CHAPTER 5

Creating a RESTful JSON API

We’ve learned a lot already, so let’s see if we can take all that knowledge and do something useful with it.

In Chapter 1, we examined how Go is an excellent choice for creating web services for many reasons—for example, its ability to scale massively through its lightweight threading model, its ease with modularizing code, and its ability to integrate with common tools such as cryptographic libraries, secure web protocols, and, of course, HTTP servers.

In this chapter, I want to demonstrate how we can create a simple RESTful web service that can accept JSON requests and return JSON responses in order to facilitate CRUD (Create, Read, Update, and Delete) operations on a database.

(Actually, I’m going a cheat a little here. In order to minimize the complexity of our application, I’m going to create a CRD application. The Update functionality will be left as an exercise for the reader!)

This application will use what we’ve learned so far about serving, routing, and accessing a database. In building it, I’ll show you how you might design and develop a typical web service. It won’t be perfect or production-ready, but it should give you a good idea of how easy it is to build these sorts of services in Go.

RESTful APIs

If you’ve been a developer, or if you’ve spent any time with developers, you have no doubt heard about REST. Given the amount of hype it has attracted in recent years, you would think that it, too, was a recent concept. But it’s not. In fact, it’s as old as the web itself.

REST is simply a response to the hundreds of different protocols that have been developed over the years that have aimed to get computers talking to each other over networks using the same language.

Some of these protocols have included SOAP (which, because of its reliance on XML as a transport mechanism, requires a fair amount of data and computing power and began to fall out of favor as mobile devices became ubiquitous), JMS (which is specific to Java applications and therefore not really geared for widespread adoption), and XML-RPC (which, like SOAP, uses XML but without implementing any of the standards that SOAP has).

As with all these approaches, the aim behind REST was to make sharing data easy for computers while at the same time being transparent enough that human observers can understand what they are doing.

What REST offers, however, is the ability to do this while remaining very lightweight. Its methods are familiar to developers because it uses the same, established methods employed by the web itself.

How so?

Well, consider a website that you access in a browser. You enter a URL to visit the site, and the program behind the site can analyze that URL in order to understand your intention. In a static site, you’re simply entering URLs that point to file resources on the web server, but in a site that employs web services, you can effectively use the URL as a command line and enter requests not only for resources, but also for specific operations that the program’s API exposes.

Consider the Open Movie Database website (http://www.omdbapi.com) that provides a free REST API to access information about movies. You need only to craft the URL so that it specifies what information you want it to give you.

If you start at https://www.omdbapi.com/, you get the home page in Figure 19.

Figure 18: The Open Movie Database API Home Page

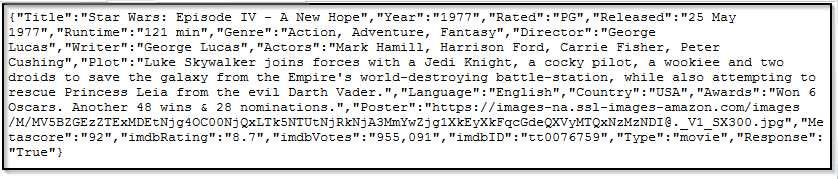

If you specify a movie using the t (title) parameter, you get something a little more interesting: https://www.omdbapi.com/?t=star%20wars.

Figure 19: Accessing the Open Movie Database API

That information is JSON, or JavaScript Object Notation. Despite the name, it’s not specific to JavaScript. In fact, it’s a common way of encoding data in a very lightweight format, and it’s used by applications written in many different languages, including Go.

Apart from being lightweight and easily parsed by client applications, JSON is also human readable. Well, just barely. You can tidy up the response either by viewing it in your browser’s developer console or by installing an extension that prettifies a JSON response.

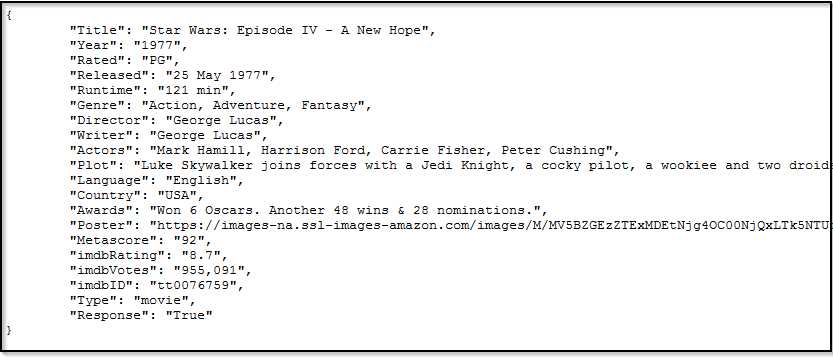

Figure 21 shows the output after I’ve installed the JSON Formatter add-on in Firefox.

Figure 20: The JSON Response, Prettified

As you can see, JSON is simply a bunch of key/value pairs. Everything inside the curly braces is a JSON object, and objects themselves can contain other objects and arrays of values.

However, this isn’t a JSON tutorial. You can find out about JSON almost anywhere on the web, and there isn’t a lot to it. The takeaway here is that APIs exist that can parse a URL and return data in the JSON format that can be consumed by a client application. Some sites can even accept JSON, too, but the Open Movie Database isn’t one of them.

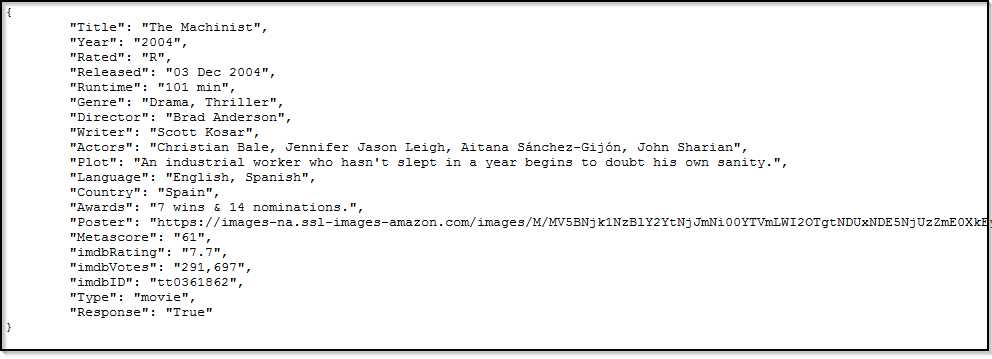

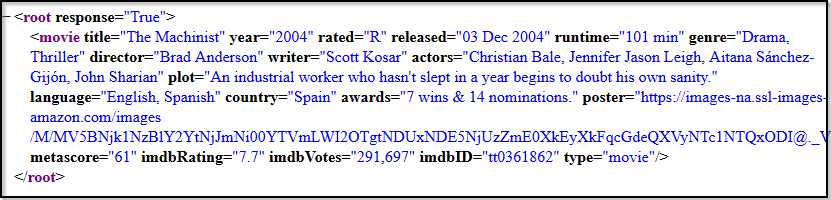

We can also add other criteria. Figure 22 looks for a film called The Machinist, includes a short plot summary, and returns the results as JSON (the default): http://www.omdbapi.com/?t=the+machinist&y=&plot=short&r=json.

Figure 21: Open Movie Database API Results for The Machinist

Figure 23 sets the r (response) parameter to XML: http://www.omdbapi.com/?t=the+machinist&y=&plot=short&r=xml.

Figure 22: Changing the Output to XML Format

That’s pretty concise as far as XML goes. A lot of XML is deeply nested and is a nightmare to parse, hence the preference for JSON in modern APIs.

Play around with the Open Movie Database API for a bit. I’ll wait!

So, that’s an example of a RESTful API. You’re effectively using the URL itself to make calls to the web service.

Our RESTful web service

We’re going to build something similar in this chapter.

You’ve probably already thought: “I could do that with Go routers!” And, indeed, you can. So, all you need to get going is some data. And we’ve already been playing around with MySQL’s “world” database, so let’s use that.

Our application will allow users to enter any of the following URL paths and respond in the way described:

- http://localhost:8999/city: Return a list of all cities in the City table in JSON format.

- http://localhost:8999/city/1028: Return details of the city with ID 1028 in JSON format.

- http://localhost:8999/cityadd/: Allow the user to POST a JSON representation of a new city and get a JSON result object back.

- http://localhost:8999/citydel/1028: Allow the user to delete the city with ID 1028 and get a JSON result object back.

In order to make this work while keeping our code as modular as possible, we’re going to create the following files:

- main.go

- handlers.go

- router.go

- routes.go

- database.go

- city.go

- dbupdate.go

Those module names should be self-explanatory. Let’s dive into it.

Serving and routing

Let’s define our routes first. We’re going to use gorilla/mux instead of net/http’s DefaultServeMux because gorilla/mux is generally nicer to work with. And instead of simply defining them one at a time, we’re going to store route details in a struct in order to make it easier to add new routes when we need them.

Here is routes.go, which defines each of the routes and their handlers in a slice (roughly analogous to arrays in other programming languages) of Route types, called Routes.

Code Listing 17: routes.go

package main import "net/http" type Route struct { Name string Method string Pattern string HandlerFunc http.HandlerFunc } type Routes []Route var routes = Routes{ Route{ "HomePage", "GET", "/", HomePage, }, Route{ "CityList", "GET", "/city", CityList, }, Route{ "CityDisplay", "GET", "/city/{id}", CityDisplay, }, Route{ "CityAdd", "POST", "/cityadd", CityAdd, }, Route{ "CityDelete", "GET", "/citydel/{id}", CityDelete, }, } |

And here in Code Listing 18 is router.go, which loops through the Routes and creates handlers for them.

Code Listing 18: router.go

package main import "github.com/gorilla/mux" func NewRouter() *mux.Router { router := mux.NewRouter().StrictSlash(true) for _, route := range routes { router. Methods(route.Method). Path(route.Pattern). Name(route.Name). Handler(route.HandlerFunc) } return router } |

In order to get all those routes up and running and ready to serve requests, we simply need to create an instance of NewRouter in our main function, but we’ll get around to that in a bit.

Let’s begin by having a look at each of the handlers in handlers.go.

First is the CityList handler, which gets called when a user visits http://localhost:8999/city.

Code Listing 19: The CityList Handler

func CityList(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) { // Query the database jsonCities := dbCityList() ... } |

CityList calls dbCityList in our database.go module in order to query the database and return a list of cities in JSON format. In order to work with JSON in Go applications, you need the encoding/json package. Then you can call json.Marshal to turn a struct into JSON and json.Unmarshal to turn JSON into a struct.

Code Listing 20: Encoding the Query Response as JSON

// Find all cities and return as JSON. func dbCityList() []byte { var cities Cities var city City cityResults, err := database.Query("SELECT * FROM city") if err != nil { log.Fatal(err) } defer cityResults.Close() for cityResults.Next() { cityResults.Scan(&city.Id, &city.Name, &city.CountryCode, &city.District, &city.Population) cities = append(cities, city) } jsonCities, err := json.Marshal(cities) if err != nil { fmt.Printf("Error: %s", err) } return jsonCities } |

As in Chapter 3, we’re using the Query method to pass SQL to our database server, then calling Next on the result set to iterate through each row that the query returns, and we’re also calling Scan to map the columns in each row to fields in our City struct.

Back in our handler, CityList, we’re writing out the appropriate JSON headers in the response, then returning the JSON we received from dbCityList, as in Code Listing 21.

Code Listing 21: Returning the JSON Response Containing a List of Cities

func CityList(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) { // Query the database. jsonCities := dbCityList() // Format the response. w.Header().Set("Content-Type", "application/json") w.WriteHeader(http.StatusOK) w.Write(jsonCities) } |

Let’s look at another handler—CityDisplay. This handler accepts an id parameter for a specific city that we then pass to the dbCityDisplay function in database.go. If all goes well, we receive a JSON object that describes only that city and returns it in our response, as in Code Listing 22.

Code Listing 22: Sending a JSON Response for a Single City

func CityDisplay(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) { // Get URL parameter with the city ID to search for. vars := mux.Vars(r) cityId, _ := strconv.Atoi(vars["id"]) // Query the database. jsonCity := dbCityDisplay(cityId) // Send the response. w.Header().Set("Content-Type", "application/json") w.WriteHeader(http.StatusOK) w.Write(jsonCity) } |

Code Listing 23 shows the dbCityDisplay function that provides the JSON data for a specific city.

Code Listing 23: Finding a Single City by Using QueryRow

// Find a single city based on ID and return as JSON. func dbCityDisplay(id int) []byte { var city City err := database.QueryRow("SELECT * FROM city WHERE ID=?", id).Scan(&city.Id, &city.Name, &city.CountryCode, &city.District, &city.Population) if err != nil { log.Fatal(err) } jsonCity, err := json.Marshal(city) if err != nil { fmt.Printf("Error: %s", err) } return jsonCity } |

Note that dbCityDisplay expects to return only a single row from the database, so we’re using QueryRow instead of Query. We don’t need to defer the closing of the record set because that’s done explicitly when the query returns with either a single record or with no record. We need to chain the call to Scan to the call to QueryRow because otherwise the recordset will be closed before we have a chance to work with it.

CityAdd is a little more complex because we must read the JSON from the body of the request, unmarshall it into a Go struct, then pass it to dbCityAdd to process it.

Code Listing 24: The CityAdd Function

func CityAdd(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) { var city City // Read the body of the request. body, err := ioutil.ReadAll(io.LimitReader(r.Body, 1048576)) if err != nil { panic(err) } if err := r.Body.Close(); err != nil { panic(err) } // Convert the JSON in the request to a Go type. if err := json.Unmarshal(body, &city); err != nil { w.Header().Set("Content-Type", "application/json") w.WriteHeader(422) // can't process! if err := json.NewEncoder(w).Encode(err); err != nil { panic(err) } } // Write to the database. addResult := dbCityAdd(city) // Format the response. w.Header().Set("Content-Type", "application/json") w.WriteHeader(http.StatusCreated) w.Write(addResult) } |

Notice how we’re setting a 1MB limit on the amount of data we’ll accept from the client. The last thing we want is some malicious user sending us a terabyte of data and crashing our server!

Tip: Always limit the amount of data you will allow a client to send to your application.

When we have the JSON in a Go struct, we can prepare a statement in SQL, then execute it with the new city record we want to add. The benefit of preparing a statement in this way, by using db.Prepare, is that it helps protect against SQL injection if the same malicious user tries to sabotage us using another favorite hacker’s technique.

Code Listing 25: Using a Prepared Statement for the INSERT Operation

// Create a new city based on the information supplied. func dbCityAdd(city City) []byte { var addResult DBUpdate // Create prepared statement. stmt, err := database.Prepare("INSERT INTO City(Name, CountryCode, District, Population) VALUES(?,?,?,?)") if err != nil { log.Fatal(err) } // Execute the prepared statement and retrieve the results. res, err := stmt.Exec(city.Name, city.CountryCode, city.District, city.Population) if err != nil { log.Fatal(err) } lastId, err := res.LastInsertId() if err != nil { log.Fatal(err) } rowCnt, err := res.RowsAffected() if err != nil { log.Fatal(err) } // Populate DBUpdate struct with last Id and num rows affected. addResult.Id = lastId addResult.Affected = rowCnt // Convert to JSON and return. newCity, err := json.Marshal(addResult) if err != nil { fmt.Printf("Error: %s", err) } return newCity } |

Note also that the INSERT operation on the database retrieves some useful information—namely the ID of the recently added record and the number of records affected. We’re storing this in a struct called DBUpdate so that we can return it to the CityAdd handler and, subsequently, to the client (who may wish to act on the information).

The last of our handlers is CityDelete. Like CityDisplay, it requires users to enter the ID of the city with which they want to work.

Code Listing 26: The CityDelete Function

func CityDelete(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) { // Get URL parameter with the city ID to delete. vars := mux.Vars(r) cityId, _ := strconv.ParseInt(vars["id"], 10, 64) // Query the database. deleteResult := dbCityDelete(cityId) // Send the response. w.Header().Set("Content-Type", "application/json") w.WriteHeader(http.StatusOK) w.Write(deleteResult) } |

The corresponding dbCityDelete function takes that ID and prepares a DELETE statement with it. The database responds with the number of rows affected, and we can use the same DBUpdate struct to present that information to the user.

Code Listing 27: The dbCityDelete Function

// Delete the city with the supplied ID. func dbCityDelete(id int64) []byte { var deleteResult DBUpdate // Create prepared statement. stmt, err := database.Prepare("DELETE FROM City WHERE ID=?") if err != nil { log.Fatal(err) } // Execute the prepared statement and retrieve the results. res, err := stmt.Exec(id) if err != nil { log.Fatal(err) } rowCnt, err := res.RowsAffected() if err != nil { log.Fatal(err) } // Populate DBUpdate struct with last Id and num rows affected. deleteResult.Id = id deleteResult.Affected = rowCnt // Convert to JSON and return. deletedCity, err := json.Marshal(deleteResult) if err != nil { fmt.Printf("Error: %s", err) } return deletedCity } |

And that’s really it!

The complete application

Let’s next examine a number of code listing examples that demonstrate the complete application as we separate the various concerns into these modules:

- main.go

- router.go

- routes.go

- handlers.go

- database.go

- city.go

- dbupdate.go

Code Listing 28: main.go

package main import ( "log" "net/http" ) func main() { router := NewRouter() dbConnect() log.Fatal(http.ListenAndServe(":8999", router)) } |

Code Listing 29: router.go

package main import "github.com/gorilla/mux" func NewRouter() *mux.Router { router := mux.NewRouter().StrictSlash(true) for _, route := range routes { router. Methods(route.Method). Path(route.Pattern). Name(route.Name). Handler(route.HandlerFunc) } return router } |

Code Listing 30: routes.go

package main import "net/http" type Route struct { Name string Method string Pattern string HandlerFunc http.HandlerFunc } type Routes []Route var routes = Routes{ Route{ "HomePage", "GET", "/", HomePage, }, Route{ "CityList", "GET", "/city", CityList, }, Route{ "CityDisplay", "GET", "/city/{id}", CityDisplay, }, Route{ "CityAdd", "POST", "/cityadd", CityAdd, }, Route{ "CityDelete", "GET", "/citydel/{id}", CityDelete, }, } |

Code Listing 31: handlers.go

package main import ( "encoding/json" "fmt" "io" "io/ioutil" "net/http" "strconv" "github.com/gorilla/mux" ) func HomePage(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) { fmt.Fprintln(w, "Welcome to the City Database!") } func CityList(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) { // Query the database. jsonCities := dbCityList() // Format the response. w.Header().Set("Content-Type", "application/json") w.WriteHeader(http.StatusOK) w.Write(jsonCities) } func CityDisplay(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) { // Get URL parameter with the city ID to search for. vars := mux.Vars(r) cityId, _ := strconv.Atoi(vars["id"]) // Query the database. jsonCity := dbCityDisplay(cityId) // Format the response. w.Header().Set("Content-Type", "application/json") w.WriteHeader(http.StatusOK) w.Write(jsonCity) } func CityAdd(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) { var city City // Read the body of the request. body, err := ioutil.ReadAll(io.LimitReader(r.Body, 1048576)) if err != nil { panic(err) } if err := r.Body.Close(); err != nil { panic(err) } // Convert the JSON in the request to a Go type. if err := json.Unmarshal(body, &city); err != nil { w.Header().Set("Content-Type", "application/json") w.WriteHeader(422) // can't process! if err := json.NewEncoder(w).Encode(err); err != nil { panic(err) } } // Write to the database. addResult := dbCityAdd(city) // Format the response. w.Header().Set("Content-Type", "application/json") w.WriteHeader(http.StatusCreated) w.Write(addResult) } func CityDelete(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) { // Get URL parameter with the city ID to delete. vars := mux.Vars(r) cityId, _ := strconv.ParseInt(vars["id"], 10, 64) // Query the database. deleteResult := dbCityDelete(cityId) // Format the response. w.Header().Set("Content-Type", "application/json") w.WriteHeader(http.StatusOK) w.Write(deleteResult) } |

Code Listing 32: database.go

package main import ( "database/sql" "encoding/json" "fmt" "log" _ "github.com/go-sql-driver/mysql" ) var database *sql.DB // Connect to the "world" database. func dbConnect() { db, err := sql.Open("mysql", "root:password@tcp(127.0.0.1:3306)/world") if err != nil { log.Println("Could not connect!") } database = db log.Println("Connected.") } // Find all cities and return as JSON. func dbCityList() []byte { var cities Cities var city City cityResults, err := database.Query("SELECT * FROM city") if err != nil { log.Fatal(err) } defer cityResults.Close() for cityResults.Next() { cityResults.Scan(&city.Id, &city.Name, &city.CountryCode, &city.District, &city.Population) cities = append(cities, city) } jsonCities, err := json.Marshal(cities) if err != nil { fmt.Printf("Error: %s", err) } return jsonCities } // Find a single city based on ID and return as JSON. func dbCityDisplay(id int) []byte { var city City err := database.QueryRow("SELECT * FROM city WHERE ID=?", id).Scan(&city.Id, &city.Name, &city.CountryCode, &city.District, &city.Population) if err != nil { log.Fatal(err) } jsonCity, err := json.Marshal(city) if err != nil { fmt.Printf("Error: %s", err) } return jsonCity } // Create a new city based on the information supplied. func dbCityAdd(city City) []byte { var addResult DBUpdate // Create prepared statement. stmt, err := database.Prepare("INSERT INTO City(Name, CountryCode, District, Population) VALUES(?,?,?,?)") if err != nil { log.Fatal(err) } // Execute the prepared statement and retrieve the results. res, err := stmt.Exec(city.Name, city.CountryCode, city.District, city.Population) if err != nil { log.Fatal(err) } lastId, err := res.LastInsertId() if err != nil { log.Fatal(err) } rowCnt, err := res.RowsAffected() if err != nil { log.Fatal(err) } // Populate DBUpdate struct with last Id and num rows affected. addResult.Id = lastId addResult.Affected = rowCnt // Convert to JSON and return. newCity, err := json.Marshal(addResult) if err != nil { fmt.Printf("Error: %s", err) } return newCity } // Delete the city with the supplied ID. func dbCityDelete(id int64) []byte { var deleteResult DBUpdate // Create prepared statement. stmt, err := database.Prepare("DELETE FROM City WHERE ID=?") if err != nil { log.Fatal(err) } // Execute the prepared statement and retrieve the results. res, err := stmt.Exec(id) if err != nil { log.Fatal(err) } rowCnt, err := res.RowsAffected() if err != nil { log.Fatal(err) } // Populate DBUpdate struct with last Id and num rows affected. deleteResult.Id = id deleteResult.Affected = rowCnt // Convert to JSON and return. deletedCity, err := json.Marshal(deleteResult) if err != nil { fmt.Printf("Error: %s", err) } return deletedCity } |

Code Listing 33: city.go

package main type City struct { Id int `json:"id"` Name string `json:"name"` CountryCode string `json:"country"` District string `json:"district"` Population int `json:"pop"` } type Cities []City |

Code Listing 34: The dbUpdate Struct in dbupdate.go

package main type DBUpdate struct { Id int64 `json:"id"` Affected int64 `json:"affected"` } |

Running the application

We can test the application from within a browser, but that will involve a bit of fiddling around with the developer console and more clicks than necessary.

Instead, let’s use a command-line utility called curl (“client URL”).

If you have a Mac or Linux machine, curl is probably already available to you. If you have Windows, perhaps the easiest way to access it is by downloading the Git Bash shell that contains curl and a wealth of other useful Linux tools. There's even a native Bash shell for Windows—see https://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/commandline/wsl/about. It’s handy to have around even if you don’t use Git. Another alternative (although, in my opinion, a more bloated alternative) is Cygwin.

You can download Git Bash at https://git-for-windows.github.io/.

Displaying all cities

Open two shell windows.

Run the application in the first shell by executing go run *.go in the same folder as your application modules, as in Figure 24.

Figure 23: Running the Application

Next, enter the following command in the second shell window:

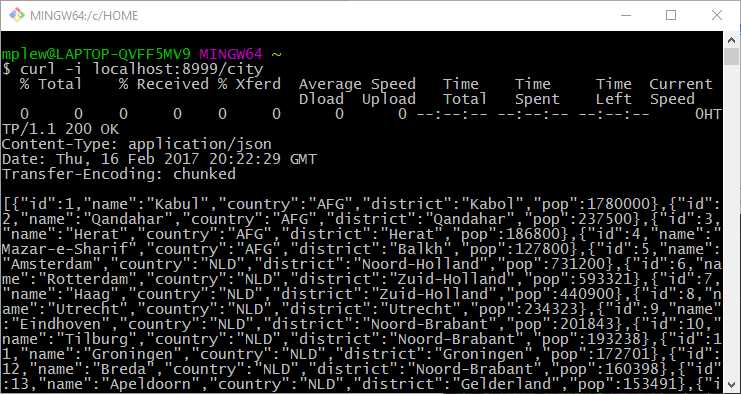

curl -i localhost:8999/city

The -i flag instructs curl to include the HTTP header.

You should see a JSON representation of every city in the City table, as shown in Figure 25.

Figure 24: Requesting All Cities

Displaying a specific city

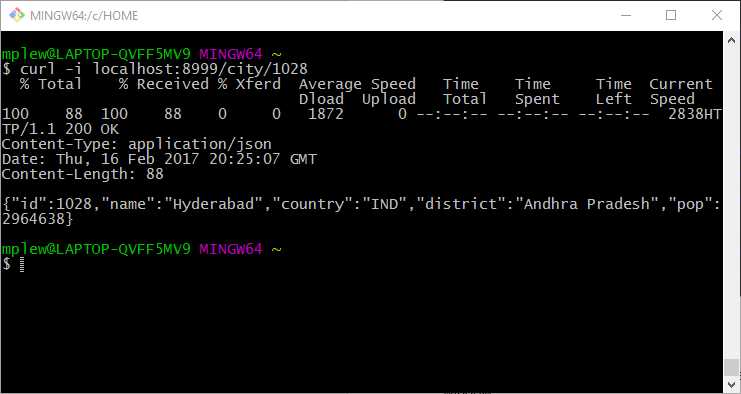

With the application still running in the first shell window, enter the following in the second shell window:

curl -i localhost:8999/city/1028

You should see details for the city with the ID of 1028—namely, Hyderabad in India. Enter some random city IDs and see which cities are referenced.

Figure 25: Requesting a Specific City by ID

Adding a city

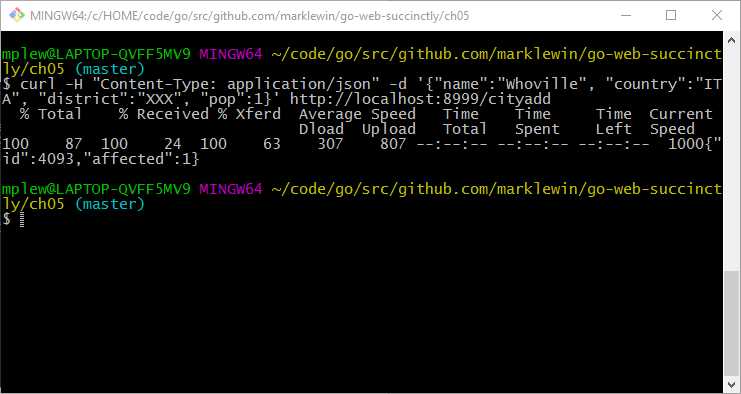

In the second shell window, enter the following:

curl -H "Content-Type: application/json" -d '{"name":"Whoville", "country":"ITA", "district":"XXX", "pop":1}' http://localhost:8999/cityadd

Tip: Take care when entering the JSON object that represents the new city. JSON is simple, but it is not forgiving if you forget to close quotes or braces, or if you put quotes (that denote the string data type) around a value that is expected to be an integer.

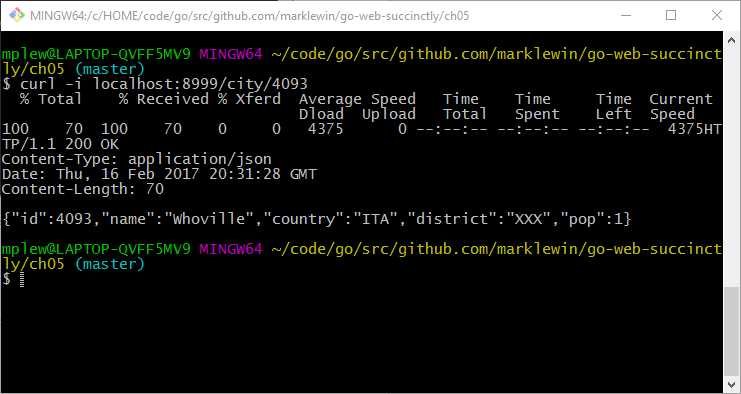

The record should be added to the database and you should receive the new record ID in the response, as in Figure 27.

Figure 26: Adding a New City

In the previous example, the ID of my recently added record is 4093. Yours is probably different. Rather than query the database again manually in order to see if the new record exists, you can simply use the following:

curl -i localhost:8999/city/4093

However, take care to replace 4093 with whatever ID was assigned when you added the city.

Figure 27: Verification—New City Added to the Database

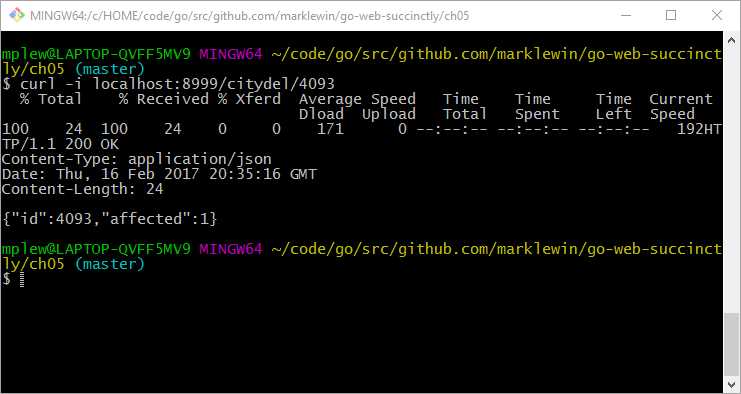

Deleting a city

In order to delete a city, you use a syntax similar to your search for a city by ID. Try using the same city ID that you just added to the database. For example:

curl -i localhost:8999/citydel/4093

If everything proceeds according to plan, you should get a DBUpdate object encoded as JSON, which shows that a single row is affected, as in Figure 29.

Figure 28: Deleting a City

Congratulations! You have just written your first “real” web service using Go.

Of course, this is far from perfect, and if you were planning to put it into production, you would probably want to do a fair bit of refactoring, implement better error handling, and so on.

However, the point of all this is to emphasize that Go is an excellent language for working on this type of application. I’ve done similar work in other languages, including Node.js and Ruby, and I am much happier working in Go. Everything seems more tidy and better thought out, in my humble opinion.

Challenge step

If you’re up for a challenge, try to implement update functionality in the application—that is, to put the U back into CRUD!

For starters, allow the client to submit a JSON city object that will first delete the existing record (if there is a matching city ID), then add a new one and report success (or otherwise) in JSON format, too.

Next, allow the client to submit some partial JSON along with the ID, then simply update an existing record based on the fields that have changed. For example, the client might submit the following:

{"id":4088,"name":"Whereville”,pop":2}

This will only update the Name and Population fields in the City table.

- 1800+ high-performance UI components.

- Includes popular controls such as Grid, Chart, Scheduler, and more.

- 24x5 unlimited support by developers.