CHAPTER 4

Imperative and Functional Interaction

This section will discuss how to work with C# and F# code together in one application. We’ll create a simple application that has a front-end user interface implemented in C# and its back-end data management implemented in F#. Whether creating Windows Forms or web applications with ASP.NET, mixing both imperative and functional programming styles is probably going to be the most efficient approach—certainly, the tools for designing forms or web pages, XAML or HTML, all have considerably more support for generating C# or VB code. Furthermore, because UIs are constantly managing state, the parts of an application that are intrinsically mutable are quite frankly best implemented in a language that is designed to support mutability. Conversely, the back-end of an application dealing with data persistence and transformation is often well-suited for F#, as immutability is critical for working with asynchronous processes.

Creating multi-language projects

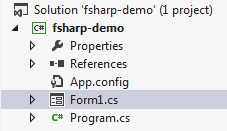

The first step is simple enough: create a new Windows Forms Application project in Visual Studio 2012. I’ve called mine fsharp-demo:

- New Windows Forms Project

Next, right-click on the solution and select Add > New Project. On the left tree, click Other Languages to expand the selection list:

- Available Programming Languages

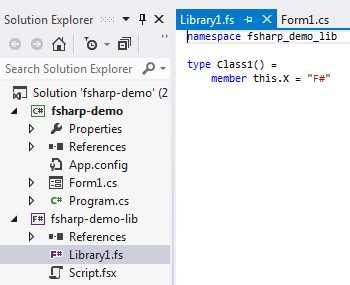

Click Visual F# and select F# Library. Enter a name, for example, fsharp-demo-lib. Note how Visual Studio creates a stub .fs file with a default class:

- New F# Library

Calling F# from C#

Unfortunately, the code generated in this example is not really what we want—Visual Studio has created an imperative-style class template for us in F#, when what we want is a functional programming template. So, replace the generated code first with a module name. We do this because let statements, which are static, require a module that is implemented by the compiler as a static class. So instead, we can write, for example:

module FSharpLib let Add x y = x + y |

We got rid of the stub class as well, and created a simple function that we can call from C#. If you leave off the module name, the module name will default to the name of the file, which in our case would be Library1.

If you need to use a namespace to avoid naming conflicts, you can do so like this:

namespace fsharp_demo_lib module FSharpLib = let Add x y = x + y |

Note that the = operator is now explicitly required. This is because when combined with a namespace, the module is now local within that namespace rather than top-level.[61] In the C# code, we have to add a using fsharp_demo_lib; statement or reference the namespace explicitly when resolving the function call, for example fsharp_demo_lib.FSharpLib.Add(1, 2);. For the remainder of this section, I will not be using namespaces in F#.

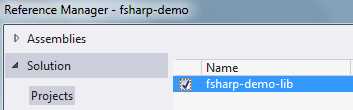

Next, you’ll want to add a reference in your C# project to the F# project:

- Referencing the C# Project

Now you will notice something interesting—if you go to Form1.cs and type the following:

public Form1() { int result = FSharpLib.Add(1, 2); // <<== start typing this InitializeComponent(); } |

You will notice that the IDE flags this as an unknown class and IntelliSense does not work. You always need to build the solution when making changes in the F# code before those changes will be discovered by the IDE on the C# side.

Finish the test case in the constructor:

public Form1() { int result = FSharpLib.Add(1, 2); MessageBox.Show("1 + 2 = " + result); InitializeComponent(); } |

When we run the application, a message box first appears with the result. Congratulations, we’ve successfully called F# from C#.

Calling C# from F#

We may also want to go the other direction, calling C# from our F# code. We’ve already seen numerous examples of this, but let’s say you want to call some C# code in your own application. As with any multi-project solution, we can’t have circular references, so this means that you have to be cognizant of the structure of your solution, such that common code shared between C# and F# projects must go in its own project.

The next question is whether you want to call C# code in a static or instance context. A static context is similar to calling F# code. First, simply create a static class and some static members:

namespace csharp_demo_lib { public static class StaticClass { public static void Print(int x, int y) { MessageBox.Show("Static call, x = " + x + " y = " + y); } } } |

And in the F# code, we add a reference to the C# library and use the open keyword (equivalent to the using keyword in C#) to reference the namespace:

module FSharpLib open csharp_demo_lib let Add x y = StaticClass.Print(x, y) x + y |

Conversely, we can instantiate a C# class and manipulate its members in a mutable context, as well as call methods. For example:

namespace csharp_demo_lib { public class InstanceClass { public void Print() { MessageBox.Show("Instance Call"); } } } |

And in F#:

module FSharpLib open csharp_demo_lib let Add x y = let inst = new InstanceClass() inst.Print() StaticClass.Print(x, y) x + y |

Database explorer—a simple project

Now that we understand the basics of C# and F# interaction, let’s create a simple “database explorer” application. This application will utilize Syncfusion’s Essential Studio as the front-end in C#, and F# as the back-end for all the database connections and queries. This user interface will consist of:

- A list control from which the user can pick a table.

- A grid control that will display the contents of the selected table.

The back-end, in F#, will:

- Query the database schema for a list of tables.

- Query the database for selected table data.

We’ll be connecting to the AdventureWorks2008 database.

The source code can be viewed and cloned from GitHub at https://github.com/cliftonm/DatabaseExplorer.

The back-end

Let’s start by writing the F# back-end and incorporate some simple unit tests[62] (written in F#!) using xUnit[63] in a test-driven development[64] process, as this also illustrates how to write unit tests for F#. We’re using xUnit instead of nUnit because, at the time of this writing, nUnit does not support .NET 4.5 assemblies, whereas the xunit.gui.clr4.exe test runner does.

Establishing a connection

We’ll start with a unit test that verifies that a connection is established to our database, and if we give it a bad connection string, we get a SqlException:

module UnitTests open System.Data open System.Data.SqlClient open Xunit open BackEnd type BackEndUnitTests() = [<Fact>] member s.CreateConnection() = let conn = openConnection "data source=localhost;initial catalog=AdventureWorks2008;integrated security=SSPI" Assert.NotNull(conn); [<Fact>] member s.BadConnection() = Assert.Throws<SqlException>(fun () -> BackEnd.openConnection("data source=localhost;initial catalog=NoDatabase;integrated security=SSPI") |> ignore) |

Note that we have to explicitly pipe the result of a function that returns something to “ignore.”

The supporting F# code:

module BackEnd open System.Data open System.Data.SqlClient // Opens a SqlConnection instance given the full connection string. let openConnection connectionString = let connection = new SqlConnection() connection.ConnectionString <- connectionString connection.Open() connection |

Loading the database schema

Next, we’ll load the database schema. When interfacing C# and F# code, it is a good practice to stay within the F# namespaces and constructs as much as possible, writing separate functions to convert from F# constructs to the imperative (mutable) structures that C# typically uses. First, let’s write a simple unit test that ensures we get some results:

[<Fact>] member s.ReadSchema() = use conn = s.CreateConnection() let tables = BackEnd.getTables conn Assert.True(tables.Length > 0) // Verify that some known table exists in the list. Assert.True(List.exists(fun (t) -> (t.tableName = "Person.Person")) tables) |

Note the use keyword,[65] which will automatically call Dispose when the variable goes out of scope.

The supporting F# code follows. Note that one of the best practices in writing F# code is to write functions as small as possible and extract behaviors into separate functions:

// A simple record for holding table names. type TableName = {tableName : string} // A discriminated union for the types of queries we're going to use. type Queries = | LoadUserTables // Returns a SQL statement for the desired query. let getSqlQuery query = match query with | LoadUserTables -> "select s.name + '.' + o.name as table_name from sys.objects o left join sys.schemas s on s.schema_id = o.schema_id where type_desc = 'USER_TABLE'" // Returns a SqlCommand instance. let getCommand (conn : SqlConnection) query = let cmd = conn.CreateCommand() cmd.CommandText <- getSqlQuery query cmd

// Reads all records. let readTableNames (cmd : SqlCommand) = let rec read (reader : SqlDataReader) list = match reader.Read() with | true -> read reader ({tableName = (reader.[0]).ToString()} :: list) | false -> list use reader = cmd.ExecuteReader() read reader [] // Returns the list of tables in the database specified by the connection. let getTables (conn : SqlConnection) = getCommand conn LoadUserTables |> readTableNames |> List.rev |

In the previous code, we’ve created:

- A discriminated union so we can have a lookup table for our SQL statements.

- A function that returns the desired SQL statement given the desired type. This could be easily replaced with, say, a lookup from an XML file.

- A function for returning a SqlCommand instance given a connection and the query name.

- A function that implements a recursive reader.

- The getTables function, which returns a list of table names.

Before we conclude with the reading of the database’s user tables, let’s write a function that maps the F# list to a System.Collections.Generic.List<string>, suitable for consumption by C#. Again, we could use the F# types directly in C# by including the FSharp.Core assembly. This conversion is done here merely as a matter of convenience. Here’s a simple unit test:

[<Fact>] member s.toGenericList() = use conn = s.CreateConnection() let tables = BackEnd.getTables conn let genericList = BackEnd.tableListToGenericList tables Assert.Equal(genericList.Count, tables.Length) Assert.True(genericList.[0] = tables.[0].tableName) |

And here’s the implementation:

// Convert a TableName : list to a System.Collection.Generic.List. let tableListToGenericList list = let genericList = new System.Collections.Generic.List<string>() List.iter(fun (e) -> genericList.Add(e.tableName)) list genericList |

Reading a table’s data

Next, we want to be able to read any table’s data, returning a tuple of the data itself as a list of generic records and a list of column names. The following example is our unit test:

[<Fact>] member s.LoadTable() = use conn = s.CreateConnection() let data = BackEnd.loadData conn "Person.Person" Assert.True((fst data).Length > 0) // Assert something we know about the schema. Assert.True(List.exists(fun (t) -> (t.columnName = "FirstName")) (snd data)) // Verify the correct order of the schema. Assert.True((snd data).[0].columnName = "BusinessEntityID"); |

To implement this, we now need to extend our SQL query lookup:

type Queries = | LoadUserTables | LoadTableData | LoadTableSchema |

Also, the function that returns the query needs to be smarter, substituting table name for certain queries based on an optional table name parameter:

let getSqlQuery query (tableName : string option) = match query with | LoadUserTables -> "select s.name + '.' + o.name as table_name from sys.objects o left join sys.schemas s on s.schema_id = o.schema_id where type_desc = 'USER_TABLE'" | LoadTableData -> match tableName with | Some name -> "select * from " + name | None -> failwith "table name is required." | LoadTableSchema -> match tableName with | Some name -> let schemaAndName = name.Split('.') "select COLUMN_NAME from information_schema.columns where table_name = '" + schemaAndName.[1] + "' AND table_schema='" + schemaAndName.[0] + "' order by ORDINAL_POSITION" | None -> failwith "table name is required." |

Next we need to be able to read the table data:

// Returns all the fields for a record. let getFieldValues (reader : SqlDataReader) = let objects = Array.create reader.FieldCount (new Object()) reader.GetValues(objects) |> ignore Array.toList objects // Returns a list of rows populated with an array of field values. let readTableData (cmd : SqlCommand) = let rec read (reader : SqlDataReader) list = match reader.Read() with | true -> read reader (getFieldValues reader :: list) | false -> list use reader = cmd.ExecuteReader() read reader [] |

And we need to be able to read the schema for the table (note the required explicit casting to an Object[]):

let readTableSchema (cmd : SqlCommand) = let schema = readTableData cmd List.map(fun (c) -> {columnName = (c : Object[]).[0].ToString()}) schema |> List.rev |

And lastly, we have the function that loads the data, returning a tuple of the data and its schema:

let loadData (conn : SqlConnection) tableName = let data = getCommand conn LoadTableData (Some tableName) |> readTableData let schema = (getCommand conn LoadTableSchema (Some tableName) |> readTableSchema) (data, schema) |

Now, if you were paying attention, you’ll have noticed that the functions readTableNames and readTableData are almost identical. The only difference is how the list is constructed. Let’s refactor this into a single reader in which we pass in the desired function for parsing each row to create the final list:

// Reads all the records and parses them as specified by the rowParser parameter. let readData rowParser (cmd : SqlCommand) = let rec read (reader : SqlDataReader) list = match reader.Read() with | true -> read reader (rowParser reader :: list) | false -> list use reader = cmd.ExecuteReader() read reader [] |

We now have a more general-purpose function that allows us to specify how we want to parse a row. We now create a function for returning a TableName record:

// Returns a table name from the current reader position. let getTableNameRecord (reader : SqlDataReader) = {tableName = (reader.[0]).ToString()} |

This allows us to refactor getTables:

// Returns the list of tables in the database specified by the connection. let getTables (conn : SqlConnection) = getCommand conn LoadUserTables None |> readData getTableNameRecord |

And we also refactor reading the table schema and the table’s records:

// Returns a list of ColumnName records representing the field names of a table. let readTableSchema (cmd : SqlCommand) = let schema = readData getFieldValues cmd List.map(fun (c) -> {columnName = (c : List<Object>).[0].ToString()}) schema |> List.rev // Returns a tuple of table data and the table schema. let loadData (conn : SqlConnection) tableName = let data = getCommand conn LoadTableData (Some tableName) |> readData getFieldValues let schema = (getCommand conn LoadTableSchema (Some tableName) |> readTableSchema) (data, schema) |

Here we are taking advantage of partial function application—we’ve easily refactored the reader to be more general purpose in parsing each row. This took about five minutes to do, and with our existing unit tests we were able to verify that our changes didn’t break anything.

Converting our F# structures to a DataTable

Unless you want to include the FSharp.Core assembly in your C# project, you’ll want to convert anything being returned to C# into .NET “imperative-style” classes. It simply makes things easier. And certainly, we could have loaded the records directly into a DataTable by going through a DataSet reader, but the process we used was more illustrative of keeping things “native” to F# (and besides, one usually wouldn’t load up the entire table, but rather implement a pagination scheme of some sort.)

So, the final step is to populate a DataTable with our F# rows and table schema information, which we’ll do in F#. First though, we should create a unit test that ensures some things about our DataTable:

[<Fact>] member s.ToDataTable() = use conn = s.CreateConnection() let data = BackEnd.loadData conn "Person.Person" let dataTable = BackEnd.toDataTable data Assert.IsType<DataTable>(dataTable) |> ignore Assert.Equal(dataTable.Columns.Count, (snd data).Length) Assert.True(dataTable.Columns.[0].ColumnName = "BusinessEntityID") Assert.Equal(dataTable.Rows.Count, (fst data).Length) |

The implementation in F# involves three functions: setting up the columns, populating the rows, and a function that calls both of those steps and returns a DataTable instance:

// Populates a DataTable given a ColumnName List, returning // the DataTable instance. let setupColumns (dataTable : DataTable) schema = let rec addColumn colList = match colList with | hd::tl -> let newColumn = new DataColumn() newColumn.ColumnName <- hd.columnName dataTable.Columns.Add(newColumn) addColumn tl | [] -> dataTable addColumn schema // Populates the rows of a DataTable from a data list. let setupRows data (dataTable : DataTable) = // Rows: let rec addRow dataList = match dataList with | hd::tl -> let dataRow = dataTable.NewRow() // Columns: let rec addFieldValue (index : int) fieldList = match fieldList with | fhd::ftl -> dataRow.[index] <- fhd addFieldValue (index + 1) ftl | [] -> () addFieldValue 0 hd dataTable.Rows.InsertAt(dataRow, 0) addRow tl | [] -> dataTable addRow data // Return a DataTable populated from our (data, schema) tuple. let toDataTable (data, schema) = let dataTable = new DataTable() setupColumns dataTable schema |> setupRows data |

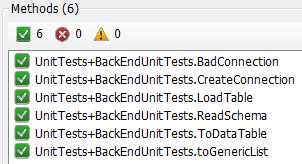

All our unit tests pass!

- Successful Unit Tests

The front-end

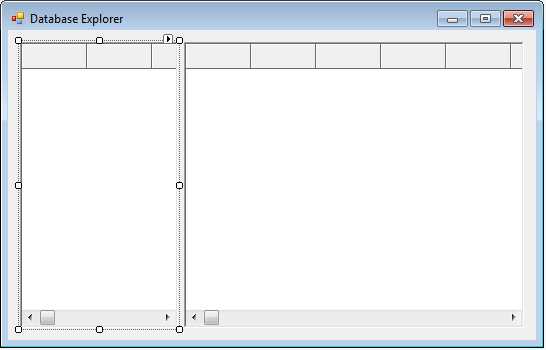

Now we’re ready to write the front-end. We’ll create a simple layout of two GridListControl controls:

- Two GridList Controls

The code-behind consists of loading the list of tables, calling our F# code to get the table list:

protected void InitializeTableList() { List<string> tableList; using (var conn = BackEnd.openConnection(connectionString)) { tableList = BackEnd.getTablesAsGenericList(conn); } var tableNameList = new List<TableName>(); tableList.ForEach(t => tableNameList.Add(new TableName() { Name = t })); gridTableList.DisplayMember = "Name"; gridTableList.ValueMember = "Name"; gridTableList.DataSource = tableNameList; } |

When a table is selected, we get the DataTable from our F# code and set the grid’s DataSource property.

private void gridTableList_SelectedValueChanged(object sender, EventArgs e) { if (gridTableList.SelectedValue != null) { string tableName = gridTableList.SelectedValue.ToString(); DataTable dt; using (var conn = BackEnd.openConnection(connectionString)) { Cursor = Cursors.WaitCursor; var data = BackEnd.loadData(conn, tableName); dt = BackEnd.toDataTable(data.Item1, data.Item2); Cursor = Cursors.Arrow; } gridTableData.DataSource = dt; } } |

This gives us a nice separation between the front-end user interface processes and the back-end database interaction, resulting in a simple database navigator.

- Complete Database Navigator

- 1800+ high-performance UI components.

- Includes popular controls such as Grid, Chart, Scheduler, and more.

- 24x5 unlimited support by developers.