CHAPTER 1

Setting Up

Before we start

Before you start using EF Core, you need to have its assemblies deployed locally. The distribution model followed by Microsoft and a number of other companies does not depend on old-school Windows installers, but instead relies on new technologies such as NuGet and Git. We’ll try to make sense of each of these options in a moment, but before we get to that, make sure you have Visual Studio 2015 or 2017 installed (any edition including Visual Studio Community Edition will work), as well as SQL Server 2012 (any edition, including Express) or higher. In SQL Server Management Studio, create a new database called Succinctly.

Getting Entity Framework Core from NuGet

NuGet is to .NET package management what Entity Framework is to data access. In a nutshell, it allows Visual Studio projects to have dependencies on software packages—assemblies, source code files, PowerShell scripts, etc.—stored in remote repositories. Being highly modular, EF comes in a number of assemblies, which are deployed out-of-band, unrelated to regular .NET releases. In order to install it to an existing project, first run the Package Manager Console from Tools > Library Package Manager and enter the following command.

Install-package Microsoft.EntityFrameworkCore

Because of the new modular architecture, you will also need the provider for SQL Server (Microsoft.EntityFramework.MicrosoftSqlServer), which is no longer included in the base package (Microsoft.EntityFramework):

Install-package Microsoft.EntityFrameworkCore.SqlServer

This is by far the preferred option for deploying Entity Framework Core, the other being getting the source code from GitHub and manually building it. I’ll explain this option next.

Getting Entity Framework Core from GitHub

The second option, for advanced users, is to clone the Entity Framework Core repository on GitHub, build the binaries yourself, and manually add a reference to the generated assembly.

First things first, let’s start by cloning the Git repository using your preferred Git client.

Code Listing 1

Next, build everything from the command line using the following two commands.

Code Listing 2

build /t:RestorePackages /t:EnableSkipStrongNames build |

You can also fire up Visual Studio 2015 or 2017 and open the EntityFramework.sln solution file. This way, you can do your own experimentations with the source code, compile the debug version of the assembly, run the unit tests, etc.

Contexts

A context is a non-abstract class that inherits from DbContext. This is where all the fun happens: it exposes collections of entities that you can manipulate to return data from the store or add stuff to it. It needs to be properly configured before it is used. You will need to implement a context and make it your own, by making available your model entities and all of the necessary configuration.

Infrastructure methods

Entity Framework Core’s DbContext class has some infrastructure methods that it calls automatically at certain times:

- OnConfiguring: Called automatically when the context needs to configure itself—setting up providers and connection strings, for example—giving developers a chance to intervene.

- OnModelCreating: Called automatically when Entity Framework Core is assembling the data model.

- SaveChanges: Called explicitly when we want changes to be persisted to the underlying data store. Returns the number of records affected by the saving operations.

Make yourself acquainted with these methods, as you will see them several times throughout the book.

Configuring the database provider

Entity Framework is database-agnostic, but that means that each interested party—database manufacturers or others—must release their own providers so that Entity Framework can use them. Out of the box, Microsoft makes available providers for SQL Server 2012, including Azure SQL Database, SQL Server Express, and SQL Server Express LocalDB, but also for SQLite and In Memory. The examples in this book will work on any of these providers. Make sure you have at least one of them installed and that you have the appropriate administrative permissions.

Entity Framework determines which connection to use through a new infrastructure method of DbContext, OnConfiguring, where we can explicitly configure it. This is substantially different from previous versions. Also, you can pass the configuration using the constructor that takes a DbContextOptions parameter.

SQL Server

Before we can connect to SQL Server, we need to have locally the Microsoft.EntityFrameworkCore.SqlServer NuGet package. See Appendix A for other options.

Configuring the service provider

An Entity Framework Core context uses a service provider to keep a list of its required services. When you configure a specific provider, the process registers all of its specific services, which are then combined with the generic ones. It is possible to supply our own service provider or just replace one or more of the services. We will see an example of this.

Sample domain model

Let’s consider the following scenario as the basis for our study.

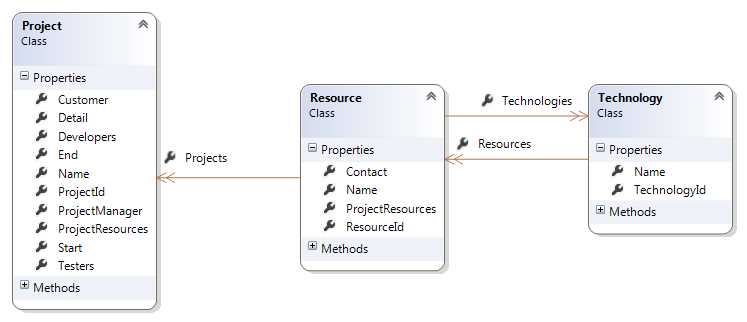

Figure 1: The domain model

You will find all these classes in the accompanying source code. Let’s try to make some sense out of them:

- A Customer has a number of Projects.

- Each Project has a collection of ProjectResources, belongs to a single Customer, and has a ProjectDetail with additional information.

- A ProjectDetail refers to a single Project.

- A ProjectResource always points to an existing Resource and is assigned to a Project with a given Role.

- A Resource knows some Technologies and can be involved in several Projects.

- A Technology can be collectively shared by several Resources.

- Both Customers and Resources have Contact information.

Note: You can find the full source code in my Git repository here.

Core concepts

Before a class model can be used to query a database or to insert values into it, Entity Framework needs to know how it should translate entities (classes, properties, and instances) back and forth into the database (specifically, tables, columns, and records). For that, it uses a mapping, for which two APIs exist. More on this later, but first, some fundamental concepts.

Contexts

Again, a context is a class that inherits from DbContext and exposes a number of entity collections in the form of DbSet<T> properties. Nothing prevents you from exposing all entity types, but normally you only expose aggregate roots, because these are the ones that make sense querying on their own. Another important function of a context is to track changes to entities so that when we are ready to save our changes, it knows what to do. Each entity tracked by the context will be in one of the following states: unchanged, modified, added, deleted, or detached. A context can be thought of as a sandbox in which we can make changes to a collection of entities and then apply those changes with one save operation.

An example context might be the following.

Code Listing 3

public class ProjectsContext : DbContext { public DbSet<Resource> Resources { get; private set; } public DbSet<Resource> Resources { get; private set; } public DbSet<Project> Projects { get; private set; } public DbSet<Customer> Customers { get; private set; } public DbSet<Technology> Technologies { get; private set; } } |

Note: Feel free to add your own methods, business or others, to the context class.

The DbContext class offers two public constructors, allowing the passing of context options:

Code Listing 4

public class ProjectsContext : DbContext { public ProjectsContext(string connectionString) : base (GetOptions(connectionString)) { } public ProjectsContext(DbContextOptions options) : base(options) { } private static DbContextOptions GetOptions(string connectionString) { var modelBuilder = new DbContextOptionsBuilder(); return modelBuilder.UseSqlServer(connectionString).Options; } } |

Context options include the specific database provider to use, its connection string, and other applicable properties.

This is just one way to pass a connection string to a context, we can also use the OnConfiguring method that will be described shortly.

Entities

At the very heart of the mapping is the concept of an entity. An entity is just a class that is mapped to an Entity Framework context, and has an identity (a property that uniquely identifies instances of it). In domain-driven design (DDD) parlance, it is said to be an aggregate root if it is meant to be directly queried. Think of an entity detail that is loaded together with an aggregate root and not generally considerable on its own, such as project details or customer addresses. An entity is usually persisted on its own table and may have any number of business or validation methods.

Code Listing 5

public class Project { public int ProjectId { get; set; }

public string Name { get; set; }

public DateTime Start { get; set; }

public DateTime? End { get; set; }

public ProjectDetail Detail { get; set; }

public Customer Customer { get; set; } public void AddResource(Resource resource, Role role) { resource.ProjectResources.Add(new ProjectResource() { Project = this, Resource = resource, Role = role }); }

public Resource ProjectManager { get { return ProjectResources.ToList() .Where(x => x.Role == Role.ProjectManager) .Select(x => x.Resource).SingleOrDefault(); } }

public IEnumerable<Resource> Developers { get { return ProjectResources.Where(x => x.Role == Role.Developer) .Select(x => x.Resource).ToList(); } }

public IEnumerable<Resource> Testers { get { return ProjectResources.Where(x => x.Role == Role.Tester) .Select(x => x.Resource).ToList(); } }

public ICollection<ProjectResource> ProjectResources { get; } = new HashSet<ProjectResource>();

public override String ToString() { return Name; } } |

Here you can see some patterns that we will be using throughout the book:

- An entity needs to have at least a public parameterless constructor.

- An entity always has an identifier property, which has the same name and ends with Id.

- Collections are always generic, have protected setters, and are given a value in the constructor in the form of an actual collection (like HashSet<T>).

- Calculated properties are used to expose filtered sets of persisted properties.

- Business methods are used for enforcing business rules.

- A textual representation of the entity is supplied by overriding the ToString.

Tip: Seasoned Entity Framework developers will notice the lack of the virtual qualifier for properties. It is not required since Entity Framework Core 1.1 does not support lazy properties, as we will see.

Tip: In the first version of Entity Framework Core, complex types are not supported, so nonscalar properties will always be references to other entities or to collections of them.

A domain model where its entities have only properties (data) and no methods (behavior) is sometimes called an Anemic Domain Model. You can find a good description for this anti-pattern on Martin Fowler’s website.

Complex types

Complex types, or owned entities, were introduced in EF Core 2.0. They provide a way to better organize our code by grouping together properties in classes. These classes are not entities because they do not have identity (no primary key) and their contents are not stored in a different table, but on the table of the entity that declares them. A good example is an Address class: it can have several properties and can be repeated several times (e.g., work address, personal address).

Scalar properties

Scalars are simple values like strings, dates, and numbers. They are where actual entity data is stored—in relational databases and table columns—and can be of one of any of the following types.

Table 1 : Scalar Properties

.NET Type | SQL Server Type | Description |

|---|---|---|

Boolean | Single bit | |

Byte | Single byte (8 bits) | |

Char | CHAR, | ASCII or UNICODE char (8 or 16 bits) |

Int16 | Short integer (16 bits) | |

Int32 | Integer (32 bits) | |

Int64 | Long (64 bits) | |

Single | Floating point number (32 bits) | |

Double | Double precision floating point number (64 bits) | |

Decimal | SMALLMONEY | Currency (64 bits) or small currency (32 bits) |

Guid | Globally Unique Identifier (GUID) | |

DateTime | DATE, | Date with or without time |

DateTimeOffset | Date and time with timezone information | |

TimeSpan | Time | |

String | ASCII (8 bits per character), UNICODE (16 bits) or XML character string. Can also represent a Character Long Object (CLOB) | |

Byte[] | VARBINARY , | Binary Large Object (BLOB) |

Enum | Enumerated value |

Tip: Spatial data types are not supported yet, but they will be in a future version.

The types Byte, Char, and String can have a maximum length specified. A value of -1 translates to MAX.

All scalar types can be made “nullable,” meaning they might have no value set. In the database, this is represented by a NULL value.

Scalar properties need to have both a getter and a setter, but the setter can have a more restricted visibility than the getter: internal, protected internal, or protected.

Some examples of scalar properties are as follows.

Code Listing 6

public class Project { public int ProjectId { get; set; }

public string Name { get; set; } public DateTime Start { get; set; }

public DateTime? End { get; set; } } |

All public properties are, by default, included in the model that Entity Framework uses to represent its entities. You can exclude them either by using attributes or by code configuration.

Identity properties

One or more of the scalar properties of your entity must represent the underlying table’s primary key, which can be single or composite.

Primary key properties can only be of one of the basic types (any type in Table 1, except arrays and enumerations), but cannot be complex types or other entity’s types.

Fields

New since Entity Framework Core 1.1 is the possibility of mapping fields, of any visibility. This comes in handy because it allows better encapsulation of inner data and helps prevent bad data. Fields, unlike public properties, are not automatically mapped and have to be explicitly added to the model. More on this in a moment.

References

A reference from one entity to another defines a bidirectional relation. There are two types of reference relations:

- Many-to-one: Several instances of an entity can be associated with the same instance of another type (such as projects that are owned by a customer).

Figure 2: Many-to-one relationship

- One-to-one: An instance of an entity is associated with another instance of another entity; this other instance is only associated with the first one (such as a project and its detail).

Figure 3: One-to-one relationship

In EF, we represent an association by using a property of the other entity’s type.

Figure 4: References: one-to-one, many-to-one

We call an entity’s property that refers to another entity as an endpoint of the relation between the two entities.

Code Listing 7

public class Project { //one endpoint of a many-to-one relation. public Customer Customer { get; set; } //one endpoint of a one-to-one relation. public ProjectDetail Detail { get; set; } } public class ProjectDetail { //the other endpoint of a one-to-one relation. public Project Project { get; set; } } public class Customer { //the other endpoint of a many-to-one relation. public ICollection<Project> Projects { get; protected set; } } |

Note: By merely looking at one endpoint, we cannot immediately tell what its type is (one-to-one or many-to-one), we need to look at both endpoints.

Collections

Collections of entities represent one of two possible types of bidirectional relations:

- One-to-many: A single instance of an entity is related to multiple instances of some other entity’s type (such as a project and its resources).

Figure 5: One-to-many relationship

- Many-to-many: A number of instances of a type can be related with any number of instances of another type (such as resources and the technologies they know). Entity Framework Core currently does not support this kind of relation directly.

Figure 6: Many-to-many relationship

Figure 7: Collections: one-to-many

Entity Framework only supports declaring collections as ICollection<T> (or some derived class or interface) properties. In the entity, we should always initialize the collections properties in the constructor.

Code Listing 8

public class Project { public Project() { ProjectResources = new HashSet<ProjectResource>(); } public ICollection<ProjectResource> ProjectResources { get; protected set; } } |

Note: References and collections are collectively known as navigation properties, as opposed to scalar properties.

Tip: As of now, Entity Framework Core does not support many-to-many relations. The way to go around this limitation is to have two one-to-many relations, which implies that we need to map the association table.

Shadow properties

Entity Framework Core introduces a new concept, shadow properties, which didn’t exist in previous versions. In a nutshell, a shadow property is a column that exists in a table but has no corresponding property in the POCO class. Whenever Entity Framework fetches an entity of a class containing shadow properties, it asks for the columns belonging to them.

What are they used for, then? Well, shadow properties are kept in Entity Framework’s internal state for the loaded entities, and can be used when inserting or updating records, for example, to set auditing fields. Consider this case where we have an interface for specifying entities to be auditable, let’s call it, then, IAuditable:

Code Listing 9

public interface IAuditable { } public class ProjectsContext : DbContext { public Func<string> UserProvider { get; set; } = () => WindowsIdentity.GetCurrent().Name; public Func<DateTime> TimestampProvider { get; set ; } = () => DateTime.UtcNow; public DbSet<Project> Projects { get; protected set; } protected override void OnModelCreating(ModelBuilder modelBuilder) { foreach (var entity in modelBuilder.Model.GetEntityTypes() .Where(x => typeof(IAuditable).IsAssignableFrom(x.ClrType))) { entity.AddProperty("CreatedBy", typeof(string)); entity.AddProperty("CreatedAt", typeof(DateTime)); entity.AddProperty("UpdatedBy", typeof(string)); entity.AddProperty("UpdatedAt", typeof(DateTime?)); } base.OnModelCreating(modelBuilder); } public override int SaveChanges() { foreach (var entry in ChangeTracker.Entries().Where(e => e.State == EntityState.Added || e.State == EntityState.Modified)) { if (entry.Entity is IAuditable) { if (entry.State == EntityState.Added) { entry.Property("CreatedBy").CurrentValue = UserProvider(); entry.Property("CreatedAt").CurrentValue = TimestampProvider(); } else { entry.Property("UpdatedBy").CurrentValue = UserProvider(); entry.Property("UpdatedAt").CurrentValue = TimestampProvider(); } } } return base.SaveChanges(); } } |

For the WindowsIdentity class we need to add a reference to the System.Security.Principal.Windows NuGet package. By default, we will be getting the current user’s identity from it.

In the OnModelCreating method, we look for any classes implementing IAuditable, and for each, we add a couple of auditing properties. Then in SaveChanges, we iterate through all of the entities waiting to be persisted that implement IAuditable and we set the audit values accordingly. To make this more flexible—and unit-testable—I made the properties UserProvider and TimestampProvider configurable, so that you change the values that are returned.

Querying shadow properties is also possible, but it requires a special syntax—remember, we don’t have “physical” properties:

Code Listing 10

var resultsModifiedToday = ctx .Projects .Where(x => EF.Property<DateTime>(x, "UpdatedAt") == DateTime.Today) .ToList(); |

Mapping by attributes

Overview

The most commonly used way to express our mapping intent is to apply attributes to properties and classes. The advantage is that, by merely looking at a class, one can immediately infer its database structure.

Schema

Unless explicitly set, the table where an entity type is to be stored is determined by a convention (more on this later on), but it is possible to set the type explicitly by applying a TableAttribute to the entity’s class.

Code Listing 11

[Table("MY_SILLY_TABLE", Schema = "dbo")] public class MySillyType { } |

The Schema property is optional, and should be used to specify a schema name other than the default. A schema is a collection of database objects (tables, views, stored procedures, functions, etc.) in the same database. In SQL Server, the default schema is dbo.

For controlling how a property is stored (column name, physical order, and database type), we apply a ColumnAttribute.

Code Listing 12

[Column(Order = 2, TypeName = "VARCHAR")] public string Surname { get; set; } [Column(Name = "FIRST_NAME", Order = 1, TypeName = "VARCHAR")] public string FirstName { get; set; } |

If the TypeName is not specified, Entity Framework will use the engine’s default for the property type. SQL Server will use NVARCHAR for String properties, INT for Int32, BIT for Boolean, etc. We can use it for overriding this default.

The Order applies a physical order to the generated columns that might be different from the order by which properties appear on the class. When the Order property is used, there should be no two properties with the same value in the same class.

Marking a scalar property as mandatory requires the usage of the RequiredAttribute.

Code Listing 13

[Required] public string Name { get; set; } |

Tip: When this attribute is applied to a String property, it not only prevents the property from being null, but also from taking an empty string.

Tip: For value types, the actual property type should be chosen appropriately. If the column is non-nullable, one should not choose a property type that is nullable, such as Int32?.For a required entity reference, the same rule applies.

Code Listing 14

[Required] public Customer Customer { get; set; } |

Setting the maximum allowed length of a string column is achieved by means of the MaxLengthAttribute.

Code Listing 15

[MaxLength(50)] public string Name { get; set; } |

The MaxLengthAttribute can also be used to set a column as being a CLOB, a column containing a large amount of text. SQL Server uses the types NVARCHAR(MAX) (for UNICODE) and VARCHAR(MAX) (ASCII). For that, we pass a length of -1.

Code Listing 16

[MaxLength(-1)] public string LargeText { get; set; } |

It can also be used to set the size of a BLOB (in SQL Server, VARBINARY) column.

Code Listing 17

[MaxLength(-1)] public byte[] Picture { get; set; } |

Like in the previous example, the -1 size will effectively be translated to MAX.

Ignoring a property and having Entity Framework never consider it for any operations is as easy as setting a NotMappedAttribute on the property.

Code Listing 18

[NotMapped] public string MySillyProperty { get; set; } |

Fully ignoring a type, including any properties that might refer to it, is also possible by applying the NotMappedAttribute to its class instead.

Code Listing 19

[NotMapped] public class MySillyType { } |

Fields

Mapping fields needs to be done using mapping by code, which we’ll cover shortly.

Primary keys

While database tables don’t strictly require a primary key, Entity Framework requires it. Both single-column and multicolumn (composite) primary keys are supported. You can mark a property, or properties, as the primary key by applying a KeyAttribute.

Code Listing 20

[Key] public int ProductId { get; set; } |

If we have a composite primary key, we need to use mapping by code. The order of the keys is important so that EF knows which argument refers to which property when an entity is loaded by the Find method.

//composite id[Column(Order = 1)] public int ColumnAId { get; set; } [Column(Order = 2)] public int ColumnBId { get; set; } |

Primary keys can also be decorated with an attribute that tells Entity Framework how keys are to be generated (by the database or manually). This attribute is DatabaseGeneratedAttribute, and its values are explained in further detail in an upcoming section.

Navigation properties

We typically don’t need to include foreign keys in our entities; instead, we use references to the other entity, but we can have them as well. That’s what the ForeignKeyAttribute is for.

Code Listing 22

public Customer Customer { get; set; } [ForeignKey("Customer")] public int CustomerId { get; set; } |

The argument to ForeignKeyAttribute is the name of the navigation property that the foreign key relates to.

Now, suppose we have several relations from one entity to another. For example, a customer might have two collections of projects: one for the current, and another for the past projects. It could be represented in code as this:

Code Listing 23

public class Customer { //the other endpoint will be the CurrentCustomer. [InverseProperty("CurrentCustomer")] public ICollection<Project> CurrentProjects { get; protected set; } //the other endpoint will be the PastCustomer. [InverseProperty("PastCustomer")] public ICollection<Project> PastProjects { get; protected set; } } public class Project { public Customer CurrentCustomer { get; set; } public Customer PastCustomer { get; set; } } |

In this case, it is impossible for EF to figure out which property should be the endpoint for each of these collections, hence the need for the InversePropertyAttribute. When applied to a collection navigation property, it tells Entity Framework the name of the other endpoint’s reference property that will point back to it.

Note: When configuring relationships, you only need to configure one endpoint.

Computed columns

Entity Framework Core does not support implicit mapping to computed columns, which are columns whose values are not physically stored in a table but instead come from SQL formulas. An example of a computed column is combining first and last name into a full name column, which can be achieved in SQL Server very easily. However, you can map computed columns onto properties in your entity explicitly.

Figure 8: Computed columns

Another example of a column that is generated on the database is when we use a trigger for generating its values. You can map server-generated columns to an entity, but you must tell Entity Framework that this property is never to be inserted. For that, we use the DatabaseGeneratedAttribute with the option DatabaseGeneratedOption.Computed.

Code Listing 24

public string FirstName { get; set; }

public string LastName { get; set; }

[DatabaseGenerated(DatabaseGeneratedOption.Computed)] public string FullName { get; protected set; } |

Since the property will never be set, we can have the setter as a protected method, and we mark it as DatabaseGeneratedOption.Computed to let Entity Framework know that it should never try to INSERT or UPDATE this column.

With this approach, you can query the FullName computed property with both LINQ to Objects and LINQ to Entities.

Code Listing 25

//this is executed by the database. var me = ctx.Resources.SingleOrDefault(x => x.FullName == "Ricardo Peres"); //this is executed by the process. var me = ctx.Resources.ToList().SingleOrDefault(x => x.FullName == "Ricardo Peres"); |

In this example, FullName would be a concatenation of the FirstName and the LastName columns, specified as a SQL Server T-SQL expression, so it’s never meant to be inserted or updated.

Computed columns can be one of the following:

- Generated at insert time (ValueGeneratedOnAdd)

- Generated at insert or update time (ValueGeneratedOnAddOrUpdate)

- Never (ValueGeneratedNever)

Limitations

As of the current version of EF, there are some mapping concepts that cannot be achieved with attributes:

- Configuring cascading deletes (see “Cascading”)

- Applying Inheritance patterns (see “Inheritance Strategies”)

- Cascading

- Defining owned entities

- Defining composite primary keys

For these, we need to resort to code configuration, which is explained next.

Mapping by code

Overview

Convenient as attribute mapping may be, it has some drawbacks:

- We need to add references in our domain model to the namespaces and assemblies where the attributes are defined (sometimes called domain pollution).

- We cannot change things dynamically; attributes are statically defined and cannot be changed at runtime.

- There isn’t a centralized location where we can enforce our own conventions.

To help with these limitations, Entity Framework Core offers an additional mapping API: code or fluent mapping. All functionality of the attribute-based mapping is present, and more. Let’s see how we implement the most common scenarios.

Fluent, or code, mapping is configured on an instance of the ModelBuilder class, and normally the place where we can access one is in the OnModelCreating method of the DbContext.

Code Listing 26

public class ProjectsContext : DbContext { protected override void OnModelCreating(ModelBuilder modelBuilder) { //configuration goes here. base.OnModelCreating(modelBuilder); } } |

This infrastructure method is called by Entity Framework when it is initializing a context, after it has automatically mapped the entity classes declared as DbSet<T> collections in the context, as well as entity classes referenced by them.

Schema

Here’s how to configure the entity mappings by code.

Code Listing 27

//set the table and schema. modelBuilder .Entity<Project>() .ToTable("project", "dbo"); //ignoring an entity and all properties of its type. modelBuilder.Ignore<Project>(); |

This is an example of mapping individual properties. Notice how the API allows chaining multiple calls together by having each method return the ModelBuilder instance. In this example, we chain together multiple operations to set the column name, type, maximum length, and required flag. This is very convenient, and arguably makes the code more readable.

Entities

You need to declare a class to be an entity (recognized by EF) if it’s not present in a context collection property.

Code Listing 28

//ignore a property. modelBuilder .Entity<MyClass>() .ToTable("MY_TABLE"); |

Since EF Core 2.0, more than one entity can share the same table (table splitting), with different properties mapped to each of them.

Primary keys

The primary key and the associated generation strategy are set as follows:

Code Listing 29

//setting a property as the key. modelBuilder .Entity<Project>() .HasKey(x => x.ProjectId); //and the generation strategy. modelBuilder .Entity<Project>() .Property(x => x.ProjectId) .UseSqlServerIdentityColumn(); //composite keys modelBuilder .Entity<CustomerManager>() .HasKey(x => new { x.ResourceId, x.CustomerId }); |

Instead of UseSqlServerIdentityColumn, you could instead have ForSqlServerUseSequenceHiLo for using sequences (High-Low algorithm).

Properties

You can configure individual properties in the OnModelCreating method, which includes ignoring them:

Code Listing 30

//ignore a property. modelBuilder .Entity<Project>() .Ignore(x => x.MyUselessProperty); |

Or setting nondefault values:

Code Listing 31

//set the maximum length of a property. modelBuilder .Entity<Project>() .Property(x => x.Name) .HasMaxLength(50); |

Setting a property’s database attributes:

Code Listing 32

//set a property’s values (column name, type, length, nullability). modelBuilder .Entity<Project>() .Property(x => x.Name) .HasColumnName("NAME") .HasColumnType("VARCHAR") .HasMaxLength(50) .IsRequired(); |

Fields

Mapping fields needs to be done using their names and types explicitly:

Code Listing 33

//map a field. modelBuilder .Entity<Project>() .Property<String>("SomeName") .HasField("_someName"); |

Mind you, the visibility of the fields doesn’t matter—even private will work.

Navigation properties

Navigation properties (references and collections) are defined as follows.

Code Listing 34

//a bidirectional many-to-one and its inverse with cascade. modelBuilder .Entity<Project>() .HasOne(x => x.Customer) .WithMany(x => x.Projects) .OnDelete(DeleteBehavior.Cascade); //a bidirectional one-to-many. modelBuilder .Entity<Customer>() .HasMany(x => x.Projects) .WithOne(x => x.Customer) .IsRequired(); //a bidirectional one-to-one-or-zero with cascade. modelBuilder .Entity<Project>() .HasOptional(x => x.Detail) .WithOne(x => x.Project) .IsRequired() .OnDelete(DeleteBehavior.Cascade); //a bidirectional one-to-one (both sides required) with cascade. modelBuilder .Entity<Project>() .HasOne(x => x.Detail) .WithOne(x => x.Project) .IsRequired() .OnDelete(DeleteBehavior.Cascade); //a bidirectional one-to-many with a foreign key property (CustomerId). modelBuilder .Entity<Project>() .HasOne(x => x.Customer) .WithMany(x => x.Projects) .HasForeignKey(x => x.CustomerId); //a bidirectional one-to-many with a non-conventional foreign key column. modelBuilder .Entity<Project>() .HasOne(x => x.Customer) .WithMany(x => x.Projects) .Map(x => x.MapKey("FK_Customer_Id")); |

Note: When configuring relationships, you only need to configure one endpoint.

Computed columns

Not all properties need to come from physical columns. A computed column is one that is generated at the database by a formula (in which case it’s not actually physically stored); it can be specified with the following database generation option:

Code Listing 35

modelBuilder .Entity<Resource>() .Property(x => x.FullName) .ValueGeneratedNever(); |

In this example, FullName would be a concatenation of the FirstName and the LastName columns, specified as a SQL Server T-SQL expression, so it’s never meant to be inserted or updated.

Computed columns can be one of the following:

- Generated at insert time (ValueGeneratedOnAdd).

- Generated at insert or update time (ValueGeneratedOnAddOrUpdate).

- Never (ValueGeneratedNever).

Default values

It’s also possible to specify the default value for a column to be used when a new record is inserted:

Code Listing 36

modelBuilder .Entity<Resource>() .Property(x => x.FullName) .ForSqlServerHasDefaultValueSql("SomeFunction()"); |

Here, SomeFunction will be included in the CREATE TABLE statement if the database is created by Entity Framework. This configuration cannot be done using attributes.

Global Filters

In version 2.0, a very handy feature was introduced: global filters. Global filters are useful in a couple of scenarios, such as:

- Multi-tenant code: if we have a column that contains the identifier for the current tenant, we can filter by it automatically.

- Soft-deletes: instead of deleting records, we mark them as deleted, and filter them out automatically.

Global filters are defined in the OnModelCreating method, and its configuration is done like this:

Code Listing 37

protected override void OnModelCreating(ModelBuilder modelBuilder) { modelBuilder .Entity<Project>() .HasQueryFilter(x => x.IsDeleted == false); base.OnModelCreating(builder); } |

Here we are saying that entities of type Project, whether loaded in a query or from a collection (one-to-many), are automatically filtered by the value in its IsDeleted property. Two exceptions:

- When an entity is loaded explicitly by its id (Find).

- When a one-to-one or many-to-one related entity is loaded.

You can have an arbitrary condition in the filter clause, as long as it can be executed by LINQ. For multi-tenant code, you would have something like this instead:

Code Listing 38

public string TenantId { get; set; } protected override void OnModelCreating(ModelBuilder builder) { builder .Entity<Project>() .HasQueryFilter(x => x.TenantId == this.TenantId); base.OnModelCreating(builder); } |

Self-contained configuration

New in EF Core 2 is the possibility of having configuration classes for storing the code configuration for an entity; it’s a good way to have your code organized. You need to inherit from IEntityTypeConfiguration<T> and add your mapping code there:

Code Listing 39

public class ProjectEntityTypeConfiguration : IEntityTypeConfiguration<Project> { public void Configure(EntityTypeBuilder<Project> builder) { builder .HasOne(x => x.Customer) .WithMany(x => x.Projects) .OnDelete(DeleteBehavior.Cascade); } } |

But these are not loaded automatically, so you need to do so explicitly:

Code Listing 40

protected override void OnModelCreating(ModelBuilder modelBuilder) { modelBuilder.ApplyConfiguration(new ProjectEntityTypeConfiguration()); } |

Identifier strategies

Overview

Entity Framework requires that all entities have an identifier property that will map to the table’s primary key. If this primary key is composite, multiple properties can be collectively designated as the identifier.

Identity

Although Entity Framework is not tied to any specific database engine, out of the box it works better with SQL Server. Specifically, it knows how to work with IDENTITY columns, arguably the most common way in the SQL Server world to generate primary keys. Until recently, it was not supported by some major database engines, such as Oracle.

By convention, whenever Entity Framework encounters a primary key of an integer type (Int32 or Int64), it will assume that it is an IDENTITY column. When generating the database, it will start with value 1 and use the increase step of 1. It is not possible to change these parameters.

Tip: Although similar concepts exist in other database engines, Entity Framework can only use IDENTITY with SQL Server out of the box.

Manually generated primary keys

In the event that the identifier value is not automatically generated by the database, it must be manually set for each entity to be saved. If it is Int32 or Int64, and you want to use attributes for the mapping, then mark the identifier property with a DatabaseGeneratedAttribute and pass it the DatabaseGeneratedOption.None. This will avoid the built-in convention that will assume IDENTITY.

Code Listing 41

[Key] [DatabaseGenerated(DatabaseGeneratedOption.None)] public int ProjectId { get; set; } |

Use the following if you prefer fluent mapping.

Code Listing 42

protected override void OnModelCreating(ModelBuilder modelBuilder) { modelBuilder .Entity<Project>() .HasKey(x => x.ProjectId); modelBuilder .Property(x => x.ProjectId) .ValueGeneratedNever();

base.OnModelCreating(modelBuilder); } |

In this case, it is your responsibility to assign a valid identifier that doesn’t already exist in the database. This is quite complex, mostly because of concurrent accesses and transactions. A popular alternative consists of using a Guid for the primary key column. You still have to initialize its value yourself, but the generation algorithm ensures that there won’t ever be two identical values.

Code Listing 43

public Project() { //always set the ID for every new instance of a Project. ProjectId = Guid.NewGuid(); } [Key] [DatabaseGenerated(DatabaseGeneratedOption.None)] public Guid ProjectId { get; set; } |

Note: When using non-integral identifier properties, the default is not to have them generated by the database, so you can safely skip the DatabaseGeneratedAttribute.

Note: Another benefit of using Guids for primary keys is that you can merge records from different databases into the same table; the records will never have conflicting keys.

High-Low

Another very popular identifier generation strategy is High-Low (or Hi-Lo). This one is very useful when we want the client to know beforehand what the identifier will be, while avoiding collisions. Here’s a simple algorithm for it:

- Upon start, or when the need first arises, the ORM asks the database for a next range of values—the High part—which is then reserved.

- The ORM has either configured a number of Lows to use, or it will continue generating new ones until it exhausts the numbers available (reaches maximum number capacity).

- When the ORM has to insert a number, it combines the High part—which was reserved for this instance—with the next Low. The ORM knows what the last one was, and just adds 1 to it.

- When all the Lows are exhausted, the ORM goes to the database and reserves another High value.

There are many ways in which this algorithm can be implemented, but, somewhat sadly, it uses sequences for storing the current High values. What this means is that it can only be used with SQL Server 2012 or higher, which, granted, is probably not a big problem nowadays.

This is the way to configure sequences for primary key generation:

Code Listing 44

modelBuilder .Entity<Resource>() .Property(x => x.FullName) .ForSqlServerUseSequenceHiLo("sequencename"); |

Note: The sequence specified is set on the property, not the primary key, although the property should be the primary key.

Note: The sequence name is optional; it is used when you want to specify different sequences per entity.

Tip: Sequences for primary key generation cannot be specified by attributes; you need to use the fluent API.

Inheritance

Consider the following class hierarchy.

Figure 9: An Inheritance model

In this example, we have an abstract concept, Tool, and three concrete representations of it: DevelopmentTool, TestingTool, and ManagementTool. Each Tool must be one of these types.

In object-oriented languages, we have class inheritance, which is something relational databases don’t natively support. How can we store this in a relational database?

Martin Fowler, in his seminal work Patterns of Enterprise Application Architecture, described three patterns for persisting class hierarchies in relational databases:

- Single Table Inheritance or Table Per Class Hierarchy: A single table is used to represent the entire hierarchy; it contains columns for all mapped properties of all classes. Many of these will be NULL because they will only exist for one particular class; one discriminating column will store a value that will tell Entity Framework which class a particular record will map to.

Figure 10: Single Table Inheritance data model

- Class Table Inheritance or Table Per Class: A table will be used for the columns for all mapped base-class properties, and additional tables will exist for all concrete classes; the additional tables will be linked by foreign keys to the base table.

Figure 11: Class Table Inheritance data model

- Concrete Table Inheritance or Table Per Concrete Class: One table is used for each concrete class, each with columns for all mapped properties, either specific or inherited by each class.

Figure 12: Concrete Table Inheritance data model

You can see a more detailed explanation of these patterns on Martin’s website. For now, I’ll leave you with some thoughts:

- Single Table Inheritance, when it comes to querying from a base class, offers the fastest performance because all information is contained in a single table. However, if you have lots of properties in all of the classes, it will be a difficult read, and you will have many “nullable” columns. In all of the concrete classes, all properties must be optional because they must allow null values. This is because different entities will be stored in the same class, and not all share the same columns.

- Class Table Inheritance offers a good balance between table tidiness and performance. When querying a base class, a LEFT JOIN will be required to join each table from derived classes to the base class table. A record will exist in the base class table and in exactly one of the derived class tables.

- Concrete Table Inheritance for a query for a base class requires several UNIONs, one for each table of each derived class, because Entity Framework does not know beforehand in which table to look. This means that you cannot use IDENTITY as the identifier generation pattern or any one that might generate identical values for any two tables. Entity Framework would be confused if it found two records with the same ID. Also, you will have the same columns—those from the base class, duplicated on all tables.

As far as Entity Framework is concerned, there really isn’t any difference; classes are naturally polymorphic. However, Entity Framework Core 1.1 only supports the Single Table Inheritance pattern. See 0 to find out how we can perform queries on class hierarchies. Here’s how we can apply Single Table Inheritance:

Code Listing 45

public abstract class Tool { public string Name { get; set; }

public int ToolId { get; set; } } public class DevelopmentTool : Tool { //String is inherently nullable. public string Language { get; set; } } public class ManagementTool : Tool { //nullable Boolean public bool? CompatibleWithProject { get; set; } } public class TestingTool : Tool { //nullable Boolean public bool? Automated { get; set; } } |

As you can see, there’s nothing special you need to do. Single table inheritance is the default strategy. One important thing, though: because all properties of each derived class will be stored in the same table, all of them need to be nullable. It’s easy to understand why. Each record in the table will potentially correspond to any of the derived classes, and their specific properties only have meaning to them, not to the others, so they may be undefined (NULL). In this example, I have declared all properties in the derived classes as nullable. Notice that I am not mapping the discriminator column here (for the Single Table Inheritance pattern); it belongs to the database only.

Some notes:

- All properties in derived classes need to be marked as nullable, because all of them will be stored in the same table, and may not exist for all concrete classes.

- The Single Table Inheritance pattern will be applied by convention; there’s no need to explicitly state it.

- Other inheritance mapping patterns will come in the next versions of Entity Framework Core.

Conventions

The current version of Entity Framework Core at the time this book was written (1.1) comes with a number of conventions. Conventions dictate how EF will configure some aspects of your model when they are not explicitly defined.

The built-in conventions are:

- All types exposed from a DbSet<T> collection in the DbContext-derived class with public getters are mapped automatically.

- All classes that appear in DbSet<T> properties on a DbContext-derived class are mapped to a table with the name of the property.

- All types for which there is no DbSet<T> property will be mapped to tables with the name of the class.

- All public properties of all mapped types with a getter and a setter are mapped automatically, unless explicitly excluded.

- All properties of nullable types are not required; those from non-nullable types (value types in .NET) are required.

- Single primary keys of integer types will use IDENTITY as the generation strategy.

- Associations to other entities are discovered automatically, and the foreign key columns are built by composing the foreign entity name and its primary key.

- Child entities are deleted from the database whenever their parent is, if the relation is set to required.

For now, there is no easy way to add our own custom conventions or disable existing ones, which is rather annoying, but will improve in future versions. You can, however, implement your own mechanism by building an API that configures values in the ModelBuilder instance. In this case, you should plug this API in the OnModelCreating virtual method.

And, of course, we can always override the conventional table and column names using attributes.

Code Listing 46

//change the physical table name. [Table("MY_PROJECT")] public class Project { //change the physical column name. [Column("ID")] public int ProjectId { get; set; } } |

Generating entities automatically

One thing often requested is the ability to generate entity types that Entity Framework Core can use straightaway. This normally occurs when we have an existing, large database with many tables for which it would be time consuming to create the classes manually. This is not exactly the purpose of the Code First approach, but we have that option. You should be thankful that we do—imagine how it would be if you had to generate hundreds of classes by hand.

In order to generate your classes, you need to run the following command:

dotnet ef dbcontext scaffold “Data Source=.\SQLEXPRESS; Initial Catalog=Succinctly; Integrated Security=SSPI” Microsoft.EntityFrameworkCore.SqlServer

Note: Make sure to replace the connection string with one that is specific to your system.

After executing this command, Entity Framework will generate classes for all the tables in your database that have a primary key defined. Because these are generated as partial classes, you can easily extend them without the risk of losing your changes in the next generation.

- 1800+ high-performance UI components.

- Includes popular controls such as Grid, Chart, Scheduler, and more.

- 24x5 unlimited support by developers.