CHAPTER 10

Standard Packages

One of the cardinal rules of programming is to reuse code whenever and wherever possible. Why spend time writing code for everyday situations when a bunch of crazily clever people have already done so (and have seen the fruits of their labors tried and tested in the wild)?

So let’s have a look at a few of the standard packages that ship with Go. These cover common scenarios that programmers face all the time.

Bear in mind, however, that this is only the tip of the iceberg. I can’t hope to cover all the standard packages in Go, or even all features from specific packages. To discover more, use your old friend godoc package_name.

The net/http package

We saw some of the capabilities of the net/http package in the previous chapter. However, net/http provides a full HTTP client and server implementation. For example, creating a working web server takes just a few lines of code:

Code Listing 49

package main import ( "fmt" "net/http" ) func handler(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) { fmt.Fprintf(w, "Hello, %s!", r.URL.Path[1:]) } func main() { http.HandleFunc("/", handler) http.ListenAndServe(":8080", nil) } |

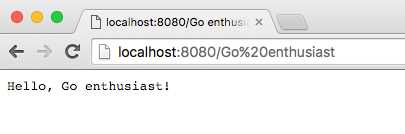

Figure 7: A Working Web Server in a Few Lines of Go

There’s much, much more to net/http. Look out for my forthcoming book, Go Web Development Succinctly, for a deep dive into net/http.

You can also see more about the net/http package here.

Input and output

A very common requirement in any language is the ability to read from and write to files. Go covers this with the io and io/util packages on the I/O end of things, and the os package to work with files in an operating system-specific manner and provide other operating system functionality.

In fact, you can read and write files with just the functions in the os package, but io and io/util provide a nice wrapper around these for easy use. Augment these with bufio functions for buffered reads and writes.

See the following links for more information:

Code Listing 50

package main import ( "io/ioutil" "os" ) func main() { // Write a new file from a byte string name := "test.txt" txt := []byte("Not much in this file.") if err := ioutil.WriteFile(name, txt, 0755); err != nil { panic(err) } // Read the contents of a file into a []byte results, err := ioutil.ReadFile(name) if err != nil { panic(err) } println(string(results)) // Or use os.Open(filename) reader, err := os.Open(name) if err != nil { panic(err) } results, err = ioutil.ReadAll(reader) if err != nil { panic(err) } reader.Close() println(string(results)) } |

Note: A common use of panic() is to abort if a function returns an error value that we cannot (or, in this example, will not) handle.

Strings

Programmers manipulate strings all the time. We saw some of the things we could do with strings in Chapter 5, but for a heap of new capabilities, look at the strings package.

Code Listing 51

package main import ( "fmt" "strings" ) func main() { fmt.Println( // does "test" contain "es"? strings.Contains("test", "es"), // does "test" begin with "te"? strings.HasPrefix("test", "te"), // does "test" end in "st"? strings.HasSuffix("test", "st"), // how many times is "t" in test? strings.Count("test", "t"), // at what position is "e" in "test"? strings.Index("test", "e"), // join "input" and "output" with "/" strings.Join([]string{"input", "output"}, "/"), // repeat "Golly" 6 times strings.Repeat("Golly", 6), /* replace "xxxx" with the first two non-overlapping instances of "a" replaced by "b" */ strings.Replace("xxxx", "a", "b", 2), /* put "a-b-c-d-e" into a slice using "-" as a delimiter */ strings.Split("a-b-c-d-e", "-"), // put "TEST" in lower case strings.ToLower("TEST"), // put "TEST" in upper case strings.ToUpper("test"), ) } |

true true true 2 1 input/output GollyGollyGollyGollyGollyGolly xxxx [a b c d e] test TEST

See more of the strings package here.

Errors

We’ve already seen error messages in Go, but what we don’t know yet is that we can create our own errors using the New() function in the errors package.

The fmt package formats an error message by implicitly calling its Error() method, which returns a string.

Code Listing 52

package main import ( "errors" "fmt" ) func main() { err := errors.New("error message") fmt.Println(err) } |

error message

See more about the errors package here.

Containers

If you come to Go from a language like Java, you might be surprised by the limited number of composite types. In vanilla Go, we have only maps, slices, and channels.

If none of these are suitable for your purposes, check out the container package, which introduces three more containers:

- list: an implementation of a doubly linked list that uses the empty interface for values

- ring: an implementation of circular “list”

- heap: an implementation of a “mini heap” in which each node is the “minimum” element in its sub-tree

Code Listing 53

package main import ( "container/heap" "container/list" "container/ring" "fmt" ) // following are for container/heap type OrderedNums []int func (h OrderedNums) Len() int { return len(h) } func (h OrderedNums) Less(i, j int) bool { return h[i] < h[j] } func (h OrderedNums) Swap(i, j int) { h[i], h[j] = h[j], h[i] } func (h *OrderedNums) Push(x interface{}) { *h = append(*h, x.(int)) } func (h *OrderedNums) Pop() interface{} { old := *h n := len(old) - 1 x := old[n] *h = old[:n] return x } // end declarations for container/heap func main() { // *** container/list *** l := list.New() e0 := l.PushBack(42) e1 := l.PushFront(11) e2 := l.PushBack(19) l.InsertBefore(7, e0) l.InsertAfter(254, e1) l.InsertAfter(4987, e2) fmt.Println("*** LIST ***") fmt.Println("-- Step 1:") for e := l.Front(); e != nil; e = e.Next() { fmt.Printf("%d ", e.Value.(int)) } fmt.Printf("\n") l.MoveToFront(e2) l.MoveToBack(e1) l.Remove(e0) fmt.Println("-- Step 2:") for e := l.Front(); e != nil; e = e.Next() { fmt.Printf("%d ", e.Value.(int)) } fmt.Printf("\n") // *** container/ring *** // create the ring and populate it blake := []string{"the", "invisible", "worm"} r := ring.New(len(blake)) for i := 0; i < r.Len(); i++ { r.Value = blake[i] r = r.Next() } // move (2 % r.Len())=1 elements forward in the ring r = r.Move(2) fmt.Printf("\n*** RING ***\n") // print all the ring values with ring.Do() r.Do(func(x interface{}) { fmt.Printf("%s\n", x.(string)) }) // *** container/heap h := &OrderedNums{34, 24, 65, 77, 88, 23, 46, 93} heap.Init(h) fmt.Printf("\n*** HEAP ***\n") fmt.Printf("min: %d\n", (*h)[0]) fmt.Printf("heap:\n") for h.Len() > 0 { fmt.Printf("%d ", heap.Pop(h)) } fmt.Printf("\n") } |

*** LIST ***

-- Step 1:

11 254 7 42 19 4987

-- Step 2:

19 254 7 4987 11

*** RING ***

worm

the

invisible

*** HEAP ***

min: 23

heap:

23 24 34 46 65 77 88 93

See the following links for more information:

Hashes and cryptography

Hashing involves applying a hashing algorithm to a data item, known as the hashing key, to create a hash. Hashes are used so that searching a database can be done more efficiently, data can be stored more securely, and data transmissions can be checked for tampering. Programmers use hashes a lot.

Go provides support for hashes in its hash and crypto packages. The difference between the hashes created by the hash package and those created by crypto is that the latter are much harder to reverse and are therefore more suitable for sensitive data.

The hashing algorithms supported are adler32, crc32, crc64, and fnv.

Code Listing 54

package main import ( "fmt" "hash/crc32" "io" "os" ) func hash(filename string) (uint32, error) { // open the file f, err := os.Open(filename) if err != nil { return 0, err } // always close files you have opened defer f.Close() // create the hashing algorithm h := crc32.NewIEEE() // copy the file into the hasher /* - copy() parameters are destination,source. It returns the number of bytes written, error */ _, err = io.Copy(h, f) // did this work? if err != nil { // no - return zero and the error details return 0, err } // yes, return the checksum and a nil error return h.Sum32(), nil } func main() { // contents of file1.txt: "Have I been tampered with?" h1, err := hash("file1.txt") if err != nil { return } // contents of file2.txt: "I have been tampered with!" h2, err := hash("file2.txt") if err != nil { return }

if h1 == h2 { fmt.Println(h1, h2, "Checksums match - files are identical") } else { fmt.Println(h1, h2, "Checksums don't match - files are different") } } |

2407730152 3829883431 Checksums don't match - files are different

See the following links for more information:

- 1800+ high-performance UI components.

- Includes popular controls such as Grid, Chart, Scheduler, and more.

- 24x5 unlimited support by developers.