CHAPTER 3

Basic Control Flow Statements

“Talk is cheap. Show me the code.”

Linus Torvalds

In the previous chapter we created basic building blocks for our programming language, CSCS. Namely, we saw how to parse a basic mathematical expression and how to define a function and add it to CSCS.

In this chapter we are going to develop the basic control flow statements: if – else, while, and some others. You will see that they are all implemented almost identically—as functions (very similar to the implementation of the exponential function in Code Listing 10). We are going to delay the implementation of the for loop until Chapter 6 Operators, Arrays, and Dictionaries, where we are going to see it together with arrays.

We are also going to muscle up the basic parsing algorithm that we started in the previous chapter by adding to it some missing features that we mentioned at the end of the last chapter.

Implementing the If – Else If – Else functionality

To implement the if statement functionality, we use the same algorithm we used in the “Registering a function with the ” section in Chapter 2.

- Define the if constant in the Constants class:

public const string IF = "if";

- Implement a new class, IfStatement, having ParserFunction as its base class, and override its Evaluate method. There is going to be a bit more work implementing the if statement; the real implementation is forwarded to the Interpreter class (see Code Listing 15).

- Register this function with the parser:

ParserFunction.RegisterFunction(Constants.IF, new IfStatement());

Code Listing 15: The implementation of the if-statement

class IfStatement : ParserFunction |

Note that we defined only if as a function, and did not do anything with the else if and else control flow statements. The reason is that else if and else are going to be processed all together in the if statement processing.

The main reason of implementing the if statement in a different class is that the implementation will use a few functions and methods that we will be sharing with other control flow statements (for example, with while and for). See Code Listing 16 for the implementation of the if statement.

Code Listing 16: The processing of the if statement

internal Variable ProcessIf(ParsingScript script) SkipRestBlocks(script); ParsingScript nextData = new ParsingScript(script); else if (Constants.ELSE_LIST.Contains(nextToken)) { |

First, we note where we are in the parsing script within the startIfCondition variable, and then we apply the Split-and-Merge algorithm to the whole expression in parentheses after the if keyword in order to evaluate the if condition.

Constants.END_ARG_ARRAY is an array consisting of a ) character, meaning we are going to apply the Split-and-Merge algorithm to the passed string until we get the closing parenthesis character that matches this opening parenthesis. The important thing here is the statement “that matches this opening parenthesis.”

It means that if we get another opening parenthesis before we get a closing parenthesis, we will recursively apply the Split-and-Merge algorithm to the whole expression between the next opening parenthesis and its corresponding closing parenthesis.

If the condition in the if statement is true, then we will be within the if (isTrue) block. There we call the ProcessBlock method to process all the statements of the if block. See Code Listing 17.

Code Listing 17: The implementation of the Interpreter.ProcessBlock method

Variable ProcessBlock(ParsingScript script) |

Inside of the ProcessBlock method, we recursively apply the Split-and-Merge algorithm to all of the statements between the Constants.START_GROUP (defined as { in the Constants class) and Constants.END_GROUP (defined as } in the Constants class) characters. ParsingScript.GoToNextStatement is an auxiliary method that moves the current script pointer to the next statement and returns an integer greater than zero if the Constants.END_GROUP has been reached. See Code Listing 18 for details.

Code Listing 18: The implementation of the ParsingScript.GoToNextStatement method

public int GoToNextStatement() while (StillValid()) { endGroupRead++; return endGroupRead; |

Let’s continue with the processing of the if statement in Code Listing 16.

If one of the statements inside of the if block is a break or a continue statement, we must finish the processing and propagate this “break” or “continue” up the stack (the if statement that we are processing may be inside of a while or a for loop).

We’ll see how to implement the break and continue control flow statements in the next section.

So basically, we need to skip the rest of the statements in the if block. For that we return back to the beginning of the if block and skip everything inside it. The implementation is shown in Code Listing 19.

Note that we also skip all nested blocks inside of the curly braces and throw an exception if there is no match between opening and closing curly braces.

Code Listing 19: The implementation of the Interpreter.SkipBlock method

void SkipBlock(ParsingScript script) while (startCount == 0 || startCount > endCount) { |

Once we know that the if condition is true and we have executed all statements that belong to that if condition, we must skip the rest of the statements that are part of the if control flow statement (the rest are also the else if and else conditions and their corresponding statements). This is done in Code Listing 20: basically we call the SkipBlock method in a loop.

Code Listing 20: The implementation of the Interpreter.SkipRestBlocks method

void SkipRestBlocks(ParsingScript script) if (!Constants.ELSE_IF_LIST.Contains(nextToken) && script.Pointer = nextData.Pointer; |

We already saw what happens if the condition in the if statement is true. When it is false, we just skip the whole if block and start looking at what comes next. If an else if statement comes next, then we call recursively the ProcessIf method.

If it is an else statement, then we just need to execute all of the statements inside of the else block. We can do that by calling the ProcessBlock method that we already saw in Code Listing 19.

Note: It’s important to note that the if statement always expects curly braces. You can change this functionality in ProcessBlock and SkipBlock methods in case there is no curly brace character after the if condition. The same applies to the while and for loops that follow.

Now let’s see the implementation of the break and continue control flow statements.

Break and continue control flow statements

As you saw in Code Listing 17, there are two additional variable types in the if statement processing:

if (result.Type == Variable.VarType.BREAK ||

result.Type == Variable.VarType.CONTINUE) {

return result;

}

They are not present in Code Listing 3, but they are used for the typical break and continue control flow statements. How can we implement the break and continue statements in CSCS?

The break and continue control flow statements are implemented analogous to the exponential function and to the if statement in the previous section, using the three steps we described before. But first, let’s also extend the definition of the enum VarType in Code Listing 3:

public enum VarType { NONE, NUMBER, STRING, ARRAY, BREAK, CONTINUE };

Then, according to our three steps:

- We define the corresponding constants in the Constants class:

public const string BREAK = "break";

public const string CONTINUE = "continue";

- We introduce the Break and Continue functions, deriving from the ParserFunction class (see Code Listing 21).

- We register the newly created functions with the parser:

ParserFunction.RegisterFunction(Constants.BREAK, new BreakStatement());

ParserFunction.RegisterFunction(Constants.CONTINUE, new ContinueStatement());

Code Listing 21: The implementation of the Break and Continue functions

class BreakStatement : ParserFunction class ContinueStatement : ParserFunction |

That’s it! So how do these Break and Continue functions work?

As we saw in Code Listing 16, as soon as we get a break or a continue statement, we stop all the processing and return (propagate it) to whoever called this statement.

Break and Continue make sense in while and for loops. Note that here we won’t throw any error if there is no while or for loop, which can use these break and continue statements—we just stop processing the current block.

If this bothers you, you can change this functionality and throw an exception if there is no while or for loop (we would probably need an additional variable to keep track of nested while and for loops).

In the next two sections we are going to see how the break and continue statements are used in while and for loops.

Implementing the while loop

The implementation of the while loop is analogous to the implementation of the if control flow statement. The while loop is also implemented as a function object deriving from the ParserFunction class. I hate being repetitive, but again, there are three steps: defining the corresponding constant, implementing an Evaluate method of a class deriving from the ParserFunction class, and gluing it all together by registering this newly created class with the parser. So we skip these steps.

Now we can also reuse a few methods that we saw in the if-statement implementation.

Analogous to the ProcessIf method in Code Listing 16, we implement the ProcessWhile class in Code Listing 22. They do look similar—we just check for the condition to be true not once, but in a while loop.

Code Listing 22: The implementation of the While Loop

internal Variable ProcessWhile(ParsingScript script) int cycles = 0; Variable condResult = script.ExecuteTo(Constants.END_ARG); Variable result = ProcessBlock(script); |

Note that we also check the total number of loops and compare it with the MAX_LOOPS variable.

This number can be set in the configuration file. If it’s greater than zero, then we stop after this number of loops. No programming language defines a number after which it is likely to suppose that you have an infinite loop. The reason is that the architects of a programming language never know in advance what would be an “infinite” number for you. However, you know your own needs better than those architects, so you can set this limit to an amount that is reasonable for you—say to 100,000—if you know that you’ll never have as many loops, unless you have a programming mistake.

We also break from the while loop when having this condition:

if (result.IsReturn || result.Type == Variable.VarType.BREAK) {

script.Pointer = startWhileCondition;

break;

}

Note that before breaking out of the while loop, we reset the pointer of the parsing script to the beginning of the while condition. We are doing this because it’s just easier to skip the whole block between the curly braces by calling the SkipBlock method, but you could also skip just the rest of the block; then you would need to keep track of the number of opening and closing curly braces, already processed inside of the while block.

We saw how to trigger the type of the result Variable.VarType.BREAK at the end of last section. The IsReturn property will be set to true when a return statement is executed inside a function. We’ll see how it’s done in the next chapter.

Short-circuit evaluation

The short-circuit evaluation is used when calculating Boolean expressions. It simply means that only necessary conditions need to be evaluated. For example, if condition1 is true, then in “condition1 || condition2”, the condition2 does not need to be evaluated since the whole expression will be true regardless of the condition2.

Similarly, if condition1 is false, then in “condition1 && condition2”, the condition2 does not need to be evaluated as well since the whole expression will be false anyway. This is implemented in Code Listing 23.

Code Listing 23: The implementation of the short-circuit evaluation

static void UpdateIfBool(ParsingScript script, Variable current) |

The method Utils.SkipRestExpr just skips the rest of the expression after “&&” or “||”. The implementation is analogous to the implementation of the SkipBlock and SkipRestBlocks we saw before, so we won’t show it here—nevertheless, it can be consulted in the accompanying source code.

Where do we call this new UpdateIfBool method from? It’s called from the Split method, shown in Code Listing 4, right before adding the new item to the list:

UpdateIfBool(script, cell);

listToMerge.Add(cell);

UML class diagrams

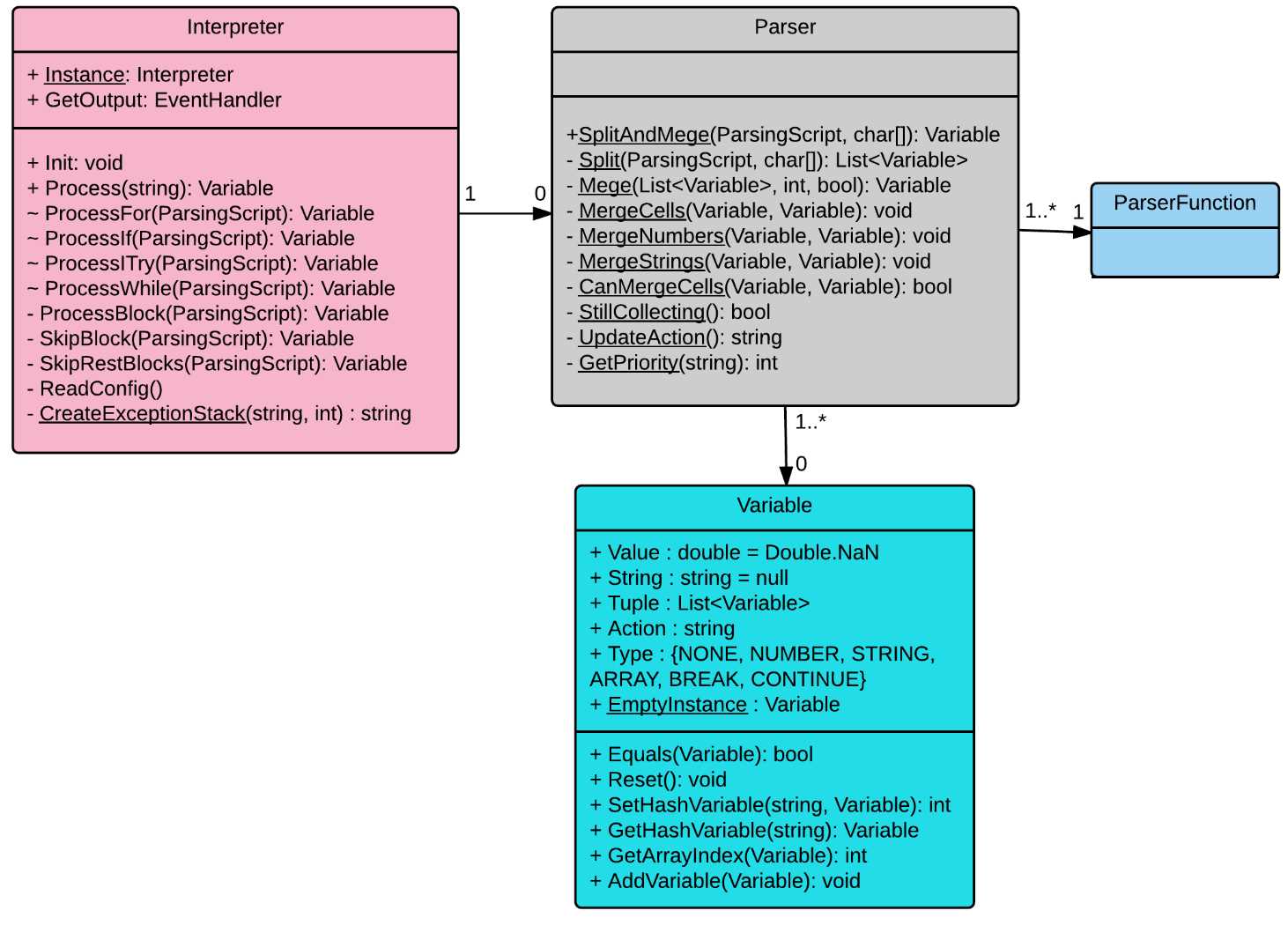

Next we show the URL diagrams of the parser classes that we have seen so far, and that we are going to see in the rest of this book. Figure 3 contains the overall structure of the main classes used.

Figure 3: Overall structure of parser classes

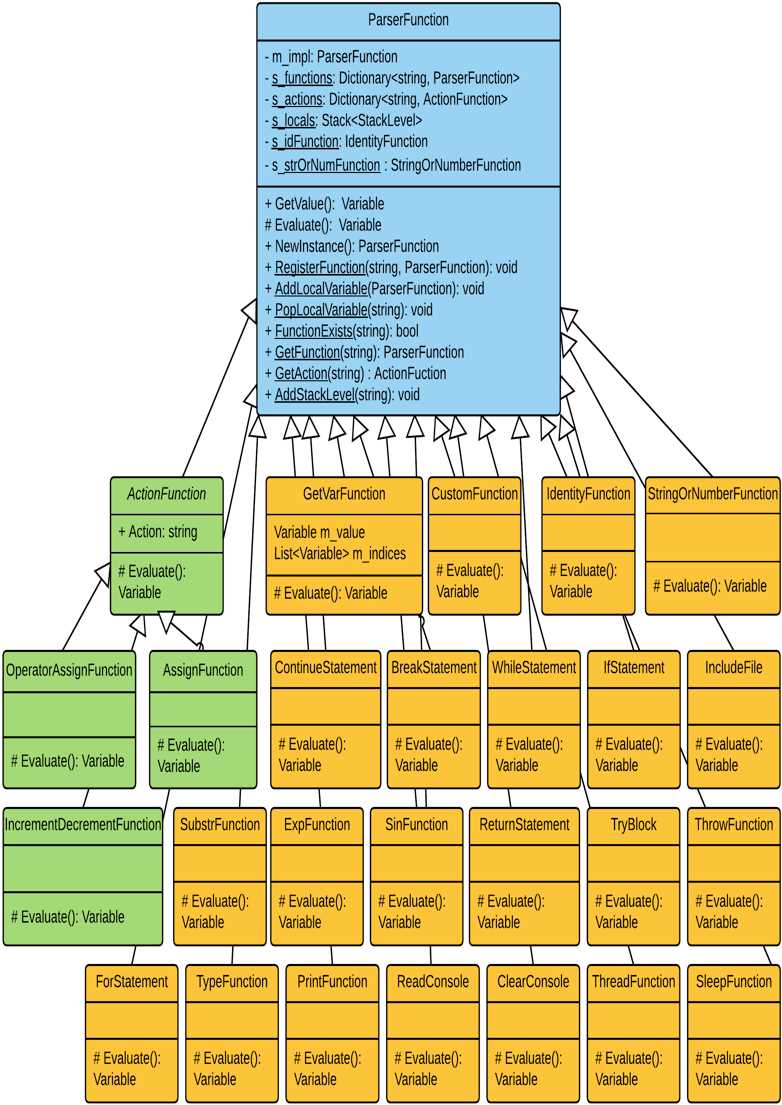

Figure 4 contains the ParserFunction class and all the classes deriving from it. It’s not complete since the number of descendants can be virtually limitless; for example, all possible mathematical functions, like power, round, logarithm, cosine, and so on, belong all there as well. In order to add a new functionality to the parser, you extend the ParserFunction class, and the new class will belong to the Figure 4.

Figure 4: The ParserFunction class and its descendants

Conclusion

In this chapter we implemented some of the basic control flow statements. We implemented all of them as functions, using the Split-and-Merge algorithm developed in the previous chapter.

In the next chapter we are going to add some more power to our language, implementing different functions.

- 1800+ high-performance UI components.

- Includes popular controls such as Grid, Chart, Scheduler, and more.

- 24x5 unlimited support by developers.