CHAPTER 1

Git – A Brief Overview

Although this book is focused on GitHub, there are some basic concepts and terms from Git that will be helpful to understand as you learn GitHub.

Working directory

The working directory is a folder on your computer or on a network share. Each developer has a complete copy of all of the code and associated files. You can do all your development work in the working directory, and let Git manage the version control aspects for that folder.

Git refers to this working directory as a repository, or a repos for short. When Git manages the folder, you get all the version control benefits that Git offers.

Git files

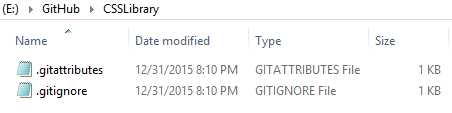

Within the working directory, you might find some extra files that are used to provide instructions to Git about the files in the folder. These are .gitattributes and .gitignore. The attribute file tells Git how to handle various files for comparison operations. The ignore file instructs Git that certain files (based on extension) should not be handled by Git. These files will be covered in more detail in a later chapter.

Figure 1: Starting Git empty working directory

When you create a repository, Git will add default versions of these files to your working directory. You can create a Git repository on an existing directory or have Git create a new repository (and working folder) for you. You can also clone an existing repository. A clone is a complete copy (including history) of the repository. No matter how you create it, you will now have a Git repository to start working in.

Clone

A clone is a complete copy of a repository. For example, you might make a copy of the repository, fix a few bugs, and then commit the code back to the repository. This assumes that you have write access to the repository however.

Fork

A fork is a copy of the repository created under your account for repositories that you cannot directly update. You can make your code changes in your copy, and then submit a pull request, asking your changes to be integrated back into the main repository. This is often the case on open source projects, where many collaborators help the author with issues, but the author decides when to include them in the main branch.

Pull request

A pull request is a request to the repository owner to merge your proposed changes back into the code base. This is usually done by a collaborator who has fixed a reported issue.

Note: Pull/push terminology can be confusing. “Push” typically means moving information from a central location to subscribers, while “pull” means the subscribers request the information. In GitHub, the “subscriber” is the repository owner, who will want to pull changes from your (developer) local repository. If you view the owner as a subscriber, the definition of “pull request” means: “Hey, subscriber, I have some changes you might like…”

Branches

A branch is a complete set of the repository files. Git creates a master branch by default. You can create additional branches to test out development ideas without impacting the master branch. Git allows you to compare code between branches, and at some point, to merge code from the “dev” branch back into the master branch. This allows multiple collaborators to work on a project without interfering with the base code.

Common branches might include:

- Feature branch: A branch dedicated to adding new features to the code base

- Release branch: The branch with code planned for next release

- Master branch: The default branch that all code eventually gets merged to

- Dev branch: The active development branch, where code is being work on

It’s up to you as to how to create branches, or even if you want to. However, if many collaborators are working on project, branches make it easier to develop enhancements without losing the ability to build a release from the main branch.

Tracked files

Tracked files are files in the working directory (repository) that Git manages. As you add new files or make updates to existing files, Git tracks these changes. At some point, you will want to add these files to the repository via the commit command.

Commit

Commit is the process of adding any changes in tracked files to repository. You will enter a summary and description, then add the files to the repository. Git will maintain a history of all commits against a repository.

Commit message

The commit message is a summary and description applied to the current set of files being committed to the repository.

Merging

Merging is the process of combining code from one branch to another. After the fixes and enhancements in a branch are completed, you will typically want to merge the code back into the master branch. Git provides differential tools to show the code changes and assist with the merge process.

Change sets

Git allows you to view all the changes you’ve made compared to the branch you are using. You can review the changes and decided which file changes you would like to commit to the branch. For example, you might have completed work on two out of five files you’ve changed, and you’d like to commit them separately. Git will report changes in all five files. You commit the two files, and Git adds them to history, while still tracking the other files. This allows you to create logical change sets, rather than simply date-based changes.

Commit history

Git keeps a history log of all committed changes, so you can review the changes made in any prior commits. If you’ve cloned a repository, you will have the commit history from that repository as well.

Summary

The basic Git flow is to create a repository, and make your changes and additions. Then, commit as many change-sets as you’d like. Git will report changes to your tracked file and allow you to decide how to organize your commits. Once you’ve done a number of commits, you can use Git’s commit history to view project status.

- 1800+ high-performance UI components.

- Includes popular controls such as Grid, Chart, Scheduler, and more.

- 24x5 unlimited support by developers.