CHAPTER 11

Performance Optimizations

Filter Entities in the Database

You are certainly aware that Entity Framework works with two flavors of LINQ:

- LINQ to Objects: operations are performed in memory.

- LINQ to Entities: operations are performed in the database.

LINQ to Entities queries that return collections are executed immediately after calling a “terminal” method—one of ToList, ToArray, or ToDictionary. After that, the results are materialized and are therefore stored in the process’ memory space. Being instances of IEnumerable<T>, they can be manipulated with LINQ to Objects standard operators without us even noticing. What this means is, it is totally different to issue these two queries, because one will be executed fully by the database, while the other will be executed by the current process.

//LINQ to Objects: all Technologies are retrieved from the database and filtered in memory var technologies = ctx.Technologies.ToList().Where(x => x.Resources.Any()); //LINQ to Entities: Technologies are filtered in the database, and only after retrieved into memory var technologies = ctx.Technologies.Where(x => x.Resources.Any()).ToList(); |

Beware, you may be bringing a lot more records than what you expected!

Do Not Track Entities Not Meant for Change

Entity Framework has a first level (or local) cache where all the entities known by an EF context, loaded from queries or explicitly added, are stored. This happens so that when time comes to save changes to the database, EF goes through this cache and checks which ones need to be saved, meaning which ones need to be inserted, updated, or deleted. What happens if you load a number of entities from queries when EF has to save? It needs to go through all of them, to see which have changed, and that constitutes the memory increase.

If you don’t need to keep track of the entities that result from a query, since they are for displaying only, you should apply the AsNoTracking extension method.

//no caching var technologies = ctx.Technologies.AsNoTracking().ToList(); var technologiesWithResources = ctx.Technologies.Where(x => x.Resources.Any()) .AsNoTracking().ToList(); var localTechnologies = ctx.Technologies.Local.Any(); //false |

This even causes the query execution to run faster, because EF doesn’t have to store each resulting entity in the cache.

Disable Automatic Detection of Changes

Another optimization is related to the way Entity Framework runs the change tracking algorithm. By default, the DetectChanges method is called automatically in a number of occasions, such as when an entity is explicitly added to the context, when a query is run, etc. This results in degrading performance whenever a big number of entities is being tracked.

The workaround is to disable the automatic change tracking by setting the AutoDetectChangesEnabled property appropriately.

//disable automatic change tracking ctx.Configuration.AutoDetectChangesEnabled = false; |

Do not be alarmed: whenever SaveChanges is called, it will then call DetectChanges and everything will work fine. It is safe to disable this.

Use Lazy, Explicit, or Eager Loading Where Appropriate

As you saw on section Lazy, Explicit, and Eager Loading, you have a number of options when it comes to loading navigation properties. Generally speaking, when you are certain of the need to access a reference property or go through all of the child entities present in a collection, you should eager load them with their containing entity. There’s a known problem called SELECT N + 1 which illustrates just that: you issue one base query that returns N elements and then you issue another N queries, one for each reference/collection that you want to access.

Performing eager loading is achieved by applying the Include extension method.

//eager load the Technologies for each Resource

var resourcesIncludingTechnologies = ctx.Resources.Include(x => x.Technologies) .ToList();

//eager load the Customer for each Project var projectsIncludingCustomers = ctx.Projects.Include("Customer").ToList(); |

This way you can potentially save a lot of queries, but it can also bring much more data than the one you need.

Use Projections

As you know, normally the LINQ and Entity SQL queries return full entities; that is, for each entities, they bring along all of its mapped properties (except references and collections). Sometimes we don’t need the full entity, but just some parts of it, or even something calculated from some parts of the entity. For that purpose, we use projections.

Projections allow us to reduce significantly the data returned by hand picking just what we need. Here are some examples in both LINQ and Entity SQL.

//return the resources and project names only with LINQ var resourcesXprojects = ctx.Projects.SelectMany(x => x.ProjectResources) .Select(x => new { Resource = x.Resource.Name, Project = x.Project.Name }).ToList(); //return the customer names and their project counts with LINQ var customersAndProjectCount = ctx.Customers .Select(x => new { x.Name, Count = x.Projects.Count() }).ToList(); //return the project name and its duration with ESQL var projectNameAndDuration = octx.CreateQuery<Object>("SELECT p.Name, DIFFDAYS(p.Start, p.[End]) FROM Projects AS p WHERE p.[End] IS NOT NULL").ToList(); //return the customer name and a conditional column with ESQL var customersAndProjectRange = octx.CreateQuery<Object>( "SELECT p.Customer.Name, CASE WHEN COUNT(p.Name) > 10 THEN 'Lots' ELSE 'Few' END AS Amount FROM Projects AS p GROUP BY p.Customer").ToList(); |

Projections with LINQ depend on anonymous types, but you can also select the result into a .NET class for better access to its properties.

//return the customer names and their project counts into a dictionary with LINQ var customersAndProjectCountDictionary = ctx.Customers .Select(x => new { x.Name, Count = x.Projects.Count() }) .ToDictionary(x => x.Name, x => x.Count); |

Disabling Validations Upon Saving

We discussed the validation API in the Validation section. Validations are triggered for each entity when the context is about to save them, and if you have lots of them, this may take some time.

When you are 100% sure that the entities you are going to save are all valid, you can disable their validation by disabling the ValidateOnSaveEnabled property.

//disable automatic validation upon save ctx.Configuration.ValidateOnSaveEnabled = false; |

This is a global setting, so beware!

Working with Disconnected Entities

When saving an entity, if you need to store in a property a reference another entity for which you know the primary key, then instead of loading it with Entity Framework, just assign it a blank entity with only the identifier property filled.

//save a new project referencing an existing Customer var newProject = new Project { Name = "Some Project", Customer = new Customer { CustomerId = 1 } /*ctx.Customers.Find(1)*/ }; ctx.Projects.Add(newProject); ctx.SaveChanges(); |

This will work fine because Entity Framework only needs the foreign key set.

Also for deletes, no need to load the entity beforehand, its primary key will do.

//delete a Customer by id //ctx.Customers.Remove(ctx.Customers.Find(1)); ctx.Entry(new Customer { CustomerId = 1 }).State = EntityState.Deleted; ctx.SaveChanges(); |

Do Not Use IDENTITY for Batch Inserts

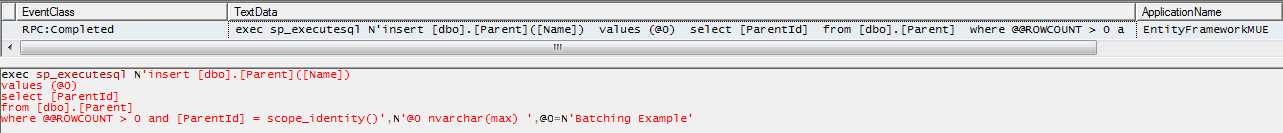

While the IDENTITY identifier generation strategy may well be the most obvious for those coming from the SQL Server world, it does have some problems when it comes to ORM; it is not appropriate for batching scenarios. Since the primary key is generated in the database and each inserted entity must be hydrated— meaning, its identifier must be set—as soon as it is persisted, SQL Server needs to issue an additional SELECT immediately after the INSERT to fetch the generated key. Let’s see an example where we use IDENTITY.

ctx.Save(new Parent { Name = "Batching Example" }); ctx.SaveChanges(); |

We can see the generated SQL in SQL Server Profiler (notice the INSERT followed by a SELECT).

Figure 58: Inserting a record and obtaining the generated key

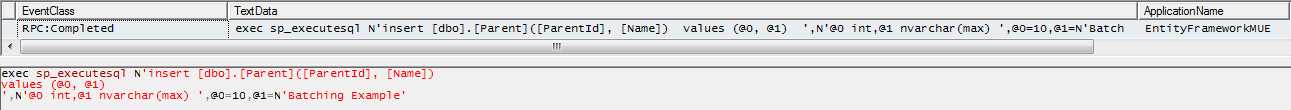

If we change the generation strategy to manual and explicitly set the primary key beforehand then we only have one INSERT.

Figure 59: Inserting a record with a manually assigned key

If you are inserting a large number of entities, this can make a tremendous difference. Of course, sometimes it may not be appropriate to use manual insertions due to concurrent accesses, but in that case it probably can be solved by using Guids as primary keys.

Note: Keep in mind that, generally speaking, ORMs are not appropriate for batch insertions.

Use SQL Where Appropriate

If you have looked at the SQL generated for some queries, and if you know your SQL, you can probably tell that it is far from optimized. That is because EF uses a generic algorithm for constructing SQL that picks up automatically the parameters from the specified query and puts it all blindly together. Of course, understanding what we want and how the database is designed, we may find a better way to achieve the same purpose.

When you are absolutely certain that you can write your SQL in a better way than what EF can, feel free to experiment with SqlQuery and compare the response times. You should repeat the tests a number of times, because other factors may affect the results, such as other accesses to the database, the Visual Studio debugger, number of processes running in the test machines, all of these can cause impact.

One thing that definitely has better performance is batch deletes or updates. Always do them with SQL instead of loading the entities, changing/deleting them one by one, and them saving the changes. Use the ExecuteSqlCommand method for that purpose.

- 1800+ high-performance UI components.

- Includes popular controls such as Grid, Chart, Scheduler, and more.

- 24x5 unlimited support by developers.