CHAPTER 2

Serving and Routing

Go’s net package facilitates all network communications in Go programs, whether it’s over HTTP, TCP/IP, WebSockets, or any other standard network protocol.

Of course, because this e-book addresses web development, we are primarily concerned with HTTP, which means the main subpackage we’ll be using is net/http.

In this chapter, we’ll look at the basic requirements of any Go web application—serving and routing—and how you can use net/http and complementary packages to implement them.

Go as a simple web server

Back in the old days, web servers did little more than serve up files that resided in a directory on that server. If that’s all we want now, we can do something very similar in Go by using the net/http package in just a few lines of code.

Code Listing 1: Go as a Web Server

package main import ( "net/http" ) func main() { http.ListenAndServe(":8999", } |

It’s very basic, but our program fulfills the core responsibilities of any web server—namely, listening to a request and serving a response. What’s more, because it doesn’t have to worry about all the other issues that a more traditional web server must, the program is lightning fast.

In this example, we call the http.ListenAndServe() function to send all requests on port 8999 to an http.FileServer handler method, which in turn accepts the directory on the server that we want to serve files from. Easy!

If you run the program using go run <program_name.go> and enter http://localhost:8999/ in your browser’s address bar, followed by the name of a file that exists in /var/www on your server, you’ll see that file’s contents displayed—as in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Go Serving Gophers

However, most modern web applications require a bit more than this from the server. And keep in mind, you’re not always going to be sending static content. Increasingly, you will be called upon to generate content dynamically, perhaps from the contents of a database. In this case, a physical file location doesn’t make much sense.

And suppose you have a more complex site structure in which your application’s files are spread among various subdirectories? For example, www.mysite.com/about/aboutus.html and www.mysite.com/blog/blog.html? This approach won’t work. So, you’ll need better control over the URLs your application can accept. You can achieve this by using the net/http package’s routing capabilities.

Simple serving and routing

Go relies on two main components to process HTTP requests—a multiplexor and handlers. A multiplexor (or “mux”) is essentially an HTTP request router. In Go’s net/http package, the multiplexor functionality is provided by ServeMux and the default serve mux is DefaultServeMux.

Intuitive, eh?

ServeMux compares incoming requests against a list of predefined URL paths, then calls the appropriate handler (a function that you define) for each path when there is a match.

Let’s first have a look at the code, then we’ll examine what’s going on.

Code Listing 2: Basic Serving and Routing Using Net/http

package main import ( "fmt" "html" "log" "net/http" "time" ) func main() { http.HandleFunc("/", showInfo) http.HandleFunc("/site", serveFile) err := http.ListenAndServe(":8999", nil) if err != nil { log.Fatal("ListenAndServe: ", err) } } func showInfo(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) { fmt.Fprintln(w, "Current time: ", time.Now()) fmt.Fprintln(w, "URL Path: ", html.EscapeString(r.URL.Path)) } func serveFile(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) { http.ServeFile(w, r, "index.html") } |

Notice that the main() function, which is the entry point into the program, sets up some server routes by using the http.HandleFunc(route, handler) method to map a URL route to a function that will respond to any requests coming in that match that route.

The program next calls the http.ListenAndServe() method, which starts an HTTP server with a specified address (in this case, the local machine on port 8999) and a mux. The mux in this instance is nil, which tells Go to use DefaultServeMux.

The handler functions do different things depending on whether the URL accessed is at the root of the site (“/”) or at “/site”. However, in both cases their method signatures must implement both http.ResponseWriter and http.Request. If a handler that does not implement both of these gets called via http.HandleFunc(), you’ll see that Go will raise a compile-time error.

If the user visits /site, the http.ServeFile() method handles the request and returns the index.html page that resides in the same directory as the application. You can use http.ServeFile() to send any static file in the response.

If the user visits the root location, showInfo() gets called and will display the current time and whichever path that user entered beyond the root URL. The application extracts this information by using the URL.Path property of the http.Request object that gets passed to the handler. The response is generated by http.ResponseWriter.

Start the program by issuing go run <program_name.go> from your IDE or simply via the command line. Next, visit localhost:8999 in your browser. Try various combinations to test its functionality.

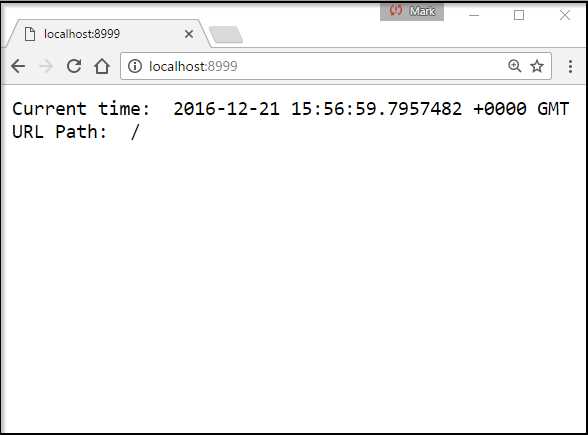

For example, entering http://localhost:8999 results in the dynamically generated page in Figure 5.

Figure 5: Visiting the Root of the Web Application

Entering any subroute (for example, localhost:8999/hello/there/from/golang) displays the time and date and the subroute entered, as we see in Figure 6.

Figure 6: Visting a Subroute

Entering localhost:8999/site displays the index.html page.

Figure 7: Visiting/Site

Let’s expand our ability to serve static files in this example. Suppose that the URL in the request starts with /static/ and we want to strip the /static part of the URL in order to look for the file referenced in the remaining path in the /var/www directory. We can use the StripPrefix function to achieve this, as we see in Code Listing 3.

Code Listing 3: Using StripPrefix

package main import ( "fmt" "html" "log" "net/http" "time" ) func main() { http.HandleFunc("/", showInfo) files := http.FileServer(http.Dir("/var/www")) http.Handle("/site/", http.StripPrefix("/site/", files)) err := http.ListenAndServe(":8999", nil) if err != nil { log.Fatal("ListenAndServe: ", err) } } func showInfo(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) { fmt.Fprintln(w, "Current time: ", time.Now()) fmt.Fprintln(w, "URL Path: ", html.EscapeString(r.URL.Path)) } |

Note that in this example we’re not calling HandleFunc, but Handle. That’s because the FileServer function returns its own handler that we can pass to the mux using Handle (instead of explicitly creating our own handler function).

So, you can see that it’s straightforward to get a site up and running that is self-serving (no separate web server required) and lets you respond to some simple requests.

Middleware

In web development, middleware is code that sits between the web request and your route handler. Middleware consists of reusable bits of code you can use to perform tasks that must occur either before the handler is called or afterward.

The term “middleware” is often used with Go programming, but you might also see similar terms used with other web languages and technologies, such as “interceptor,” “hooking,” and “request filtering.”

For example, you might want to check the status of a database connection or authenticate a user before routing the request. You might also want to compress the content of a response or limit the amount of times a specific handler is called—perhaps as part of some restriction that you place on users who access your web service free of charge.

Creating middleware is simply a matter of chaining handlers and handler functions, and it’s something you will see—and use—a lot in Go web development.

The basic idea is that you pass a handler function—let’s call it f2—into another handler function—let’s call this one f1—as a parameter. Handler f1 gets called when the route that triggers it is visited. f1 does some work, then calls f2.

Of course, you could have f1 call f2 directly. However, this is not ideal because we typically want to achieve a clear separation of concerns, and therefore our handler code should really be limited to processing the request and not doing whatever f2 is designed to do.

Here’s the basic idea—instead of dealing with the response as part of your handler, you simply pass the next handler in the chain to it.

Functions that accept another handler function as a parameter and return a new one can perform tasks before or after the handler is called (or both before and after) and can even ultimately choose not to call the original handler at all (if that is your intention).

Consider the example in Code Listing 4.

Code Listing 4: Middleware Example 1

package main import ( "fmt" "net/http" ) func middleware1(next http.Handler) http.Handler { return http.HandlerFunc(func(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) { fmt.Fprintln(w, "Executing middleware1()...") next.ServeHTTP(w, r) fmt.Fprintln(w, "Executing middleware1() again...") }) } func middleware2(next http.Handler) http.Handler { return http.HandlerFunc(func(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) { fmt.Fprintln(w, "Executing middleware2()...") if r.URL.Path != "/" { return } next.ServeHTTP(w, r) fmt.Fprintln(w, "Executing middleware2() again...") }) } func final(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) { fmt.Fprintln(w, "Executing final()...") fmt.Fprintln(w, "Done") } func main() { finalHandler := http.HandlerFunc(final) http.Handle("/", middleware1(middleware2(finalHandler))) http.ListenAndServe(":8999", nil) } |

Look at the main() function. Here, we are intercepting requests to our root web directory with the middleware1 handler. This handler accepts as a parameter another handler called middleware2. That in turn has the final handler as a parameter.

When someone visits our web application, it will call middleware1, which displays a message and, when it hits next.serveHTTP, executes the code in middleware2. The middleware2 function in turn calls final, which executes and then returns control to middleware2, which completes its tasks and returns control to middleware1.

The output will look like Figure 8.

Figure 8: The Output of Middleware Example 1

Figure 8 offers a completely artificial example, but it serves to illustrate how much control middleware can give you.

Go often uses middleware internally. For example, many functions in the net/http package, such as StripPrefix, are textbook examples of what middleware is—they wrap your handler and perform additional operations on requests or responses.

The concept of middleware can be somewhat difficult to understand, so Code Listing 5 shows another example.

Code Listing 5: Middleware Example 2

package main import ( "net/http" ) type AfterMiddleware struct { handler http.Handler } func (a *AfterMiddleware) ServeHTTP(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) { a.handler.ServeHTTP(w, r) w.Write([]byte(" +++ Hello from middleware! +++ ")) } func myHandler(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) { w.Write([]byte(" *** Hello from myHandler! *** ")) } func main() { mid := &AfterMiddleware{http.HandlerFunc(myHandler)} println("Listening on port 8999") http.ListenAndServe(":8999", mid) } |

In this bit of code, we want our middleware to execute when the myHandler function writes the response body—and to append some data to it.

First, we create a type for the middleware that we call AfterMiddleware. This consists of a single field—the http.Handler we want our middleware to respond to.

The http.Handler interface requires only that we implement the ServeHTTP interface:

type Handler interface {

ServeHTTP(ResponseWriter, *Request)

}

We do this as follows:

func (a *AfterMiddleware) ServeHTTP(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

a.handler.ServeHTTP(w, r)

w.Write([]byte(" +++ Hello from middleware! +++ "))

}

Now, the response consists of whatever myHandler wrote and is followed by the output of our middleware in Figure 9.

![]()

Figure 9: The Output of Middleware Example 2

We cannot cover every aspect of middleware here, but it is a very powerful feature that is well worth investigating. This article and video lecture by Mat Ryer is an excellent introduction to the topic.

We’ll revisit the concept of middleware in Chapter 7, when we create some eminently more useful logging middleware.

More advanced serving and routing with the Gorilla Web Toolkit

The routing functionality offered by Go’s built-in net/http package only gets you so far. If the range of possible URLs is complex and if, for example, you want to be able to use regular expressions or variables to match URLs, you will probably want to consider a third-party solution.

The Gorilla Web Toolkit is one such solution. Gorilla consists of 22 packages, including:

- gorilla/context stores global request variables.

- gorilla/mux is a powerful URL router and dispatcher.

- gorilla/reverse produces reversible regular expressions for regexp-based muxes.

- gorilla/rpc implements RPC over HTTP with codec for JSON-RPC.

- gorilla/schema converts form values to a struct.

- gorilla/securecookie encodes and decodes authenticated and optionally encrypted cookie values.

- gorilla/sessions saves cookie and filesystem sessions and allows custom session back ends.

- gorilla/websocket implements the WebSocket protocol defined in RFC 6455.

As you can see from the list of packages, there is more to Gorilla than merely an alternative mux for Go routing and serving. In fact, it provides a whole range of different tools to assist you in your web development efforts.

But here, we’re interested in the mux. The gorilla/mux module implements the http.Handler interface so that it is compatible with the standard Golang. http.serveMux.

In addition, the gorilla/mux module gives you the ability to:

- Match requests based on URL host, path, path prefix, schemes, header and query values, HTTP methods, or custom matchers that you define.

- Register URLs so that you can build or “reverse” them, thereby maintaining references to resources.

- Use “subrouters”—nested routes that are only tested if their parent routes match. In this way, you can define “groups” of routes that all have something in common, such as a host or a path prefix. This optimizes request matching by undertaking some tests only if they are appropriate to the group (rather than executing tests against all incoming requests).

Installing and referencing the gorilla/mux package

If you are only interested in the more advanced routing capability offered by Gorilla, you can install gorilla/mux in your GOPATH by using go get. For example, assuming that you have git installed:

go get github.com/gorilla/mux

Next, you must import it into your application, like so:

package main

import (

github.com/gorilla/mux

...

)

Using gorilla/mux

For a bit of fun, let’s use gorilla/mux to create a handler that matches incoming requests for product IDs based on a regular expression. If the product ID is a single digit long, we have a match and can route to the appropriate page. If not, we route to an error page.

We’ll first need to import the gorilla/mux module, which we do in the normal way:

import(

. . .

github.com/gorilla/mux

)

Next, we’ll need to tell Go to use gorilla/mux instead of its own DefaultServeMux:

func main() {

router = mux.NewRouter()

}

When we’ve done that, we can use the handler functions we are familiar with, but in the context of router and with the extra capabilities gorilla/mux provides, such as searching for a URL parameter with a regular expression:

router.HandleFunc("/product/{id:[0-9]+}", pageHandler)

That line of code creates a handler function that attempts to match a URL that consists of /product/ with a number from zero to nine, inclusive, which it refers to as id. If there is a match, it calls the pageHandler function.

In our pageHandler function, we need a way to examine the exact string that HandleFunc matched. We can use Gorilla’s mux.Vars function to do this, passing in the request as a single parameter and getting back a map of route variables. We can reference the route variable we’re interested in by its name—id.

Having retrieved the product ID, we can next check for a matching HTML page. Go’s os module provides the Stat and IsNotExist functions to help us with that. If the file exists on the server, we use http.ServeFile in order to send it to the browser. And if it doesn’t exist there, we’ll return another page telling the user that the product is invalid.

Code Listing 6 shows the full code.

Code Listing 6: Serving and Routing Using gorilla/mux

package main import ( "log" "net/http" "os" "github.com/gorilla/mux" ) func pageHandler(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) { vars := mux.Vars(r) productID := vars["id"] log.Printf("Product ID:%v\n", productID) fileName := productID + ".html" if _, err := os.Stat(fileName); os.IsNotExist(err) { log.Printf("no such product") fileName = "invalid.html" } http.ServeFile(w, r, fileName) } func main() { router := mux.NewRouter() router.HandleFunc("/product/{id:[0-9]+}", pageHandler) http.Handle("/", router) http.ListenAndServe(":8999", nil) } |

This only scratches the surface of what gorilla/mux can do. For example, you can match against:

Path prefixes:

router.PathPrefix("/products/")

HTTP methods:

router.Methods("GET", "POST")

URL schemes:

router.Schemes("https")

Header values (for example, was the request an AJAX request?):

router.Headers("X-Requested-With", "XMLHttpRequest")

Query values:

router.Queries("key", "value")

Custom matching functions that you define:

router.MatcherFunc(func(r *http.Request, match *RouteMatch) bool {

// do something

})

You can also combine multiple matchers in a single route by chaining function calls:

router.HandleFunc("/products", productHandler).

Host("www.example.com").

Methods("GET").

Schemes("https")

Or, you can use subroutes to group multiple routes together. For example, the following code looks for a host name of www.example.com, but it will check the subroutes only if it gets a match on the host name:

router := mux.NewRouter()

subrouter := route.Host("www.example.com").Subrouter()

// Register the subroutes

subrouter.HandleFunc("/products/", AllProductsHandler)

subrouter.HandleFunc("/products/{name}", ProductHandler)

subrouter.HandleFunc("/reviews/{category}/{id:[0-9]+}"), ReviewsHandler)

The gorilla/mux package is a very capable alternative to DefaultServeMux and well worth investigating. You can find out more at http://www.gorillatoolkit.org/pkg/mux.

Of course, with Go being such a vibrant ecosystem, there are many other choices if you don’t like Gorilla. I prefer Gorilla because it’s easy to get my head around, and it’s always been able to do whatever I ask it to do.

Other popular third-party routers include:

- httprouter: Lightning fast, but less capable than Gorilla. For example, you cannot include regular expressions in your routes.

- Httptreemux: A fast, flexible, tree-based HTTP router, inspired by httprouter.

- Pat: Simple to use and quite popular. If you’re a Ruby-ist familiar with Sinatra and Rails, you’ll find Pat’s approach very familiar.

Returning errors

Things don’t always work as we intend. Requests get made for pages that no longer exist, things get moved from one place to another, and sometimes the connection drops.

The HTTP protocol defines 61 different status codes so that we can determine whether or not a request was successful.

Here are a few of the most common ones:

- 200 OK: Hooray! All is well.

- 404 Not found: Whatever resource you’re looking for, you won’t find it here.

- 301 Moved Permanently: Used as a permanent redirect to another page.

- 301 Moved Temporarily: Used as a temporary redirect to another page.

- 500 Internal Server Error: Something unexpected has gone wrong. This is a “catch all.”

The net/http package provides a function called Error that you can use to handle error status codes. Your job as a developer is to pick one that makes sense for the type of error you are reporting.

You can raise an error by passing the ResponseWriter, a string message, and the status code. For example, this raises a 404 Not Found error:

http.HandleFunc("/", func(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

http.Error(w, "Something has gone wrong", 500)

})

However, it’s better practice to use the various helper functions that net/http provides for this purpose rather than the generic http.Error() function.

For example:

// Return 404 Not Found

http.NotFound(w, req)

// Return 301 Permanently Moved

http.Redirect(w, req, “http://somewhereelse.com”, 301)

// Return 302 Temporarily Moved

http.Redirect(w, req “http://temporarylocation”, 302)

- 1800+ high-performance UI components.

- Includes popular controls such as Grid, Chart, Scheduler, and more.

- 24x5 unlimited support by developers.