CHAPTER 6

Specifying a Fake’s Behavior

In order for any configured fake to be useful, we’re going to want to control something about it. By specifying behavior on the configured fake, we’ll be able to test all possible execution paths in our SUT, because we control the dependencies injected into the SUT by using FakeItEasy.

Return Values

Returning values will be one of the most common behaviors you’re going to want to control on your fake. Let’s explore a couple of commonly used ways to specify return values.

Returns

The Returns call is probably the most widely used call for specifying behavior on a fake. Let’s change our ISendEmail interface introduced in Chapter 5. To start with, let’s just have it define one method, GetEmailServerAddress:

Code Listing 29: The ISendEmail interface

Here is how to specify the return value of GetEmailServerAddress:

Code Listing 30: Returning a hard-coded value

Hard-coded values work fine, as well as any variables you’ve setup in your unit test:

Code Listing 31: Returning a variable set up in your unit test

Returns can also work with collections. Let’s add a GetAllCcRecipients method to our ISendEmail interface that returns a List<string> that represents any email addresses that we wanted to send an email to in our ISendEmail interface:

Code Listing 32: Adding GetAllCcRecipients to the ISendEmail interface

Here is the Returns call:

A.CallTo(() => emailSender.GetAllCcRecipients()).Returns(new List<string> { "[email protected]", "[email protected]" }); |

Code Listing 33: The Returns call for testing GetAllCcRecipients

We’re using hard-coded values here, but we could easily plug in a variable that is declared and populated in the test setup. Returns looks at the return type of the configured call, and forces you to provide something that matches the type.

Let’s take a look into a couple more useful ways to deal with return values next.

ReturnsNextFromSequence

Sometimes return values that are determined at runtime are not known at design time when using FakeItEasy. A fake of a type that implements IEnumerable would be an example. Another example would be calling into the same instance of a fake multiple times and getting a different result back each time in the same calling context for the SUT.

For situations like this, there is ReturnsNextFromSequence. For a more concrete look at this functionality, let’s again explore this call through an example. We’ll be using three separate interfaces for this sample.

We’re going to introduce an interface called IProvideNewGuids:

public interface IProvideNewGuids { Guid GenerateNewId(); } |

Code Listing 34: An abstraction to generating new IDs that are GUIDs

The role of this abstraction is very straightforward—it abstracts the creation of new globally unique identifiers (GUIDs) away from code that needs the functionality. This reason could be different ways to generate GUIDs based on environment, usage, etc; but again, this is sample code, so if this seems like an odd thing to abstract, bear with me until the end of the sample.

The next interface is ICustomerRepository:

public interface ICustomerRepository { List<Customer> GetAllCustomers(); } |

Code Listing 35: The ICustomerRepository interface

ICustomerRepository simply allows us to get a list of customers. The final interface, ISendEmail, allows us to send an email.

public interface ISendEmail { void SendMail(Email email); } |

Code Listing 36: The ISendEmail interface

Note that SendMail takes an Email object. Let’s look at Email:

public class Email { public Guid Id { get; set; } public string To { get; set; } } |

Code Listing 37: The Email class

Email takes an ID that is a GUID, and a string that represents a “To” address. For the sake of the example, let’s say that a requirement of the business is to be able to uniquely identify every single email sent in the system, even for the same customer. That being the case, the Id field takes a GUID, which we’ll populate whenever we send an email using ISendEmail.

Now that we have an idea of the dependencies involved in this example, as well as a business requirement, here is a CustomerService class that shows them in use:

public class CustomerService { private readonly ISendEmail emailSender; private readonly ICustomerRepository customerRepository; private readonly IProvideNewGuids guidProvider; public CustomerService(ISendEmail emailSender, ICustomerRepository customerRepository, IProvideNewGuids guidProvider) { this.emailSender = emailSender; this.customerRepository = customerRepository; this.guidProvider = guidProvider; } public void SendEmailToAllCustomers() { var customers = customerRepository.GetAllCustomers(); foreach (var customer in customers) { var email = new Email { Id = guidProvider.GenerateNewId(), To = customer.Email }; emailSender.SendMail(email); } } } |

Code Listing 38: The CustomerService class using all three dependencies

When we invoke SendEmailToAllCustomers, the method will reach out to the GetAllCustomers method on ICustomerRepository, and for each customer returned, create a new Email object using our IProvideNewGuids provider to populate the Id field. The code then uses the final dependency, ISendEmail, to send the email by calling SendMail and passing the Email object to it.

At the beginning of this section, I mentioned we can use ReturnsNextFromSequence to test values that are only available at runtime. Looking back over the sample code I just provided, can you find the value that will only be available at runtime? If you answered “the GUID being generated by the IProvideNewGuids dependency,” then you are correct.

Now that we’ve identified the values that we’ll have to deal with at run time, here is the unit test for the CustomerService class:

[TestFixture] public class WhenSendingEmailToAllCustomers { private readonly Guid guid1 = Guid.NewGuid(); private readonly Guid guid2 = Guid.NewGuid(); [SetUp] public void Given() { var customerRepository = A.Fake<ICustomerRepository>(); A.CallTo(() => customerRepository.GetAllCustomers()).Returns(new List<Customer> { new Customer { Email = "[email protected]" }, new Customer { Email = "[email protected]" } });

var guidProvider = A.Fake<IProvideNewGuids>(); A.CallTo(() => guidProvider.GenerateNewId()) .ReturnsNextFromSequence(guid1, guid2); var emailSender = A.Fake<ISendEmail>(); var sut = new CustomerService(emailSender, customerRepository, guidProvider); sut.SendEmailToAllCustomers(); } } |

Code Listing 39: Using ReturnsNextFromSequence

We provide the two GUIDs upfront in our test setup, then use those values in the ReturnsNextFromSequence call to the faked IProvideNewGuids dependency. When the CustomerService class loops through each customer returned by ICustomerRepository, a new Email will be created with each GUID in sequence. That Email will then be sent via ISendEmail to the correct customer email address.

Note: So far, we’ve only covered using FakeItEasy in test setup. You might be wondering where the assertions are for this unit test. Right now, since this chapter is focusing on specifying a fake’s behavior, we’re focusing on that in our test setup; we’re not ready to move into assertions yet. We’ll learn about Assertions using FakeItEasy in Chapter 7.

ReturnsLazily

ReturnsLazily is a very powerful method you can use to configure a fake’s behavior when ReturnsNextFromSequence won’t provide you with what you need. ReturnsLazily comes in handy when you’re trying to test code that returns different objects in the same call to the SUT. Let’s explore an example.

Let’s say we want to get a list of customer names as a CSV string given this interface definition:

public interface ICustomerRepository { Customer GetCustomerById(int id); } |

Code Listing 40: The ICustomerRepository interface

And this customer class:

public class Customer { public string FirstName { get; set; } public string LastName { get; set; } } |

Code Listing 41: The Customer class

Here is the implementation of a CustomerService class that shows how to do it:

public class CustomerService { private readonly ICustomerRepository customerRepository; public CustomerService(ICustomerRepository customerRepository) { this.customerRepository = customerRepository; } public string GetCustomerNamesAsCsv(int[] customerIds) { var customers = new StringBuilder(); foreach (var customerId in customerIds) { var customer = customerRepository.GetCustomerById(customerId); customers.Append(string.Format("{0} {1},", customer.FirstName, customer.LastName)); } RemoveTrailingComma(customers); return customers.ToString(); } private static void RemoveTrailingComma(StringBuilder stringBuilder) { stringBuilder.Remove(stringBuilder.Length - 1, 1); } } |

Code Listing 42: The CustomerService class

In the CustomerService class, you can see that we’re looping through each customerId supplied to the GetCustomerNamesAsCsv method and calling to our customerRepository to get each customer by Id in the foreach loop. We’re formatting the name to FirstName LastName, then using stringBuilder to append the formatted name into a comma-delimited string.

Note: There is a better way to implement the CustomerService class, which is to call ONCE to the repository for all customers you need, instead of making a separate repository call by for each customer by Id. This would result in fewer read calls to the database. Also, we could easily return the formatted customer’s first name and last name using a LINQ projection instead of picking it apart in the GetCustomerNamesAsCsv method using a StringBuilder. Because this code is illustrating how to use ReturnsLazily, we’ll keep it as-is for now.

And here is the unit test using ReturnsLazily:

[TestFixture] public class WhenGettingCustomerNamesAsCsv { private string result; [SetUp] public void Given() { var customers = new List<Customer> { new Customer { Id = 1, FirstName = "FirstName1", LastName = "LastName1" }, new Customer { Id = 2, FirstName = "FirstName2", LastName = "LastName2" } }; var employeeRepository = A.Fake<ICustomerRepository>(); A.CallTo(() => employeeRepository.GetCustomerById(A<int>.Ignored)) .ReturnsLazily<Customer, int>( id => customers.Single(customer => customer.Id == id)); var sut = new CustomerService(employeeRepository); result = sut.GetCustomerNamesAsCsv(customers.Select(x => x.Id).ToArray()); } [Test] public void ReturnsCustomerNamesAsCsv() { Assert.That(result, Is.EqualTo("FirstName1 LastName1,FirstName2 LastName2")); } } |

Code Listing 43: The unit test for the CustomerService class using ReturnsLazily

If the call to ReturnsLazily is leaving you scratching your head, let’s first examine the signature of ReturnsLazily that we’re using in this unit test.

// Summary: // Specifies a function used to produce a return value when the configured call // is made. The function will be called each time this call is made and can // return different values each time. // // Parameters: // configuration: // The configuration to extend. // // valueProducer: // A function that produces the return value. // // Type parameters: // TReturnType: // The type of the return value. // // T1: // Type of the first argument of the faked method call. // // Returns: // A configuration object. public static IAfterCallSpecifiedWithOutAndRefParametersConfiguration ReturnsLazily<TReturnType, T1>(this IReturnValueConfiguration<TReturnType> configuration, Func<T1, TReturnType> valueProducer); |

Code Listing 44: The ReturnsLazily overload

Note the ReturnsLazily<TReturnType, T1> is the opposite of how .NET Func delegate works; ReturnsLazily takes the return type (in this case, TReturnType) as the FIRST generic type instead of the last generic type. In the method definition, you can see the .NET Func delegate type specifying the TReturnType being passed in last. In this case, the TReturnType is a Customer.

Returning to the unit test code, we use A<int>.Ignored to configure the behavior on the GetCustomerById method, and instead, delegate how return values will be determined at runtime using ReturnsLazily.

Looking at our ReturnsLazily code:

.ReturnsLazily<Customer, int> (id => customers.Single(customer => customer.Id == id));

We’re returning a customer, and passing an int to the delegate that will figure out a customer to return for each time GetCustomerNamesAsCsv is invoked. In this case our delegate is a LINQ query against the List<Customer> setup in the unit test that will change the ID each time GetCustomerNamesAsCsv is invoked.

What‘s happening at runtime is that every time GetCustomerNamesAsCsv is invoked, we’re querying our customer list with the next available ID. Basically, the code is taking the next customer available in the list and using that as the return value from GetCustomerNamesAsCsv.

As you can see, ReturnsLazily can provide powerful functionality when testing a SUT’s method in which different objects are returned from a single call. Please explore the other overloads for this very useful operator.

Doing Nothing

There are times we want to do nothing. No, not you—the configured fake! Thankfully, FakeItEasy gives this to us out of the box.

First, let’s change our ISendEmail interface to:

public interface ISendEmail { void SendMail(); } |

Code Listing 45: The ISendEmail interface

And let’s change our CustomerService definition to:

public class CustomerService { private readonly ISendEmail emailSender; private readonly ICustomerRepository customerRepository; public CustomerService(ISendEmail emailSender, ICustomerRepository customerRepository) { this.emailSender = emailSender; this.customerRepository = customerRepository; } public void SendEmailToAllCustomersAsWellAsDoSomethingElse() { var customers = customerRepository.GetAllCustomers(); foreach (var customer in customers) { //although this call is being made, we don't care about the setup, b/c it doesn't directly affect our results emailSender.SendMail(); } } } |

Code Listing 46: The CustomerService class

A call to a non-configured fake will result in nothing happening. There are two ways to handle this.

One is to specifically tell FakeItEasy that the fake should do nothing:

[TestFixture] public class ATestWhereWeDontCareAboutISendEmailBySpecifyingDoesNothing { [SetUp] public void Given() { var customerRepository = A.Fake<ICustomerRepository>(); A.CallTo(() => customerRepository.GetAllCustomers()) .Returns(new List<Customer> { new Customer() });

var emailSender = A.Fake<ISendEmail>(); A.CallTo(() => emailSender.SendMail()).DoesNothing(); var sut = new CustomerService(emailSender, customerRepository); } } |

Code Listing 47: Explicitly telling FakeItEasy to do nothing

Here we explicitly tell FakeItEasy we want a call to SendEmail from the faked ISendEmail to do nothing. But like I said earlier, we get this behavior by default from FakeItEasy, so we could easily shorten the above unit test setup to the setup directly below.

[TestFixture] public class ATestWhereWeDontCareAboutISendEmail { [SetUp] public void Given() { var customerRepository = A.Fake<ICustomerRepository>(); A.CallTo(() => customerRepository.GetAllCustomers()) .Returns(new List<Customer> { new Customer() }); var sut = new CustomerService(A.Fake<ISendEmail>(), customerRepository); |

Code Listing 48: Pass A.Fake<ISendEmail> directly into CustomerService

Here you can see we’re using A.Fake<ISendEmail> directly as an argument when newing up CustomerService. We don’t have to tell FakeItEasy to DoNothing, we just pass in a newly created fake and let the behavior default to nothing.

The only time you will have to call DoNothing explicitly is if you’re working with a strict fake, which we’ll cover in the next section.

Strict

Simply put, specifying Strict on any created fakes forces you to configure them. Any calls to unconfigured members throw an exception. Let’s look at a quick example.

Code Listing 49: The IDoSomething interface

Let’s look at the how to configure a strict fake for IDoSomething:

[TestFixture] public class ConfigureAStrictFakeOfIDoSomething { [SetUp] public void Given() { var doSomething = A.Fake<IDoSomething>(x => x.Strict()); A.CallTo(() => doSomething.DoSomething()).Returns("I did it!");

var sut = new AClassThatNeedsToDoSomething(doSomething); var result = sut.DoSomethingElse(); } |

Code Listing 50: Configuring a strict fake of IDoSomething

In Code Listing 50, we create a strict fake of IDoSomething using x => x.Strict(). We configure a call to the DoSomething member on the fake. When we look at the SUT’s DoSomethingElse method, you’ll see that we’re invoking the DoSomethingElse method on the fake, which has not been configured in the test setup:

public class AClassThatNeedsToDoSomething { private readonly IDoSomething doSomething; public AClassThatNeedsToDoSomething(IDoSomething doSomething) { this.doSomething = doSomething; } public string DoSomethingElse() { return doSomething.DoSomethingElse(); } } |

Code Listing 51: The AClassThatNeedsToDoSomething is invoking a non-configured member on a strict fake

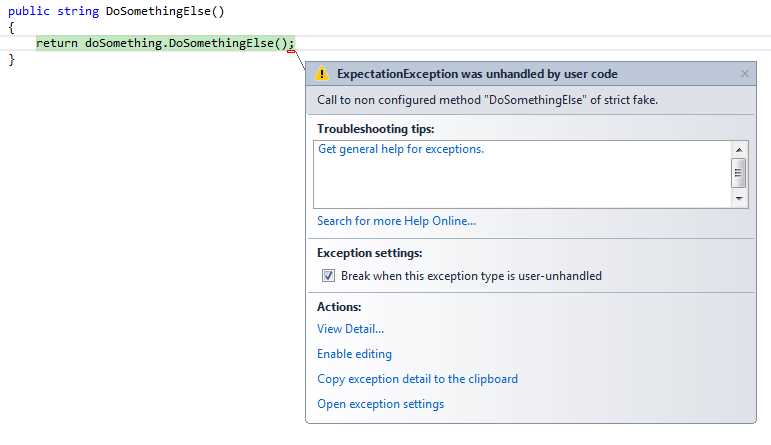

When we go to run this unit test, we’ll get this exception:

Figure 22: You cannot invoke a non-configured member of a strict fake

Exceptions

Sometimes we want to configure a call to throw an exception. This could be because of execution flow that changes in the SUT, depending on if the call succeeds or fails. Here is how to configure a fake to throw an exception. First, we have some code updates to our examples we’ve used so far.

Again, we’ll use the ISendEmail interface to start the example, but this time, our SendMail method will take a list of customers:

public interface ISendEmail { void SendMail(List<Customer> customers); } |

Code Listing 52: The ISendEmail interface

We’ll also use an ICustomerRepository interface to give us access to a list of all customers:

public interface ICustomerRepository { List<Customer> GetAllCustomers(); } |

Code Listing 53: The CustomerRepository interface

We’ve added a new class, named BadCustomerEmailException, that inherits from Exception to represent a bad customer email send attempt:

public class BadCustomerEmailException : Exception {} |

Code Listing 54: BadCustomerEmailException

The CustomerService class takes and ISendEmail dependency that is invoked via the SendEmailToAllCustomers method.

public class CustomerService { private readonly ISendEmail emailSender; private readonly ICustomerRepository customerRepository; public CustomerService(ISendEmail emailSender, ICustomerRepository customerRepository) { this.emailSender = emailSender; this.customerRepository = customerRepository; } public void SendEmailToAllCustomers() { var customers = customerRepository.GetAllCustomers(); try { emailSender.SendMail(customers); } catch (BadCustomerEmailException ex) { //do something here like write to a log file, etc... } } } |

Code Listing 55: Try/catch around the SendMail method of ISendEmail in the CustomerService class

In the SendEmailToAllCustomers method, we pass all the customers returned by the repository to the email sender. If there is a problem, we catch the BadCustomerEmailException.

And finally, our unit test:

public class WhenSendingEmailToAllCustomersAndThereIsAnException { [SetUp] public void Given() { var customerRepository = A.Fake<ICustomerRepository>(); var customers = new List<Customer>() { new Customer { EmailAddress = "[email protected]" } }; A.CallTo(() => customerRepository.GetAllCustomers()).Returns(customers); var emailSender = A.Fake<ISendEmail>(); A.CallTo(() => emailSender.SendMail(customers)) .Throws(new BadCustomerEmailException()); var sut = new CustomerService(emailSender, customerRepository); sut.SendEmailToAllCustomers(); } } |

Code Listing 56: The unit test for CustomerService

Note the use of Throws at the end of the A.CallTo line. This allows us to throw the exception from our ISendEmail fake and then write any unit tests that would need to be written for compensating actions.

Note: I’ve included a comment in the code in the catch block of the CustomerService.SendEmailToAllCustomers method, not an actual implementation. What you need to do here would depend on what you want to do when this exception is caught in your code; write to a log, write to a database, take compensating actions, etc.

Out and Ref Parameters

To illustrate how to handle Out and Ref parameters using FakeItEasy, let’s continue with the current example we’ve been using so far, using the ISendEmail and ICustomerRepository interfaces.

Instead of GetAllCustomers returning a List<Customer>, it will now use an out parameter to return the list:

public interface ICustomerRepository { void GetAllCustomers(out List<Customer> customers); } |

Code Listing 57: The list of customers is now an out parameter

The CustomerService class has changed as well. It no longer is using a try/catch block; it is calling GetAllCustomers from ICustomerRepository, and for each Customer returned, we send an email:

public class CustomerService { private readonly ISendEmail emailSender; private readonly ICustomerRepository customerRepository; public CustomerService(ISendEmail emailSender, ICustomerRepository customerRepository) { this.emailSender = emailSender; this.customerRepository = customerRepository; } public void SendEmailToAllCustomers() { List<Customer> customers; customerRepository.GetAllCustomers(out customers); foreach (var customer in customers) { emailSender.SendMail(); } } } |

Code Listing 58: The CustomerService class

Here is the updated unit test. Pay special attention to how FakeItEasy deals with the out parameter:

[TestFixture] public class WhenSendingEmailToAllCustomers { [SetUp] public void Given() { var customerRepository = A.Fake<ICustomerRepository>(); var customers = new List<Customer> { new Customer { EmailAddress = "[email protected]" } }; A.CallTo(() => customerRepository.GetAllCustomers(out customers)) .AssignsOutAndRefParameters(customers); var sut = new CustomerService(A.Fake<ISendEmail>(), customerRepository); sut.SendEmailToAllCustomers(); } } |

Code Listing 59: Using .AssignsOutAndRefParameters to test the out parameter

Here, you can see the use of AssignsOutAndRefParameters from the GetAllCustomers call.

Invokes

Sometimes a faked method's desired behavior can't be satisfactorily defined just by specifying return values, throwing exceptions, assigning out and ref parameters, or even doing nothing.

Invokes allows us to execute custom code when the fake’s method is called.

Let’s take a break from our current samples where we have been using the ISendEmail abstraction. To illustrate the usage of Invokes, I’d like to introduce another abstraction we’ll work with, IBuildCsv:

public interface IBuildCsv { void SetHeader(IEnumerable<string> fields); void AddRow(IEnumerable<string> fields); string Build(); } |

Code Listing 60: The IBuildCsv interface

This abstraction allows us to set a header for the CSV, add one to n rows to the CSV, and finally, call Build to return a CSV file based off the information we’re providing to both SetHeader and AddRow.

To put this abstraction to work, let’s first create a simple Customer class with FirstName and LastName properties:

public class Customer { public string LastName { get; set; } public string FirstName { get; set; } } |

Code Listing 61: The Customer class

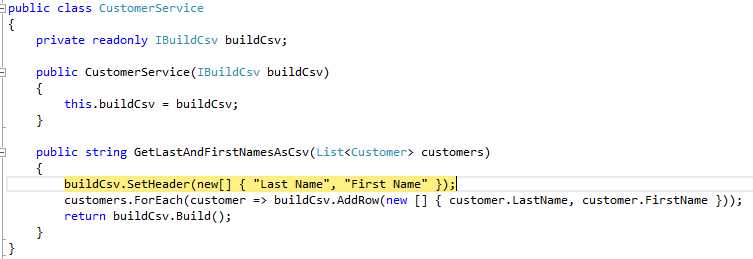

And to tie it all together, let’s create a CustomerService class that takes a list of customers, and from that list, returns a CSV file of “Last name, First name” using the IBuildCsv abstraction.

public class CustomerService { private readonly IBuildCsv buildCsv; public CustomerService(IBuildCsv buildCsv) { this.buildCsv = buildCsv; } public string GetLastAndFirstNamesAsCsv(List<Customer> customers) { buildCsv.SetHeader(new[] { "Last Name", "First Name" }); customers.ForEach(customer => buildCsv.AddRow( new [] { customer.LastName, customer.FirstName })); return buildCsv.Build(); } } |

Code Listing 62: The CustomerService class

Here you can see the buildCsv dependency being passed into the CustomerService class to build a CSV file from the provided list of customers passed to GetLastAndFirstNameAsCsv.

Now that we have all our items in usage, let’s write some unit tests. Let’s start with our unit test setup.

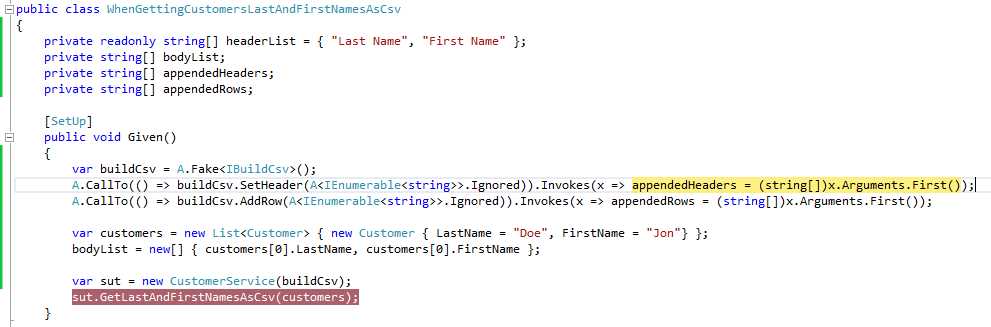

[TestFixture] public class WhenGettingCustomersLastAndFirstNamesAsCsv { private readonly string[] headerList = { "Last Name", "First Name" }; private string[] bodyList; private string[] appendedHeaders; private string[] appendedRows; [SetUp] public void Given() { var buildCsv = A.Fake<IBuildCsv>(); A.CallTo(() => buildCsv.SetHeader(A<IEnumerable<string>>.Ignored)) .Invokes(x => appendedHeaders = (string[])x.Arguments.First()); A.CallTo(() => buildCsv.AddRow(A<IEnumerable<string>>.Ignored)) .Invokes(x => appendedRows = (string[])x.Arguments.First());

var customers = new List<Customer> { new Customer { LastName = "Doe", FirstName = "Jon"} }; bodyList = new[] { customers[0].LastName, customers[0].FirstName }; var sut = new CustomerService(buildCsv); sut.GetLastAndFirstNamesAsCsv(customers); } |

Code Listing 63: Setup for the CustomerService class unit test using Invokes

Let’s talk about this unit test setup a bit. First, we’re doing regular setup items, like creating our fake, setting up some test data, creating the SUT, and finally, calling the SUT’s method, GetLastAndFirstNamesAsCsv.

What is different here is the configuration of our fake. Here we see the introduction of Invokes. Invokes requires a fair bit of explanation, so bear with me while I walk you through what’s happening when we setup our fake’s behavior to use Invokes.

When we use Invokes, we’re “hijacking” the method on our fake to execute custom code. If we hit F12 while our cursor is over Invokes in the IDE, we’ll see this definition:

public interface ICallbackConfiguration<out TInterface> : IHideObjectMembers { TInterface Invokes(Action<FakeItEasy.Core.IFakeObjectCall> action); } |

Code Listing 64: The definition of Invokes

Invokes is asking for an Action<T> where T is FakeItEasy.Core.IFakeObjectCall. But what is FakeItEasy.Core.IFakeObjectCall? If we use F12 to see its definition, this is what we’ll see:

public interface IFakeObjectCall { ArgumentCollection Arguments { get; } object FakedObject { get; } MethodInfo Method { get; } } |

Code Listing 65: The definition of IFakeObjectCall

Look at all the information available to us about the method of the fake. For brevity, we’ll only look at the ArgumentCollection Arguments {get;} property, because that’s what we’re using in our test setup. You should explore the other properties available here on your own.

Using F12 to get the definition of ArgumentCollection, you’ll see this:

[Serializable] public class ArgumentCollection : IEnumerable<object>, IEnumerable { [DebuggerStepThrough] public ArgumentCollection(object[] arguments, IEnumerable<string> argumentNames); [DebuggerStepThrough] public ArgumentCollection(object[] arguments, MethodInfo method); public IEnumerable<string> ArgumentNames { get; } public int Count { get; } public static ArgumentCollection Empty { get; } public object this[int argumentIndex] { get; } public T Get<T>(int index); public T Get<T>(string argumentName); public IEnumerator<object> GetEnumerator(); } |

Code Listing 66: The definition of ArgumentCollection

Here we see the ability to grab all sorts of information about the argument collection that is sent into the fake’s method. Through these methods and properties, our example uses the ArgumentCollection, and then via LINQ, takes the first of the collection.

Returning to our example, let’s break down this single line:

buildCsv.SetHeader(A<IEnumerable<string>>.Ignored)).Invokes(x => appendedHeaders = (string[])x.Arguments.First();

We call Invokes, then using an Action delegate, we assign the first argument of the fake’s method to a local variable called appendedHeaders that we declared in our test method.

So when this code is executed in CustomerService:

buildCsv.SetHeader(new[] { "Last Name", "First Name" });

The code we execute will be in our test setup and appendedHeaders will be populated with the argument value that was provided to SetHeader. In this case, this value is defined in the GetLastAndFirstNamesAsCsv method on our SUT.

For further illustration, let’s finish up our unit test and debug into one of the tests:

[Test] public void SetsCorrectHeader() { Assert.IsTrue(appendedHeaders.SequenceEqual(headerList)); } [Test] public void AddsCorrectRows() { Assert.IsTrue(appendedRows.SequenceEqual(bodyList)); } |

Code Listing 67: The test method for CustomerService

Here you can see that our assertions are very straightforward; we assert that the arrays we’re populating in the Invokes call in our test setup are equal to two lists we set up in our test setup.

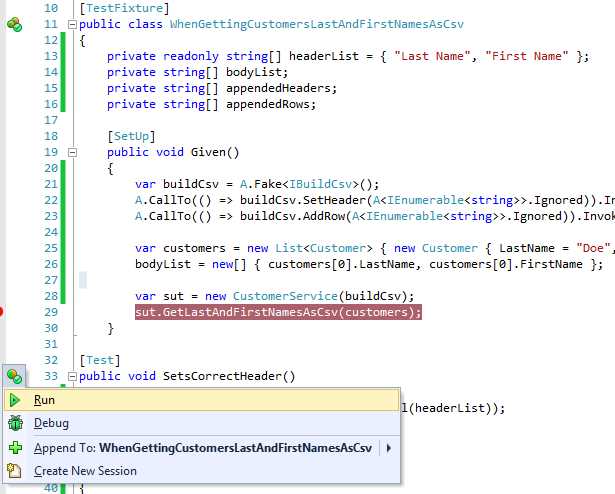

Let’s set a breakpoint on the line where our SUT’s method is invoked in our test setup, and select Debug on the first test method, SetsCorrectHeader

Figure 23: Put a breakpoint on sut.GetLastAndFirstNamesAsCsv and then select Debug in the ReSharper menu next to SetsCorrectHeader

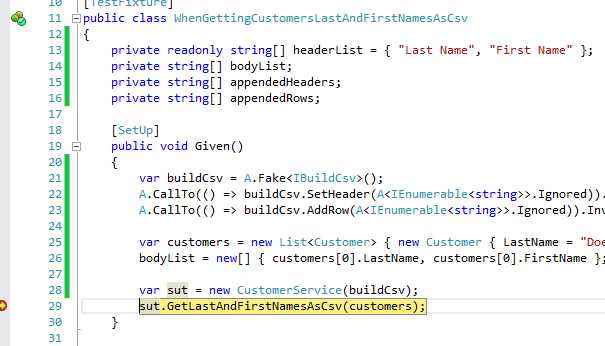

When you hit the breakpoint for sut.GetLastAndFirstNamesAsCsv, press the F11 key (step into), and press F10 once to stop execution on the first line of GetLastAndFirstNamesAsCsv:

buildCsv.SetHeader(new[] { "Last Name", "First Name" });

Figure 24: When you hit this breakpoint, press F11 (step into) to step into the GetLastAndFirstNamesAsCsv method

Now that we have our execution path stopped on this line, I want you to press F11.

Figure 25: Execution stopped at the first line of GetLastAndFirstNamesAsCsv

Surprise; we’re back in the test setup method where we called Invokes for SetHeader.

Figure 26: We’re back at our Invokes call in our test setup

What we’re seeing here is our custom code being invoked, which adds those header values into the appendedHeaders variable, which we’ll use in our test assertions.

If you’d like to keep following the execution path until this test passes, please go ahead. You’ll see how we’re bounced back for the call to AddRow as well. Our action we defined via Invokes will populate the local variables being used in our test setup so we can run our assertions correctly.

Summary

In this chapter, we have seen many different approaches to specifying a fake’s behavior. We started with the most commonly used behavior, Returns. From there, we looked into other scenarios using different forms of Returns, and then ended with how to deal with exceptions and out and ref parameters.

Although we’ve covered a good bit so far, we really still have yet to see the entire toolset of FakeItEasy used. Our unit tests have only covered test setup or very basic assertions, and our fake’s members have not dealt with arguments yet.

In order to get most out of FakeItEasy, we not only need to specify behavior, but we also need to deal with arguments to members on those fakes. We’ll explore Assertions in the next chapter.

- 1800+ high-performance UI components.

- Includes popular controls such as Grid, Chart, Scheduler, and more.

- 24x5 unlimited support by developers.