CHAPTER 5

Configuring Calls to a Fake

A.CallTo

Now that we know how to create a fake, it’s time to start specifying calls to configure on the fake. What does this mean? When we create a fake, we’re doing so with an explicit purpose to define some type of behavior we want or expect on the faked item. In order to get that desired behavior, we must configure the call.

We configure a call by invoking the CallTo method on the static A class:

A.CallTo(() => [theFake].[aFakesMember]) |

Code Listing 23: The CallTo method

theFake in Code Listing 23 is a fake we’ve configured. From there we should be able be able to specify which member on the fake to a call (aFakesMember). If you look at the IntelliSense presented to you when you type A.CallTo, you’ll see a number of overloads; let’s explore those overloads.

Exploring the Overloads

If we look at the overloads of CallTo in the IDE, we’ll see the following:

public static class A { public static IVoidArgumentValidationConfiguration CallTo(Expression<Action> callSpecification); public static IReturnValueArgumentValidationConfiguration<T> CallTo<T>(Expression<Func<T>> callSpecification); public static IAnyCallConfigurationWithNoReturnTypeSpecified CallTo(object fake); |

Code Listing 24: CallTo overloads

Don’t worry about the interfaces being returned from the CallTo methods for now, but instead, look at what the methods take. A.CallTo is the “gateway” to getting FakeItEasy to do anything. Let’s quickly explore each method call before continuing:

- CallTo (Expression<Action> callSpecification): We’ll use this CallTo overload to configure members that don’t return a value.

- CallTo<T> (Expression<Func<T>> callSpecification): We’ll use this CallTo overload to configure members that return a value.

- CallTo(object fake): This is the simplest signature of the three overloads. We’ll use this CallTo overload for faking a class’s members.

Note: Faking a class is covered in Chapter 9, “Faking the Sut.” For now, we’ll concentrate on the two overloads that take each of the .NET delegate types.

Before we continue, let’s introduce an abstraction we’ll work with on and off throughout the book. Sending email is a ubiquitous requirement of most systems built today, so let’s introduce an abstraction over the functionality of sending an email, ISendEmail:

public interface ISendEmail { string GetEmailServerAddress(); bool BodyIsHtml { get; set; } } |

Code Listing 25: ISendEmail and its members

The ISendEmail interface has three members: two methods (one that returns a string, and one that returns void), and a property getter/setter.

Calling Methods

Here’s how to use A.CallTo to configure the GetEmailServerAddress method on the faked ISendEmail interface:

var emailSender = A.Fake<ISendEmail>(); A.CallTo(() => emailSender.GetEmailServerAddress()); |

Code Listing 26: Configuring a call to a method that returns a value

Note: We’re purposely not including return behavior in these code listings. We’ll be exploring return values in Chapter 6, “Configuring Calls to a Fake.”

Here’s how to use A.CallTo to configure the SendMail method on the faked ISendEmail interface:

var emailSender = A.Fake<ISendEmail>(); A.CallTo(() => emailSender.SendMail()); |

Code Listing 27: Configuring a call to a method that does not return a value

Note here that the configuration is the same for both methods, but if you press F12 into the CallTo definition for each configured method, you’ll see a difference.

When we’re setting up a call to SendMail, you’re providing an Expression<Action> to A.CallTo, and when you’re setting up a call to GetEmailServerAddress, you’re providing an Expression<Func<T>> to A.CallTo.

Note: This is because SendMail does not return a value, and GetEmailServerAddress does, which is the difference between the Action<T> and Func<T> delegate types in the .NET framework. More on the difference between Action<T> and Func<T> can be found here: http://stackoverflow.com/questions/4317479/func-vs-action-vs-predicate.

Calling Properties

Here’s how to use A.CallTo to configure the BodyIsHtml property on the faked ISendEmail interface:

var emailSender = A.Fake<ISendEmail>(); A.CallTo(() => emailSender.BodyIsHtml); |

Code Listing 28: Configuring a call to a property

Note: It is possible to call into protected members as well. We’ll be going over how to do just that in Chapter 9, “Faking the Sut.”

A Closer Look at A.CallTo

Let’s dig even deeper and take a look at the IntelliSense we’ll see when configuring calls on the faked ISendEmail interface.

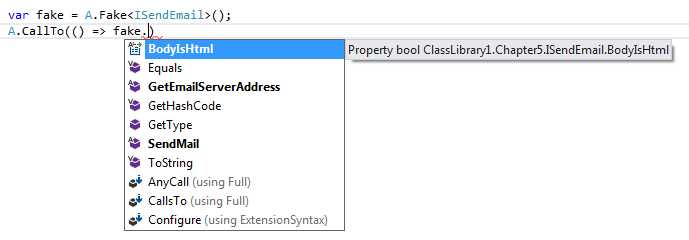

After creating the fake, this is what we’ll see available from the fake when starting to type A.CallTo:

Figure 18: Members available from the fake

We’ll look at BodyIsHtml, GetEmailServerAddress and SendMail methods one at a time and see what IntelliSense is available to us.

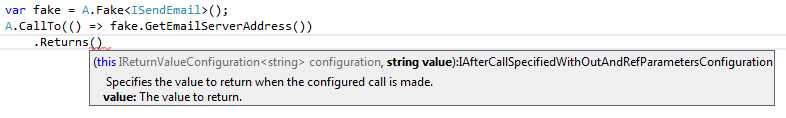

Configuring GetEmailServerAddress

When we type GetEmailServerAddress from out created fake, we’re not prompted to provide any arguments, because the method does not take any. When we close off the final parenthesis of A.CallTo, you’ll see a list of other available FakeItEasy calls. For now, pick Returns. When we pick Returns, we can see in the IntelliSense that FakeItEasy already knows what type that GetEmailServerAddress returns and prompts us for a value.

Figure 19: Configuring GetEmailServerAddress

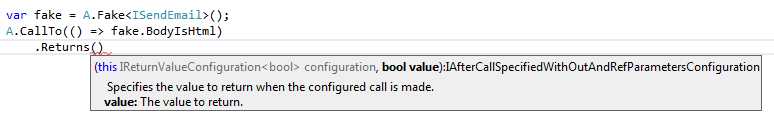

Configuring BodyIsHtml

For configuring BodyIsHtml, the IntelliSense looks the same.

Figure 20: Configuring BodyIsHtml

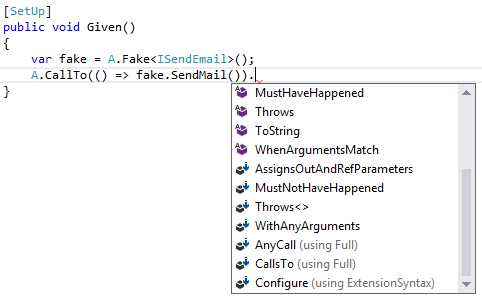

Configuring SendMail

When we configure SendEmail, things look different:

Figure 21: Configuring SendMail

Note the lack of the Returns call here. FakeItEasy is smart enough to know not to show Returns in the available choices because SendMail does not return anything.

How does FakeItEasy do this? If you look again at CallTo, you’ll see that two of the three overloads take an Expression. FakeItEasy uses this Expression to power the API choices it exposes to you in IntelliSense in your IDE based on the created fake.

Tip: A great introductory resource for learning about Expression Trees is Scott Allen’s PluralSite tutorial (http://www.pluralsight.com/courses/linq-fundamentals) on LINQ Fundamentals.

Thankfully, FakeItEasy did all the heavy lifting and wrote the code that is responsible for parsing the expression to give us, the consumer, a fluent API with which to work. All we need to do is to specify the fake, and then, using FakeItEasy’s guidance, configure it.

Summary

In this section, we’ve learned about how to configure a fake, explored A.CallTo’s overloads, and showed some configurations for different types of members on fake.

In order for the fake to be useful, we want control something about it. We now know how to configure a fake, but we really can’t do much with the configured fake yet—and that’s where the true power of FakeItEasy lies. We’ll learn how to do this in the next chapter, “Specifying a Fake’s Behavior.”

- 1800+ high-performance UI components.

- Includes popular controls such as Grid, Chart, Scheduler, and more.

- 24x5 unlimited support by developers.