CHAPTER 1

Go Gulp

Introduction

Gulp is an easy-to-learn, easy-to-use JavaScript task runner. It favors code over configuration and is fast while executing its tasks. It gained a lot of attention from front-end engineers worldwide and from Microsoft as it has become the default used in the ASP.NET templates in Visual Studio 2015.

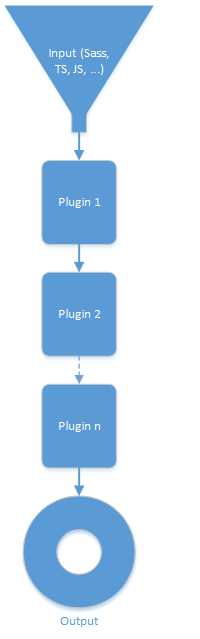

Gulp stream flow

Reading in files, processing them, and then writing the outcome is the bread and butter of a task runner. Unlike others, Gulp processes this stream of tasks in memory instead of writing the outcome of every step to disk. This makes it far more efficient and performant. The processing itself is done by plugins, small dedicated tasks that perform their dedicated logic on what they receive, and then pass it on. There’s already a bunch of them, and you can create new ones if you like. At the moment of writing, there are already 1,533 plugins available.

Let’s visualize this in an easy-to-understand flow diagram:

Figure 1: Gulp flow

Four APIs to rule them all

Gulp makes it easy for you to get started, as it only provides four API functions with which you can perform a lot of magic.

So, let’s take a look at these four API functions and what they have to offer.

gulp.src()

With the .src() function, you load a file or files with either a direct path or make use of the node-glob syntax. This latter is beyond the scope of this book but you can read all about it here.

gulp.dest()

After having gone through the stream of plugins and having their respective tasks performed, you likely want to have that hard work result in some output. With the dest() function, you can do just that, and write the output to disk.

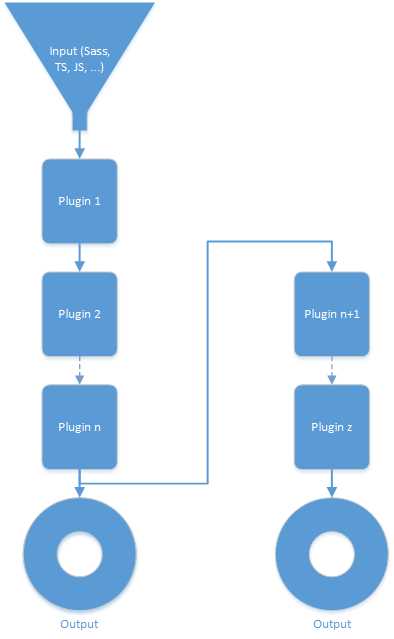

The dest() function emits all data passed to it. This means that it can write to multiple folders when needed. It is even possible to write the outcome of a flow and then continue working with that result and apply other plugins on it.

Code Listing 1

gulp.src('./client/templates/*.jade') .pipe(jade()) .pipe(gulp.dest('./build/templates')) .pipe(minify()) .pipe(gulp.dest('./build/minified_templates')); |

In the sample code, you can see that via the .src() function, files are being loaded and then piped into a flow existing of plugins and destinations. The files are being processed and written to ./build/templates, and then they are minified by another plugin, and the outcome of that is being written to ./build/minified_templates.

The visualization of this can be seen in the following figure:

Figure 2: Gulp flow with multiple destinations

gulp.task()

This forms a logical wrapper around the .src(), .dest(), and stream. When you make up your Gulp file, you can have more than one task defined, and even have dependencies defined before a certain task can run. A very simple task that takes files from one folder and copies them over to another could be the following:

Code Listing 2

gulp.task('copyScripts', function () { // copy any javascript files in source/ to public/ gulp.src('source/*.js').pipe(gulp.dest('public')); }); |

When run, the code functions as follows: the files in the source folder with extension .js will be copied over to the folder public. We will see how to run it in the next chapter.

gulp.watch()

This function keeps an eye on file changes and acts accordingly. Chapter 3 is going to be completely devoted to this.

npm and Node.js

As we saw before, Gulp makes use of plugins. These are distributed in an easy way through npm. You can search on that particular site for Gulp plugins. The good thing is, they usually start with gulp-. For example, if you open the npm webpage and type in the search box “gulp-clean-css,” you get to see how to install the plugin and API, and some samples on how to use it.

From these samples you can see that the syntax feels like Node.js syntax. That’s correct; Gulp builds on top of this framework. If you don’t know Node.js, that’s perfectly fine—you’ll still be able to follow along in this book.

- 1800+ high-performance UI components.

- Includes popular controls such as Grid, Chart, Scheduler, and more.

- 24x5 unlimited support by developers.