CHAPTER 8

Arguments

So far we’ve seen how to create a fake, how to configure it, how to specify behavior, and how to use FakeItEasy for assertions. Through all the samples so far, we’ve been using an ISendEmail interface that exposes members with no arguments.

public interface ISendEmail { void SendMail(); } |

Code Listing 79: The ISendEmail interface

In the real world, calling a SendMail method that takes no arguments is really not that useful. We know we want to send email, but to send email, you need information like a “from” address, a “to” address, and subject and body, at the minimum.

In this chapter, we’ll be exploring how to pass and constrain arguments to faked members, as well as looking how these constraints can be used in our assertions on our fakes.

Passing Arguments to Methods

Let’s start by adding some arguments to our SendMail member on our ISendEmail interface:

public interface ISendEmail { void SendMail(string from, string to, string subject, string body); } |

Code Listing 80: The new ISendEmail interface that takes arguments

Let’s also add an Email member to our Customer class:

public class Customer { public string Email { get; set; } } |

Code Listing 81: The Customer class with an Email property

Returning to our previous examples of a CustomerService class, let’s take a look at how the changed ISendEmail interface and Customer class look when being used in code:

public class CustomerService { private readonly ISendEmail emailSender; private readonly ICustomerRepository customerRepository; public CustomerService(ISendEmail emailSender, ICustomerRepository customerRepository) { this.emailSender = emailSender; this.customerRepository = customerRepository; } public void SendEmailToAllCustomers() { var customers = customerRepository.GetAllCustomers(); foreach (var customer in customers) { emailSender.SendMail("[email protected]", customer.Email, "subject", "body"); } } } |

Code Listing 82: The CustomerService class

When we begin looping through our returned customers, for each customer, we’re passing arguments to SendMail. Three arguments are hard-coded, and one is using the Email member on the Customer class.

Let’s write a unit test that asserts that SendMail is invoked for each customer returned from ICustomerRepository.

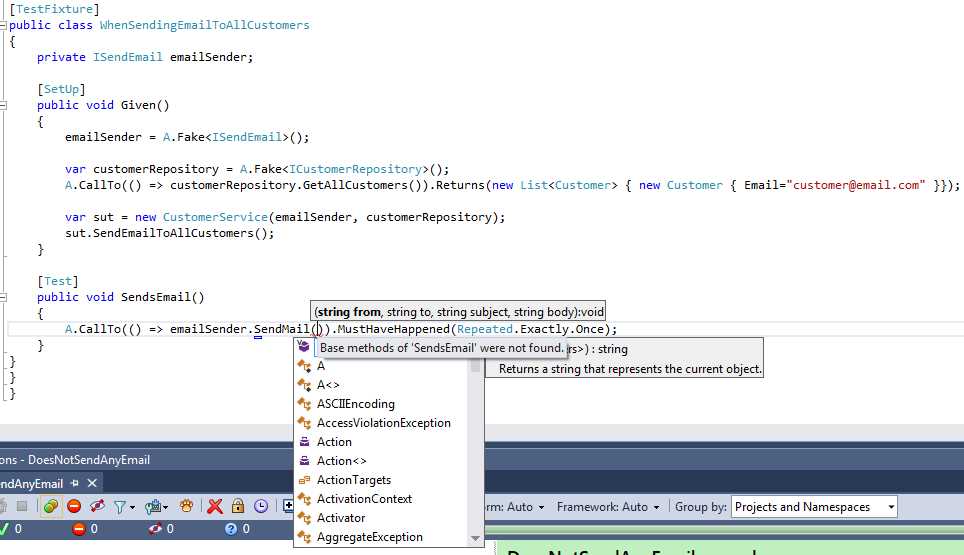

Figure 27: Asserting a call to SendMail happens when using SendMail with arguments

As you can see from Figure 27, when we go to write our assertion against SendMail, we’re prompted for the arguments that SendMail requires. What do we put here? For now, since we’re just trying to assert that the call happened a specified number of times, let’s put in string.Empty for each argument.

[TestFixture] public class WhenSendingEmailToAllCustomers { private ISendEmail emailSender; [SetUp] public void Given() { emailSender = A.Fake<ISendEmail>(); var customerRepository = A.Fake<ICustomerRepository>(); A.CallTo(() => customerRepository.GetAllCustomers()).Returns( new List<Customer> { new Customer { Email="[email protected]" }}); var sut = new CustomerService(emailSender, customerRepository); sut.SendEmailToAllCustomers(); } [Test] public void SendsEmail() { A.CallTo(() => emailSender .SendMail(string.Empty, string.Empty, string.Empty, string.Empty)) .MustHaveHappened(Repeated.Exactly.Once); } } |

Code Listing 83: Passing string.Empty in for each argument to SendMail

Now we have a compiling test. But when we go to run this test, it fails:

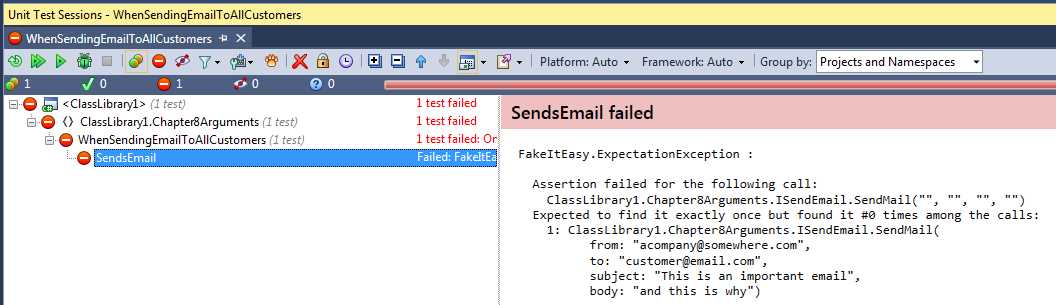

Figure 28: SendsEmail failed

Why? FakeItEasy is now expecting certain values for each call to SendMail. In our assertion, we’re passing all string.Empty values, which allows the test to compile, but fails when we run it because SendMail is being invoked with arguments that are not equal to all string.Empty values.

Knowing this information, let’s re-write the test method to pass in the correct arguments:

[TestFixture] public class WhenSendingEmailToAllCustomers { private ISendEmail emailSender; private Customer customer; [SetUp] public void Given() { emailSender = A.Fake<ISendEmail>(); customer = new Customer { Email = "[email protected]" }; var customerRepository = A.Fake<ICustomerRepository>(); A.CallTo(() => customerRepository.GetAllCustomers()) .Returns(new List<Customer> { customer }); var sut = new CustomerService(emailSender, customerRepository); sut.SendEmailToAllCustomers(); } [Test] public void SendsEmail() { A.CallTo(() => emailSender .SendMail("[email protected]", customer.Email, "subject", "body")) .MustHaveHappened(Repeated.Exactly.Once); } } |

Code Listing 84: Correcting the arguments for the SendMail call

When we run this test, it passes. Note how we took the three hard-coded values from the CustomerService class in combination with the customer’s email address and used those values in our assertion in the SendsEmail test method. Now we’re asserting against the correct argument values as well as the number of calls to the SendMail method.

A<T>.Ignored

In Code Listing 83, we initially tried to pass four string.Empty values to our SendMail method in our assertion code, and quickly learned we could not do that. We needed to pass the correct values for our test to pass.

But sometimes, you don’t care about the values of arguments passed to a fake. A good example of this would be a scenario we already covered earlier in the book in Chapter 7 on Assertions, where we were asserting that a call to SendMail did NOT happen using MustNotHaveHappened. This is where A<T>.Ignored comes in handy.

Let’s return to that example, asserting SendMail was not called in order to demonstrate how to use A<T>.Ignored. In this case, our CustomerService class does not change from Code Listing 78, but our unit test will.

Here is the unit test for testing that a call to SendEmail did not happen using A<T>.Ignored:

[TestFixture] { private ISendEmail emailSender; [SetUp] public void Given() { emailSender = A.Fake<ISendEmail>(); var sut = new CustomerService(emailSender, A.Fake<ICustomerRepository>()); sut.SendEmailToAllCustomers(); } [Test] public void DoesNotSendEmail() { A.CallTo(() => emailSender.SendMail(A<string>.Ignored, A<string>.Ignored, A<string>.Ignored, A<string>.Ignored)).MustNotHaveHappened(); } } |

Code Listing 85: Using A<T>.Ignored to assert that a call to SendMail did not happen

Since the compiler forces us to provide values to SendMail, but we don’t really care about the values for testing since SendMail was not called in this unit test, we use A<T>.Ignored by passing it a string type for T for each argument. A<T>.Ignored works with all types, not just primitive types.

Note: Although we could still pass in string.Empty for each argument to SendMail in this test case, and our test will still pass, by using A<T>.Ignored, you’re being explicit about the intent of the unit test. Our intent here is to show whoever is reading the code that we truly don’t care about the values being passed to SendMail for this test. If we were to use string.Empty in place of A<T>.Ignored, are we expecting empty strings for the unit test to pass, or do we not care about the values of the arguments? This is an important differentiation to make. A<T>.Ignored clears up that question for us.

Tip: you can use A<T>._ as shorthand for A<T>.Ignored

A.Dummy<T>

A.Dummy<T> is very similar to A<T>.Ignored. So what’s the difference? A<T>.Ignored should be used for configuration and assertions for methods on fakes. A.Dummy<T> can be used to pass in default values for T to a method on a class that has been instantiated using the new keyword. A.Dummy<T> cannot be used to configure calls. Let’s look at a quick example.

We’ll again use sending email as an example. Here is the ISendEmail interface for this example:

public interface ISendEmail { Result SendEmail(string from, string to); } |

Code Listing 86: The ISendEmail interface

You can see that we’re returning a Result object from the SendEmail method call. This Result object will contain a list of potential error messages. This is what the Result class looks like:

public class Result { public Result() { this.ErrorMessages = new List<string>(); }

public List<string> ErrorMessages; } |

Code Listing 87: The Result class

In the constructor, we are newing up the list so the consuming code doesn’t have to deal with null reference exceptions when there are no errors.

Next, our SUT, the CustomerService class:

public class CustomerService { private readonly ISendEmail emailSender; public CustomerService(ISendEmail emailSender) { this.emailSender = emailSender; } public Result SendEmail(string from, string to) { var result = new Result(); if (string.IsNullOrEmpty(to)) { result.ErrorMessages.Add("Cannot send an email with an empty to address"); return result; }

emailSender.SendEmail(from, to);

return result; } } |

Code Listing 88: The CustomerService class

In the SendEmail method, you can see that we’re doing a string.IsNullOrEmpty check on the to argument passed into the method. If it’s null or empty, we add a message to the ErrorMessages list on Result, and return the result without invoking emailSender.SendMail. If the to argument passes the string.IsNullOrEmpty check, then we invoke the emailSender’s SendMail method and return the result with an empty list.

We’re going to write a unit test that tests a scenario when the to argument is NullOrEmpty. Here is the CustomerServiceTests use of A.Dummy<T>.

[TestFixture] public class WhenSendingAnEmailWithAnEmptyToAddress { private Result result; [SetUp] public void Given() { var sut = new CustomerService(A.Fake<ISendEmail>()); result = sut.SendEmail(A.Dummy<string>(), ""); } [Test] public void ReturnsErrorMessage() { Assert.That(result.ErrorMessages.Single(), Is.EqualTo("Cannot send an email with an empty to address")); } } |

Code Listing 89: CustomerServiceTests using A.Dummy<T>

In this test, you’ll see we’re passing in A.Dummy<string> for the from argument. Because our execution path for this test does not rely on this from argument value at all, we’re using A.Dummy<string> to represent the from argument.

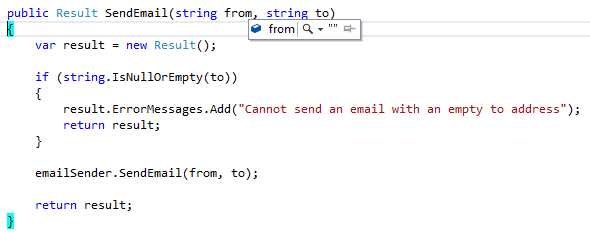

If you set a breakpoint on result = sut.SendEmail(A.Dummy<string>(), "");, debug this unit test and step into SendEmail, you’ll see A.Dummy<T> passes the string default to SendEmail for the from argument:

Figure 29: Using A.Dummy<T> results in the default for T being passed into the method. In this case, it’s an empty string

The decision to use A.Dummy<T> here instead of passing in a string.Empty value in this unit test is similar to the decision to use A<string>.Ignored in the assertion in Code Listing 85; using A.Dummy<T> communicates intent better.

When you see A.Dummy<T> being used, it’s a sign that the value for a given argument is not important for the particular test you’re writing. This most likely means the value will not be used in the execution path in the SUT’s method as we see in our SendEmail method on CustomerService.

Again, you could pass string.Empty for the from argument and the test would still pass. But does that mean the test needs a string.Empty value for the from argument for the test to pass? Does that mean the from argument’s value will be used in the execution path for the test? Without looking at the SUT’s code, the test setup using FakeItEasy does not easily answer that question. Using A.Dummy<T> explicitly says to the person looking at your code, “this value is not used in the execution path, so we don’t care about it.”

Don’t keep other programmers guessing about your intent. Make it clear with A.Dummy<T>

Constraining Arguments

We’ve already been constraining arguments in the previous section on Passing Arguments to Methods. That in itself was a way to constrain arguments and then assert that the fake’s member was called with the correct values.

We’re going to take the next step in constraining arguments by examining the very powerful That.Matches operator.

That.Matches

Testing a method that takes primitive types when asserting that something must have happened is fairly straightforward—but we’re not always so lucky to deal with primitive types when we’re working with methods on fakes.

FakeItEasy provides a way to constrain arguments that are passed to methods on fakes. To demonstrate this functionality, it’s time to change ISendEmail again. Instead of taking four strings, SendMail will now take an Email object.

public interface ISendEmail { void SendMail(Email email); } |

Code Listing 90: New ISendMail method signature, introduction of Email class

public class Email { public string From { get; set; } public string To { get; set; } public string Subject { get; set; } public string Body { get; set; } } |

Code Listing 91: Email class

All we’ve really done here is encapsulate the four string vales that used to be passed to SendMail into an Email class.

Here is the how the change impacts our CustomerService class:

public class CustomerService { private readonly ISendEmail emailSender; private readonly ICustomerRepository customerRepository; public CustomerService(ISendEmail emailSender, ICustomerRepository customerRepository) { this.emailSender = emailSender; this.customerRepository = customerRepository; } public void SendEmailToAllCustomers() { var customers = customerRepository.GetAllCustomers(); foreach (var customer in customers) { emailSender.SendMail( new Email { From = "[email protected]", To = customer.Email, Subject = "subject", Body = "body" }); } } } |

Code Listing 92: Creating a new Email object and passing in the four values as parameters

Note how we’re “newing up” an Email object and populating the values with the same values that used to be passed to the SendMail method when it took four strings.

We want to assert that SendMail was called with the correct customer’s email address. This is how we write a unit test for that scenario using That.Matches:

[TestFixture] public class WhenSendingEmailToAllCustomers { private ISendEmail emailSender; private const string customersEmail = "[email protected]"; [SetUp] public void Given() { emailSender = A.Fake<ISendEmail>(); var customerRepository = A.Fake<ICustomerRepository>(); A.CallTo(() => customerRepository.GetAllCustomers()) .Returns(new List<Customer> { new Customer { Email = customersEmail }});

var sut = new CustomerService(emailSender, customerRepository); sut.SendEmailToAllCustomers(); } [Test] public void SendsEmail() { A.CallTo(() => emailSender.SendMail( A<Email>.That.Matches(email => email.To == customersEmail))) .MustHaveHappened(Repeated.Exactly.Once); } } |

Code Listing 93: Using .That.Matches to test the CustomerService class

In our earlier example, we used real strings to test the happy path of SendMail, and A<string>.Ignored to test the non-happy path. Now that SendMail takes an Email object, you can see how we’re using That.Matches to test the correct values were used on Email when making the SendMail call.

A<Email>.That.Matches(email => email.To == customersEmail)

That.Matches takes an Expression<Func<T, bool>>, where T is the type specified in A<T>. In this example, T is Email.

Note: I did not assert that the other properties of Email were correct in the preceding unit test like I did for earlier unit tests. I left them out to make the code sample easier to read, not because they’re not important.

Using That.Matches in a FakeItEasy call is called custom matching. This means we need to write our own matcher. Let’s explore a couple other pre-written matchers that can provide some common matching scenarios, instead of having to use That.Matches.

That.IsInstanceOf(T)

That.IsInstanceOf can be used for testing a specific type is being passed to a SUT’s method. This comes in really handy when you’re working with a SUT’s method that takes an object or an interface as its type. This method might be given multiple object types within the context of a single test on a SUT’s method.

Let’s explore the simpler of the two examples: a SUT’s method that takes an object as an argument. Since I work with a messaging bus called NServiceBus every day, for this example, we’ll introduce a new abstraction called IBus:

public interface IBus { void Send(object message); } |

Code Listing 94: The IBus interface

Think of the IBus interface as an abstraction over a service bus that is responsible for sending “messages” within a system. This IBus interface allows us to send any type of object.

Now that we have our abstraction set up, here is the “message” we’ll be sending:

public class CreateCustomer { public string FirstName { get; set; } public string LastName { get; set; } public string Email { get; set; } } |

Code Listing 95: The CreateCustomer message

Think of the message as a simple DTO (http://martinfowler.com/eaaCatalog/dataTransferObject.html) that contains data about the customer we want to create.

Here is the implementation using IBus and CreateCustomer in a class called CustomerService:

public class CustomerService { private readonly IBus bus; public CustomerService(IBus bus) { this.bus = bus; } public void CreateCustomer(string firstName, string lastName, string email) { bus.Send(new CreateCustomer { FirstName = firstName, LastName = lastName, Email = email }); } } |

Code Listing 96: The CustomerService class

The CreateCustomer method takes three strings about the customer we want to create and uses that information to populate the CreateCustomer message. That message is then passed to the Send method on IBus. In a service-bus based architecture, this “message” would have a corresponding handler somewhere that handles the CreateCustomer message and does something with it (for example, writing a new customer to the database).

Here is the unit test:

[TestFixture] public class WhenCreatingACustomer { private IBus bus; [SetUp] public void Given() { bus = A.Fake<IBus>(); var sut = new CustomerService(bus); sut.CreateCustomer("FirstName", "LastName", "Email"); } [Test] public void SendsCreateCustomer() { A.CallTo(() => bus.Send( A<object>.That.IsInstanceOf(typeof(CreateCustomer)))) .MustHaveHappened(Repeated.Exactly.Once); } } |

Code Listing 97: Unit test for the CreateCustomer class

What we need to test here is that the type passed to bus.Send is a type of CreateCustomer and that the call happened. We do this by using IsInstanceOf in our assertion.

Although we’ve successfully tested for the correct message type our unit test, this test is not complete yet. We still would need to test that the values we’re passing to the SUT’s CreateCustomer method end up on the CreateCustomer message.

For more information on how assert each individual property of an object instance is equal to input provided in the test setup, see the “Dealing With Object” section in this chapter.

That.IsSameSequenceAs<T>

Sometimes we want to assert that a sequence is the same when passing a collection to a fake’s method. This especially useful when working with common collection types in .NET like IEnumerable<T> and List<T>. This is where IsSameSequenceAs<T> comes in handy.

I’m going to reintroduce the example code from Chapter 6 that showcased Invokes using the IBuildCsv interface.

As a reminder, here are the classes and interfaces we dealt with earlier:

public interface IBuildCsv { void SetHeader(IEnumerable<string> fields); void AddRow(IEnumerable<string> fields); string Build(); } |

Code Listing 98: The IBuildCsv abstraction

public class Customer { public string LastName { get; set; } public string FirstName { get; set; } } |

Code Listing 99: The Customer class

public class CustomerService { private readonly IBuildCsv buildCsv; public CustomerService(IBuildCsv buildCsv) { this.buildCsv = buildCsv; } public string GetLastAndFirstNamesAsCsv(List<Customer> customers) { buildCsv.SetHeader(new[] { "Last Name", "First Name" }); customers.ForEach(customer => buildCsv.AddRow(new [] { customer.LastName, customer.FirstName })); return buildCsv.Build(); } } |

Code Listing 100: The CustomerService class

Our goal here is the same as it was when we were working with Invokes. We want to make sure the correct header is built and then the correct values are added to each “row” in the CSV based on the customer list passed into the SUT’s method.

Let’s start by taking a look at the test setup for CustomerService:

[TestFixture] public class WhenGettingCustomersLastAndFirstNamesAsCsv { private IBuildCsv buildCsv; private List<Customer> customers; [SetUp] public void Given() { buildCsv = A.Fake<IBuildCsv>(); var sut = new CustomerService(buildCsv); customers = new List<Customer> { new Customer { LastName = "Doe", FirstName = "Jon"}, new Customer { LastName = "McCarthy", FirstName = "Michael" } };

sut.GetLastAndFirstNamesAsCsv(customers); } |

Code Listing 101: Unit test setup for testing CustomerService class

Here we’re creating our fake, creating our SUT, and then setting up a list of customers to use. We then pass the list of customers to GetLastAndFirstNamesAsCsv on the SUT. Note that we’re not defining behavior of our fake in the test setup. We’re just creating it and passing it to the constructor of the SUT. For this example, we’ll be using our fake in assertions only.

Next, let’s explore four tests in the test class based on the setup we’ve done so far.

[Test] public void SetsCorrectHeader() { A.CallTo(() => buildCsv.SetHeader(A<IEnumerable<string>> .That.IsSameSequenceAs(new[] { "Last Name", "First Name"}))) .MustHaveHappened(Repeated.Exactly.Once); } [Test] public void AddsCorrectRows() { A.CallTo(() => buildCsv.AddRow(A<IEnumerable<string>>.That.IsSameSequenceAs (new[] { customers[0].LastName, customers[0].FirstName }))) .MustHaveHappened(Repeated.Exactly.Once); A.CallTo(() => buildCsv.AddRow(A<IEnumerable<string>>.That.IsSameSequenceAs( new[] { customers[1].LastName, customers[1].FirstName}))) .MustHaveHappened(Repeated.Exactly.Once); } [Test] public void AddRowsIsCalledForEachCustomer() { A.CallTo(() => buildCsv.AddRow(A<IEnumerable<string>>.Ignored)) .MustHaveHappened(Repeated.Exactly.Times(customers.Count)); } [Test] public void CsvIsBuilt() { A.CallTo(() => buildCsv.Build()).MustHaveHappened(Repeated.Exactly.Once); } |

Code Listing 102: The test methods for CustomerService

- SetsCorrectHeader: In this test, we use That.IsSameSequenceAs to base the assertion against the hard-coded IEnumerable<string> that is also present in the GetLastAndFirstNamesAsCsv method of the SUT. In this case, using the hard-coded values in our unit test is acceptable because the method we’re testing on the SUT is also working with a hard-coded IEnumerable<string>.

- AddsCorrectRows: We use the same approach that we used for SetsCorrectHeader, except in this case, we have to assert that the AddRow method was called with the appropriate customer last name and first name values for each customer in the list by using That.IsSameSequenceAs. In order to do this, we use the data we set up in the customers variable and then access that data via index in the test. There is a better way to write this particular unit test that we’ll look at after the rest of the test methods overview.

- AddRowsIsCalledForEachCustomer: This test method does not use That.IsSameSequenceAs, but I wanted to include it because nowhere are we asserting that the AddRow method on our fake is being called for the number of customers we’ve passed to GetLastAndFirstNamesAsCsv. This test takes care of covering that assertion.

- CsvIsBuilt: In order to get the CSV string back, we need to assert that this method was called. If not, all we’ll be returning from GetLastAndFirstNamesAsCsv is an empty string.

As promised earlier, let’s revisit the AddsCorrectRows unit test. I mentioned, there is a better way to write this. Based on the test setup and the assertions that need to be made, there is a way to let the test setup (input) to the SUT drive the assertion. Take a second to look at both the test setup and the unit tests and see if you can figure it out.

Since we’re currently using customers.Count as part of our assertion in the AddRowsIsCalledForEachCustomer test method, we can use this same list of customers to assert that AddRow was called for each customer in that list. Here is the updated AddsCorrectRows unit test:

[Test] public void AddsCorrectRows() { foreach (var customer in customers) { A.CallTo(() => buildCsv.AddRow(A<IEnumerable<string>>.That.IsSameSequenceAs (new[] { customer.LastName, customer.FirstName }))) .MustHaveHappened(Repeated.Exactly.Once); } } |

Code Listing 103: The improved AddsCorrectRows unit test

Here we let the customer list drive the assertion against each AddRow call. This eliminates the multiple line call we had earlier, in which we used a hard-coded index against the customer list. By making this change, we’ve allowed our test input to drive the assertions 100 percent, as well as improved the accuracy and maintainability of our tests.

Dealing with Object

So far, we’ve been constraining arguments that have all been defined as custom types or primitives. We’ve examined different methods available to us via the That keyword. But what happens when we’re dealing with constraining arguments on a class and one of the class’s members is of type object?

Continuing with our customer example, we’re going to change things around a bit and introduce the concept of sending an email for “preferred” customers instead of all customers. We’ll add a class that represents the preferred customer email, and we’ll assign that to a property that is of type object on an Email class.

Note: The code I’m about to present is only for the sake of this example. There are better ways to implement what I’m about to write, but if you’re like most programmers, you’re working in a codebase where change might be very difficult, or in some cases, impossible, which means you could potentially have to write unit tests against an existing codebase you have very little control over. So please keep in mind the code that appears next is not a recommended way to implement this particular piece of functionality.

The PreferredCustomerEmail class:

public class PreferredCustomerEmail { public string Email { get; set; } } |

Code Listing 104: The PreferredCustomerEmail class

The Email class:

public class Email { public object EmailType { get; set; } } |

Code Listing 105: The Email class

Note the EmailType property on the Email class.

The intention with the Email class is to assign a PreferredCustomerEmail class instance to the EmailType property. For example, there might be a regular CustomerEmail class that also could be assigned to this property. Obviously, all this could be accomplished much more nicely by using inheritance, but for the sake of the example, let’s continue to move forward with this code.

Let’s tie it all together with the CustomerService class:

public class CustomerService { private readonly ISendEmail emailSender; private readonly ICustomerRepository customerRepository; public CustomerService(ISendEmail emailSender, ICustomerRepository customerRepository) { this.emailSender = emailSender; this.customerRepository = customerRepository; } public void SendEmailToPreferredCustomers() { var customers = customerRepository.GetAllCustomers(); foreach (var customer in customers) if (customer.IsPreferred) emailSender.SendMail(new Email { EmailType = new PreferredCustomerEmail { Email = customer.Email }}); } } |

Code Listing 106: The CustomerService class

First, you can see that we’re filtering the customers by this conditional statement:

if (customer.IsPreferred). We’re only calling SendMail for that those customers.

Next, you can see that we’re newing up a PreferredCustomerEmail in the SendEmailToPreferredCustomers method, and then assigning that instance into the EmailType property of a newed up Email instance.

So far, this might not look very different from other tests we’ve written in the book, but let’s write a unit test for this method. What I’m trying to assert is that the email is sent to the correct email address.

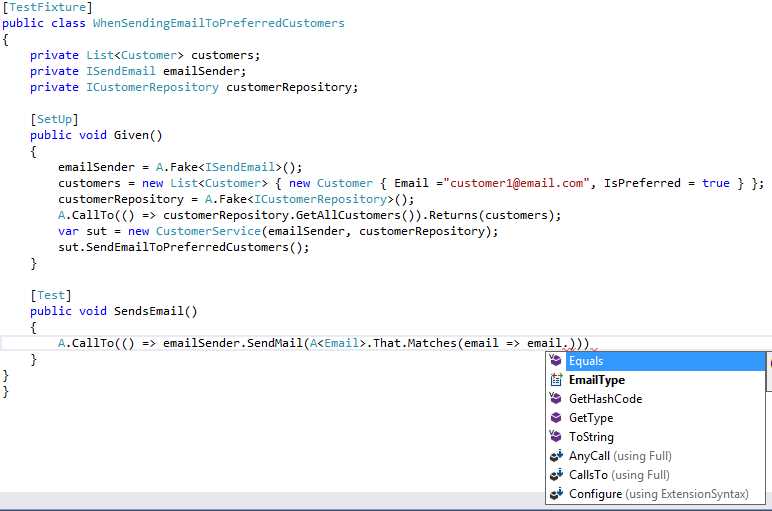

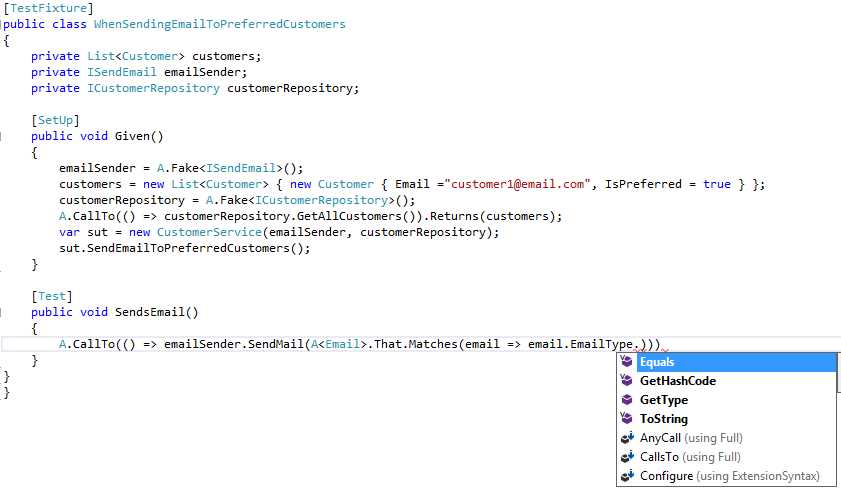

Here is a screen grab of the IntelliSense in my IDE:

Figure 30: Trying to get the email address to assert against in the unit test

In earlier examples, when we were trying to assert that the email was sent to the correct email address, our Email class contained a string property called Email, and we could assert against that value easily. But now that our Email class takes an object property called EmailType, how do we get at the actual email address we want to assert against?

Let’s choose EmailType, and see what IntelliSense gives us:

Figure 31: We still can’t get to the email value we want to assert against

Here you’ll see that we still cannot get to the email value we want to assert against. The only things for us to pick are the IntelliSense items offered to us by an object type.

How are we going to test this class? We need a way to cast EmailType to the correct class in order to get access to that classes Email property.

Here is the unit test that will make it possible:

[TestFixture] public class WhenSendingEmailToPreferredCustomers { private List<Customer> customers; private ISendEmail emailSender; private ICustomerRepository customerRepository; [SetUp] public void Given() { emailSender = A.Fake<ISendEmail>(); customers = new List<Customer> { new Customer { Email ="[email protected]", IsPreferred = true } }; customerRepository = A.Fake<ICustomerRepository>(); A.CallTo(() => customerRepository.GetAllCustomers()).Returns(customers); var sut = new CustomerService(emailSender, customerRepository); sut.SendEmailToPreferredCustomers(); } [Test] public void SendsEmail() { A.CallTo(() => emailSender.SendMail(A<Email>.That.Matches( x => (x.EmailType as PreferredCustomerEmail).Email == customers[0].Email))) .MustHaveHappened(Repeated.Exactly.Once); } } |

Code Listing 107: Casting the object property type to the correct class to get the email value

Here you can see that we’re still using A<Email>.That.Matches, but in our lambda, instead of x => x.Email, we’re using x => (x.EmailType as PreferredCustomerEmail).

By casting the object to the type we need in Matches, we can then finally access the Email property that contains the email address we wish to assert against.

Extra Credit: Write a unit test that will test the non-happy path of the implementation currently in the CustomerService class. You can see the conditional check in there, and that’s almost always a sign that multiple tests should be written.

Other Available Matchers

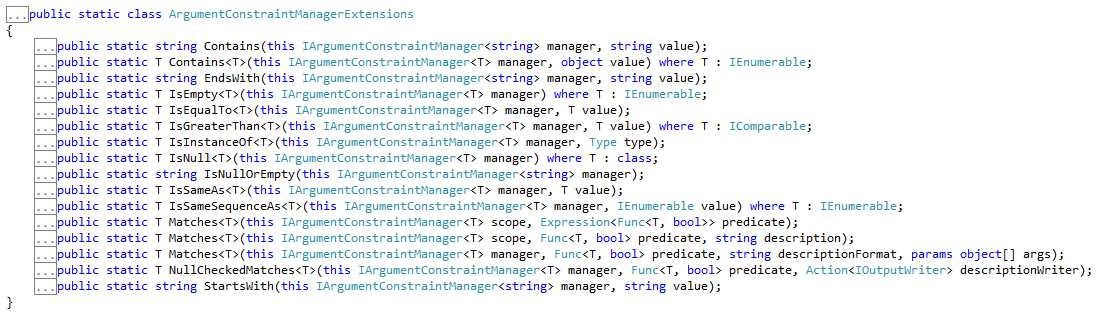

FakeItEasy provides us with other built-in matchers besides the ones we’ve been exploring in this chapter, via That. In our IDE, if we hit F12, and file over the Matches function, we’ll be brought to the ArgumentConstraintManagerExtensions static class:

Figure 32: The ArgumentConstraintManagerExtensions class

You are encouraged to explore and experiment with all the matchers provided by this static class. A full list of available matchers can be found here: https://github.com/FakeItEasy/FakeItEasy/wiki/Argument-Constraints.

Summary

Argument matchers are very powerful, whether using the ones FakeItEasy provides, or writing your own custom matcher(s). I recommend you spend some time working with all of the FakeItEasy-supplied matchers as well as trying to build your own. In this chapter, we learned how to pass arguments to methods, how to use FakeItEasy-provided matchers, how to write custom matchers, and how to deal with object.

At this point, we’ve covered all the basics of what you need to get up and running with FakeItEasy in your unit tests. This should be able to cover 75 percent or more of your faking and unit testing needs. All of the examples we’ve been using and exploring up until this point have been focusing on faking interfaces that have been injected into classes (our SUT), and then specifying setup and behavior for those faked interfaces.

What we have NOT seen yet is if we need to fake the SUT itself. In the next chapter, we’ll work through an entire example of why we would want to fake the SUT, how to fake the SUT, and explore how it differs from using FakeItEasy to configure injected dependencies.

- 1800+ high-performance UI components.

- Includes popular controls such as Grid, Chart, Scheduler, and more.

- 24x5 unlimited support by developers.