CHAPTER 1

Introducing Hive

What is Hive?

Hive is a data warehouse for Big Data. It allows you to take unstructured, variable data in Hadoop, apply a fixed external schema, and query the data with an SQL-like language. Hive abstracts the complexity of writing and running map/reduce jobs in Hadoop, presenting a familiar and accessible interface for Big Data.

Hadoop is the most popular framework for storing and processing very large quantities of data. It runs on a cluster of machines—at the top end of the scale are Hadoop deployments running across thousands of servers, storing petabytes of data. With Hadoop, you query data using jobs that can be broken up into tasks and distributed around the cluster. These map/reduce tasks are powerful, but they are complex, even for simple queries.

Hive is an open source project from Apache that originated at Facebook. It was built to address the problem of making petabytes of data available to data scientists from a variety of technical backgrounds. Instead of training everyone in map/reduce and Java, Scala, or Python, the Facebook team recognized that SQL was already a common skill, so they designed Hive to provide an SQL facade over Hadoop.

Hive is essentially an adaptor between HiveQL, with the Hive Query Language based on SQL and a Hadoop data source. You can submit a query such as SELECT * FROM people to Hive, and it will generate a batch job to process the query. Depending on the source, the job Hive generates could be a map/reduce running over many files in Hadoop or a Java query over HBase tables.

Hive allows you to join across multiple data sources, so that you can write data as well as read it. This means you can run complex queries and persist the results in a simplified format for visualization. Hive can be accessed using a variety clients, making it easy to integrate into your existing technology landscape, and Hive works well with other Big Data technologies such as HBase and Spark.

In this book, we'll learn how Hive works, how to map Hadoop and HBase data in Hive, and how to write complex queries in HiveQL. We'll also look at running custom code inside Hive queries using a variety of languages.

Use cases for Hive

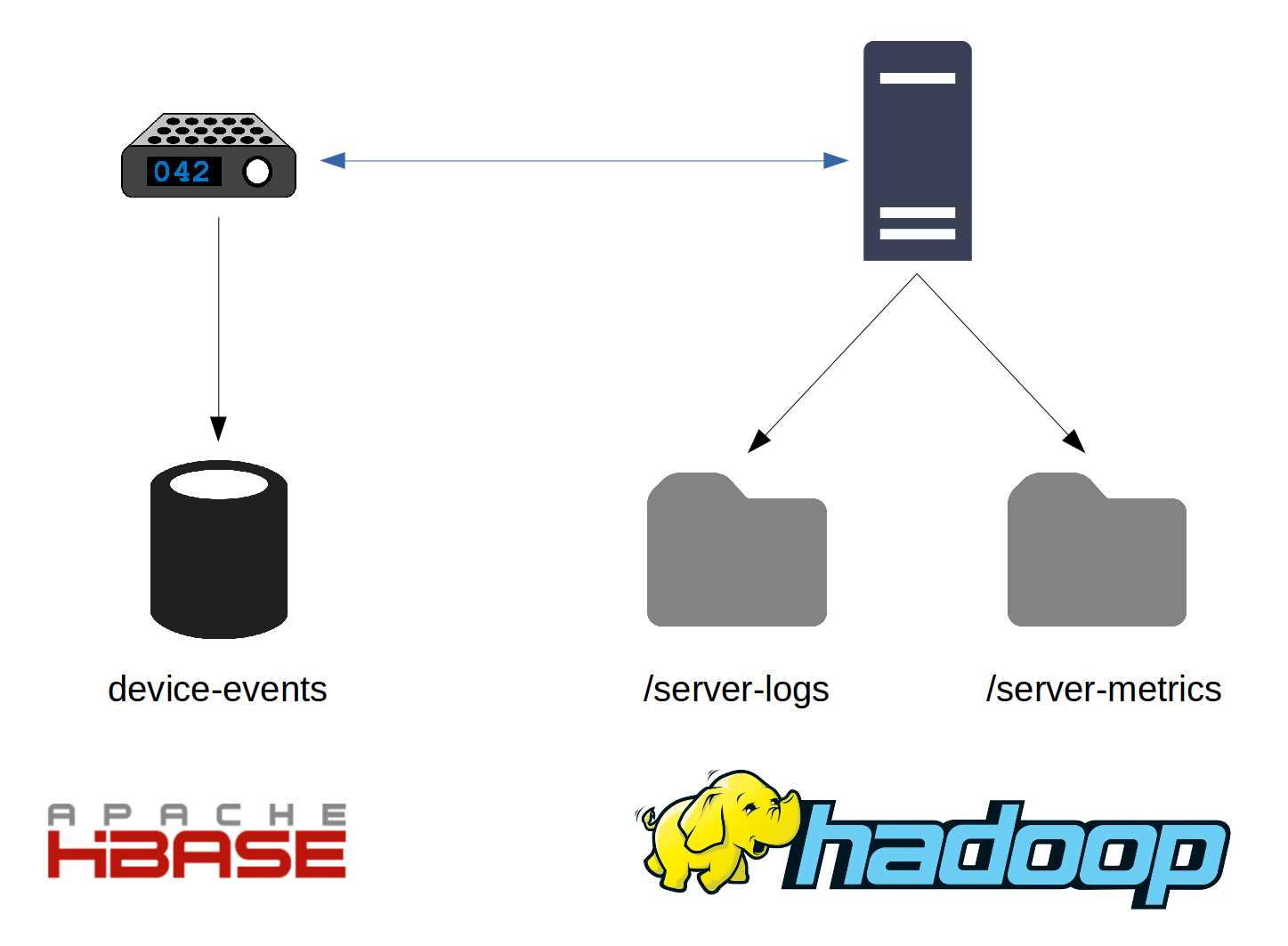

Hive is an SQL facade over Big Data, and it fits with a range of use cases, from mapping specific parts of data that need ad-hoc query capabilities to mapping the entire data space for analysis. Figure 1 shows how data might be stored in an IoT solution in which data from devices is recorded in HBase and server-side metrics and logs are stored in Hadoop.

Figure 1: Big Data Solutions with Multiple Storage Sources

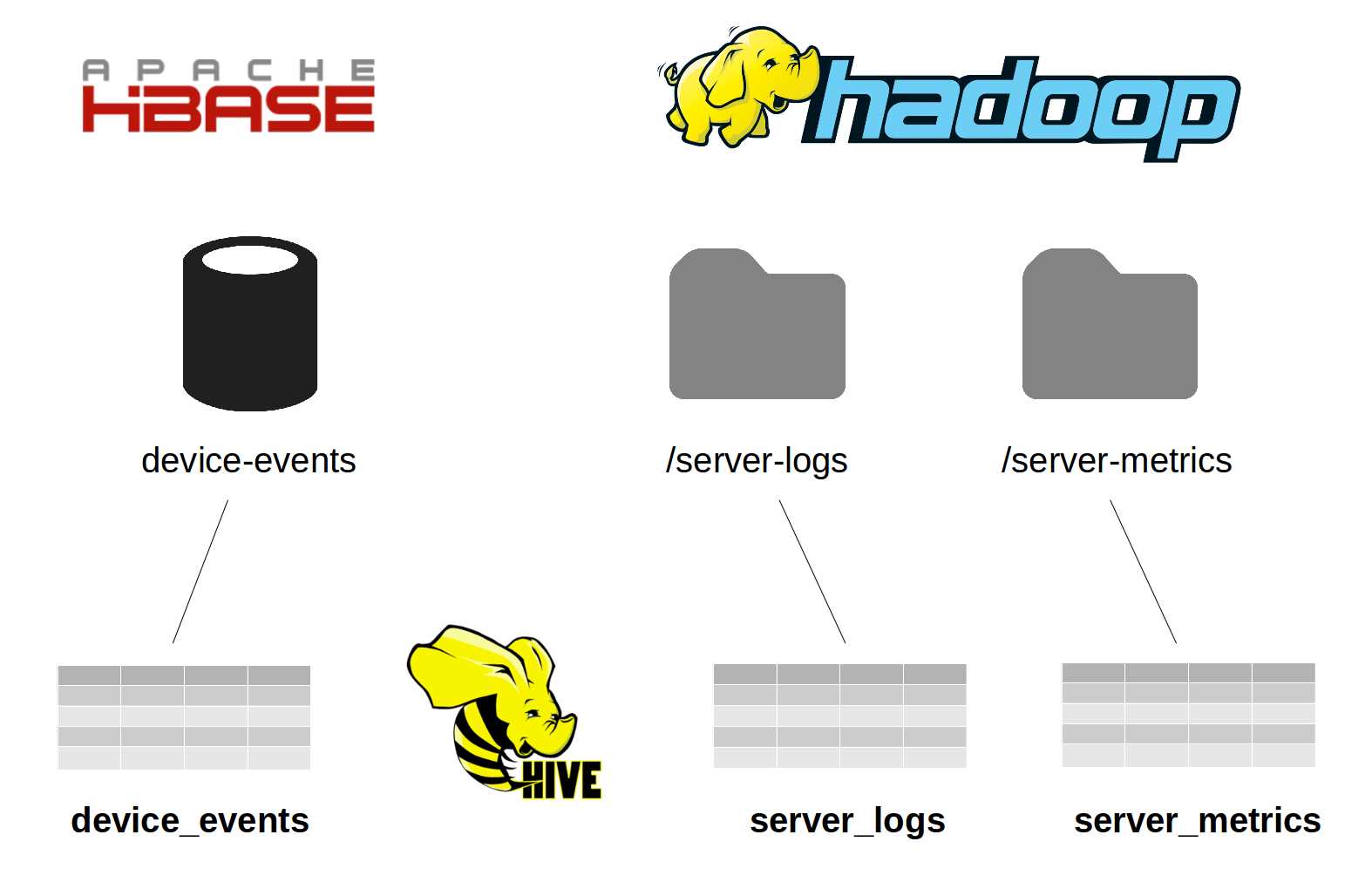

As Figure 2 demonstrates, this space can be mapped as three tables in Hive: device_metrics, server_metrics, and server_logs. Note that although the source folder and table names have hyphens, that isn’t supported in Hive, which means device-events becomes device_events.

Figure 2: Mapping Multiple Sources with Hive

You can find the most active devices for a period by running a group by query over the device_metrics table. In that instance, Hive would use the HBase driver, which provides real-time data access, and you can expect a fast response.

If you want to correlate server errors with CPU usage, you can JOIN across the server_metrics and server_logs tables. Log entries can be stored in a tab-separated variable (TSV) format, and metrics might be in JSON, but Hive will abstract those formats, enabling you to query them in the same way. These files are stored in the Hadoop Distributed File System (HDFS), which means Hive will run them as a map/reduce job.

Hive doesn't only abstract the format of the data, it also abstracts the storage engine, which means you can query across multiple data stores. If you have a list of all known device IDs in a CSV file, you can upload that to HDFS and write an outer join query over the device_metrics HBase table and the device_ids CSV file in order to find devices that have not sent any metrics for a period.

We'll look more closely at running those types of queries in Chapter 9 Querying with HiveQL.

Hive typically runs on an existing Hadoop, HBase, or Spark cluster, which means you don't need additional infrastructure to support it. Instead, it provides another way to run jobs on your existing machines.

Hive’s metastore, which is the database Hive uses to store table definitions separately from the data sources it maps, constitutes its only significant overhead. However, the metastore can be an embedded database, which means running Hive to expose a small selection of tables comes at a reasonable cost. You will notice that once Hive is introduced, it simplifies Big Data access significantly, and its use tends to grow.

Hive data model

I've used a lot of terminology from SQL, such as tables and queries, joins, and grouping. HiveQL is mostly SQL-92 compliant, so that most of the Hive concepts are SQL concepts based on modeling data with tables and views.

However, Hive doesn’t support all the constructs available in SQL databases. There are no primary keys or foreign keys, which means you can’t explicitly map data relations in Hive. Hive does support tables, indexes, and views in which tables are an abstraction over the source data, indexes are a performance boost for queries, and views are an abstraction over tables.

The main difference between tables in SQL and Hive comes with how the data is stored and accessed. SQL databases use their own storage engine and store data internally. For example, a table in a MySQL database is stored in the physical files used by that instance of MySQL, while Hive can use multiple data sources.

Hive can manage storage using internal tables, but it can also use tables to map external data sources. The definition you create for external tables tells Hive where to find the data and how to read it, but the data itself is stored and managed by another system.

Internal tables

Internal tables are defined in and physically managed by Hive. When an internal table is queried, Hive executes the query by reading from its own managed storage. We'll see how and where Hive stores the data for internal tables in Chapter 3 Internal Hive Tables.

In order to define an internal table in Hive, we use the standard create table syntax from SQL, specifying the column details—name, data type, and any other relevant properties. Error! Reference source not found. shows a valid statement that will create a table called server_log_summaries.

Code Listing 1: Creating an Internal Table

CREATE TABLE IF NOT EXISTS server_log_summaries ( period STRING, host STRING, logLevel STRING, count INT ) |

This statement creates an internal Hive table we can use to record summaries for our server logs. This way the raw data will be in external HDFS files with a summary table kept in Hive. Because Code Listing 1’s statement is standard SQL, we can run it on either Hive or MySQL.

External tables

External tables are defined in Hive, but they are physically managed outside of Hive. Think of external tables as a logical view of another data source—when we define an external table, Hive records the mapping but does not copy over any of the source data.

When we query an external table, Hive translates the query into the relevant API calls for the data source (map/reduce jobs or HBase calls) and schedules the query as a Hadoop job. When the job finishes, the output is presented in the format specified in the Hive table definition.

External tables are defined with the create external table statement, which has a similar syntax to internal tables. However, Hive must also know where the data lives, how the data is stored, and how rows and columns are delimited. Code Listing 2 shows a statement that will create an external table over HDFS files.

Code Listing 2: Creating an External Table

CREATE EXTERNAL TABLE server_logs ( serverId STRING, loggedAt BIGINT, logLevel STRING, message STRING ) STORED AS TEXTFILE LOCATION '/server-logs'; |

This statement would fail in a standard SQL database because of the additional properties we give Hive to set up the mapping:

- EXTERNAL TABLE—specifies that the data is stored outside of Hive.

- STORED AS TEXTFILE—indicates the format of the external data.

- LOCATION—shows folder location in HDFS where the data is actually stored.

Hive will assume by default that text files are delimited format, using ASCII character \001 (ctrl-A) as the field delimiter and the new line character as the row delimiter. And, as we'll see in Chapter 3 Internal Hive Tables, we can explicitly specify which delimiter characters to use (e.g., CSV and TSV formats)

When we query the data, Hive will map each line in the file as a row in the table, and for each line it will map the fields in order. In the first field it will expect a string as the serverId value, and in the next field it will expect a long for the timestamp.

Mapping in Hive is robust, which means any blank fields in the source will be surfaced as NULL in the row. Any additional data after the mapped fields will be ignored. Rows with invalid data—incomplete number of fields or invalid field formats—will be returned when you query the table, but only fields that can be mapped will be populated.

Views

Views in Hive work in exactly the same way as views in an SQL database—they provide a projection over tables in order to give a subset of commonly used fields or to expose raw data using a friendlier mapping.

In Hive, views are especially useful for abstracting clients away from the underlying storage of the data. For example, a Hive table can map an HDFS folder of CSV files, and it can offer a view providing access to the table. If all clients use the view to access data, we can change the underlying storage engine and the data structure without affecting the clients (provided we can alter the view and map it from the new structure).

Because views are an abstraction over tables, and because table definitions are where Hive's custom properties are used, the create view statement in Hive is the same as in SQL databases. We specify a name for the view and a select statement in order to provide the data, which can contain functions for changing the format and can join across tables.

Unlike with SQL databases, views in Hive are never materialized. The underlying data is always retained in the original data source—it is not imported into Hive, and views remain static in Hive. If the underlying table structures change after a view is created, the view is not automatically refreshed.

Code Listing 3 creates a view over the server_logs table, where the UNIX timestamp (a long value representing the number of seconds since 1 January 1970) is exposed as a date that can be read using the built-in HiveQL function FROM_UNIXTIME. The log level is mapped with a CASE statement.

Code Listing 3: Creating a View

CREATE VIEW server_logs_formatted AS SELECT serverId, FROM_UNIXTIME(loggedat, 'yyyy-MM-dd'), CASE logLevel WHEN 'F' THEN 'FATAL' WHEN 'E' THEN 'ERROR' WHEN 'W' THEN 'WARN' WHEN 'I' THEN 'INFO' END, message FROM server_logs |

Hive offers various client options for working with the database, including a REST API for submitting queries and an ODBC driver for connecting SQL IDEs or spreadsheets. The easiest option, which we’ll use in this book, is the command line—called Beeline.

Code Listing 4 uses Beeline and shows the same row being fetched from the server_logs table and the server_logs_formatted view, with the view applying functions that make the data friendlier.

Code Listing 4: Reading from Tables and Views using Beeline

> select * from server_logs limit 1; +-----------------------+-----------------------+-----------------------+-- | server_logs.serverid | server_logs.loggedat | server_logs.loglevel | server_logs.message | +-----------------------+-----------------------+-----------------------+-- | SCSVR1 | 1453562878 | W | edbeuydbyuwfu | +-----------------------+-----------------------+-----------------------+-- 1 row selected (0.063 seconds) > select * from server_logs_formatted limit 1; +---------------------------------+----------------------------+----------- | server_logs_formatted.serverid | server_logs_formatted._c1 | server_logs_formatted._c2 | server_logs_formatted.message | +---------------------------------+----------------------------+----------- | SCSVR1 | 2016-01-23 | WARN | edbeuydbyuwfu | +---------------------------------+----------------------------+----------- |

Indexes

Conceptually, Hive indexes are the same as SQL indexes. They provide a fast lookup for data in an existing table, which can significantly improve query performance, and they can be created over internal or external tables, giving us a simple way to index key columns in HDFS or HBase data.

An index in Hive is created as a separate internal table and populated from a map/reduce job that Hive runs when we rebuild the index. There is no automatic background index rebuilding, which means indexes must be rebuilt manually when data has changed.

Surfacing indexes as ordinary tables allows us to query them directly, or we can query the base table and let the Hive compiler find the index and optimize the query.

Code Listing 5 shows an index being created and then populated over the serverId column in the system_logs table (with some of the Beeline output shown).

Code Listing 5: Creating and Populating an Index

> create index ix_server_logs_serverid on table server_logs (serverid) as 'COMPACT' with deferred rebuild; No rows affected (0.138 seconds) > alter index ix_server_logs_serverid on server_logs rebuild; … INFO : The url to track the job: http://localhost:8080/ INFO : Job running in-process (local Hadoop) INFO : 2016-01-25 07:30:48,507 Stage-1 map = 100%, reduce = 100% INFO : Ended Job = job_local1186116405_0001 INFO : Loading data to table default.default__server_logs_ix_server_logs_serverid__ from file:/user/hive/warehouse/default__server_logs_ix_server_logs_serverid__/.hive-staging_hive_2016-01-25_07-30-46_971_7660660875879129827-1/-ext-10000 INFO : Table default.default__server_logs_ix_server_logs_serverid__ stats: [numFiles=1, numRows=3, totalSize=142, rawDataSize=139] No rows affected (1.936 seconds) |

|---|

Although the CREATE INDEX statement is broadly the same as SQL, specifying the table and column name(s) to index, it contains two additional clauses:

- 'COMPACT'—Hive supports a plug-in indexing engine which means we can use COMPACT indexes, suitable for indexing columns with many values, or BITMAP indexes, which are more efficient for columns with a smaller set of repeated values.

- DEFERRED REBUILD—without this, the index will be populated when the CREATE INDEX statement runs. Deferring rebuild means we can populate the index later using the ALTER INDEX … REBUILD statement.

As in SQL databases, indexes can provide a big performance boost, but they do create overhead with the storage used for the index table along with the time and compute required to rebuild the index.

Summary

This chapter’s overview of Hive addressed how the key concepts are borrowed from standard SQL, and it showed how Hive provides an abstraction over Hadoop data by mapping different sources of data as tables that can be further abstracted as views.

We’ve seen some simple HiveQL statements for defining tables, views, and indexes, and we have noted that the query language is based on SQL. HiveQL departs from standard SQL only when Hive needs to support additional functionality, such as when specifying the location of data for an external table.

In the next chapter we’ll begin running Hive and executing queries using HiveQL and the command line.

- 1800+ high-performance UI components.

- Includes popular controls such as Grid, Chart, Scheduler, and more.

- 24x5 unlimited support by developers.