CHAPTER 3

HDFS—The Hadoop Distributed File System

Introducing HDFS

HDFS is the storage part of the Hadoop platform, and with HDFS you get reliability and scale with commodity hardware.

Commodity is important—it means you don't need specialist hardware in your Hadoop cluster, and nodes don't need to have the same—or even similar—specifications. Many Hadoop installations have started with a cluster built from beg-or-borrow servers and expanded with their own higher-spec machines when the project took off. You can add new nodes to a running cluster while increasing your storage and compute power without any downtime.

The resilience built into HDFS means servers can go offline or disks can fail without loss of data, so that you don't even need RAID storage on your machines. And because Hadoop is much more infrastructure-aware than other compute platforms, you can configure Hadoop to know which rack each server node is on. It uses that knowledge to increase redundancy—by default, data stored in Hadoop is replicated three times in the cluster. On a large cluster with sufficient capacity, Hadoop will ensure one of the replicas is on a different rack from the others.

As far as storage is concerned, HDFS is closed system. When you read or write data in Hadoop, you must do it through the HDFS interface—because of its unique architecture, there's no support for connecting directly to a data node and reading files from its disk. The data is distributed among many data nodes, but the index specifying which file is on which node is stored centrally. In this chapter, we'll get a better understanding of the architecture and see how to work with files in HDFS using the command line.

Architecture of HDFS

HDFS uses a master/slave architecture in which the master is called the “name node” and the slaves are called “data nodes.” Whenever you access data in HDFS, you do so via the name node, which owns the HDFS-equivalent of a file allocation table, called the file system namespace.

In order to write a file in HDFS, you make a PUT call to the name node and it will determine how and where the data will be stored. To read data, you make a GET call to the name node, and it will determine which data nodes get copies of the data and will direct you to read the data from those nodes.

The name node is a logical single point of failure for Hadoop. If the name node is unavailable, you can't access any of the data in HDFS. If the name node is irretrievably lost, your Hadoop journey could be at an end—you'll have a set of data nodes containing vast quantities of data but no name node capable of mapping where the data is, which means it might be impossible to get the cluster operational again and restore data access.

In order to prevent that, Hadoop clusters have a secondary name node that has a replicated file index from the primary name node. The secondary is a passive node—if the primary fails, you’ll need to manually switch to the secondary, which can take tens of minutes. For heavily used clusters in which that downtime is not acceptable, you can also configure the name nodes in a high-availability setup.

Figure 6 shows a typical small-cluster configuration.

For consumers, the Hadoop cluster is a single, large-file store, and the details of how files are physically stored on the data nodes is abstracted. Every file has a unique address, with the HDFS scheme and a nested folder layout—e.g., hdfs://[namenode]/logs/2016/04/19/20/web-app-log-201604192049.gz.

Accessing HDFS from the command line

The hadoop command provides access to storage as well as to compute. The storage operations begin with fs (for “file system”), then typically follow with Linux file operation names. You can use hadoop fs –ls to list all the objects in HDFS. In order to read the contents of one or more files (which we have already seen), use hadoop fs -cat.

HDFS is a hierarchical file system that can store directories and files, and its security model is similar to Linux’s—objects have an owner and a group, and you can set read, write, and execute permissions on objects.

Note: Hadoop has wavered between having a single command for compute and storage or having separate ones. The hdfs command is also supported for storage access, but it provides the same operations as the hadoop command. Anywhere you see hdfs dfs in Hadoop literature, you can substitute it with hadoop fs for the same result.

Users in HDFS have their own home directory, and when you access objects, you can either specify a full path from the root of the file system or a partial path assumed to start from your home directory. In Code Listing 17, we create a directory called 'ch03' in the home directory for the root user and check that the folder is where we expect it to be.

Code Listing 17: Creating Directories in HDFS

# hadoop fs -mkdir -p /user/root/ch03 # hadoop fs -ls Found 1 items drwxr-xr-x - root supergroup 0 2016-04-15 16:44 ch03 # hadoop fs -ls /user/root Found 1 items drwxr-xr-x - root supergroup 0 2016-04-15 16:44 /user/root/ch03 |

In order to store files in HDFS, we can use the put operation, which copies files from the local file system, into HDFS. If we're using the hadoop-succinctly Docker container, the commands in Code Listing 18 copy some of the setup files from the container's file system into HDFS.

Code Listing 18: Putting Files into HDFS

# hadoop fs -put /hadoop-setup/ ch03 # hadoop fs -ls ch03/hadoop-setup Found 3 items -rw-r--r-- 1 root supergroup 294 2016-04-15 16:49 ch03/hadoop-setup/install-hadoop.sh -rw-r--r-- 1 root supergroup 350 2016-04-15 16:49 ch03/hadoop-setup/setup-hdfs.sh -rw-r--r-- 1 root supergroup 184 2016-04-15 16:49 ch03/hadoop-setup/setup-ssh.sh |

With the put command, we can copy individual files or whole directory hierarchies, which makes for a quick way of getting data into Hadoop.

Tip: When you're working on a single node, copying data into HDFS effectively means copying it from the local drive to a different location on the same local drive. If you're wondering why you have to do that, remember that Hadoop is inherently distributed. When you run hadoop fs -put on a single node, Hadoop simply copies the file—but run the same command against a multinode cluster and the source files will be split, distributed, and replicated among many data nodes. You use the exact same syntax for a development node running on Docker as for a production cluster with 100 nodes.

In order to fetch files from HDFS to the local file system, use the get operation. Many of the HDFS commands support pattern matching for source paths, which means you can use wildcards to match any part of filenames and the double asterisk to match files at any depth in the folder hierarchy.

Code Listing 19 shows how to locally copy any files whose name starts with 'setup' and that have the extension 'sh' in any folder under the 'ch03' folder.

Code Listing 19: Getting Files from HDFS

# mkdir ~/setup root@21243ee85227:/hadoop-setup# hadoop fs -get ch03/**/setup*.sh ~/setup root@21243ee85227:/hadoop-setup# ls ~/setup/ setup-hdfs.sh setup-ssh.sh |

There are many more operations available from the command line, and hadoop fs -help lists them all. Three of the most useful are tail (which reads the last 1KB of data in a file), stat (which sees useful stats on a file, including the degree of replication), and count (which tells how many files and folders are in the hierarchy).

Write once, read many

HDFS is intended as a write-once, read-many file system that significantly simplifies data access for the rest of the platform. As we've seen, in a MapReduce job, Hadoop streams through input files, passing each line to a mapper. If the file is editable, the contents can potentially change during the execution of the task. Content already processed might change or be removed entirely, invalidating the result of the job.

Storing data in Hadoop from the command line requires three operations: the put operation, which we've already seen; moveFromLocal, which deletes the local source files after copying them; and appendFromLocal, which adds the contents of local files to existing files in HDFS.

Append is an interesting operation, because we can't actually edit data in Hadoop. In earlier versions of Hadoop, append wasn't supported—we could only create new files and add data while the file handle was open. Once we closed the file, it became immutable and, instead of adding to it, we had to create a new file and write the contents of the original along with the new data we wanted to add, then save it with a different name.

HDFS’s ability to support append functionality has considerably broadened its potential—this means Apache's real-time Big Data platform, HBase, can use HDFS for reliable storage. And note that being append-only isn't the restriction it might seem if you're from a relational database background. Typically, Hadoop is used for batch processing over data that records something (an event or a fact), and that data is static.

You might have a file in Hadoop that records a day's worth of financial trades—those are a series of facts that will never change, so there's no need to edit the file. If a trade was booked incorrectly, it will be rebooked, which is a separate event that will be recorded in another day's file.

The second event may reverse the impact of the first event, but it doesn't mean the event never happened. In fact, storing both events permanently enables much richer analysis. If you allowed updates and could edit the original trade, you'd lose any record of the original state along with the knowledge that it had changed.

In order to append data without altering the original file, HDFS splits the new data into blocks and adds them to the original blocks into which the file was split.

File splits and replication

We saw in Chapter 1 that HDFS splits large files into blocks when we store them. The default block size can differ between Hadoop distributions (and we can configure it ourselves for the whole cluster and for individual files), but it's typically 128 MB. All HDFS read and write operations work at the block level, and an optimal block size can provide a useful performance boost.

The correct block size is a compromise, though—one that must balance some conflicting goals:

- The name node stores metadata entries for every file block in memory; smaller block size leads to significantly more blocks and higher metadata storage.

- Job tasks run at the block level, so having very large blocks means the system can get clogged with long-running tasks. Having smaller blocks can mean the cost of spinning up and managing tasks outweighs the benefit of having greater parallelism.

- Blocks are also the level of replication, so that having smaller blocks means having more blocks to distribute around the cluster. A greater degree of distribution can decrease the chances of scheduling a task to run on a node that keeps data locally.

Block size is one part of Hadoop configuration you can tune to your requirements. If you typically run jobs with very large inputs—running over terabytes of data—setting a higher block size can improve performance. A block size of 256 MB or even 512 MB is not unusual for larger workloads.

Another parameter we can change for our cluster, or for individual files, is the degree of replication. Figure 7 shows how some of the splits in a 1 GB file can be distributed across a cluster with 12 data nodes.

Figure 7: HDFS File Splits and Replication

With a default block size of 128 MB and a default replication factor of 3, HDFS will split the file into eight blocks, and each block will be copied to three servers: two on one rack and the third on a different rack. If you submit a job that queries the entire file, it will be split into eight tasks, each processing one block of the file.

In this example, there are more data nodes than there are tasks in the job. If the cluster is idle, Hadoop can schedule each task so it runs on a server that has the block locally. This, however, is a best-case scenario.

If the cluster isn't idle, or if you have files with a small number of blocks, or if there's a server outage, there's a much larger chance that a task must be scheduled on a node that doesn't keep the data locally. Reading data from another node in the same rack, or worse still, from a node in a different rack, might be orders of magnitude slower than reading from the local disk, which means tasks will take much longer to run.

HDFS lets you change the replication factor, but the optimal value is also a compromise between conflicting goals:

- A higher replication factor means blocks are copied to more data nodes, increasing the chances for tasks to be scheduled on a node that has the data locally.

- More replication means higher disk consumption for the same amount of raw data. A 10 GB file in HDFS will take up 30 GB of disk space with a replication factor of 3, but a 50 GB file will have a replication factor of 5.

Block size and replication factor are useful parameters to consider when it comes to tuning Hadoop for your own data landscape.

HDFS Client and the web UI

The Hadoop FS shell is the easiest way to get started with data access in HDFS, but for serious workloads you'll typically write data programmatically. HDFS supports a Java API and a REST API for programmatic access. And web UI, which you can use to explore the file system, is built into HDFS.

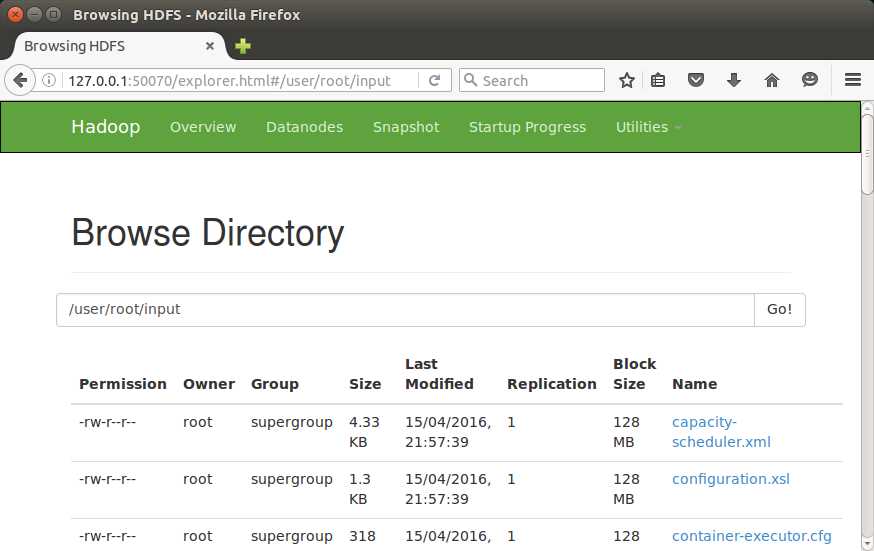

The web UI runs on the name node, on port 50070 (by default). That port is exposed by the hadoop-succinctly Docker container, which means you can browse to http://127.0.0.1:50070/explorer.html (substitute 127.0.0.1 with the IP address of your Docker VM if you're using Mac or Windows). Figure 8 shows how the storage browser looks.

From the browser, you can navigate around the directories in HDFS, see the block information for files, and download entire files. It's a useful tool for navigating HDFS, especially as it is read-only, so that the web UI can be given to users who don't otherwise have access to Hadoop.

Summary

In this chapter, we had a closer look at HDFS, the Hadoop Distributed File System. We learned how HDFS is architected with a single active name node that holds the metadata for all the files in the cluster and with multiple data nodes that actually store the data.

We got started reading and writing data from HDFS using the hadoop fs command line, and we learned how HDFS splits large files into blocks and replicates the blocks across many data nodes in order to provide resilience and enable high levels of parallelism for MapReduce tasks. We also learned that block size and replication factor are configurable parameters that you might need to flex in order to get maximum performance.

Lastly, we had a brief look at the HDFS explorer in the Hadoop Administration web UI. There are other UIs provided by embedded HTTP servers in Hadoop that we'll see in later chapters.

Next, we'll examine the other part of Hadoop—the resource negotiator and compute engine.

- 1800+ high-performance UI components.

- Includes popular controls such as Grid, Chart, Scheduler, and more.

- 24x5 unlimited support by developers.