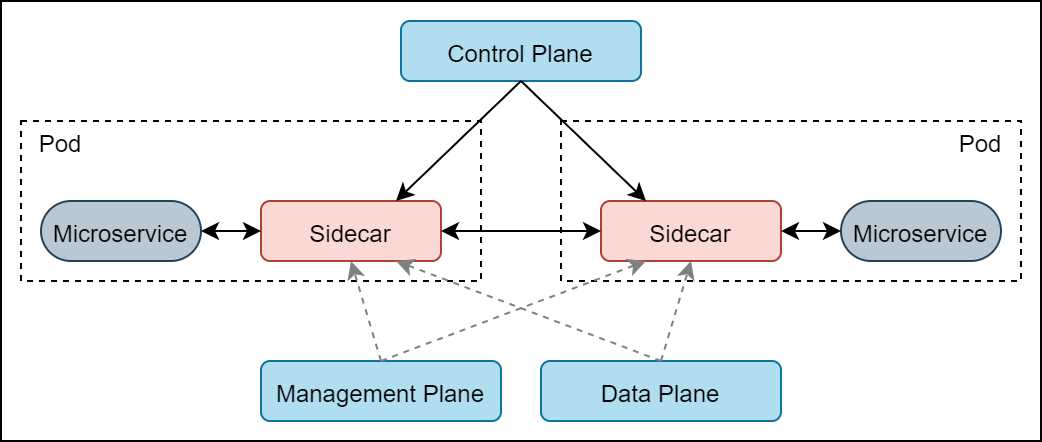

Sidecar

Let us briefly discuss the sidecar pattern, since this pattern is the deployment model used in Istio to intercept the traffic coming in or going out of services on the mesh. A sidecar is a component that is co-located with the primary application, but runs in its own process or container, providing a network interface to connect to it. While the core business functionalities are driven from the main application, the other common crosscutting features, such as network policies, are facilitated from the sidecar. Usually, all the inbound and outbound communication of the application with other applications takes place through the sidecar proxy. The service mesh proxy is always deployed as a sidecar to the services on the mesh. By introducing service mesh, the communication between the various services on the mesh happens via the service mesh proxy.

Figure 3: Sidecar pattern in service mesh

As evident from the previous diagram, all inbound (ingress) and outbound (egress) traffic of a given service goes through the service mesh proxy. Since the proxy is responsible for application-level network functions such as circuit breaking, the microservice is limited to primitive network functions such as invoking an HTTP service.

Service mesh architecture

Since Istio is an implementation of the service mesh, we will first discuss the architecture of the service mesh and then discuss how the components of Istio fill it up.

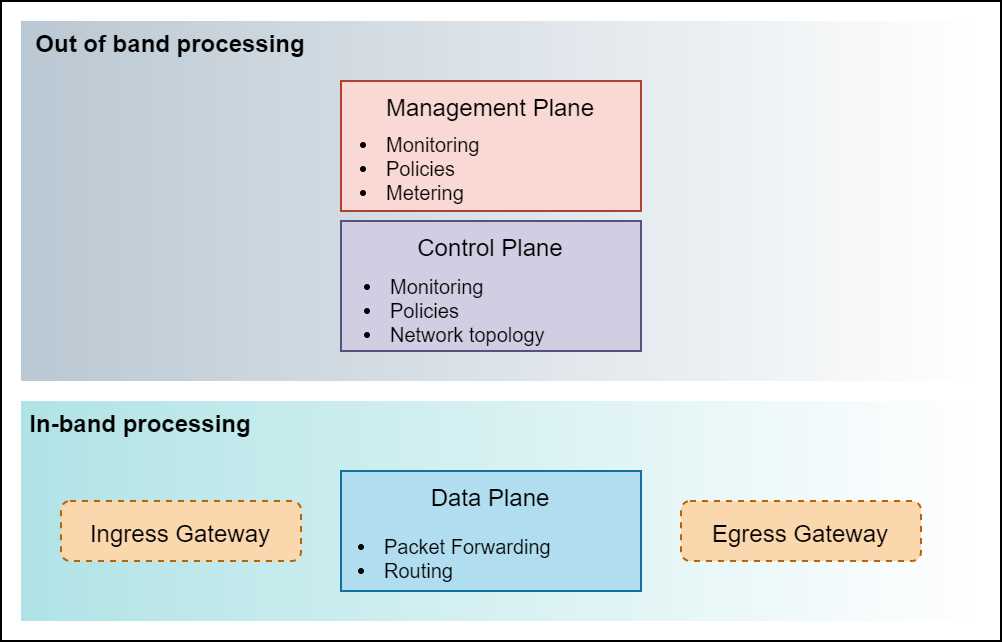

Since the concept of a service mesh is derived from physical network topologies, it is necessary to understand the concept of planes in networking. The following are the three planes or areas of operations in a software defined network (SDN) in increasing order of proximity to data packets being transmitted in the network:

- Data plane: Functions or processes that receive, parse, and forward network packets from one interface to another.

- Control plane: Functions or processes that determine the path that network packets use. This plane understands the various routing protocols such as spanning tree and LDP which it uses to update the routing table used by the data plane.

- Management plane: Functions or processes that control and monitor the device and hence, the control plane. In networking, this plane employs protocols such as SNMP to manage devices.

The concept of network plane components of layer 4 when applied to layer 5 and above form the concepts of a service mesh. There are over a dozen service mesh implementations; however, all implementations broadly consist of the same three planes that we previously discussed. Some service meshes such as Istio combine the management and control planes in the control plane.

Figure 4: Service mesh planes

In a service mesh, the three planes play the following roles:

- Data plane: This component intercepts all traffic of all the requests that are sent to the applications on the mesh. It is also responsible for low-level application services such as service discovery, health checks, and routing. It manages load balancing, authentication, and authorization for the requests that are sent to the application. This plane collects metrics such as performance, scalability, security, and availability. This is the only component that touches the packets or requests on the data path.

- Control plane: This component monitors, configures, manages, and maintains the data planes. It provides policies and configurations to data planes, and thus converts the data planes deployed as isolated stateless sidecar proxies on the cluster to a service mesh.

- Management plane: This component extends the features of the system by providing capabilities such as monitoring and backend system integration. It enhances the control planes by adding support for continuous monitoring of policies and configurations applied by the control plane for ensuring compliance.

In addition to the three planes, a service mesh supports two types of gateways that operate at the edge of the service mesh. The ingress gateway is responsible for guarding and controlling access to services on the mesh. You can configure the ingress gateway to allow only a specific type of traffic such as SFTP on port 115, which blocks incoming traffic on any other port and of any other type. Similarly, the egress gateway is responsible for routing the traffic out of the mesh. The egress gateway helps you control the external services to which the service on the mesh can connect. Apart from security, this also helps operators monitor and control the outbound network traffic that originates from the mesh.

Istio architecture

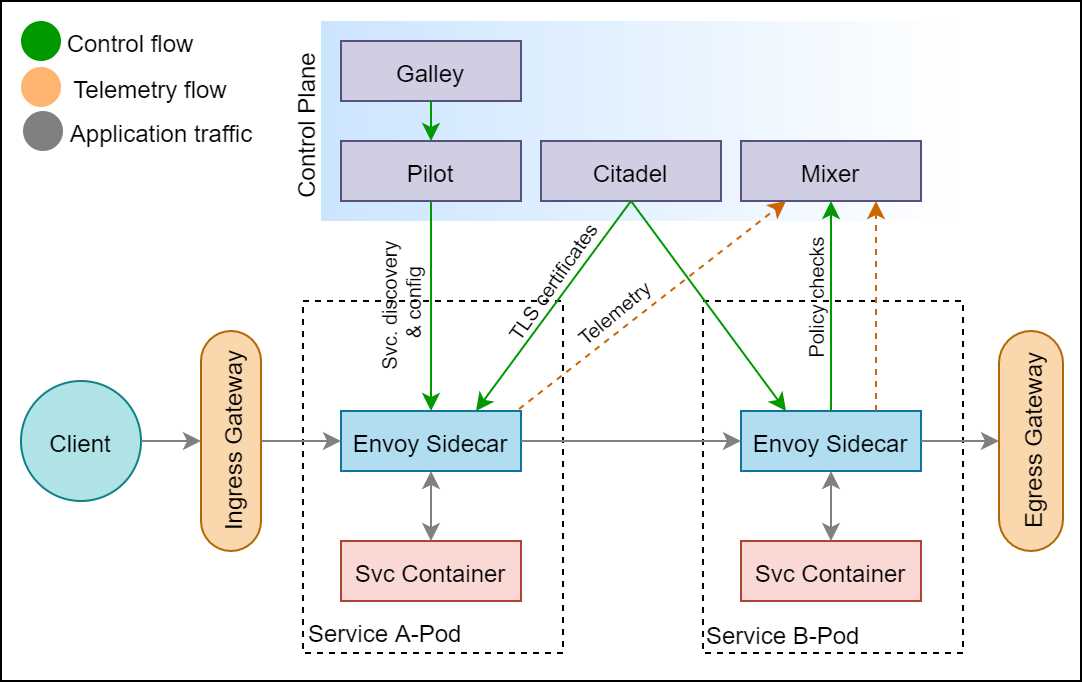

To add services to the Istio service mesh, you only need to deploy an Istio sidecar proxy with every service. As we discussed previously, the Istio sidecar proxy handles the communication between services, which is managed using the Istio control plane. Figure 5 shows the high-level architecture of the Istio service mesh, in which we can see how Istio fills out the service mesh architecture with its own components. We will study the architecture of Istio in the context of how its deployment looks in a Kubernetes cluster.

Figure 5: Istio architecture

As you can see in the previous diagram, the Istio proxy is deployed as a sidecar in the same Kubernetes pod as the service. The proxies thus live within the same namespace as your services, and they act as a conduit for inter-service communication inside the mesh. The control plane of Istio is made up of the Galley, Pilot, Citadel, and Mixer. These components live outside your application in a separate namespace that you will provision only for the Istio control plane services. Let us now discuss each component and its role in Istio.

Ingress/egress gateway

The first and last components that interact with the network traffic are the gateways. By default, in a Kubernetes cluster with Istio mesh enabled, services can accept traffic originating from within the cluster. To expose the services on the mesh to external traffic, Kubernetes natively supports an ingress controller named Kubernetes Ingress, amongst other options, which provides fundamental Layer 7 traffic management capabilities such as SSL termination and name-based binding to virtual hosts (for example, route traffic requested with hostname foo.bar.com to service 1).

Istio created its own ingress and egress gateways primarily for two reasons: first, to avoid duplicate routing configurations in the cluster, one for ingress and another for Istio proxy, both of which only route traffic to a service; second, to provide advanced ingress capabilities such as distributed tracing, policy checking, and advanced routing rules.

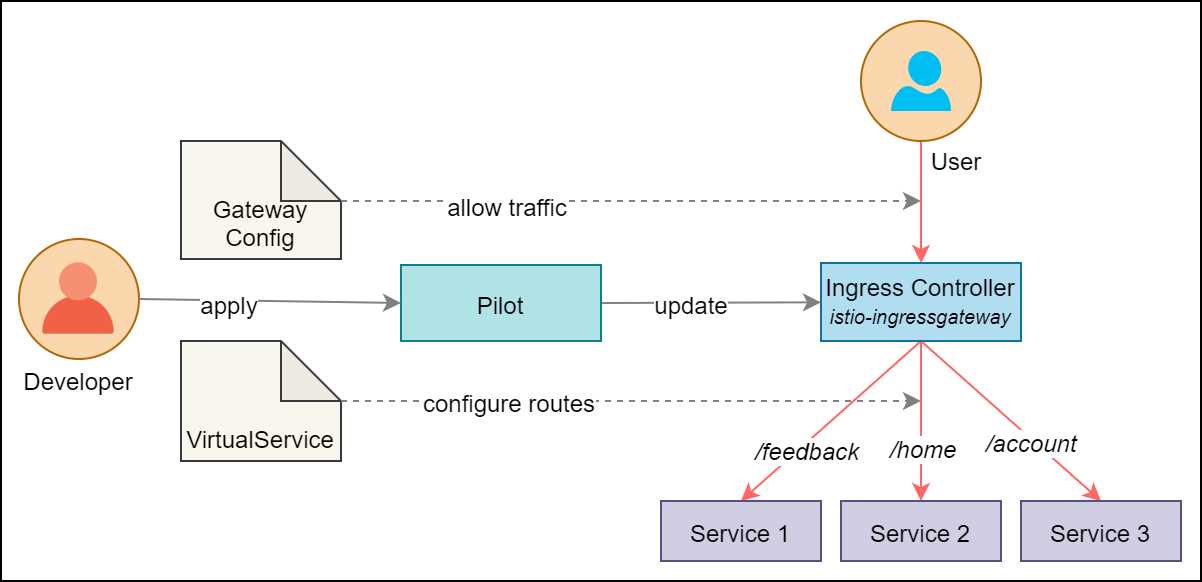

Istio gateways only support configuring routing rules at Level 4 to Level 6 of the network stack, such as specifying routes based on port, host, TLS key, and certificates, which makes it simpler to configure than Kubernetes Ingress. Istio supports a resource named virtual service that instructs the ingress gateway on where to route the requests that were allowed in the mesh by it.

Figure 6: Istio ingress gateway

As shown in the previous diagram, the virtual service specifies routing rules, such as requests to path /feedback should be routed to service 1, and so on. By combining the Istio ingress gateway with virtual service, the same rules that are applied to external traffic for allowing external traffic inside the mesh can be used to control network traffic inside the mesh. For example, for the previous setup, service 2 can reach service 1 at the /feedback endpoint, and external users can reach service 1 at the same path /feedback.

Istio proxy

Istio uses a modified version of the Envoy proxy as the gateway. Envoy is a C++-based Layer 4 and Layer 7 proxy that was initially built by the popular ridesharing company Lyft, and is now a Cloud Native Computing Foundation (CNCF) project. The sidecar proxy makes up the data plane of Istio. Istio utilizes several built-in features of Envoy, such as the following, to proxy the traffic intended to reach a service:

- Dynamic service discovery with support for failover if the requested service is not healthy.

- Advanced traffic routing and splitting controls such as percentage-based traffic split, and fault injection for testing.

- Built-in support for application networking patterns such as circuit breaker, timeout, and retry.

- Support for proxying HTTP/2 and gRPC protocols, both upstream and downstream. With this capability, Envoy can receive HTTP/1.1 connections and convert them to HTTP/2 connections in either direction of application or user.

- Raising of observable signals that are captured by the control plane to support the observability of the system.

- Support for applying live configuration updates without dropping connections. The envoy achieves this by driving the configuration updates through an API, hot loading a new process with a new configuration, and dropping the old one.

As you can see in Figure 6, the Istio proxy or Envoy is deployed as a sidecar alongside your services to take care of ingress and egress network communication of your service. Services on the mesh remain unaware of the presence of the data plane, which acts on behalf of the service to add resilience to the distributed system.

Pilot

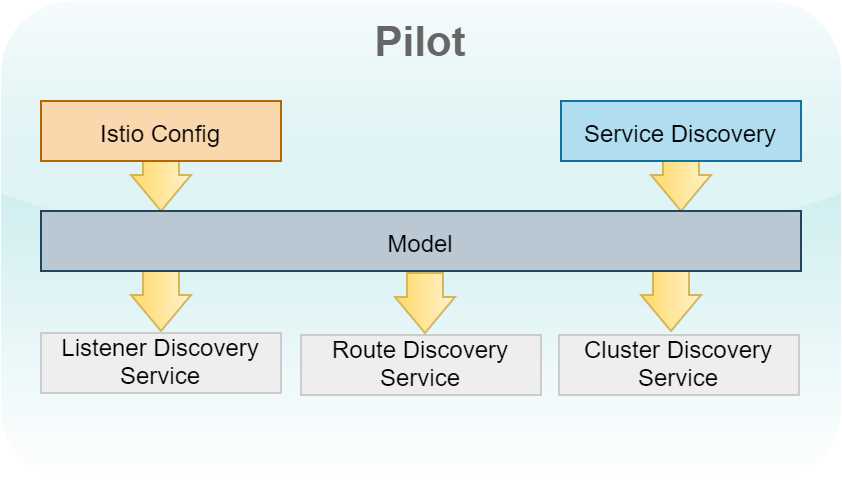

Pilot is one of the components in the control plane of Istio whose role is to interact with the underlying platform’s service discovery system and translate the configuration and endpoint information to a format understood by Envoy or Istio service proxy. Envoy is internally configured using the following discovery services (collectively named xDS APIs):

- Listener (LDS): This service governs the port that Envoy should listen to and the filter conditions on the traffic that arrives on that port, such as protocols.

- Route (RDS): This service identifies the cluster traffic should be sent to, depending on request attributes such as HTTP header.

- Cluster (CDS): A service can be hosted on multiple hosts. This service governs how to communicate with the group of endpoints of a service, such as the certificate to use and the load-balancing strategy to apply.

- Endpoint (EDS): This service helps Envoy interact with a single endpoint of a service.

Pilot is responsible for consuming service discovery data from the underlying platform such as Kubernetes, Consul, or Eureka. It combines the data with Istio configurations applied by the developers and operations and builds a model of the mesh.

Figure 7: Pilot architecture

Pilot then translates the model to xDS configuration, which is consumed by Envoy services by maintaining a gRPC connection with Pilot and receiving data pushed by Pilot. The distinction between the model and xDS configuration helps Pilot maintain loose coupling between Pilot and Envoy.

Currently, Pilot has intrinsic knowledge of the underlying host platform. Eventually, another control plane component named Galley will take over the responsibility of interfacing with the platform. This shift of responsibility will leave Pilot with the responsibility of serving proxy configurations to the data plane.

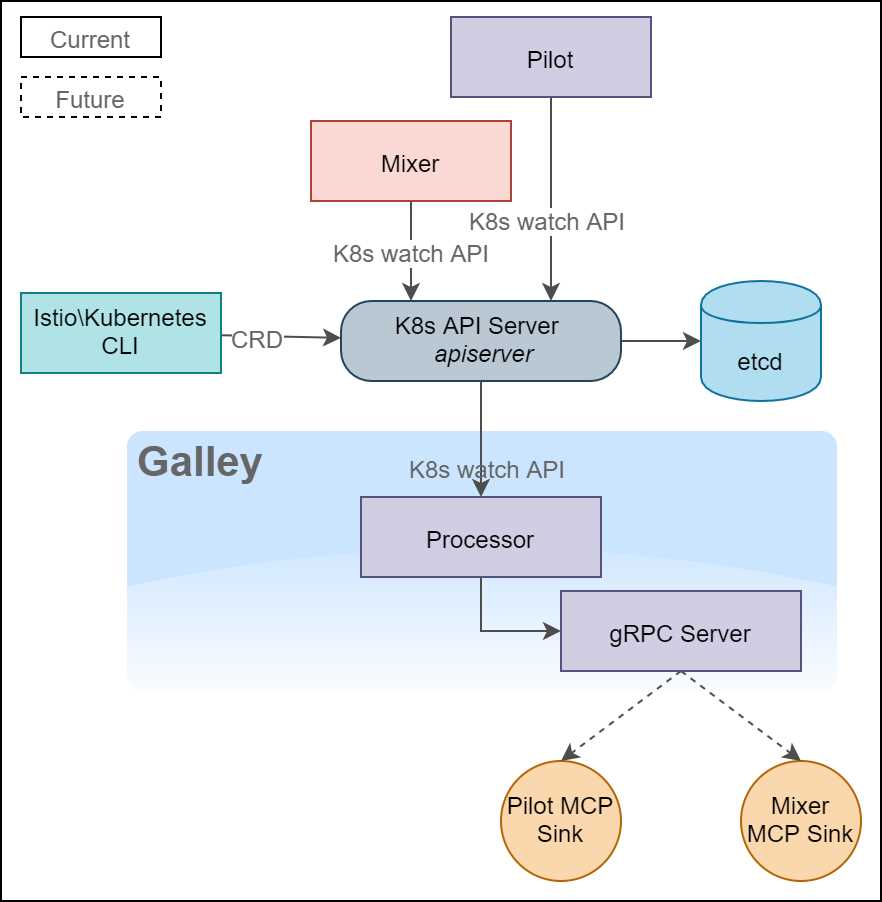

Galley

Galley is responsible for ingesting, processing, and distributing user configurations, and it forms the management plane of the Istio architecture. In the near future, Galley will act as the only interface between the rest of the components of Istio and the underlying platform (such as Kubernetes and virtual machines). In a Kubernetes host, Galley interacts directly with the Kubernetes API server, which is the front-end of the Kubernetes cluster state etcd, to ingest and validate user-supplied configuration and to store it. Galley ultimately makes the configurations available to Pilot and Mixer using the Mesh Configuration protocol (MCP).

In a nutshell, MCP helps establish a pub-sub (publisher-subscriber) messaging system using the gRPC communication protocol and requires a system to implement three models:

- Source: This is the provider of the configuration, which in Istio is Galley.

- Sink: This is the consumer of the configuration, which in Istio are the Pilot and Mixer components.

- Resource: This is the source of the resource that the sink pays attention to. In Istio, this is the configuration that Pilot and Mixer are interested in.

After the source and sinks are set up, the source can push changes to resource to the sinks. The sinks can accept or reject the changes by returning an ACK or NACK signal to the source.

Figure 8: Galley architecture

The previous diagram depicts the dependencies between Galley, Pilot, and Mixer. Pilot, Mixer, and Galley detect changes in the cluster by long polling the Kubernetes watch API. When the cluster changes, the processor component of Galley generates events and distributes them to Mixer and Pilot via a gRPC server. Since Galley is still under development, Pilot and Mixer currently use adapters to connect to the Kubernetes API server. The interaction with the underlying host will be managed only by Galley in the future.

Mixer

Mixer directly interacts with the underlying infrastructure (integration to be replaced with Galley) to perform three critical functions in Istio:

- Precondition checking: Before responding to a request, Istio proxy interacts with Mixer to verify whether the request meets configured criteria such as authentication, whitelist, ACL checks, and so on.

- Quota management: Mixer controls quota management policies for services to avoid contention on a limited resource. These policies can be configured on several dimensions, such as service name and request headers.

- Telemetry aggregation: Mixer is responsible for aggregating telemetry from the data plane and gateways. In the future, Mixer will support aggregating tracing and billing data streams as well.

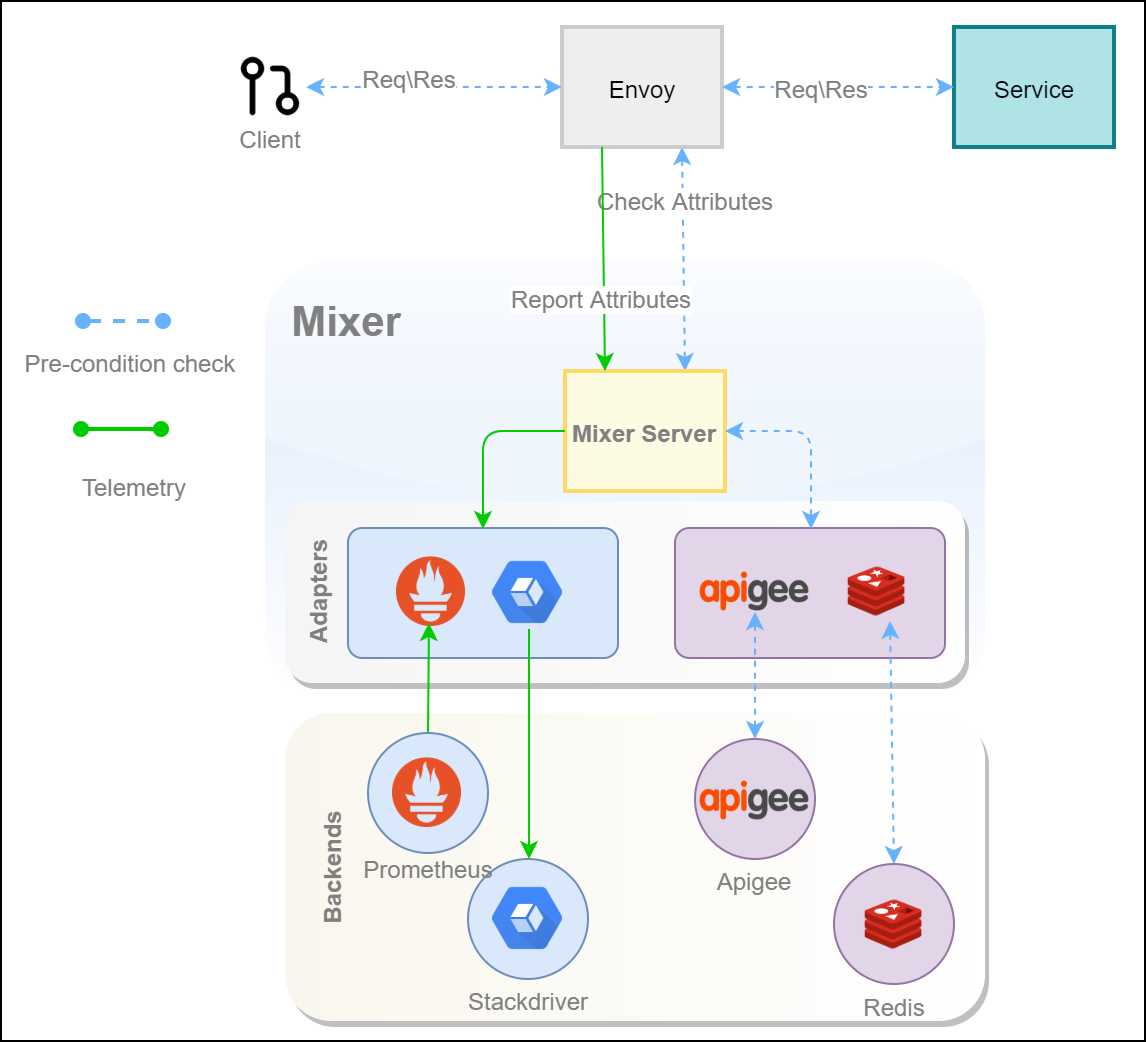

The following high-level design diagram presents how the various components of Istio interact with Mixer.

Figure 9: Mixer architecture

Let’s discuss the life cycle of the two types of data flows in Istio that involve Mixer: precondition checks (including quota management), and telemetry aggregation. Service proxies and gateways invoke Mixer to perform request precondition checks to determine whether a request should be allowed to proceed based on policies specified in Mixer such as quota, authentication, and so on. Some of the popular adapters for precondition checks are Redis for request quota management and Apigee for authentication and request quota management.

Note: Istio release 1.4 has added experimental features to move precondition checks such as RBAC and telemetry from Mixer to Envoy. The Istio team aims to migrate all the features of Mixer to Envoy in the year 2020, after which Mixer will be retired.

Ingress/egress gateways and Istio proxy report telemetry once a request has completed. Mixer has a modular interface to support a variety of infrastructure backends and telemetry backends through a set of native and third-party adapters. Popular Mixer infrastructure backends include AWS and GCP. Some telemetry backends commonly used are Prometheus and Stackdriver. For precondition checks, adapters are used to apply configurations to Mixer, whereas for telemetry, an adapter configuration determines which telemetry is sent to which backend. Once the telemetry is received by a backend, a supported GUI application such as Grafana can be used to display the information persisted by the backend. Note that in Figure 9, the Prometheus connector points from backend to adapter, because Prometheus pulls telemetry from workloads.

Citadel

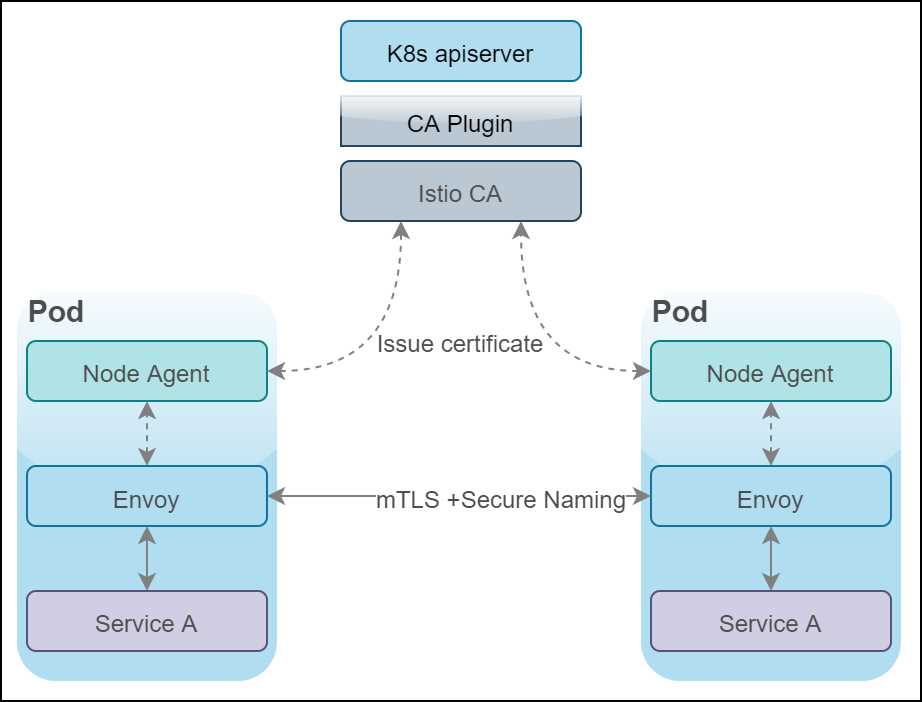

To ascertain the security of the service mesh, Istio supports encrypting the network traffic inside the mesh using mTLS (Mutual Transport Layer Security). Apart from being an encryption scheme, mTLS ensures that both the client and the server verify the certificate to ensure that only authorized systems are communicating with each other.

Citadel plays a crucial role in Istio security architecture by maintaining keys and certificates that are used for authorizing service-to-service and user-to-service communication channels. Citadel is entirely policy-driven, so the developers and operators can specify policies to secure the services that allow only TLS traffic to reach them.

Figure 10: Citadel architecture

Citadel is responsible for issuing and rotating X.509 certificates used for mutual TLS. There are two major components of Citadel. The first one is the Citadel agent, which in the case of Kubernetes host, is called the node agent. The Node agent is deployed on every Kubernetes node, and it fetches a Citadel-signed certificate for Envoy on request. The second component is the certificate authority (CA), which is responsible for approving and signing certificate signing requests (CSRs) sent by Citadel agents. This component performs key and certificate generation, deployment, rotation, and revocation.

In a nutshell, this is how the identity provisioning flow works. A node agent is provisioned on all nodes of the cluster, which is always connected to Citadel using a gRPC channel. Envoy sends a request for a certificate and a key using the secret discovery service (SDS) API to the node agent. The node agent creates a private key and a CSR, and sends the CSR to Citadel for signing. Citadel validates the CSR and sends a signed certificate to the node agent, which in turn is passed on to Envoy. The node agent repeats the CSR process periodically to rotate the certificate.

Citadel has a pluggable architecture, and therefore, rather than issuing a self-signed certificate, it can be configured to supply a certificate from a known certificate authority (CA). With a known CA, administrators can integrate the organization’s existing public key infrastructure (PKI) system with Istio. Also, by using the same CA, the communication between Istio services and non-Istio legacy services can be secured, as both types of services share the same root of trust.

The application security policies using Citadel vary with the underlying host. In Kubernetes-hosted Istio, the following mechanism is followed: When you create a service, Citadel receives an update from the apiserver. It then proceeds to create a new SPIFFE (Secure Production Identity Framework For Everyone) certificate and key pair for the new service and stores the certificate and key pairs as Kubernetes secrets. Next, when a pod for the service is created, Kubernetes mounts the certificate and key pair to the pod in the form of a Kubernetes secret volume. Citadel continues to monitor the lifetime of each certificate and automatically rotates the certificates by rewriting the Kubernetes secrets, which get automatically passed on to the pod.

A higher level of security can be implemented by using a security feature called secure naming. Using secure naming, execution authorization policies such as service A is authorized to interact with service B can be created. The secure naming policies are encoded in certificates and transmitted by Pilot to Envoy. For this activity, Pilot watches the apiserver for new services, generates secure naming information in the form of certificates, and defines what service account or accounts can execute a specific service. Pilot then passes the secure naming certificate to the sidecar Envoy, which ultimately enforces it.

Summary

In this chapter, we discussed the need for the service mesh to abstract network concerns from applications. We covered the overall architecture and the components that make up the data plane, control plane, and management plane of Istio. Istio is a highly customizable service mesh that allows developers and operators to apply policies to each component of Istio, and thus control its behavior. In the next chapter, we will light up Istio on a cluster on your machine.

- 1800+ high-performance UI components.

- Includes popular controls such as Grid, Chart, Scheduler, and more.

- 24x5 unlimited support by developers.