CHAPTER 4

Functions, Functions, Functions

“Developers, developers, developers!”

Steve Ballmer, encouraging more developers for Windows Phone

As you saw in the previous chapter, implementing a class deriving from the ParserFunction class is the main building block of the programming language we are creating.

In this chapter we are going to see how to implement some popular language constructs, all using the same technique: creating a new class, deriving from the ParserFunction class, registering it with the parser, and so on. The more functions we can create using this approach, the more power and flexibility will be added to the language.

Writing to the console

Code Listing 24 shows an example of a very useful function implemented in C#, which can be called from the CSCS code.

Code Listing 24: The implementation of the PrintFunction class

class PrintFunction : ParserFunction internal PrintFunction(bool newLine = true) { internal PrintFunction(ConsoleColor fgcolor) { protected override Variable Evaluate(ParsingScript script) if (m_changeColor) { public static void PrintColor(string output, ConsoleColor fgcolor) { |

To extract the arguments (what to print), the Utils.GetArgs auxiliary function is called (see Code Listing 25). It returns a list of variables whose values have already been calculated by calling the whole Split-and-Merge algorithm recursively, if necessary. For example, if the argument list is “25, “fu” + “bar”, sin(5*2 – 10)”, the Utils.GetArgs function will return the following list: {25, “fubar”, 0} (because sin(0) = 0).

Code Listing 25: The implementation of the Utils.GetArgs method

public static List<Variable> GetArgs(ParsingScript script, script.Pointer); // After the statement above, tempScript.Parent will point to the last // character belonging to the body between start and end characters. while (script.Pointer < tempScript.Pointer) { // Eat closing parenthesis, if there is one, but only if it closes // the current argument list, not one after it. script.MoveForwardIf(Constants.SPACE); |

To print a CSCS variable, we have to represent it as a string. It’s easy to do that if the variable is a string or a number. But what if it’s an array? Then we convert each element of the array to a string, possibly using recursion (see Code Listing 26). If the parameter isList is set to true, opening and closing curly braces will be added to the result.

Code Listing 26: The implementation of the Variable.AsString method

public string AsString(bool isList = true, if (Type == VarType.STRING) { if (Type == VarType.NONE || m_tuple == null) { for (int i = 0; i < m_tuple.Count; i++) { if (isList) { return sb.ToString(); |

This is how we register printing functions, printing in a specified or in a default color:

ParserFunction.RegisterFunction(Constants.PRINT,

new PrintFunction());

ParserFunction.RegisterFunction(Constants.PRINT_BLACK,

new PrintFunction(ConsoleColor.Black));

ParserFunction.RegisterFunction(Constants.PRINT_GREEN,

new PrintFunction(ConsoleColor.Green));

ParserFunction.RegisterFunction(Constants.PRINT_RED,

new PrintFunction(ConsoleColor.Red));

The constants are defined as follows:

public const string PRINT = "print";

public const string PRINT_BLACK = "printblack";

public const string PRINT_GREEN = "printgreen";

public const string PRINT_RED = "printred";

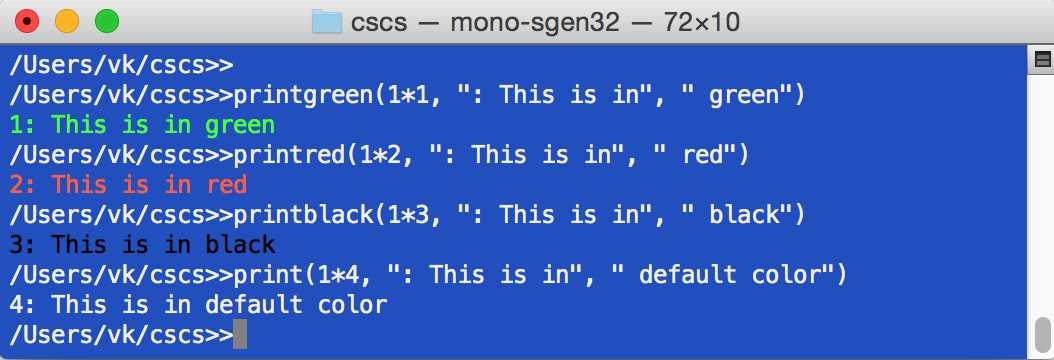

Analogously, you can add printing any other color you wish. Figure 5 contains a sample session with CSCS playing with different colors.

Figure 5: Printing in different colors

Reading from the console

Now let’s see a sister of the writing to the console function—reading from the console. Details below in Code Listing 27.

Code Listing 27: The implementation of the ReadConsole class

class ReadConsole : ParserFunction } |

There are two cases: when we read a number, and when we read a string. Correspondingly, we register two functions with the parser:

public const string READ = "read";

public const string READNUMBER = "readnum";

ParserFunction.RegisterFunction(Constants.READ, new ReadConsole());

ParserFunction.RegisterFunction(Constants.READNUMBER, new ReadConsole(true));

Analogously, we can add functions to read different data structures, for example, to read the whole array of numbers or strings.

Next we’ll see an example of a CSCS script using different constructs that we’ve implemented so far.

An example of the CSCS code

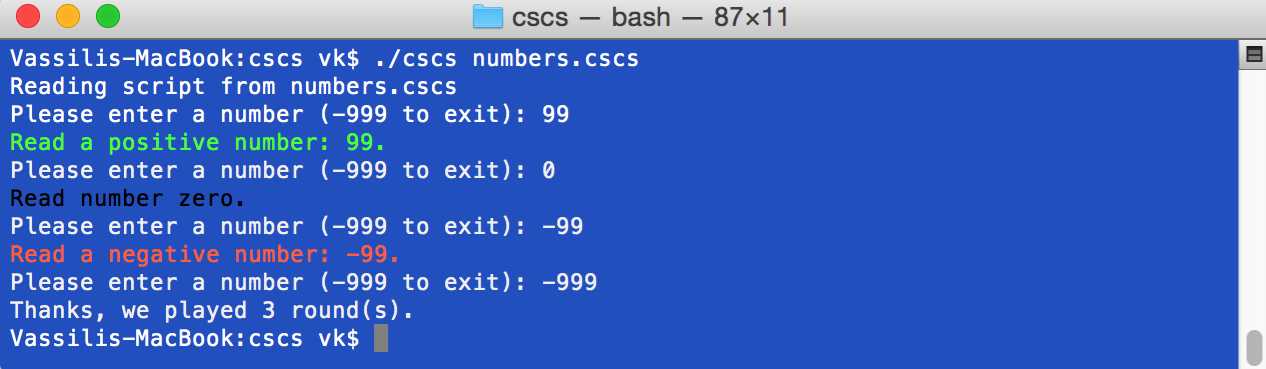

Code Listing 28 shows an example of the CSCS code using while, break, and if control flow structures that we discussed in the previous chapter, and printing in different colors.

Code Listing 28: CSCS code to print in different colors depending on the user input

round = 0; if (number == -999) { |

To test our script, we save the contents of Code Listing 28 to the numbers.cscs file and then run it, as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6: Sample run of the numbers.cscs script

Working with strings in CSCS

In this section we are going to see some of the examples of classes deriving from the ParserFunctions class that implement string-related functionality. We are going to see that most of this functionality is already implemented in C#, so our classes are just wrappers over the existing C# functions and methods.

Code Listing 29: The implementation of the ToUpperFunction class

class ToUpperFunction : ParserFunction Utils.CheckNotEmpty(script, varName, m_name); // 2. Get the current value of the variable. |

Code Listing 30 provides an implementation of converting all characters of a string to the upper case. The Utils.GetToken is a convenience method that extracts the next string token from the parsing script (it doesn’t call the Split-and-Merge algorithm). It’s a relatively straightforward function, and you can check out its implementation in the accompanying source code.

Code Listing 30 implements the IndexOfFunction class to search for a substring in a string. The C# String.IndexOf function, which is used there, has many more optional parameters (for example, from which character to search or which type of comparison to use). These options can be easily added to the IndexOfFunction.

Code Listing 30: The implementation of the IndexOfFunction class

class IndexOfFunction : ParserFunction // 2. Get the current value of the variable. |

Code Listing 31 shows the implementation of the substring function. Note that it has two arguments: the user can optionally supply the length of the substring.

Code Listing 31: The implementation of the SubstrFunction class

class SubstrFunction : ParserFunction // 2. Get the current value of the variable. if (lengthAvailable) { if (init.Value + length.Value > arg.Length) { Variable newValue = new Variable(substring); |

Then we register ToUpperFunction, IndexOfFunction, and SubstrFunction with the parser as follows:

public const string TOUPPER = "toupper";

public const string INDEX_OF = "indexof";

public const string SUBSTR = "substr";

ParserFunction.RegisterFunction(Constants.TOUPPER, new ToUpperFunction());

ParserFunction.RegisterFunction(Constants.INDEX_OF, new IndexOfFunction());

ParserFunction.RegisterFunction(Constants.SUBSTR, new SubstrFunction());

Code Listing 31 calls a few auxiliary functions that are used extensively in our implementation of CSCS, mostly to save on typing. Some of these functions are shown inCode Listing 32.

Code Listing 32: Functions to check for correct input

public static void CheckNonNegativeInt(Variable variable) "Expected a non-negative integer instead of [" + public static void CheckInteger(Variable variable) public static void CheckNumber(Variable variable) public static void CheckNotEmpty(ParsingScript script, string varName, string name) { |

Code Listing 33 shows examples of using some of the string functions in CSCS.

Code Listing 33: A sample CSCS code for working with strings

str = "Perl - The only language that looks the same before and after " + "RSA encryption. -- Keith Bostic"; |

Mathematical functions in CSCS

Implementing a mathematical function in CSCS is even easier than implementing a string function. See Code Listing 34, which shows how to implement a function to round a number to the closest integer.

The only missing part is to define a name for this function and register it with the parser:

public const string ROUND = "round";

ParserFunction.RegisterFunction(Constants.ROUND, new RoundFunction());

Code Listing 34: The implementation of the RoundFunction class

class RoundFunction : ParserFunction |

Finding variable types in CSCS

All of the variables in CSCS have a corresponding Variable object in C# code. It would be convenient to be able to extract some properties of this variable, such as its type. Code Listing 35 implements this functionality. The Evaluate method of the TypeFunction class has a few method invocations that deal with arrays. We are going to look more closely at arrays in the “Using arrays in CSCS” section in Chapter 6 Operators, Arrays, and Dictionaries.

The only missing part is to define a name for this function and register it with the parser:

public const string TYPE = "type";

ParserFunction.RegisterFunction(Constants.TYPE, new TypeFunction());

Code Listing 35: The implementation of the TypeFunction class

class TypeFunction : ParserFunction List<Variable> arrayIndices = Utils.GetArrayIndices(ref varName); |

As you can see, basically, you can implement in CSCS anything that can be implemented in C#.

Also note that the CSCS language we are creating can be easily converted to a functional programming language. In a functional language, the output value of a function depends only on the arguments, so the change would be not to have global variables that can have different values between two function calls.

Working with threads in CSCS

“Giving pointers and threads to programmers is like giving whisky and car keys to teenagers.”

P. J. O'Rourke

In this section we are going to see on some of the thread functions. In particular, you’ll see that the syntax of creating a new thread can be very simple.

In Code Listing 36 we define three thread-related functions: ThreadFunction (to create and start a new thread; returns the id of the newly created thread), ThreadIDFunction (to get and return the thread id of the current thread), and SleepFunction (to put thread execution to sleep for some number of milliseconds).

Code Listing 36: The implementation of the Thread-related classes

class ThreadFunction : ParserFunction Constants.END_GROUP); } static void ThreadProc(Object stateInfo) class ThreadIDFunction : ParserFunction class SleepFunction : ParserFunction |

As you can see, all of these classes are thin wrappers over their C# counterparts. The argument of the thread function can be any CSCS script, including a CSCS function (we’ll see functions in CSCS in

Chapter 5 Exceptions and Custom Functions). This is how we register thread functions with the parser:

public const string THREAD = "thread";

public const string THREAD_ID = "threadid";

public const string SLEEP = "sleep";

ParserFunction.RegisterFunction(Constants.THREAD, new ThreadFunction());

ParserFunction.RegisterFunction(Constants.THREAD_ID, new ThreadIDFunction());

ParserFunction.RegisterFunction(Constants.SLEEP, new SleepFunction());

Code Listing 37 contains sample code using the three functions above. It has a for loop, which we are going to see in the “Implementing the for-” section in Chapter 6.

Code Listing 37: Playing with threads in CSCS

for (i = 0; i < 5; i++) { sleep(2000); // Sample run of the script above: Started thread3 in main -->> Starting in thread3 Started thread4 in main -->> Starting in thread4 Started thread5 in main -->> Starting in thread5 Started thread6 in main -->> Starting in thread6 Started thread7 in main -->> Starting in thread7 <<-- Finishing in thread3 <<-- Finishing in thread5 <<-- Finishing in thread6 <<-- Finishing in thread4 <<-- Finishing in thread7 Main completed in thread1 |

Inter-thread communication in CSCS

Once you know how to start a new thread, you would probably want to be able to share resources and send signals among threads (for example, when a thread finishes processing of a task).

The former can be implemented in C# using locks, and the latter using event wait handles.

The advantage of using custom locking and synchronization mechanisms in our scripting language is that you can have an even simpler syntax than the one in C#, as you’ll see soon.

Code Listing 38 defines LockFunction, which implements the thread-locking functionality, and SignalWaitFunction, which implements signaling between threads (this functionality is also commonly known as a “condition variable” in other languages).

From here you can get more fancy and implement, for instance, a readers-writer lock, when you allow a read-access to a resource to multiple threads and a write access to just one thread.

Code Listing 38: The implementation of the LockFunction and SignalWaitFunction classes

class LockFunction : ParserFunction protected override Variable Evaluate(ParsingScript script) Constants.END_ARG); class SignalWaitFunction : ParserFunction |

This is how we register these functions with the parser:

public const string LOCK = "lock";

public const string SIGNAL = "signal";

public const string WAIT = "wait";

ParserFunction.RegisterFunction(Constants.LOCK, new LockFunction());

ParserFunction.RegisterFunction(Constants.SIGNAL,

new SignalWaitFunction(true));

ParserFunction.RegisterFunction(Constants.WAIT,

new SignalWaitFunction(false));

39 contains sample code using the SignalWaitFunction function. It uses a custom CSCS function threadWork. We’ll see custom functions in CSCS in Chapter 5: Exceptions and Custom Functions.

Code Listing 39: Thread synchronization example in CSCS

function threadWork() print(" Starting thread work in thread", threadid()); // Sample run of the script above: Reading script from scripts/temp.cscs Main, starting new thread from 1 Main, waiting for thread in 1 Starting thread work in thread3 Finishing thread work in thread3 Main, wait returned in 1 |

Conclusion

In this chapter we implemented a few useful functions: writing to the console in different colors, reading from the console, implementing mathematical functions, working with strings, threads, and some others. The goal was to show that anything that can be implemented in C#, can be implemented in CSCS as well.

In the next chapter we are going to see how to implement exceptions and custom functions, how to add local and global files, and a few examples.

- 1800+ high-performance UI components.

- Includes popular controls such as Grid, Chart, Scheduler, and more.

- 24x5 unlimited support by developers.