CHAPTER 1

Introduction

“If someone claims to have the perfect programming language, he is either a fool or a salesman or both.”

Bjarne Stroustrup[1]

In this book we are going to develop a customizable, interpreted programming language. We are going to write a parser from scratch without using any external libraries. But why would someone want to write yet another parser and another programming language? To answer these questions, we first need a few definitions and a brief history.

Terminology and a history of parsing in an elevator pitch

The following list of definitions is drawn primarily from Wikipedia; citations have been provided.

A compiler[2] is a program that transforms source code written in a programming language into another computer language, very often being in binary form, ready to be run on a particular operating system. Examples of such languages are C, C++, and Fortran. Java and .NET compilers translate programs into some intermediate code. Just-in-time (JIT) compilers perform some of the compilation steps dynamically at run-time. They are used to compile Java and Microsoft .NET programs into the machine code.

An interpreter[3] is a program that directly executes instructions written in a programming or a scripting language, without previously compiling them. The instructions are interpreted line by line. Some of the examples of such languages are Python, Ruby, PHP, and JavaScript.

A compiler and an interpreter usually consist of two parts: a lexical analyzer and a parser.

A lexical analyzer[4] is a program that converts a sequence of characters into a sequence of tokens (strings with an identified "meaning"). An example would be converting the string “var = 12 * 3;” into the following sequence of tokens: {“var”, “12”, “*”, “3”, “;”}.

A parser[5] is a program that takes some input data (often the sequence produced by the lexical analyzer) and builds a data structure based on that data. At the end, the parser creates some form of the internal representation of the data in the target language.

The parsing process can be done in one pass or multiple passes, leading to a one-pass compiler and to a multi-pass compiler. Usually the language to be parsed conforms to the rules of some grammar.

Edsger Dijkstra invented the Shunting-Yard algorithm to parse a mathematical expression in 1961. In 1965 Donald Knuth invented the LR parser (Left-to-Right, Rightmost Derivation). Its only disadvantages are potentially large memory requirements.[6]

As a remedy to this disadvantage, the LALR parser (Look-Ahead Left-to-Right) was invented by Frank DeRemer in 1969 in his Ph.D. dissertation. It is based on “bottom-up” parsing. Bottom-up parsing is like solving a jigsaw puzzle—start at the bottom of the parse tree with individual characters,[7] then use the rules to connect these characters together into larger tokens as you go. At the end a big single sentence is produced. If not, backtrack and try combining tokens in some other ways.

The LALR parser can be automatically generated by Yacc (Yet Another Compiler Compiler). Yacc was developed in the early 1970s by Stephen Johnson at AT&T Bell Laboratories. The Yacc input is based on an analytical grammar with snippets of C code.

A lexical analyzer, Lex, was described in 1975 by Mike Lesk and Eric Schmidt (Schmidt was able later to parse his way up and become the CEO of Google). Lex and Yacc are commonly used together for parsing.

The top-down[8] parsers construct the parse tree from the top and incrementally work from the top downwards and rightwards. It is mostly done using recursion and backtracking, if necessary. An example of such a parser is a Recursive Descent Parser.

The LL(k) parser is a top-down parser (Left-to-right, Leftmost derivation), where k stands for the number of look-ahead tokens. The higher the k value is, the more languages can be generated by the LL(k) parsers, but the time complexity increases significantly with a larger k.

The Bison parser was originally written by Robert Corbett in the 1980s while doing his Ph.D. at the University of California, Berkeley. Bison converts a context-free grammar into an LALR parser. A context-free grammar[9] is a set of production rules that describe all possible strings of a given formal language. These rules govern string replacements that are applied regardless of the context.

The Flex (Fast lexical analyzer) is an alternative to Lex. It was written by Vern Paxson in 1987 in the University of California, Berkeley. Flex with Bison are replacements of Lex with Yacc.

The framework ANTLR (Another Tool for Language Recognition)[10] was invented by Terence Parr in 1992, while doing his Ph.D. at Purdue University. It is now widely used to automatically generate parsers based on the LL(k) grammar. In particular, this framework can even generate the Recursive Descent Parser. ANTLR is specified using a context-free grammar with EBNF (Extended Backus-Naur Form; it was first developed by Niklaus Wirth from ETH Zurich).

Why yet another programming language?

It is commonly assumed that you need an advanced degree in Computer Science, a few sleepless nights, and a lot of stubbornness to write a compiler.

This book will show you how to write your own compiler without an advanced degree and sleep deprivation. Besides of being an interesting exercise on its own, here are some of the advantages of writing your own language instead of using an existing language or using tools that help you create new languages:

- The language that we are going to develop turns around functions. Besides common functions (defined with the function keyword, as in many languages), all of the local and global variables are implemented as functions as well. Not only that, but all of the language constructs: if – else, try – catch, while, for, break, continue, return, etc., are all implemented as functions as well. Therefore, changing the language is very easy and will involve just modifying one of the associated functions. A new construct (unless, for example) can be added with just a few lines of code.

- The functional programming in the language that we are going to develop is straightforward since all of the language constructs are implemented internally as functions.

- All of the keywords of this language (if, else, while, function, and so on) can be easily replaced by any non-English keywords (they even don’t have to be in the ASCII code, unlike most other languages). Only configuration changes are needed for replacing the keywords.

- The language that we are going to develop can be used as both as a scripting language and as a shell program with many useful command-promt commands, like bash on Unix or PowerShell on Windows (but we will be able to make it more user-friendly than PowerShell).

- Even Python does not have the prefix and postfix operators “++” and “--”, just because Guido van Rossum decided so. There will be no Guido standing behind your back when you write your own language, so you can decide by yourself what you need.

- The number of method parameters is limited to 255 in Java because the Java Execution Committee thought that you would never need more (and if you would, you are not a good software architect in their eyes). This Java “feature” hit me pretty hard once when I used a custom code generator and suddenly nothing compiled anymore. It goes without saying that with your own language, you set the limits—not a remote committee who has no clue about the problem you are working on.

- Any custom parsing can be implemented on the fly. Having full control over parsing means less time searching for how to use an external package or a RegEx library.

- Using parser generators, like ANTLR, Bison, or Yacc, has a few limitations. The requirement for many tools is to have a distinct first lexical analysis phase, meaning the source file is first converted to a stream of tokens, which have to be context-free. Even C++ itself cannot be created using such tools because C++ has ambiguities, where parsing depends on the context. So there are just too many things that the generators do not handle. Our parser won’t have any of these requirements—you will decide how your language should look. Furthermore, the parsing errors can be completely customized: something that standard parsing tools do not do.

- You won’t be using any Regular Expressions at all! This is a showstopper for a few people who desperately need to parse an expression but are averse to the pain and humiliation induced by the regex rules.

What will be covered in this book?

I am going to show you how to write an interpreter for a custom language. This interpreter is based on a custom parsing algorithm, which I call the Split-and-Merge algorithm.

Using this algorithm, we can combine the lexical analysis and the parser, meaning the parser will do the lexical analysis as well. There will be no formal definition of the grammar—we will just add the new functionality as we go. All the keywords and symbols can be changed ad-hoc in a configuration file.

For brevity and simplicity, I am going to call the language that we are going to develop CSCS (Customized Scripting in C#). In CSCS we are going to develop the following features:

- Mathematical and logical expressions, including multiple parentheses and compound math functions

- Basic control flow statements: if – else; while; for; break; continue, etc.

- Exception handling: try – catch and throw statements

- Prefix and Postfix ++ and -- operators

- Compound assignment operators

- Custom functions written in CSCS, including recursive functions

- Including modules from other files with the include keyword

- Using CSCS as a shell language (a command-line prompt)

- Implementing command-line functions

- Arrays and dictionaries with an unlimited number of dimensions

- Mixing different types as keys in arrays and dictionaries

- Dynamic programming

- Creating and running new threads

- Supporting keywords in multiple languages

- Possibility to translate function bodies from one language to another

In short, we are going to develop not a new programming language, but rather a framework with which it will be easy to create a new programming language with all the custom features you might need.

We are going to write code that will run on both Windows and macOS. For the former, we’ll be using Microsoft Visual Studio, and for the latter, Xamarin Studio Community.

Hello World in CSCS

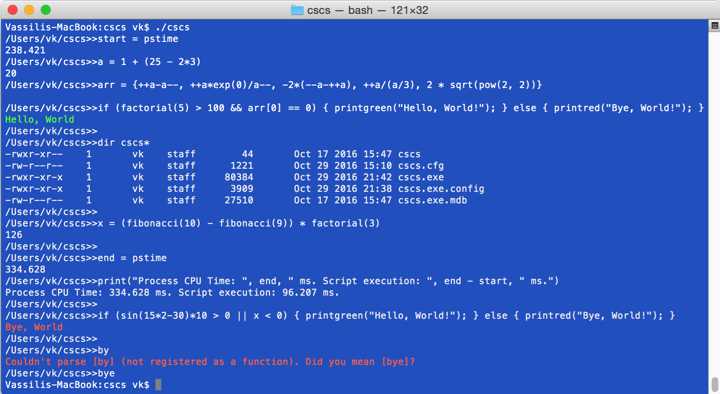

The following two screenshots will give you an idea of some of the features we are going to cover in this book. Both screenshots show the command line (or shell mode) of the CSCS operation. Figure 1 has a screenshot of a “Hello, World!” session with the CSCS language on a Mac.

Figure 1: Sample execution of CSCS on a Mac

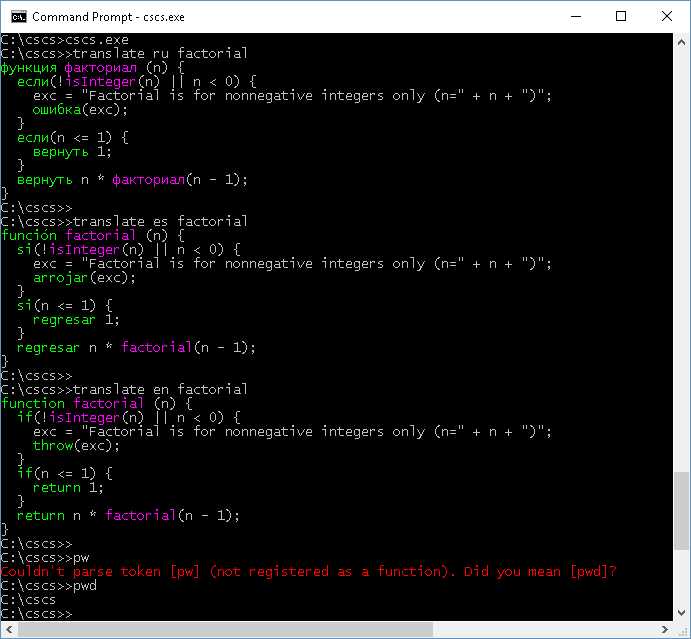

Figure 2 has a sample session on a Windows PC. There you can see how the keywords of a function, implemented in CSCS, can be translated to another language.

Figure 2: Sample execution of CSCS on Windows

The complete source code of the CSCS language developed in this book is available here.

Even though the implementation language will be C#, you’ll see that it will be easy to implement this scripting language in any other object-oriented language. As a matter of fact, I also implemented CSCS in C++, the implementation is available here.

- 1800+ high-performance UI components.

- Includes popular controls such as Grid, Chart, Scheduler, and more.

- 24x5 unlimited support by developers.