CHAPTER 3

Let’s Go!

The Golang website

The Golang (short for Go Programming Language) website is your go-to resource (sorry, couldn’t resist) for all things related to Go. From here, you can download the Go compiler and tools, access online documentation, and read all about what’s new and wonderful in the world of Go.

Check it out now. Visit the Golang website and introduce yourself to the Go Gopher, who is the iconic mascot for the Go project. (And if you are really interested in the history behind the Go Gopher, read this post on the Go project blog.)

Figure 1: The Golang Homepage

Your first Go program

You don’t even need to install Go to write your first Go program because you can try out Go directly from the Golang website. Let’s do that now. After all, you might hate Go. I’d be very surprised and disappointed if you did, but I don’t want to be the guy responsible for making you install lots of cruft on your machine that you’ll never actually use. I’ll leave it to the PC vendors to do that!

First, visit the Go Playground.

Next, select everything in the code window and delete it.

Then, type the following as the first line of your new Go program:

package main

That’s it. No semicolons or other terminators required. But Go is a C-like language, and C and its derivatives use semicolons to tell the compiler where one line ends and another begins. Go uses semicolons too, but except for a few control structures, they don’t usually appear in the source code. Instead, the lexer inserts them automatically as it scans your program looking for new lines and inferring the end of statements from the tokens it finds, which means you don’t have to worry about terminating your statements. That’s just one of the many things that Go does to make your life easier.

That package statement you just entered tells the Go compiler that this code file will live in the main package. Go organizes code into packages, and the most important package of all is main, because that’s where your program will start. There are packages you write yourself, such as this one, and packages that you import from other sources.

Within the main package is a function called main(), which should come as no surprise if you have ever written any C or Java code. This is the entry point for your program.

So, press the return key a couple of times and enter:

func main() {

}

We’re going to write a simple program that writes a “Hello, world!” message to the screen. To do that, we need to import a package from the Go standard library called fmt. In between your package declaration and your main() function, enter the following:

import (

"fmt"

)

Now go back to your main() function and enter the following statement:

fmt.Printf("Hello, World!\n")

That line of code uses the Printf() function in the fmt package to display a line of text on the screen that is terminated by a new line character ('\n').

Let’s run it and see if it works. Just click the Run button at the top of the page and check the program output at the bottom. If you see your “Hello World!” message, your program is working fine. If not, compare your code to the screenshot in Figure 2.

Figure 2: The “Hello, world!” Program in the Go Playground

If everything worked as planned, your program was compiled on Google’s servers and executed, displayed the “Hello, World!” message, and then exited. This process is extremely fast because Go’s compiler is highly optimized. Yes, your program is only a few lines long and pretty trivial, but as you start to write more sophisticated code, the Go compiler will surprise you at just how fast it is—especially if you are a Java programmer.

I am reminded of an old joke at Java’s expense here:

“Knock! Knock!”

“Who’s there?”

“…”

“…”

“…”

“…”

“…”

“… Java!”

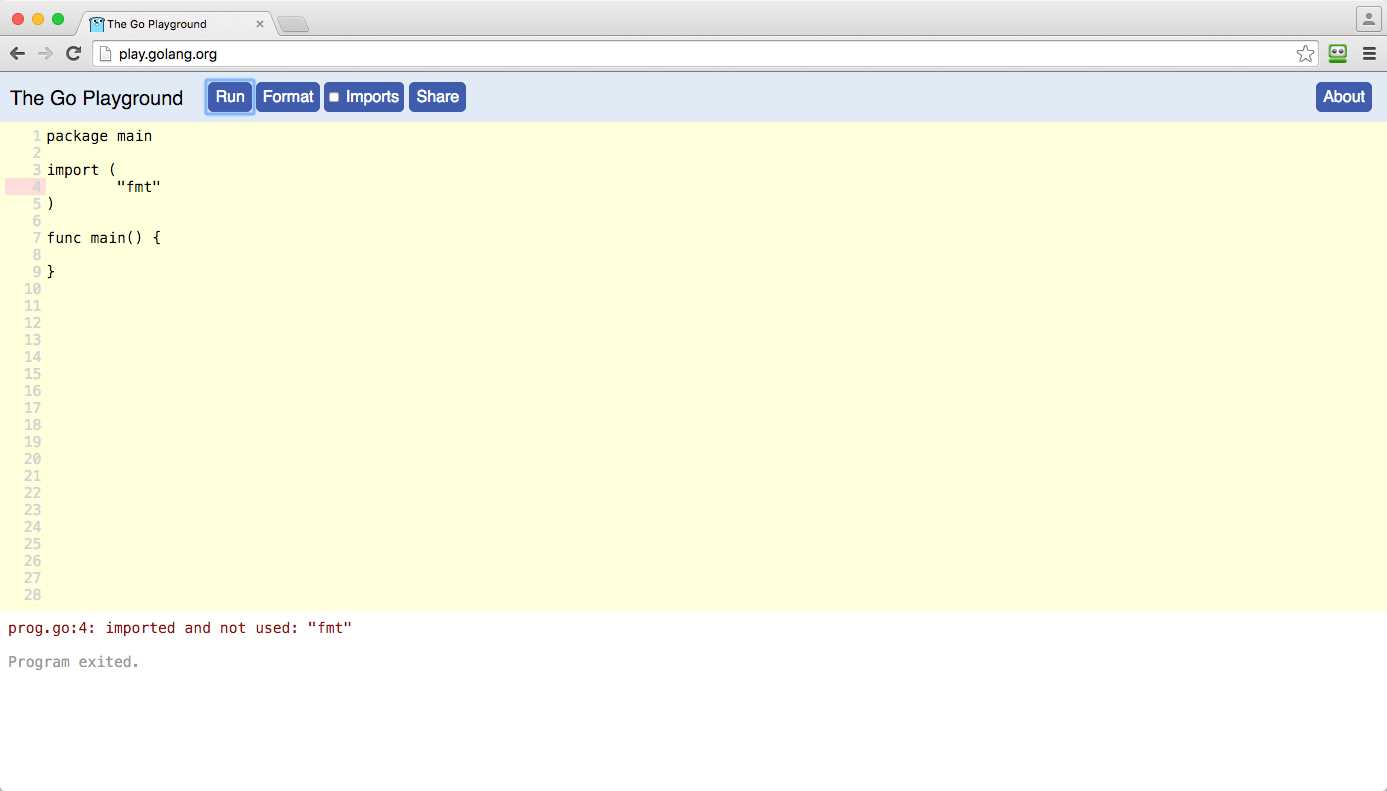

Now, I’d like you to break a couple of things just to get an idea of how Go works. First, delete the fmt.Printf() statement and run the program again. This time you should see an error, as shown in Figure 3. You’ll see the culprit line number highlighted in pink and an error message at the bottom.

Figure 3: Unused Package Error

This is because Go, unlike many languages, keeps a strict eye on the packages you import and how they are used in your program. Go doesn’t like you importing packages that you never use. It considers that a waste of resources and hates it so much that it raises an error. This keeps your programs nice and lean—not bloated by linked code that is never used.

Retype the line of code that prints the “Hello World!” message to your screen, but this time use a lowercase p for printf() and run the program again.

Figure 4: Unknown Function Error

The Go compiler throws another error. That’s because Go is a case-sensitive language, and it won’t forgive you if you get the capitalization wrong.

Fix up your program so that it’s working correctly.

Another thing to know about Go is the way it deals with strings. In most languages, strings are just a bunch of bytes. In Go, they are “runes,” which are really just integer values mapped to their Unicode counterparts. This makes it very easy to include foreign language characters in Go strings (and you can even use them in function names if you are so inclined).

For example, if we wanted to write “Hello, World!” in Telegu, we don’t need to do anything special to our code:

Figure 5: “Hello, World!” in Telegu

The Go Playground is a great place to experiment with the language, and you can even share the results of your labors with others (just click the Share button). However, as soon as you are ready to write something more substantial, you’re going to need to download the tools you require to compile and execute code on your local machine.

Setting up your machine

There are a few things you need to set up on your machine before you’re ready to start writing Go programs. The exact steps will depend on your operating system.

Text editor

You’ll need an editor in which to write your code. Any editor will do, but if you can find one that supports syntax highlighting for Go, it will make life easier. You might have to do some Googling to find the appropriate syntax highlighting language packages for your chosen editor, but doing so will be worth it.

Atom or Sublime Text are very good cross-platform editors and have all sorts of add-ins you can use to compile and format your code. The old diehards emacs and vim are equally, if not more, capable. Ultimately, it’s up to you which text editor you use because Go itself doesn’t care.

If you’re familiar with a certain IDE, you might be able to adapt it to use Go. For example, the IntelliJ IDEA platform has a plugin called go-ide.

I’m keeping things simple here and simply using a fairly simple text editor called TextWrangler on my Mac. It’s not exciting, but it doesn’t get in the way, either. Equivalent programs for Windows could be Notepad++, Notepad2, and PSPad, or, for Linux, Gedit, Geany, or Kate.

The terminal

The Go compiler and other tools are command-line applications, so you’ll need access to a terminal program unless your fancy-schmancy editor can run the tools directly. This might be good when you’re familiar with Go, but I’d suggest doing things via the command line when you’re starting out because this gives you a better idea of how the tools work.

Windows

In Windows, you can open the terminal (or command prompt as it’s known) by bringing up the Run dialog (hold down the Windows logo key+R) and then typing cmd.exe.

OS X

On a Mac, open Finder and navigate to Applications > Utility > Terminal. Pin it to the dock, because you’ll be using it a lot in this book.

Linux

If you’re running Linux you are doubtless familiar with the command line already and don’t need any help from me.

The Go toolset

You can download the Go tools from the Golang website. Find the picture of the gopher (it’s very hard to miss) and click on the Download Go button beneath it. Choose the version for your operating system from the “Featured Downloads” section. The current stable release of Go at the time of writing is 1.6, and all samples in this book are based upon this version. However, Google wants Go code to work across versions, so everything should still work if your version of Go is not the same as mine.

If you’re on Windows or OS X, you can simply run the installer and you’re good to go.

If you’re on Linux, you can extract the .tar.gz file to /usr/local/go and no further setup is required. If you insist on installing it somewhere else, you’ll need to set the $GOROOT environment variable accordingly. Consult the README.md file within the installer package for full instructions.

Test the installation by opening a terminal prompt and typing go. You should see a similar output to what is shown in Figure 6. When you run go without any other arguments, it simply lists the various tools and help available. You can see from the output that there are tools within the toolset for compiling, running, and formatting Go code; looking up documentation; and all the other tasks you will encounter as a Go programmer.

Figure 6: Checking the Installation of the Go Toolset

The Go workspace

In most programming environments, every code project has a separate workspace, each of which may be under source control. Go takes a different approach in that Go programmers usually keep all their Go code in a single workspace. Getting the structure of your workspace just right is important because the Go toolset expects things to be in certain places and gets very upset when you do things differently.

A Go workspace is simply a directory that contains three main subdirectories:

- src: Contains your Go source code files

- pkg: Contains packages

- bin: Contains executable programs

In practice, there will be further divisions within the src directory that map to different version control repositories, but for now we’re going to keep things very simple.

Create a location on your machine for all your Go projects. This will be your workspace. For example, mine is in the /Code/Go folder within my home directory (~/Code/Go). The only requirement is that this must not be in the same path as your Go installation.

The Go tools need to know where to find your code, and they’ll use an environment variable called GOPATH to do this. The GOPATH environment variable points to your Go workspace.

Use the following operating system-specific instructions to set the GOPATH. These are based on my environment, so you’ll need to change /Code/Go to reflect the location of your own workspace.

Windows

Open the command prompt and type the following:

setx GOPATH %USERPROFILE%\Code\Go

This sets GOPATH to C:\users\username\Code\Go on more recent versions of Windows. Older versions might not support this command-line approach, but you can also set GOPATH from within the Control Panel (System > Advanced > Environment Variables).

OS X and Linux

You’ll want to store the GOPATH setting so that your terminal remembers it. You usually do this in ~/.bash_profile. Enter the following command at the terminal:

echo 'export GOPATH=$HOME/<path to my folder>…' >> ~/.bash_profile

Exit the terminal, restart it, and enter the following command to ensure that the GOPATH setting has been persisted:

env | grep GOPATH

This should display the current value of the GOPATH environment variable.

Migrating “Hello, World!”

Let’s take the “Hello, World!” program we created in the Go Playground and get it working on our local machine.

First, within the workspace directory, create a new subdirectory called src and also one beneath it called hello. Bear in mind that the directory paths you need might differ from mine if your workspace is in a different location.

Windows

md src\hello

OS X and Linux

mkdir –p src/hello

Within /src/hello, create a file called main.go. Note that you can call this file whatever you like, but because it is the location of our main() function, main.go seems as a good a name as any.

Enter the “Hello, World!” code from the Go playground into the main.go file in your text editor of choice and save it.

Code Listing 1

package main import ( "fmt" ) func main() { fmt.Printf("Hello, world!\n") } |

In order to run the program, you will need to use the go tool. Open your terminal, change to the src/hello directory, and enter the following command:

go run main.go

This command compiles the main.go file and, if it is successful in doing so, launches it. If your program displays “Hello, world!” in your terminal that means you have succeeded. Give yourself a pat on the back. If it fails, look at the errors generated by the compiler and try to fix them in your code before executing go run main.go again. If you manage it, give yourself an extra pat on the back for your debugging skills.

Tip: For more information on setting up your workspace and the many different compiler options available, see the excellent documentation on these topics here.

Formatting Go source code

Unlike many languages, Go is very picky about how you format your code. This gives you less of a chance to show off your artistic nature, but it does prevent arguments during code reviews at work and makes your code (and everyone else’s) easier to read and, therefore, to maintain.

Go code has rules (that you must obey) and conventions (that they want you to obey). This is very different from Java and other languages derived from C. One of the biggest shocks programmers from these languages discover when they come to Go is how Go enforces rules on the use of curly braces.

In C and Java, when you have a block of code as part of a function or control structure (if, for, etc.), these are contained by curly braces. The C or Java compilers don’t care whether the initial brace appears. For example:

function myFunction() {

if (loggingEnabled == true) {

log.output("I'm in myFunction()");

}

…

}

This code can equally be written like this:

function myFunction()

{

if (loggingEnabled == true)

{

log.output("I'm in myFunction()");

}

…

}

But not in Go. Go insists that the opening brace is always on the same line as the statement preceding it. Most C and Java programmers use this style anyway, but they are surprised when Go raises an error if they depart from it.

Go also complains about the omission of curly braces when the body of a control structure contains only one line of code. Go insists upon it. For example, the following approach is illegal in Go:

if zombieApocalypse == true

fmt.Println("Run for the hills")

Instead, it should be written as:

if zombieApocalypse == true {

fmt.Println("Run for the hills")

}

Where there are no rules there are conventions, such as:

- Go uses tabs rather than spaces to indent code.

- When you import multiple packages using an import statement, Go likes them to be in alphabetical order.

- When you create custom types, Go likes the field names and types to be lined up nicely.

Because these conventions are hard to remember at first, and because the creators of Go want to make it easy for you to adopt their programming style, there is a tool called fmt in the toolset you can use to ensure that your code is very “Go-like.”

Execute the tool from the command line as follows:

go fmt /path/to/your/package

For example, if this is the source file (hello.go):

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

i := 5

fmt.Println((i))

fmt.Printf( "hello, world\n" )

}

Then, after running go fmt hello.go, the output will appear as follows:

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

i := 5

fmt.Println((i))

fmt.Printf("hello, world\n")

}

Much nicer!

It’s good to get into this habit, especially when working on projects with other coders who will expect your code to be formatted the “Go way.” You can include it in your build process, and some editors have plugins that can automatically format your code each time you save a source file.

Getting help with Go

No matter how great a coder you are, you can’t be expected to remember every intricacy of a programming language, even one as concise as Go. You’re going to need help, and the help documentation in Go is very useful.

There are two main ways to access help. First, you can visit the Documents link on the Golang website. It contains an introduction, how-to guides and articles, and comprehensive reference documentation. You can also catch up on the latest Go news with the Go blog and listen to a number of recorded talks and presentations about Go. Also check out the forums, mailing lists, and IRC channels available here.

You can also look up information about Go commands directly in Go itself. For example, to get information about the entire fmt package, enter the following at a terminal prompt:

godoc fmt

To drill into information about a particular Go type, variable, constant, or a function such as Printf(), enter the following:

godoc fmt Printf

If the documentation doesn’t provide the answers you need, because Go is an open source project, which means you can go directly to the source code itself. However, I think you’ll be pleased with the quality of the Go documentation.

Documenting your own code

You can also use the godoc tool to document your own packages. While this is beyond the scope of this book, all it requires are comments within your code, formatted in special ways depending on the type of information you are trying to impart. The syntax for creating comments in Go is the same as other C-style languages:

// This is a line comment that will be ignored by the compiler

/* This is a block comment.

It can span several lines and

will also be ignored by the compiler. */

Get into the habit of adding comments to your code. It’s useful for other programmers, and also for you when you revisit code you wrote a while ago and no longer understand it!

That concludes our crash course in writing, compiling, running, and getting help with Go code. In subsequent chapters, we’ll dig into the features of the language itself.

Recommended Go tool: Golint

This is another tool that I find very useful. It’s not part of the standard toolset, but can be installed from GitHub.

Golint is a linter for Go source code. It differs from go fmt in that go fmt reformats source code, whereas Golint generates a list of what it perceives to be style misdemeanors. I find I learn more about what Go expects from me stylistically when it tells me what’s wrong instead of just reformatting my code for me.

Install Golint by running:

go get github.com/golang/lint/golint

For usage instructions, refer to the online documentation.

- 1800+ high-performance UI components.

- Includes popular controls such as Grid, Chart, Scheduler, and more.

- 24x5 unlimited support by developers.