CHAPTER 4

Writing Data to the Database

Saving, updating, and deleting entities

Saving entities

Because EF works with POCOs, creating a new entity is just a matter of instantiating it with the new operator. If we want it to eventually get to the database, we need to attach it to an existing context.

Code Listing 94

var developmentTool = new DevelopmentTool() { Name = "Visual Studio 2017", Language = "C#" }; ctx.Tools.Add(developmentTool); |

New entities must be added to the DbSet<T> property of the same type, which is also your gateway for querying. Another option is to add a batch of new entities, maybe of different types, to the DbContext itself:

Code Listing 95

DevelopmentTool tool = /* something */; Project project = /* something */; Customer customer = /* something */; ctx.AddRange(tool, project, customer); |

However, this new entity is not immediately sent to the database. The EF context implements the Unit of Work pattern, a term coined by Martin Fowler, about which you can read more here. In a nutshell, this pattern states that the Unit of Work container will keep internally a list of items in need of persistence (new, modified, or deleted entities), and will save them all in an atomic manner, taking care of any eventual dependencies between them. The moment when these entities are persisted in Entity Framework Code First happens when we call the DbContext’s SaveChanges method.

Code Listing 96

var affectedRecords = ctx.SaveChanges(); |

At this moment, all the pending changes are sent to the database. Entity Framework employs a first-level (or local) cache, which is where all the “dirty” entities—like those added to the context —sit waiting for the time to persist. The SaveChanges method returns the number of records that were successfully inserted, and will throw an exception if some error occurred in the process. In that case, all changes are rolled back, and you really should take this scenario into consideration.

Updating entities

As for updates, Entity Framework tracks changes to loaded entities automatically. For each entity, it knows what their initial values were, and if they differ from the current ones, the entity is considered “dirty.” A sample code follows.

Code Listing 97

//load some entity. var tool = ctx.Tools.FirstOrDefault();

ctx.SaveChanges(); //0 //change something. tool.Name += "_changed";

//send changes. var affectedRecords = ctx.SaveChanges(); //1 |

As you can see, no separate update method is necessary, nor does it exist, since all types of changes (inserts, updates, and deletes) are detected automatically and performed by the SaveChanges method. SaveChanges still needs to be called, and it will return the combined count of all inserted and updated entities. If some sort of integrity constraint is violated, then an exception will be thrown, and this needs to be dealt with appropriately.

Deleting entities

When you have a reference to a loaded entity, you can mark it as deleted, so that when changes are persisted, EF will delete the corresponding record. Deleting an entity in EF consists of removing it from the DbSet<T> collection.

Code Listing 98

//load some entity. var tool = ctx.Tools.FirstOrDefault();

//remove the entity. ctx.Tools.Remove(tool);

//send changes. var affectedRecords = ctx.SaveChanges(); //1 |

Of course, SaveChanges still needs to be called to make the changes permanent. If any integrity constraint is violated, an exception will be thrown.

Note: Entity Framework will apply all the pending changes (inserts, updates, and deletes) in an appropriate order, including entities that depend on other entities.

Inspecting the tracked entities

When we talked about the local cache, you may have asked yourself where this cache is—and what can be done with it.

You access the local cache entry for an entity with the Entry method. This returns an instance of EntityEntry, which contains lots of useful information, such as the current state of the entity (as seen by the context), the initial and current values, and so on.

Code Listing 99

//load some entity. var tool = ctx.Tools.FirstOrDefault();

//get the cache entry. var entry = ctx.Entry(tool); //get the entity state. var state = entry.State; //EntityState.Unchanged //get the original value of the Name property. var originalName = entry.OriginalValues["Name"] as String; //Visual Studio 2017 //change something. tool.Name += "_changed"; //get the current state state = entry.State; //EntityState.Modified //get the current value of the Name property. var currentName = entry.CurrentValues["Name"] as String; //Visual Studio 2017_changed |

If you want to inspect all the entries currently being tracked, there is the ChangeTracker property.

Code Listing 100

//get all the added entities of type Project. var addedProjects = ctx .ChangeTracker .Entries() .Where(x => x.State == EntityState.Added) .Select(x => x.Entity) .OfType<Project>(); |

Using SQL to make changes

Sometimes you need to do bulk modifications, and, in this case, nothing beats good old SQL. EF Core offers the ExecuteSqlCommand in the Database property that you can use just for that:

Code Listing 101

var rows = ctx.Database.ExecuteSqlCommand($"DELETE FROM Project WHERE ProjectId = {id}"); |

As you can see, you can even use interpolated strings, EF Core will translate them to safe parameterized strings.

Firing events when an entity’s state changes

There’s a special infrastructure interface called ILocalViewListener that is registered in Entity Framework and is called whenever the state of an entity changes (like when it’s about to be saved, deleted, updated, etc.). We use it like this:

Code Listing 102

var events = ctx.GetService<ILocalViewListener>(); events.RegisterView((entry, state) => { //entry contains the entity’s details. //state is the new state. }); |

Cascading deletes

Two related tables can be created in the database in such a way that when one record of the parent table is deleted, all corresponding records in the child table are also deleted. This is called cascading deletes.

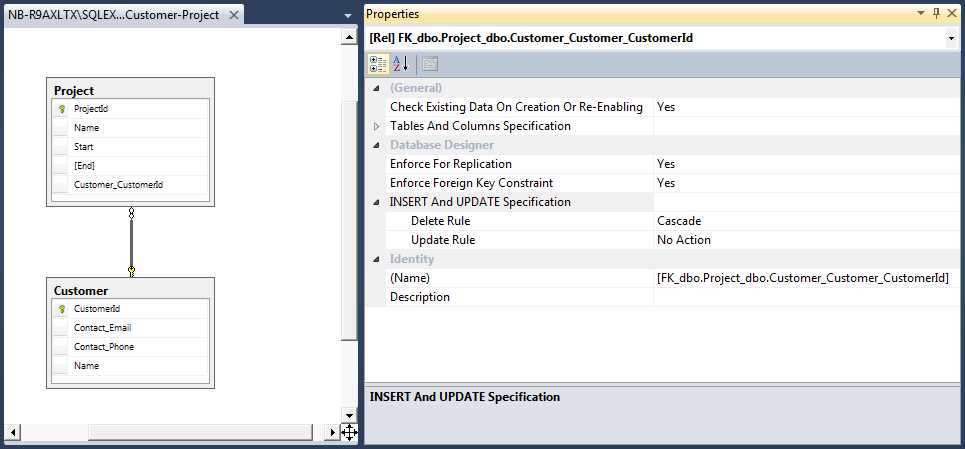

Figure 17: Cascading deletes

This is useful for automatically keeping the database integrity. If the database didn’t do this for us, we would have to do it manually; otherwise, we would end up with orphan records. This is only useful for parent-child or master-detail relationships where one endpoint cannot exist without the other. Not all relationships should be created this way; for example, when the parent endpoint is optional, we typically won’t cascade. Think of a customer-project relationship: it doesn’t make sense to have projects without a customer. On the other hand, it does make sense to have a bug without an assigned developer.

When Entity Framework creates the database, it will create the appropriate cascading constraints depending on the mapping.

Figure 18: A cascade delete

As of now, EF applies a convention for that, but it can be overridden by fluent mapping.

Table 2

Relationship | Default Cascade |

|---|---|

One-to-one | No |

One-to-many | Only if the one endpoint is required |

Many-to-one | No |

We can explicitly configure the cascading option in fluent configuration like this:

Code Listing 103

//when deleting a Project, delete its ProjectDetail. builder .Entity<Project>() .HasOne(b => b.Detail) .WithOne(d => d.Project) .OnDelete(DeleteBehavior.Cascade); //when deleting a ProjectResource, do not delete the Project. builder .Entity<ProjectResource>() .HasOne(x => x.Project) .WithMany(x => x.ProjectResources) .OnDelete(DeleteBehavior.SetNull); //when deleting a Project, delete its ProjectResources. builder .Entity<Project>() .HasMany(x => x.ProjectResources) .WithOne(x => x.Project) .OnDelete(DeleteBehavior.Cascade); |

Tip: You can have multiple levels of cascades, just make sure you don’t have circular references.

Note: Cascade deletes occur at the database level; Entity Framework does not issue any SQL for that purpose.

Refreshing entities

When a record is loaded by EF as the result of a query, an entity is created and placed in local cache. When a new query is executed that returns records associated with an entity already in local cache, no new entity is created; instead, the one from the cache is returned. This has an occasionally undesirable side effect: even if something changed in the entity’s record, the local entity is not updated. This is an optimization that Entity Framework performs, but sometimes it can lead to unexpected results. If we want to make sure we have the latest data, we need to force an explicit refresh, first, removing the entity from the local cache:

Code Listing 104

//load some entity. var project = ctx.Projects.Find(1); //set it to detached. ctx.Entry(project).State = EntityState.Detached; //time passes…

//load entity again. project = ctx.Projects.Find(1); |

Entity Framework Core allows us to refresh it:

Code Listing 105

ctx.Entry(project).Reload(); |

Even for just a specific property:

Code Listing 106

ctx .Entry(project) .Property(x => x.Name) .EntityEntry .Reload(); |

Or collection:

Code Listing 107

ctx .Entry(customer) .Collection(x => x.Projects) .EntityEntry .Reload(); |

Concurrency control

Optimistic concurrency control is a method for working with databases that assumes multiple transactions can complete without affecting each other; no locking is required. Each update transaction will check to see if any records have been modified in the database since they were read, and if so, will fail. This is very useful for dealing with multiple accesses to data in the context of web applications.

There are two ways for dealing with the situation where data has been changed:

- First one wins: The second transaction will detect that data has been changed, and will throw an exception.

- Last one wins: While it detects that data has changed, the second transaction chooses to overwrite it.

Entity Framework supports both of these methods.

First one wins

We have an entity instance obtained from the database, we change it, and we tell the EF context to persist it. Because of optimistic concurrency, the SaveChanges method will throw a DbUpdateConcurrencyException if the data was changed, so make sure you wrap it in a try…catch.

Code Listing 108

try { ctx.SaveChanges(); } catch (DbUpdateConcurrencyException) { //the record was changed in the database, notify the user and fail. } |

The “first one wins” approach is just this: fail if a change has occurred.

Last one wins

For this one, we will detect that a change has been made, and we’ll overwrite it explicitly. However, in Entity Framework Core, we cannot do this automatically in an easy way.

Applying optimistic concurrency

Entity Framework by default does not perform the optimistic concurrency check. You can enable it by choosing the property or properties whose values will be compared with the current database values. This is done by applying a ConcurrencyCheckAttribute when mapping by attributes.

Code Listing 109

public class Project { [Concurrency][ConcurrencyCheck] public DateTime Timestamp { get; set; } } |

Or in mapping by code.

Code Listing 110

protected override void OnModelCreating(ModelBuilder modelBuilder) { modelBuilder .Entity<Project>() .Property(x => x.Name) .IsConcurrencyToken(); } |

What happens is this: when EF generates the SQL for an UPDATE operation, it will not only include a WHERE restriction for the primary key, but also for any properties marked for concurrency check, comparing their columns with the original values.

Figure 19: An update with a concurrency control check

If the number of affected records is not 1, this will likely be because the values in the database will not match the original values known by Entity Framework, because they have been modified by a third party outside of Entity Framework.

SQL Server has a data type whose values cannot be explicitly set, but instead change automatically whenever the record they belong to changes: ROWVERSION. Other databases offer similar functionality.

Because Entity Framework has a nice integration with SQL Server, columns of type ROWVERSION are supported for optimistic concurrency checks. For that, we need to map one such column into our model as a timestamp. First, we’ll do so with attributes by applying a TimestampAttribute to a property, which needs to be of type byte array, and doesn’t need a public setter.

Code Listing 111

[Timestamp] public byte [] RowVersion { get; protected set; } |

And, for completeness, with fluent configuration.

Code Listing 112

modelBuilder .Entity<Project>() .Property(x => x.RowVersion) .IsRowVersion(); |

The behavior of TimestampAttribute is exactly identical to that of ConcurrencyCheckAttribute, but there can be only one property marked as timestamp per entity, and ConcurrencyCheckAttribute is not tied to a specific database.

Detached entities

A common scenario in web applications is this: you load some entity from the database, store it in the session, and in a subsequent request, get it from there and resume using it. This is all fine except that if you are using Entity Framework Core, you won’t be using the same context instance on the two requests. This new context knows nothing about this instance. In this case, it is said that the entity is detached in relation to this context. The effect is that any changes to this instance won’t be tracked, and any lazy loaded properties that weren’t loaded when it was stored in the session won’t be loaded.

What we need to do is associate this instance with the new context.

Code Listing 113

//retrieve the instance from the ASP.NET context. var project = Session["StoredProject"] as Project; var ctx = new ProjectsContext(); //attach it to the current context with a state of unchanged. ctx.Entry(project).State = EntityState.Unchanged; |

After this, everything will work as expected.

If, however, we need to attach a graph of entities in which some may be new and others modified, we can use the Graph API introduced in Entity Framework Core. For this scenario, Entity Framework lets you traverse through all of an entity’s associated entities and set each’s state individually. This is done using the TrackGraph method of the DbContext’s ChangeTracker member:

Code Listing 114

ctx.ChangeTracker.TrackGraph(rootEntity, node => { if (node.Entry.Entity is Project) { if ((node.Entry.Entity as Project).ProjectId != 0) { node.Entry.State = EntityState.Unchanged; } else { //other conditions } } ); |

Validation

Unlike previous versions, Entity Framework Core does not perform validation of the tracked entities when the SaveChanges method is called. Entity Framework pre-Core used to validate entities with the Data Annotations API. Fortunately, it is easy to bring this behavior back if we override SaveChanges and plug in our validation algorithm—in this case, Data Annotations validation:

Code Listing 115

public override int SaveChanges() { var serviceProvider = GetService<IServiceProvider>(); var items = new Dictionary<object, object>();

foreach (var entry in ChangeTracker.Entries().Where(e => (e.State == EntityState.Added) || (e.State == EntityState.Modified)) { var entity = entry.Entity; var context = new ValidationContext(entity, serviceProvider, items); var results = new List<ValidationResult>();

if (!Validator.TryValidateObject(entity, context, results, true)) { foreach (var result in results) { if (result != ValidationResult.Success) { throw new ValidationException(result.ErrorMessage); } } } }

return base.SaveChanges(); } |

In order for the GetService extension method to be recognized, you need to add a namespace reference to Microsoft.EntityFrameworkCore.Infrastructure. This is possible because DbContext implements IInfrastructure<IServiceProvider>, which exposes the internal service provider.

In order to validate entities before committing them to the database, we use the change tracker to loop through each entity that has been added or updated in the context. Then we use Validator.TryValidateObject to check for validation errors. If we find a validation error, we throw a ValidationException.

Because we call the base SaveChanges method, if there are no validation errors, everything works as expected.

A validation result consists of instances of DbEntityValidationResult, of which there will be only one per invalid entity. This class offers the following properties.

Table 3: Validation result properties

Property | Purpose |

The entity to which this validation refers. | |

Indicates whether the entity is valid or not. | |

A collection of individual errors. |

The ValidationErrors property contains a collection of DbValidationError entries, each exposing the following.

Table 4: Result error properties

Property | Purpose |

The error message. | |

The name of the property on the entity that was considered invalid (can be empty if what was considered invalid was the entity as a whole). |

If we attempt to save an entity with invalid values, a DbEntityValidationException will be thrown, and inside of it, there is the EntityValidationErrors collection, which exposes all DbEntityValidationResult found.

Code Listing 116

try { //try to save all changes. ctx.SaveChanges(); } catch (DbEntityValidationException ex) { //validation errors were found that prevented saving changes. var errors = ex.EntityValidationErrors.ToList(); } |

Validation attributes

Similar to the way we can use attributes to declare mapping options, we can also use attributes for declaring validation rules. A validation attribute must inherit from ValidationAttribute in the System.ComponentModel.DataAnnotations namespace and override one of its IsValid methods. There are some simple validation attributes we can use out of the box that are in no way tied to Entity Framework.

Table 5: Validation attributes

Validation Attribute | Purpose |

|---|---|

Compares two properties and fails if they are different. | |

Executes a custom validation function and returns its value. | |

Checks whether a string property has a length greater than a given value. | |

Checks whether a string property has a length smaller than a given value. | |

Checks whether the property’s value is included in a given range. | |

Checks whether a string matches a given regular expression. | |

Checks whether a property has a value; if the property is of type string, also checks whether it is empty. | |

Checks whether a string property’s length is contained within a given threshold. | |

Checks whether a string property (typically a password) matches the requirements of the default Membership Provider. |

It is easy to implement a custom validation attribute. Here we can see a simple example that checks whether a number is even.

Code Listing 117

[AttributeUsage(AttributeTargets.Property, AllowMultiple = false, Inherited = true)] public sealed class IsEvenAttribute : ValidationAttribute { protected override ValidationResult IsValid(object value, ValidationContext validationContext) { //check if the value is null or empty. if ((value != null) && (!string.IsNullOrWhiteSpace(value.ToString()))) { //check if the value can be converted to a long one. var number = Convert.ToDouble(value); //fail if the number is even. if ((number % 2) == 0) { return new ValidationResult(ErrorMessage, new [] { validationContext.MemberName }); } } return ValidationResult.Success; } } |

It can be applied to any property whose type can be converted to a long integer—it probably doesn’t make sense in the case of a budget, but let’s pretend it does.

Code Listing 118

[IsEven(ErrorMessage = "Number must be even")] public int Number { get; set; } |

We can also supply a custom validation method by applying a CustomValidationAttribute. Let’s see how the same validation (“is even”) can be implemented using this technique. First, use the following attribute declaration.

Code Listing 119

[CustomValidation(typeof(CustomValidationRules), "IsEven", ErrorMessage = "Number must be even")] public int Number { get; set; } |

Next, use the following actual validation rule implementation.

Code Listing 120

public static ValidationResult IsEven(Object value, ValidationContext context) { //check if the value is not null or empty. if ((value != null) && (!string.IsNullOrWhiteSpace(value.ToString()))) { //check if the value can be converted to a long one. var number = Convert.ToDouble(value); //fail if the number is even. if ((number % 2) == 0) { return new ValidationResult(ErrorMessage, new [] { validationContext.MemberName }); } return ValidationResult.Success; } } |

I chose to implement the validation function as static, but it is not required. In that case, the class where the function is declared must be safe to instantiate (not abstract with a public parameterless constructor).

Implementing self-validation

Another option for performing custom validations lies in the IValidatableObject interface. By implementing this interface, an entity can be self-validatable; that is, all validation logic is contained within itself. Let’s see how.

Code Listing 121

public class Project : IValidatableObject { //other members go here. public IEnumerable<ValidationResult> Validate(ValidationContext context) { if (ProjectManager == null) { yield return new ValidationResult("No project manager specified"); } if (Developers.Any() == false) { yield return new ValidationResult("No developers specified"); } if ((End != null) && (End.Value < Start)) { yield return new ValidationResult("End of project is before start"); } } } |

Wrapping up

You might have noticed that all these custom validation techniques—custom attributes, custom validation functions, and IValidatableObject implementation—all return ValidationResult instances, whereas Entity Framework Code First exposes validation results as collections of DbEntityValidationResult and DbValidationError. Don’t worry: Entity Framework will take care of it for you!

So, which validation option is best? In my opinion, all have strong points, and all can be used together. I’ll just leave some final remarks:

- If a validation attribute is sufficiently generic, it can be reused in many places.

- When we look at a class that uses attributes to express validation concerns, it is easy to see what we want.

- It also makes sense to have general purpose validation functions available as static methods, which may be invoked from either a validation attribute or otherwise.

- Finally, a class can self-validate in ways that are hard or even impossible to express using attributes. For example, think of properties whose values depend on other properties’ values.

Tip: Keep in mind that this only works because we explicitly called Validator.TryValidateObject, since EF Core no longer automatically performs validation.

Transactions

Transactions in Entity Framework Core come in three flavors:

- Implicit: The method SaveChanges creates a transaction for wrapping all change sets that it will send to the database, if no ambient transaction exists. This is necessary for properly implementing a Unit of Work, where either all or no changes are applied simultaneously.

- Explicit: We need to start the transaction explicitly ourselves, and then either commit or “roll it back.”

- External: A transaction was started outside of Entity Framework, yet we want it to use it.

You should use transactions primarily for two reasons:

- For maintaining consistency when performing operations that must be simultaneously successful (think of a bank transfer where money leaving an account must enter another account).

- For assuring identical results for read operations where data can be simultaneously accessed and possibly changed by third parties.

In order to start an explicit transaction on a relational database, you need to call BeginTransaction or BeginTransactionAsync on the Database property of the context:

Code Listing 122

ctx.Database.BeginTransaction(); |

This actually returns a IDbContextTransaction object, which wraps the ADO.NET transaction object (DbTransaction).

Likewise, you either commit or roll it back using methods in Database:

Code Listing 123

if (/*some condition*/) { ctx.Database.CommitTransaction(); } else { ctx.Database.RollbackTransaction(); } |

Calling RollbackTransaction explicitly is redundant if you just dispose of the transaction returned by BeginTransaction without actually calling CommitTransaction.

If, on the other hand, you have a transaction started elsewhere, you need to pass the DbTransaction instance to the UseTransaction method of IRelationalTransactionManager:

Code Listing 124

ctx.GetService<IRelationalTransactionManager>().UseTransaction(tx); |

Or, pass it to the underlying DbConnection instance:

Code Listing 125

var con = ctx.Database.GetDbConnection(); con.Transaction = tx; |

Connection resiliency

Another thing you need to be aware of is that connections may be dropped, and commands may fail due to broken connections. This will happen not only in cloud scenarios, but also elsewhere. You need to be aware of this possibility and program defensively.

Entity Framework Core—as, to some degree, its predecessor—offers something called connection resiliency. In a nutshell, it is a mechanism by which EF will retry a failed operation a number of times, with some interval between them, until it either succeeds or fails. This only applies to what the provider considers transient errors.

This needs to go in two stages:

- We first need to configure it in the provider-specific configuration code:

Code Listing 126

protected override void OnConfiguring(DbContextOptionsBuilder optionsBuilder) { optionsBuilder .UseSqlServer( connectionString: _nameOrConnectionString, sqlServerOptionsAction: opts => { opts.EnableRetryOnFailure(3, TimeSpan.FromSeconds(3), new int[] {}); }); ); base.OnConfiguring(optionsBuilder); } |

- Then we need to register all the operations that we want to retry:

Code Listing 127

var strategy = ctx.Database.CreateExecutionStrategy(); strategy.Execute(() => { using (var tx = ctx.Database.BeginTransaction()) { tx.Projects.Add(new Project { Name = "Big Project", Customer = new Customer { CustomerId = 1 }, Start = DateTime.UtcNow }); tx.Commit(); } }); |

This tells EF to retry this operation up to three times with an interval of three seconds between each. The last parameter to EnableRetryOnFailure is an optional list of provider-specific error codes that are to be treated as transient errors. Instead of executing an operation immediately, we go through the strategy object.

- 1800+ high-performance UI components.

- Includes popular controls such as Grid, Chart, Scheduler, and more.

- 24x5 unlimited support by developers.