CHAPTER 1

Introducing Hadoop

What is Hadoop?

Hadoop is a Big Data platform with two functions—storing huge amounts of data in safe, reliable storage, and running complex queries over that data in an efficient way. Both storage and compute run on the same set of servers in Hadoop, and both functions are fault tolerant, which means you can build a high-performance cluster from commodity hardware.

Hadoop’s key feature is that it just keeps scaling. As your data needs grow, you can expand your cluster by adding more servers. The same query will run in the exact same way on a cluster with 1,000 nodes as it will on a cluster with five nodes (only much faster).

Hadoop is a free, open source project from Apache. It's been around since 2006, and the last major change to the platform came in 2013. Hadoop is a stable and mature product that has become amazingly popular, and its popularity has only increased as data becomes a core part of every business. Hadoop requires minimal investment to get started, a key feature that allows you to quickly spin up a development Hadoop environment and run some of your own data to see if it works for you.

The other major attraction of Hadoop is its ecosystem. Hadoop itself is a conceptually simple piece of software—it does distributed storage on one hand and distributed compute on the other. But the combination of the two gives us a solid base to work from that other projects have exploited to the full. Hadoop is at the core of a whole host of other Big Data tools, such as HBase for real-time Big Data, Hive for querying Big Data using an SQL-like language, and Oozie for orchestrating and scheduling work.

Hadoop sits at the core of a suite of Big Data tools, and currently trending favorites such as Spark and Nifi still put Hadoop front and center. That means a good understanding of Hadoop will help you get the best out of the other tools you use and, ultimately, get better insight from your data.

We'll learn how Hadoop works, what goes on inside the cluster, how to move data in and out of Hadoop, and how to query it efficiently. Hadoop is primarily a Java platform, and the standard query tool is the Java MapReduce framework. We won’t dive deep into MapReduce, but we will walk through a Java example and also learn how to write the same query in Python and .NET. We’ll explore the commercial distributions of Hadoop and finish with a look at some of the key technologies in the wider Hadoop ecosystem.

Do I have Big Data?

Hadoop may be conceptually simple, but it is nevertheless a complex technology. In order to run it reliably, we need multiple servers dedicated to different roles in the cluster; to work with our data efficiently, we need to think carefully about how it's stored; and to run even simple queries, we need to write a specific program, package it up, and send it to the cluster.

The beauty of Hadoop is that it doesn't get any more complex as our data gets bigger. We’ll simply be applying the same concepts to larger clusters.

If you're considering adopting Hadoop, you must first determine if you really have Big Data. The answer won’t simply be based on how many terabytes of data you have—it's more about the nature of your data landscape. Big Data literature focuses on the three (or four) Vs, and those are a good way of understanding whether or not the benefits of Hadoop will justify its complexity.

Think about your data in terms of the traits shown in Figure 1.

- Volume: how much data do you have?

- Velocity: how quickly do you receive data?

- Variety: does your data come in different forms?

- Veracity: can you trust the content and context of your data?

Having a large amount of data doesn't necessarily mean you have Big Data. If you have 1 TB of log files but the log entries are all in the same format and you're only adding new files at the rate of 1 GB per month, Hadoop might not be a good fit. With careful planning, you could store all that in an SQL database and have real-time query access without the additional overhead of Hadoop.

However, if your log files are highly varied, with a mixture of CSV and JSON files with different fields within the files, and if you're collecting them at a rate of 1 TB per week, you're going to struggle to contain that in SQL, which means Hadoop would be a good fit.

In order to answer whether or not you have Big Data, think about your data in terms of the Vs, then ask yourself, “Can we solve the problems we have using any of our existing technologies?” When the answer is no, it's time to start looking into Hadoop.

The fourth V, veracity, isn't always used, but I think it adds a valuable dimension to our thinking. When we have large volumes of data coming in at high velocity, we need to think about the trustworthiness of the data.

In an Internet of Things (IoT) solution, you may get billions of events coming to you from millions of devices, and you should expect veracity problems. The data from the devices might not be accurate (especially timestamps—clocks on devices are notoriously unreliable), and you might not get the data as expected (events could be dropped or come in the wrong order). That means added complexity for your data analysis.

By looking at your data through the four Vs, you can consider whether or not you have complex storage and compute requirements, and that will help you determine if you need Hadoop.

How Hadoop works

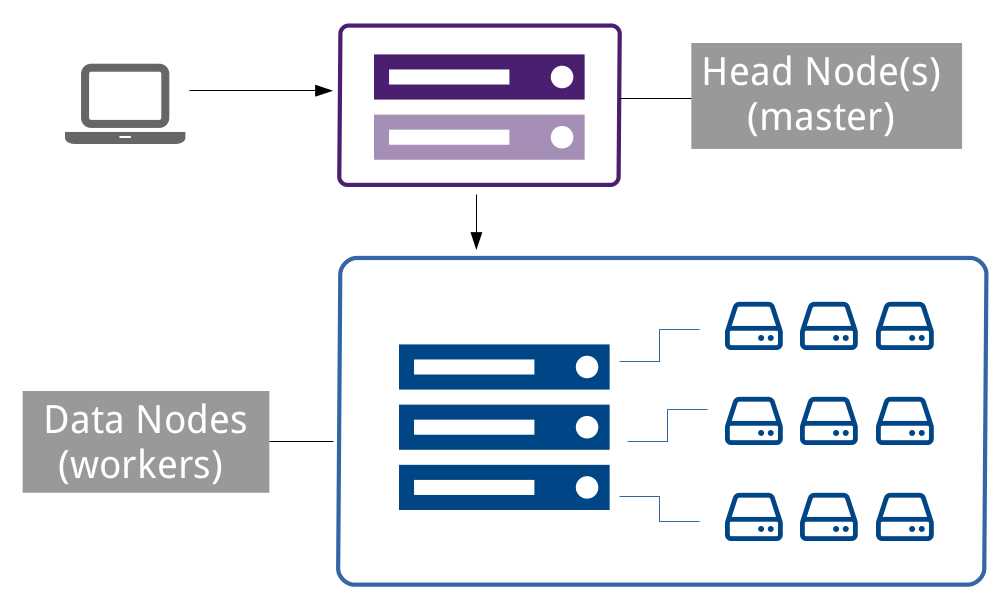

Hadoop is a distributed technology, sharing work among many servers. Broadly speaking, a Hadoop cluster is a classic master/worker architecture, in which the clients primarily make contact with the master, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: The Master/Worker Architecture of Hadoop

The master knows where the data is distributed among the worker nodes, and it also coordinates queries, splitting them into multiple tasks among the worker nodes. The worker nodes store the data and execute tasks sent to them by the master.

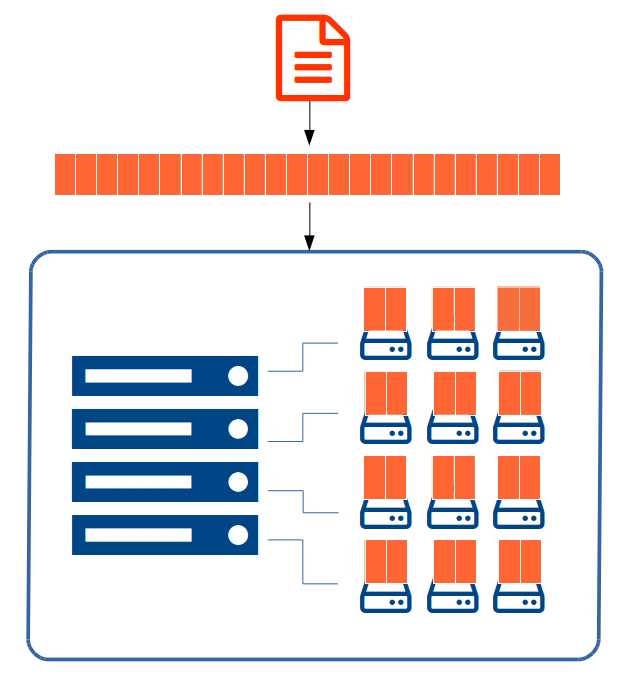

When we store a large file in Hadoop, the file gets split into many pieces, called blocks, and the blocks are shared among the slaves in the cluster. Hadoop stores multiple copies of each block for redundancy at the storage level—by default, three copies of each block are stored. If you store a 1 GB file on your cluster, Hadoop will split it into eight 128 MB blocks, and each of those eight blocks will be replicated on three of the nodes.

That original 1 GB file will actually be stored as 24 blocks of 128 MB, and in a cluster with four data nodes, each node will store six blocks across its disks, as we see in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Large Files Split into File Blocks

Replicating data across many nodes gives Hadoop high availability for storages. In this example, we could lose two data nodes and still be able to read the entire 1 GB file from the remaining nodes. More importantly, replicating the data enables fast query performance. If we have a query that runs over all the data in the file, the master could split that query into eight tasks and distribute the tasks among the data nodes.

Because the master knows which blocks of data are on which servers, it can schedule tasks so that they run on data nodes that have a local copy of the data. This means nodes can execute their tasks by reading from the local disk and save the cost of transferring data over the network. In our example, if the data nodes have sufficient compute power to run two tasks concurrently, our single query over 1 GB of data would be actioned as eight simultaneous tasks, each running more than 128 MB of data.

Hadoop’s ability to split a very large job into many small tasks while those tasks run concurrently is what makes it so powerful—that’s called Massively Parallel Processing (MPP), and it is the basis for querying huge amounts of data and getting the response in a reasonable time.

In order to see how much benefit you get from high concurrency, consider a more realistic example—a query of over 1 TB of data that is split into 256 MB blocks (the block size is one of the many options you can configure in Hadoop). If Hadoop splits that query into 4,096 tasks and the tasks take about 90 seconds each,the query would take more than 100 hours to complete on a single-node machine.

On a powerful 12-node cluster, the same query would complete in 38 minutes. Table 1 shows how those tasks could be scheduled on different cluster sizes.

Table 1: Compute Time for Hadoop Clusters

Data Nodes | Total CPU Cores | Total Concurrent Tasks | Best Compute Time |

1 | 1 | 1 | 100 hours |

12 | 192 | 160 | 38 minutes |

50 | 1200 | 1000 | 6 minutes |

Hadoop aims for maximum utilization of the cluster when scheduling jobs. Each task is allocated to a single CPU core, which means that allowing for some processor overhead, a cluster with 12 data nodes, each with 16 cores, can run 160 tasks concurrently.

A powerful 50-node cluster can run more than 1000 tasks concurrently, completing our 100-hour query in under six minutes. The more nodes you add, however, the more likely it is that a node will be allocated a task for which it does not locally store the data, which means the average task-completion time will be longer, as nodes read data from other nodes across the network. Hadoop does a good job of minimizing the impact of that, as we'll see in Chapter 4 YARN—Yet Another Resource Negotiator.

Summary

This chapter has offered an overview of Hadoop and the concepts of Big Data. Simply having a lot of data doesn't mean you need to use Hadoop, but if you have numerous different types of data that are rapidly multiplying, and if you need to perform complex analytics, Hadoop can be a good fit.

We saw that there are two parts to Hadoop—the distributed file system and the intelligent job scheduler. They work together to provide high availability at the storage level and high parallelism at the compute level, which is how Hadoop enables high-performance Big Data processing without bespoke, enterprise-grade hardware.

Hadoop must understand the nature of the work at hand in order to split and distribute it, which means that in order to query Hadoop, you will need to use set patterns and a specific programming framework. The main pattern is called MapReduce, and map/reduce queries are typically written in Java. In the next chapter, we'll see how to get started with Hadoop and how to write a simple MapReduce program.

- 1800+ high-performance UI components.

- Includes popular controls such as Grid, Chart, Scheduler, and more.

- 24x5 unlimited support by developers.