CHAPTER 1

Digital Reality Introduction

I had my first experience with virtual reality (VR) as a teenager, in 1993. I remember it very accurately, as it completely blew my mind. It was the game Dactyl Nightmare, and it was amazing. Looking at it today, it was a bunch of 8-bit blocks, some platforms, and a very uncomfortable headset you had to wear. I didn’t care, though. That early experience of immersive computing has stayed with me since, and as the world is now entering a new era of virtual and augmented reality.

We have come a long way since 1993, and VR has developed into many shapes and forms. We now have augmented reality (AR) devices that overlay data on your physical world as viewed through your phone. VR devices are now much more accessible, such as the Oculus Rift, and there are devices that fit in neither or both categories, such as Microsoft’s HoloLens, which exists in mixed reality (MR). In order to describe this whole segment of technology, regardless of what kind of reality, I have coined the term digital reality (no abbreviation though).

When discussing digital reality, it is important to understand the various segments, such as VR, AR, and MR. Not only is it important to know in which segment a potential project would fall, but you also want to target the right device with the right idea. For example, why create an experience for a $3,000 device that few people have access to, when the idea could work equally well on a $300 device, such as a smartphone? Understanding not only the development platform you are targeting, but also the users of this platform, as well as the other platforms in the same segment, is essential to creating a powerful and immersive experience that those users will buy into.

With that in mind, let’s go through each digital reality segment to understand exactly where HoloLens applications fit in. As the following figure shows, digital reality has three main, defined areas: virtual, augmented, and mixed.

Figure 1: The Main Categories within Digital Reality

Virtual reality

Most people have heard the term virtual reality and associate it with either some form of gaming or a gimmick. The general public, and to some extent IT professionals, see it very much as the “flavor of the month” and pay it little attention. The truth is that VR was a billion-dollar industry in 2016[1] and is predicted to be a $150 billion industry by 2020.[2] It is a huge market, and the possibilities and opportunities will only get better and more elaborate.

Note: The first references to the concept of virtual reality came from science fiction. Stanley G. Weinbaum's 1935 short story "Pygmalion's Spectacles" describes a goggle-based virtual reality system with holographic recording of fictional experiences, including smell and touch.

The defining feature of VR is a complete virtual world created by the developer for the user. Every single component of the reality is virtual, and the user is removed from the physical reality they are in. This makes the experience incredibly immersive, as the developer is in control of the entire experience. It also means that developers must pay a lot of attention to all the little details. Managing motion sickness can be a real problem.

Figure 2: Oculus Rift VR Headset by Ats Kurvet (CC BY-SA 4.0)

Another limitation with VR is that the user can’t physically move, because their entire reality has been replaced. Users moving about and crashing into objects is not a good look, so movement in VR experiences is generally done with handheld triggers. The movement must be simulated, and again, this leads back to managing motion sickness. If you make the movement too realistic, chances are you’ll need a bucket for the user to throw up in. If you make it not realistic enough, users won’t buy into the world you have created.

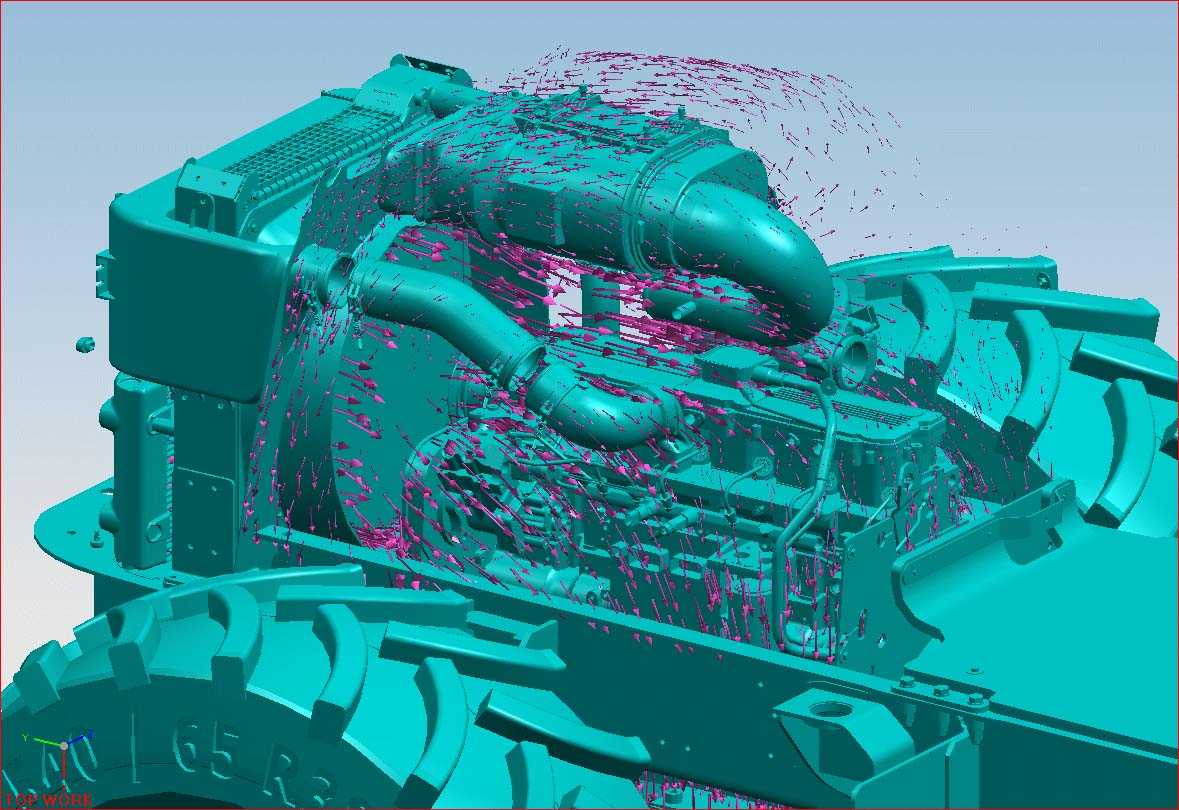

One strength of VR is the prototyping capabilities for scenarios that would be either expensive or dangerous to put inexperienced users through. Major motor manufacturing companies have been using VR for a long time to design and engineer their vehicles before having produced a single physical nut or bolt. You can also place users in locations they would never have dreamt of, such as in the center of the Melbourne Cricket Ground with 90,000 spectators.

VR is here to stay, no doubt about it. The technology has changed the landscape of digital reality, and it has come a long way from the early 90s and my first experience with it. More and more devices are being brought to market and the experiences are becoming more elaborate and immersive. Yet, by the sheer nature of blocking out the physical world, the VR experiences are limited in their reach. Although the applications will break boundaries and change the way software is viewed, VR does not cover every aspect of the digital reality space.

Figure 3: Engine Airflow Simulation (Screenshot of UGS NX 5, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Augmented reality

Whereas VR often requires dedicated hardware, AR can utilize any smartphone or tablet most of the time. It is a live direct or indirect view of a physical, real-world environment whose elements are augmented by computer-generated sensory input such as sound, video, graphics, or GPS data. Augmented reality experiences overlay data onto the physical experience, and thus enhance it (or at least, that’s the idea).

Because the reality is an augmentation of the real world, experiences are often delivered through smaller handheld devices. When you’re looking through this device, most commonly by using the camera and screen, the experience changes how you see the real world. This makes the technology very accessible for most people, and it’s used in a large range of different ideas, from business cards that come to life to seeing through real walls in imaginary places.

Figure 4: The Augmented Reality Game Pokemon Go (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Note: Pokemon Go is one of the most successful and popular augmented reality experiences.

Generally, AR experiences need a trigger point, which is a visual clue that will start the experience. Because this trigger point relies on a specific outline or figure, the experience is very limited and can’t work just anywhere. That isn’t to say that it doesn’t enhance the user’s world, but the limited “view” into the augmented reality combined with the trigger point makes for a sometimes clunky experience.

Mixed reality

The last digital reality we’ll go through actually fits in between the first two. It’s the newest, it is a combination of the first two to some extent, and it is the focus of this book. A term invented by Microsoft in conjunction with launching HoloLens, mixed reality (MR) is exactly what it sounds like: a mix of digital and real-world objects you can interact with in more-or-less natural ways. In a way, mixed reality is the best of both virtual and augmented realities, but it’s also more complex. On the one hand, you can place any hologram you like in the real world, but then you also have to manage this hologram in both a digital reality and a physical reality.

Table 1: Digital Reality Comparison

Augmented Reality | Mixed Reality | Virtual Reality | |

|---|---|---|---|

Real world augmentation | ü | ü | |

Interactive Holograms | ü | ||

Virtual world experience | ü | ü | |

Replaces real world | ü |

Genuine holographic experiences

Because of the futuristic connotations of placing and interacting with holograms in your physical space, designing and developing a true mixed-reality experience comes with its own set of pitfalls. It is easy to get caught up in the “wow” of the device and the capability, but often that results in either an experience that is lacking in longevity or an experience that is not uniquely mixed reality. Building apps that take over the entire reality are often better off being built as full-on VR apps, and apps that have a limited use case and simple “trigger and event” could be done with a smartphone as an AR app.

When designing for mixed reality, there has to be interaction between the holograms and the physical world. For example, you might make characters sit on the couch next to you, have robots enter the room through the actual walls, or create holograms sized to fit in whatever physical space they are placed in. If you place a holographic ball on a table, it should roll off if the table is moved.

HoloLens

The first commercially available mixed-reality device is the HoloLens from Microsoft. It is a device many years in the making, and it has managed to push the boundaries for digital reality, even in its prototype state. The HoloLens is a fully self-contained computer with bespoke hardware, such as the Holographic Processing Unit (HPU), which is in charge of calculating all of the 3D spatial computation in relation to holograms. The main difference, and distinct advantage, from other digital reality devices is that the HoloLens is untethered. There is no additional computing device required to run the mixed reality experience, which means the user is completely free to move about their environment. This is incredibly important, as the device is aware of its surroundings and physical position.

If you place a hologram—be it on a wall, on a table, or floating in midair—it stays there pretty much forever until it’s removed. Holograms persist in relation to the real world around them, and this is part of the experience. You can place a flat 2D hologram, such as a video clip, on a wall, walk to the next room, and when you come back it will be exactly where you left it. This is what the mixed reality experience is all about: a complete mix between digital and physical realities.

Some of the first demos we are seeing from Microsoft include Minecraft in 3D being placed in a physical space with interaction with 2D devices; a first-person shooter where robots come out of your walls and shoot at you; a full medical representation of the human body to allow medical students to learn about bones, muscles, and the nervous system; and much more. There are so many applications for the HoloLens that the imagination of the developers is the only boundary.

Figure 5: Minecraft on HoloLens (Microsoft Sweden—Win10-HoloLens-Minecraft, CC BY 2.0)

Although the hardware is cutting edge and unlike anything else, we aren’t going to delve into the hardware side of things in this book. We will focus on how to create the mixed reality experiences from a software perspective.

Figure 6: Microsoft HoloLens (Microsoft Sweden—CC BY 2.0)

Spatial mapping

To allow the HoloLens to place holograms on physical surfaces and interact with the real world, spatial mapping is key. To understand how it works, see Chapter 3.

Universal Windows Platform

One of the key features of the HoloLens is that it runs on Windows 10. As amazing and futuristic as the holograms and the mixed reality experiences are, the fact that the device runs the latest Microsoft operating system means the device is also running the Universal Windows Platform (UWP). All Windows 10 devices—from Xbox, to PC, to HoloLens—conform to the contract with developers that is the UWP. This has great advantages, and not just for developers.

Developers

The UWP brings a common set of APIs and tools to creating apps for any device on the Windows 10 platform. As we will see in the next chapter, the tools are first class, and you can use the typical programming language from the Microsoft stack: C#. Developers can use the same approach to developing for any device that runs on Windows 10. There are of course platform-specific differences within the UWP, but as a base there is a Core API that is guaranteed between platforms.

This core API layer is also the reason it is so easy to publish apps across platforms. You will have to do the work according to each platform, such as managing mobile connections on smartphones, addressing a lack of a physical screen on IoT devices, and handling 3D on HoloLens. For HoloLens specifically, you can also publish 2D apps that will appear as flat apps in a 3D space when used.

Users

Although this book is primarily for developers, let us not forget that we are ultimately writing software for the users. The UWP is a big advantage for users as well. They can easily use the same profile across devices if the developer has set the service up, and users can also download the same app for any device that is supported. If they buy it once, they can download it anywhere.

In general, users don’t care how something works technically, but they do appreciate convenience and ease of use. The UWP creates a seamless experience across any Microsoft device that runs on Windows 10, and the user only logs in once on each device to set it all up. And of course, this works with HoloLens apps as well.

Businesses

For businesses, the return on investment is greatly improved—mainly because of the reuse of code, but also the ease of development from using the same tooling for multiple platforms and form factors. Even the user interface is adaptive and can for the most parts be a single code base that works and conforms to the available screen space and platform-specific features.

The business use case is also not the focus of this book, but it is an important part of the decision to build UWP apps, whether they are for HoloLens or another Windows 10 device. Even existing apps that run on Windows 10 can be ported to HoloLens with little work, and businesses can profit on the UWP platform with little investment.

- 1800+ high-performance UI components.

- Includes popular controls such as Grid, Chart, Scheduler, and more.

- 24x5 unlimited support by developers.