CHAPTER 8

Testing and Advanced Topics

“Trying to improve software quality by increasing the amount of testing is like trying to lose weight by weighing yourself more often. Don’t buy a new scale; change your diet.”

Steve McConnell

In this chapter we are finally going to talk about testing. Sure, testing by itself doesn’t improve the software quality. But it helps to make sure that the functionality is still correct after any new code changes.

Testing scripts in CSCS

Code Listing 76 shows a testing script written in CSCS. I use it myself to do a unit testing of different language features.

Code Listing 76: A test function in CSCS

function test (x, expected) |

Code Listing 77 shows a fragment of my testing script. It heavily uses the test function defined in Code Listing 76. Basically, for any new feature that I introduce in CSCS, I am trying to write at least one unit test, very much like the tests shown in Code Listing 77.

Code Listing 77: A test script in CSCS using the test function

print ("Testing math operators"); x["bla"]["blu"]=113; |

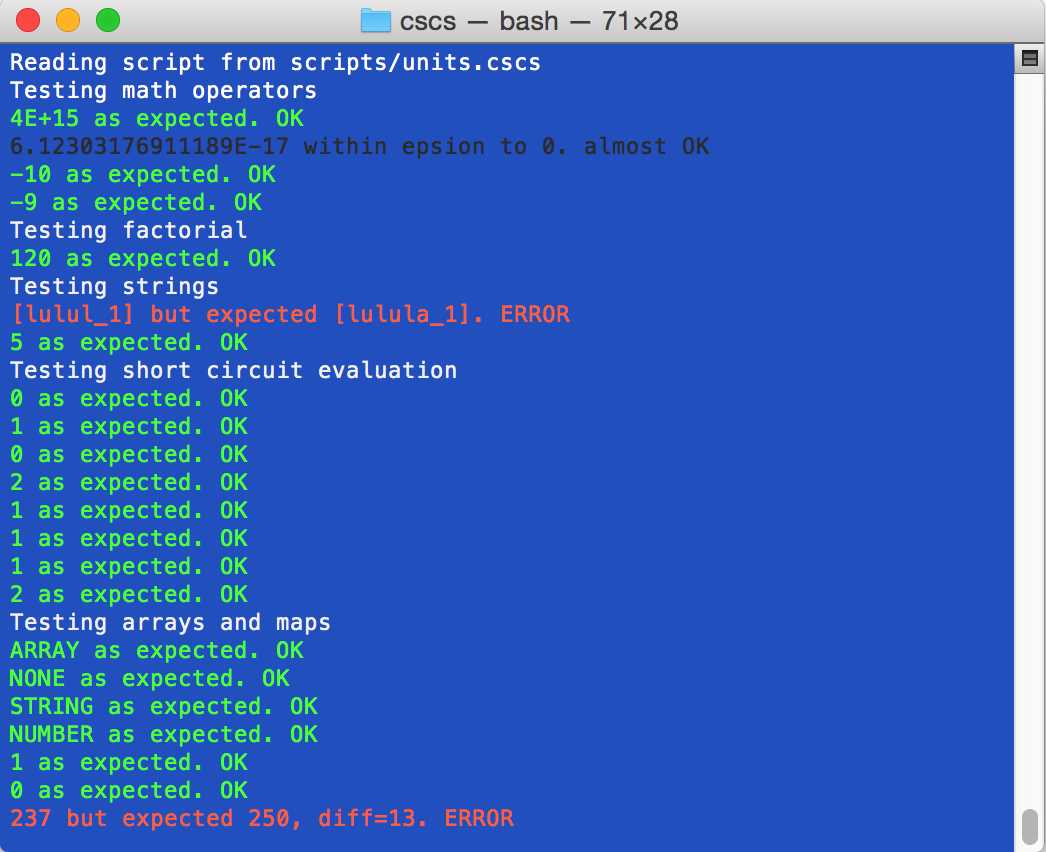

Figure 8 shows the results of running Code Listing 77Error! Reference source not found. on a Mac.

Figure 8: Running CSCS testing script

Logical negation

Another case that needs to be looked at separately is a negation of a Boolean expression. The definition of a logical negation is simple: applied to an expression, it coverts it to false if it is true, and to true, if it is false. In most programming languages this negation is represented by signs ! or ¬, or by a NOT keyword. We are going to use the exclamation sign, but you can redefine it as you wish in the Constants class:

public const string NOT = "!";

We add the implementation of the Boolean negation to the Parser.Split method (shown in Code Listing 4). See details in Code Listing 78Error! Reference source not found.. Note that our implementation supports multiple negations. For example, !!!a is equivalent to !a. But !!a is not necessarily equivalent to a, since applying the logical negation converts number to a Boolean, represented as either 0 or 1 in CSCS, so !!a will be either 0 or 1.

Code Listing 78: The implementation of the Boolean negation in Parser.Split method

int negated = 0; // Code as before... Variable current = func.GetValue(script); // Code as before... } // Implementation of the Utils.IsNotSign: public static string IsNotSign(string data) |

The complete code for the Parser.Split method can be consulted in the accompanying source code. It also deals with the quotes (the original version of the Parser.Split method in Code Listing 4 processes all expressions inside of quotes, instead of taking them as a part of a string).

Running CSCS as a shell program

Code Listing 79 shows an excerpt from Main.cs. There are two modes of operation—in case you supply a file, the whole script containing the file will be executed. It will be done in the Main.ProcessScript method, which is very similar to the IncludeFile functionality in Code Listing 40. Otherwise, the Main.RunLoop method is called, which will process entered commands one by one.

An excerpt from the Main.RunLoop is shown in Code Listing 79, but there are much more than you see there. In particular, there is a functionality to auto-complete file or directory names if you press the Tab key. It’s beyond the scope of this book, but you’re cordially invited to check it out in the accompanying source code.

Code Listing 79: An Excerpt from Main.cs

static void Main(string[] args) ProcessScript("include(\"scripts/functions.cscs\");"); if (args.Length > 0) { private static void RunLoop() script = GetConsoleLine(ref nextCmd, init).Trim(); } |

Running CSCS on non-Windows systems

“I think Microsoft named .NET so it wouldn’t show up in a Unix directory Code Listing.”

Oktal

Using the Mono Framework[16] and Xamarin Studio Community,[17] you can now develop .NET applications on Unix systems, in particular on macOS. Things became even brighter for non-Windows .NET developers after Microsoft acquired Xamarin Inc. in 2016. The Xamarin Studio with Mono framework is what I used to port CSCS on macOS. The code is basically identical on macOS and on Windows, unless you are writing GUI applications. There are a few quirks even for non-GUI development, some of which we are going to see in this section.

Sometimes we need to know whether the code being executed is on Windows or on another platform. It’s easy to figure out at runtime—you can use the Environment.OSVersion property. But what do you do if you want to know which OS your .NET code is being compiled on? You might want to know that in order to compile different code on different OS. Previously you could use #ifdef __MonoCS__ macro for that, but with latest Mono releases, it appears that this macro is no longer set. What I did is the following: I defined the __MonoCS__ symbol in the project properties in Xamarin Studio, so I can still use it when compiling on macOS.

Once you compile your project with Xamarin Studio, how do you run it from the command line?

Code Listing 80 contains a wrapper script; I called it CSCS, so you can just run that script.

Code Listing 80: cscs file: the CSCS starting script on Unix

#!/bin/sh /usr/local/bin/mono cscs.exe "$@" |

The script should be placed in the same directory as the cscs.exe file. It assumes that the Mono Framework was installed at /usr/local/bin/mono. Note that this script will pass on all the arguments to cscs.exe.

Listing directory entries

As an example of a different C# code on different operating systems, let’s see the directory listing function. The directory listing is commonly known as dir on Windows and ls on Unix.

The file system and user permissions are implemented differently on Windows and on Unix. For example, on Unix there is a concept of a user, users of a group to which the user belongs, and all other users. Each of these entities has a combination of read, write, and execution permissions on a file or a directory (for instance, write permissions don’t automatically imply read permissions). You can’t translate such concepts one-to-one to Windows.

We can have both function names, ls and dir, pointing to the same implementation function (Code Listing 68 shows how to do that). Code Listing 81 implements getting details for a file or a directory on either Windows or macOS. We call this function in a loop for each directory entry. To the curious reader: we are implementing here the ls –la Unix command, not just ls.

Code Listing 81: Implementation of Utils.GetPathDetails on Windows and macOS

public static string GetPathDetails(FileSystemInfo fs, string name) string last = fs.LastWriteTime.ToString("MMM dd yyyy HH:mm"); Mono.Unix.FileAccessPermissions.UserRead) != 0 ? 'r' : '-'; Mono.Unix.FileAccessPermissions.UserWrite) != 0 ? 'w' : '-'; Mono.Unix.FileAccessPermissions.UserExecute) != 0 ? 'x' : '-'; Mono.Unix.FileAccessPermissions.GroupRead) != 0 ? 'r' : '-'; Mono.Unix.FileAccessPermissions.GroupWrite) != 0 ? 'w' : '-'; Mono.Unix.FileAccessPermissions.GroupExecute) != 0 ? 'x' : '-'; Mono.Unix.FileAccessPermissions.OtherRead) != 0 ? 'r' : '-'; Mono.Unix.FileAccessPermissions.OtherWrite) != 0 ? 'w' : '-'; Mono.Unix.FileAccessPermissions.OtherExecute) != 0 ? 'x' : '-'; |

To use Unix-specific functions, you have to reference the Mono.Posix.dll library. One of the solutions is to have two project configuration files—one with the __MonoCS__ symbol and Mono.Posix.dll library references (to be used on Unix systems), and another one, without them, to be used on Windows. You may want to have a look at how I did this in the accompanying source code.

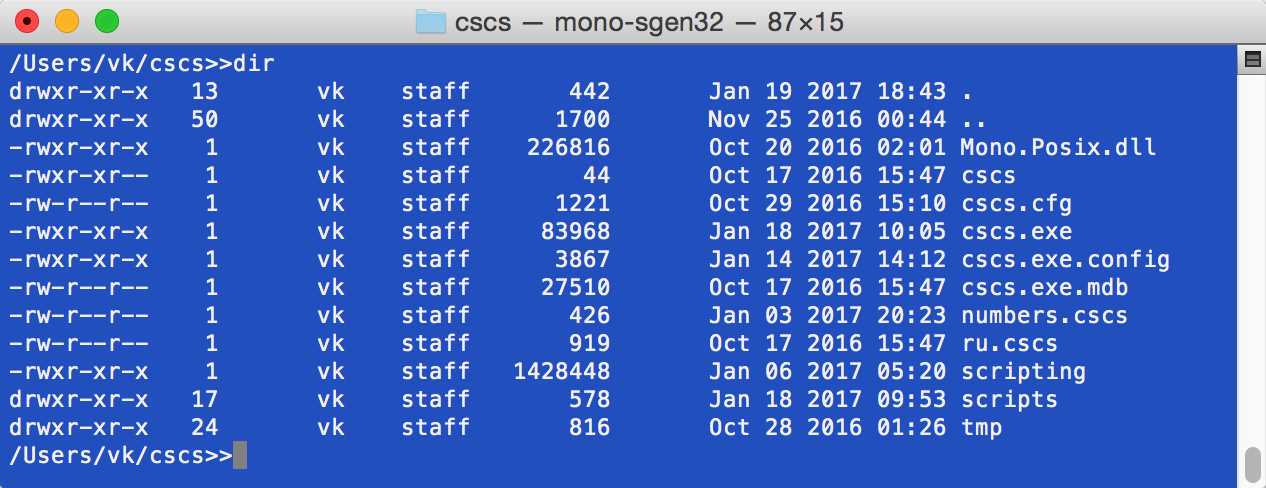

Figure 9: Running dir (ls) command on macOS

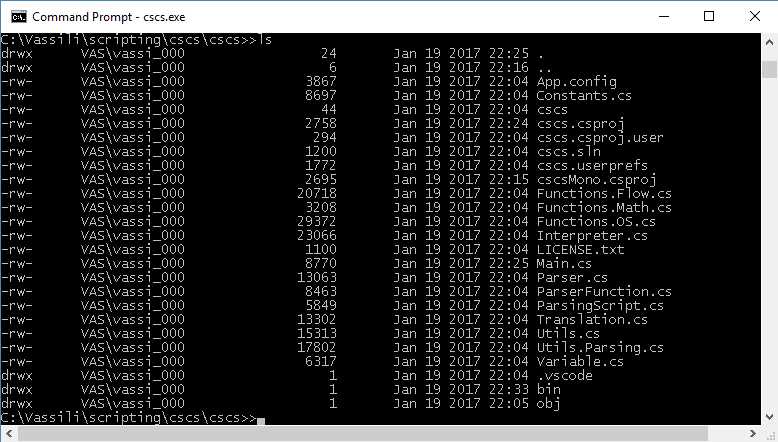

Figure 10: Running ls (dir) command on Windows

Figure 9 shows the CSCS code running on macOS, and Figure 10 shows the CSCS code running on Windows. As you can see, the results are platform dependent.

Command line commands in CSCS

“It won't be covered in the book. The source code has to be useful for something, after all...”

Larry Wall

Analogously to the directory listing command, developed in the previous section, many other commands can be implemented.

shows an implementation of a command to clear the console. It also has also necessary steps to register this command with the parser and allow translations for this command in the configuration file.

Code Listing 82: Implementation of the ClearConsole class

// 1. Definition in Constants class. public const string CONSOLE_CLR = "clr"; // 2. Registration with the parser in Interpreter.Init(). ParserFunction.RegisterFunction(Constants.CONSOLE_CLR, new ClearConsole()); // 3. Registration for keyword translations in Interpreter.ReadConfig(). Translation.Add(languageSection, Constants.CONSOLE_CLR, tr1, tr2); // 4. Implementation of a class deriving from the ParserFunction class. class ClearConsole : ParserFunction |

In the same way, we can implement many more commands. I refer you to the source code area, where you can find the implementation of the following command-prompt commands: copying, moving, and deleting files, changing the directory, starting and killing a process, listing running processes, searching for files, etc.

You now have a tool with which you can create your own programming language. To extend the language, you just add your own functions, analogous to Code Listing 82.

To continue the exploration of this subject, I would suggest downloading the accompanying source code and start playing with it: add a few functions, starting with very simple ones (like printing a specific message to a file). Then you can gradually increase complexity and go towards a functional language. For example, you could implement a function that can read and manipulate large Excel files from CSCS. Here is an example of how you can do it in C#.

I am looking very much forward to your feedback about what can be improved and what functions you have implemented in CSCS!

- 1800+ high-performance UI components.

- Includes popular controls such as Grid, Chart, Scheduler, and more.

- 24x5 unlimited support by developers.