CHAPTER 2

A Closer Look at C# 12

C# 12 has brought with it a host of new features. With the pace at which C# is progressing, it remains a challenge for developers to stay up to date. The new features of C# 12 include:

- Primary constructors

- Collection expressions

- Ref readonly parameters

- Default Lambda parameters

- Alias any type

- Inline arrays

- Experimental attribute

- Interceptors

While developers might feel the pressure of staying up to date with everything that is new with every release of .NET and C#, I have come to a different conclusion. Instead of seeing it as a five-course meal that needs to be worked through in a single sitting, I am approaching all these new features in each new release like a buffet table.

A smorgasbord of C# and .NET features presented as a grand spread, meticulously prepared by Microsoft to satisfy the eclectic tastes of the most discerning code connoisseurs.

“Yes, thank you very much,” I murmur as I slowly pace along the buffet with my dinner plate, perusing all that is on display.

As I saunter along the buffet table (taking care not to walk too fast), my plate ready for the taking, I whisper to myself: “A little bit of record structs, a dash of global using directives, a slice of file-scoped namespaces, topped with some file-scoped types… Oohh, primary constructors and collection expressions, haven’t tried you before!”

I carefully scoop just enough onto my plate of each so that I don’t look greedy. You see, the trick to navigating any buffet table is to put something on your plate, but also to pop something surreptitiously into your mouth (from your plate, not directly from the table) while standing at the table. This way, you get to taste more while only returning to your table with a modest plate of food. The same can be said for the flurry of new features with every release of .NET.

You don’t have to learn to implement every new feature in every release of .NET in every project you create. What you do have to do, however, is peruse the buffet table. You must walk up to it, pick something up here, nibble something there, and return to your table with a manageable plate of food. While this metaphor does well to illustrate how I can grow my skills as a developer, and when life imitates art, grow my waistline as a buffet table peruser, it does not account for the challenges developers face in the real world. Trying to grow as a developer while managing a healthy work-life balance is challenging when you try to do it all at once. But it starts with showing up and taking little (pun intended), bite-sized nibbles.

As Carl Orff’s “O Fortuna” from Carmina Burana starts playing in our minds, the waiters, ready with the champagne, join me as we walk up to the buffet table to see what’s on display.

Primary constructors

I’m not convinced I like primary constructors. My mind isn’t yet made up. In fact, it feels like it goes against my flow of writing code. Let me show you what I mean.

Code Listing 29 illustrates a weather service that generates totally random weather conditions for random locations every time you call it.

Code Listing 29: The LyingWeatherController

using Microsoft.AspNetCore.Mvc; using PrimaryConstructorsDemo.Services; namespace PrimaryConstructorsDemo.Controllers; [ApiController] [Route("[controller]")] public class LyingWeatherForecastController : ControllerBase { private readonly IRandomCityService _randomCityService; private readonly IRandomSummaryService _randomSummaryService; public LyingWeatherForecastController(IRandomCityService randomCityService, IRandomSummaryService randomSummaryService) { _randomCityService = randomCityService; _randomSummaryService = randomSummaryService; } [HttpGet(Name = "GetWeatherForecast")] public IEnumerable<WeatherForecast> Get() { return Enumerable.Range(1, 5).Select(index => new WeatherForecast { CityName = _randomCityService.GetRandomCity(), Date = DateOnly.FromDateTime(DateTime.Now.AddDays(index)), TemperatureC = Random.Shared.Next(-20, 55), Summary = _randomSummaryService.GetRandomSummary() }) .ToArray(); } } |

It happens to be correct about 1 percent of the time. Nevertheless, I like this method of creating classes. I have a constructor, I inject some services, I set those to private fields, and I use the services in my class. End of story.

Let’s take a look at the same class using primary constructors. The parameters on the constructor are moved up to the class level. Now I can remove my constructor totally, as well as the private fields, and use the injected services in my code.

Code Listing 30: Using Primary Constructors

using Microsoft.AspNetCore.Mvc; using PrimaryConstructorsDemo.Services; namespace PrimaryConstructorsDemo.Controllers; [ApiController] [Route("[controller]")] public class LyingWeatherForecastController( IRandomCityService randomCityService, IRandomSummaryService randomSummaryService) : ControllerBase {

[HttpGet(Name = "GetWeatherForecast")] public IEnumerable<WeatherForecast> Get() { return Enumerable.Range(1, 5).Select(index => new WeatherForecast { CityName = randomCityService.GetRandomCity(), Date = DateOnly.FromDateTime(DateTime.Now.AddDays(index)), TemperatureC = Random.Shared.Next(-20, 55), Summary = randomSummaryService.GetRandomSummary() }) .ToArray(); } } |

This resulting code takes some getting used to, that’s for sure.

What the compiler sees

Let’s simplify the code and see what the lowered C# looks like. Code Listing 31 illustrates a simplified LyingWeatherForecastController class.

Code Listing 31: The Simplified Class

public class LyingWeatherForecastController( IRandomCityService randomCityService, IRandomSummaryService randomSummaryService) : IWidget { public string GetSomeWeatherData() { var city = randomCityService.GetRandomCity(); var summary = randomSummaryService.GetRandomSummary(); return $"It is {summary} in {city}"; } } |

Have a look what the lowered C# code looks like in Code Listing 32. Notice that the private fields for IRandomCityService and IRandomSummaryService are not readonly.

Code Listing 32: The Lowered C# Code

public class LyingWeatherForecastController : IWidget { [CompilerGenerated] [DebuggerBrowsable(DebuggerBrowsableState.Never)] private IRandomCityService <randomCityService>P; [CompilerGenerated] [DebuggerBrowsable(DebuggerBrowsableState.Never)] private IRandomSummaryService <randomSummaryService>P; public LyingWeatherForecastController(IRandomCityService randomCityService, IRandomSummaryService randomSummaryService) { <randomCityService>P = randomCityService; <randomSummaryService>P = randomSummaryService; base..ctor(); } public string GetSomeWeatherData() { string randomCity = <randomCityService>P.GetRandomCity(); string randomSummary = <randomSummaryService>P.GetRandomSummary(); return string.Concat("It is ", randomSummary, " in ", randomCity); } } |

It is, therefore, possible to change the value of these fields from inside the class—so watch out for that little pitfall.

Collection expressions

I have to say that I do like collection expressions. In my opinion, it weeds out a little bit of the unnecessary fluff. Of course, the argument can be made that it’s not as expressive, but here we are. Let’s look at an example.

Code Listing 33: A Simple Array

int[] scores = new int[] { 97, 92, 81, 60 }; |

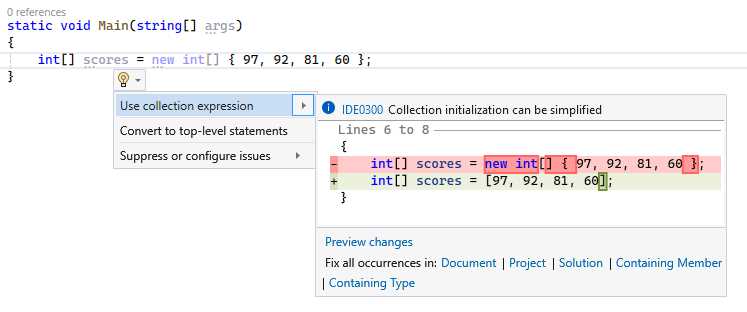

As seen in Code Listing 33, we have a stock standard array of integers. Visual Studio, however, will suggest a quick action to use collection expressions, as seen in Figure 22.

Figure 22: Refactoring Quick Action

You can see the resulting code in Code Listing 34.

Code Listing 34: The Collection Expression

int[] scores = [97, 92, 81, 60]; |

Just also note that you can’t use var with collection expressions, as then there is no target type. Collection expressions also apply to Span<T>, as seen in Code Listing 35.

Code Listing 35: Span Collection Expression

Span<int> foo = ['a', 'b', 'c']; |

Collection expressions may appeal to some developers but not to others. With C# 12, you have the option to use collection expressions if you choose to.

Ref readonly parameters

Ref readonly parameters are now a thing in C# 12. Consider the code in Code Listing 36. This simply passes a score to the Increment method of the Counter class and then prints out the score.

Code Listing 36: Arbitrary Code Example

var score = 30; var c = new Counter(); c.Increment(score); Console.WriteLine($"The score is {score}"); public class Counter { public void Increment(int score) { score++; } } |

As you would expect, the value of score remains unchanged. Why is this the case? Well, the score parameter is passed by value. In other words, a copy of the variable is made, and the method acts on this copy. Therefore, changes to this copy inside the method will not affect the original variable.

Tip: Value types are copied by default.

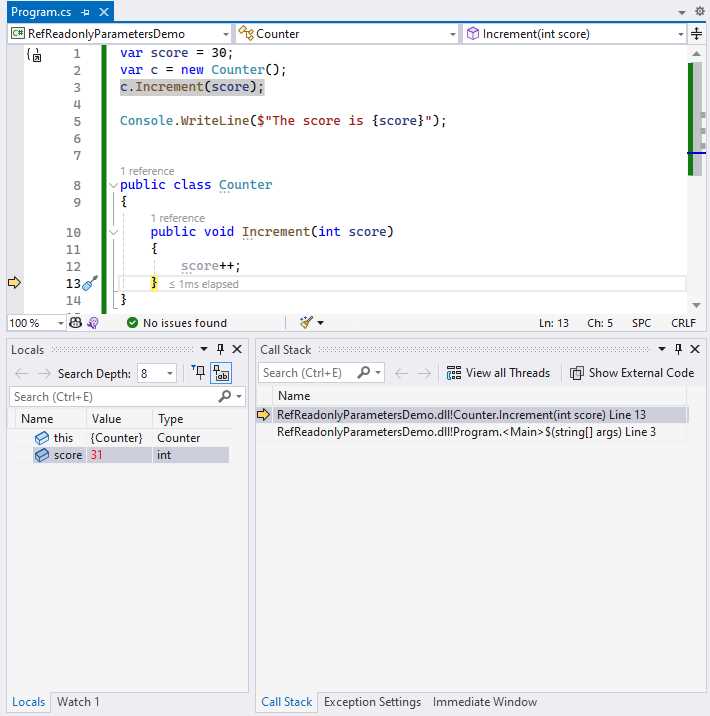

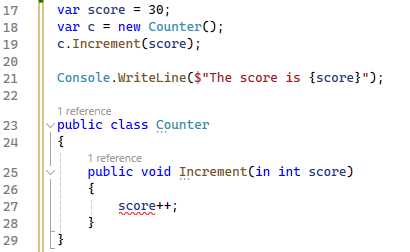

We can see this behavior when we inspect the call stack, as seen in Figure 23.

Figure 23: Value of score Variable Inside Increment

When the code execution reaches the Increment method and increments the score parameter, the value changes to 31. As seen in Figure 24, a whole different story is at play in the calling code.

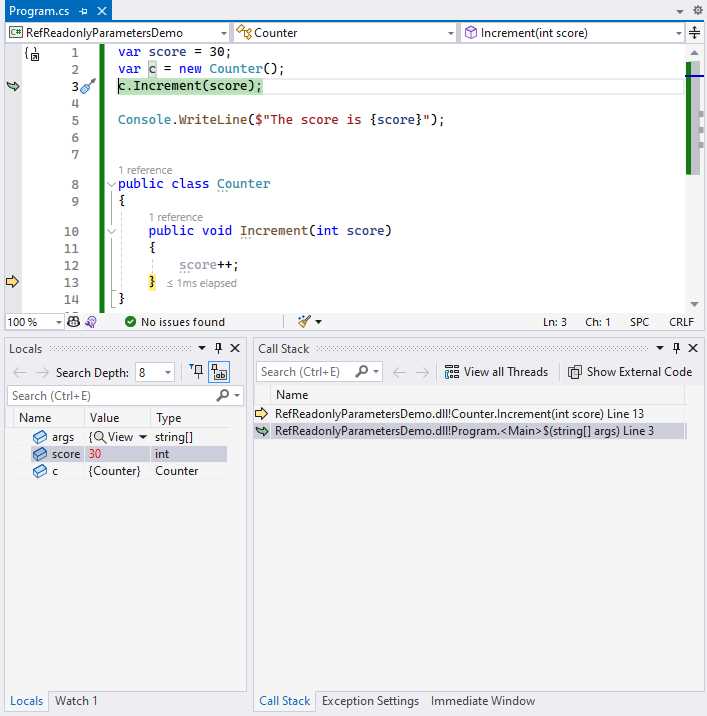

Figure 24: Value of score Variable in Main

The score variable’s value in the calling code remains unchanged at 30. This is because, as mentioned previously, the increment acted on a copy of this variable.

In order to change this behavior, we can add the ref keyword to the parameter and the calling code, as seen in Code Listing 37. This allows me to pass down the reference to the score variable instead of the value of the score variable.

Code Listing 37: Arbitrary Code Example Using Ref readonly Parameters

var score = 30; var c = new Counter(); c.Increment(ref score); Console.WriteLine($"The score is {score}"); public class Counter { public void Increment(ref int score) { score++; } } |

What does this do to our variable, you might wonder.

As soon as the variable is incremented, I am increasing the reference of the variable score, not the value itself. This means that we will see this effect outside the Increment method in the calling code.

Figure 25: Value of score Variable Inside Increment

Figure 25 illustrates this point when looking at the call stack again. As soon as the score parameter is incremented, the value increases to 31, as expected. The difference now, because we used the ref keyword, is that the original variable in the calling code has also increased, as seen in Figure 26.

Figure 26: Value of score Variable in Main

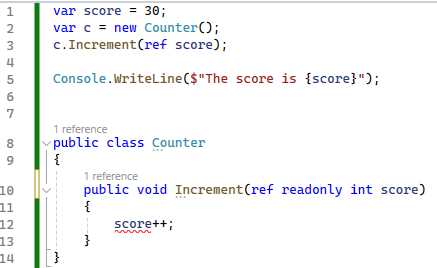

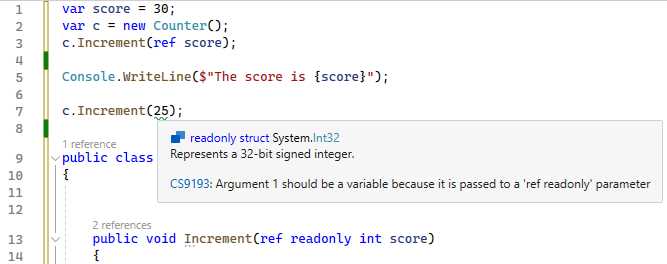

With C# 12, however, you can add the readonly keyword, as seen in Figure 27.

Figure 27: Using Ref readonly

Using the ref readonly keywords in the Increment method will result in a compilation error telling you that the reference passed is read-only, and that you can’t change it. Now you might be wondering, why not just use the in keyword, and why do we have ref readonly to begin with?

Code Listing 38: Using the in Keyword

public void Increment(in int score) { score++; } |

Code Listing 38 illustrates the use of the in keyword. Looking at Figure 28, you will see that this also results in a compilation error.

Figure 28: The Result Is the Same Compilation Error

So then, why add another feature to C# 12 that does the same thing introduced in C# 7.2 with the in keyword?

Note: You can read about the release of C# 7.2 here.

To explain the reason, we first need to understand the difference between an rvalue and an lvalue.

Rvalue stands for right-hand side value and refers to the value that appears on the right side of an assignment expression. In other words, it is a value that does not have a persistent memory location.

Lvalue, on the other hand, stands for left-hand side and appears on the left-hand side of an assignment expression. In other words, an lvalue typically represents a variable or object that can be assigned a new value.

Looking at the expression int x = 27; and applying the definitions for an lvalue and an rvalue, 27 is an rvalue, while x is an lvalue.

To put it simply, using ref readonly offers additional guarantees by warning that an rvalue (in other words, not a variable) is being passed. This enhances clarity and intent at the call site that a reference is being captured.

Figure 29: Warning on rvalue

By introducing the ref readonly feature in C# 12, you can enforce this indication that a reference is being captured, and that the argument passed is a temporary value instead of a variable that exists beyond the method call (as seen in Figure 29).

Default lambda parameters

Before default lambda parameters, we had to invoke the lambda by specifying the value for personToGreet, as seen in Code Listing 39.

Code Listing 39: Before Default Lambda Parameters

var greeting = (string personToGreet) => $"Hello, {personToGreet}!"; Console.WriteLine(greeting("John")); // Hello, John! |

In C# 12, however, we can now set a default value for personToGreet, as seen in Code Listing 40.

Code Listing 40: Using Default Lambda Parameters

var greeting = (string personToGreet = "World") => $"Hello, {personToGreet}!"; Console.WriteLine(greeting()); // Hello, World! |

This is a small, but welcome change.

Alias any type

In a nutshell, this feature is relaxing the rules on where the using alias directive can be used. In other words, you can now create semantic aliases for tuple types, array types, and pointer types where in the past, you could not. Previously, you could only alias named types, as seen in Code Listing 41.

Code Listing 41: Using Alias on Named Types

using Employee = System.Collections.Generic.Dictionary<string, string>; using Foo = System.Console; Employee employee = new() { { "Name", "John Doe" } }; Foo.WriteLine(employee["Name"]); Foo.ReadLine(); |

With C# 12, however, you can now create an alias for a type that isn’t a named type. You can create a using alias for a tuple, as seen in Code Listing 42.

Code Listing 42: Using Alias on a Tuple

using TuplePoints = (int x, int y); using Foo = System.Console; TuplePoints p = (3, 4); Foo.WriteLine(p.x); Foo.WriteLine(p.y); Foo.ReadLine(); |

Being able to alias any type is useful because it reduces the amount of code you need to write, making your code more readable.

Experimental attribute

Library authors will most likely make use of the Experimental attribute the most. I’m not so sure that this can be classified as a feature in C# 12, but it’s here, so let’s have a look at it.

Code Listing 43: Using the Experimental Attribute

using System.Diagnostics.CodeAnalysis; var person = new Person { Name = "John" }; var age = person.GetAge(1980); var guid = Guid.NewGuid(); var age2 = person.GetAge(guid); Console.WriteLine(age); public class Person { public string Name { get; set; }

public int GetAge(int yearBorn) { // Do some standard calculation. // Just return default for now. return default; } [Experimental("fef6b55e36f753c893f5afe8435bcca1" , UrlFormat = "https://gist.github.com/dirkstrauss/{0}")] public int GetAge(Guid guid) { // Do advanced experimental calculation. // Just return default for now. return default; } } |

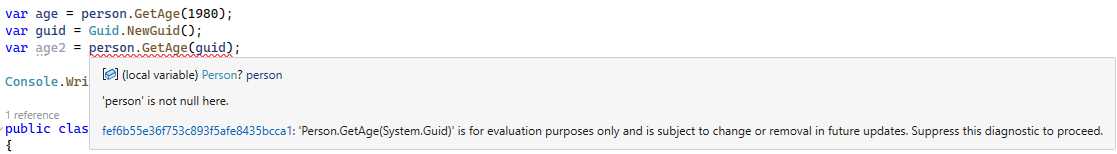

Code Listing 43 shows some boilerplate code for a class called Person that has two GetAge methods. The first method is one that is safe to use, but I have included another experimental method that is slightly risky to use.

The Experimental attribute allows me to decorate my second GetAge method and give it a diagnostic ID that the compiler can use to report any use of my method. It also allows me to set a URL for the corresponding documentation.

Figure 30: The Error Message Displayed in Visual Studio

As seen in Figure 30, if I try to use this experimental feature, Visual Studio will display this warning to me, allowing me to click on the diagnostic ID that will take me to the relevant documentation for this warning. I have used a GUID, but you might be used to seeing these as compiler warnings in Visual Studio starting with “CS.”

Note: You can take a look at some examples of these compiler warnings here.

In order for me to use this experimental feature, I need to explicitly suppress the warning in my code, as seen in Code Listing 44.

Code Listing 44: Suppressing the Warning

|

#pragma warning disable fef6b55e36f753c893f5afe8435bcca1 // Type is for evaluation purposes only and is subject to change or removal in future updates. Suppress this diagnostic to proceed. var age2 = person.GetAge(guid); #pragma warning restore fef6b55e36f753c893f5afe8435bcca1 // Type is for evaluation purposes only and is subject to change or removal in future updates. Suppress this diagnostic to proceed. |

I can also use the <NoWarn> csproj property to suppress this warning, as seen in Code Listing 45.

Code Listing 45: Using the <NoWarn> csproj Property

<Project Sdk="Microsoft.NET.Sdk"> <PropertyGroup> <OutputType>Exe</OutputType> <TargetFramework>net8.0</TargetFramework> <ImplicitUsings>enable</ImplicitUsings> <Nullable>enable</Nullable> <NoWarn>fef6b55e36f753c893f5afe8435bcca1</NoWarn> </PropertyGroup> </Project> |

Personally, I dislike the #pragma warning directive in code, but it provides a lot of visibility and expressiveness in the fact that you are suppressing a compiler warning. I would rather use the #pragma warning directive (even though I dislike it) as opposed to the <NoWarn> property in the csproj file. I feel that it’s almost too hidden away in the csproj file.

There is an Afrikaans saying “Stille waters, diepe grond, onder draai die duiwel rond,” which translates to “Still waters run deep, and that is where the devil lurks.”

The devil in this detail is the <NoWarn> property in the csproj file suppressing a warning in the code editor that you spend most of your time in. If I have suppressed a warning, I want to know about it—and more importantly, I want other developers who contribute to my code to know about it, too.

Interceptors

One of the most exciting and fun features in C# 12 has got to be interceptors. Microsoft warns that interceptors are experimental and only available in preview mode with C# 12, and that this feature may be subject to breaking changes or removal in a future release.

It goes without saying that you are not encouraged to use this in production. There, I’ve said it. With that out of the way, let’s give it a whirl.

You will see in Code Listing 46 that I have a class called ArraySorter with a horribly inefficient Sort method.

Tip: Do not use this Sort method in your code… ever.

This is basically a bubble sort, but it is not high-performance when having to sort large arrays.

Code Listing 46: The Old ArraySorter Class

namespace InterceptorDemo; public class ArraySorter { public void Sort(int[] array) { Console.WriteLine($"Sorting array using Bubble Sort to sort {array.Length} elements");

bool swapped; do { swapped = false; for (int i = 0; i < array.Length - 1; i++) { if (array[i] > array[i + 1]) { int temp = array[i + 1]; array[i + 1] = array[i]; array[i] = temp; swapped = true; } } } while (swapped); } } |

In my Program.cs file, seen in Code Listing 47, I am creating an array of random integers.

Code Listing 47: The Program.cs Class

using System.Diagnostics; using InterceptorDemo; var random = new Random(); var largeArray = Enumerable.Range(0, 50000).Select(x => random.Next()).ToArray(); var sorter = new ArraySorter(); var stopwatch = Stopwatch.StartNew(); sorter.Sort(largeArray); stopwatch.Stop(); Console.WriteLine($"Time taken: {stopwatch.ElapsedMilliseconds} ms"); Console.ReadLine(); |

I then instantiate my ArraySorter class and call the Sort method, passing it the largeArray variable.

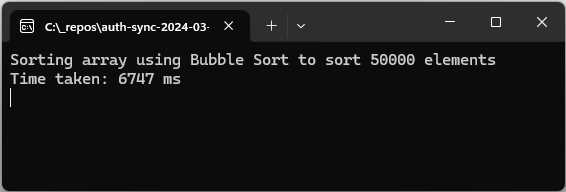

Figure 31: The Bubble Sort Results

The results of the current Sort method are displayed in Figure 31.

Tip: Do not increase the size of the largeArray beyond 50,000 and run the bubble sort—you’ll be here forever and a day.

What I want to do is hijack this inefficient Sort method. I want to implement a coup d'état and overthrow the bubble sort. And I want to do this without changing the calling code—otherwise, I couldn’t call this an “interceptor” at all.

Code Listing 48: The csproj File

<Project Sdk="Microsoft.NET.Sdk"> <PropertyGroup> <OutputType>Exe</OutputType> <TargetFramework>net8.0</TargetFramework> <ImplicitUsings>enable</ImplicitUsings> <Nullable>enable</Nullable> <InterceptorsPreviewNamespaces>$(InterceptorsPreviewNamespaces);InterceptorDemo</InterceptorsPreviewNamespaces> </PropertyGroup> </Project> |

To start off, I need to modify the csproj file and opt in to use the experimental interceptors feature. Let’s add the property <InterceptorsPreviewNamespaces> and include our InterceptorDemo namespace in here.

Next, we need to add the InterceptsLocationAttribute, which is crucial for implementing interceptors, as this is not yet available in our build of C# 12. You can see this in Code Listing 49. Put simply, this allows us to use the interceptor feature.

Code Listing 49: The InterceptsLocationAttribute Helper Class

namespace System.Runtime.CompilerServices { [AttributeUsage(AttributeTargets.Method, AllowMultiple = false)] internal sealed class InterceptsLocationAttribute : Attribute { public InterceptsLocationAttribute(string filePath, int line, int column) { } } } |

I then create a class called Inception, as seen in Code Listing 50.

Code Listing 50: Our Interceptor

using System.Runtime.CompilerServices; namespace InterceptorDemo; public static class Inception { [InterceptsLocation( filePath: "C:\\_repos\\InterceptorDemo\\Program.cs", line: 11, column: 8)] public static void InterceptSort( this ArraySorter arraySorter, int[] array) { Console.WriteLine($"Intercept using Array.Sort to sort {array.Length} elements"); Array.Sort(array); } } |

You need to tell the interceptor exactly what method to intercept. Let’s break this down. We have the following moving parts in our static InterceptSort method:

- filePath: The path to your Program.cs file.

- line: The line in your Program.cs file where sorter.Sort(largeArray) is found.

- column: The column number of the start of the Sort method in the Program.cs file.

- this ArraySorter arraySorter: The InterceptSort method is an extension method, so we need to tell it which class to act on (which class we need to intercept)

- int[] array: Tells our InterceptSort method that we are passing an array of integers.

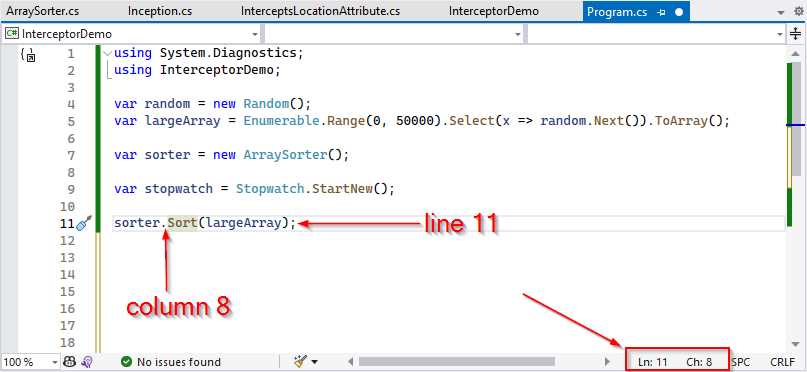

To clarify the line and column values, have a look at Figure 32.

Figure 32: Finding the Line and Column Values

These values can also be found in the bottom-right corner of your editor window in Visual Studio when you place your cursor at the start of the Sort method.

Note: It goes without saying that the values you will have for your InterceptSort method for line and column will differ from mine in the code example in Code Listing 50.

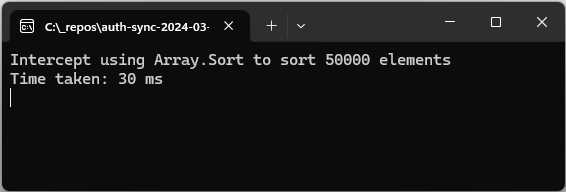

You are now ready to run your application. Give it a whirl and look at the console window seen in Figure 33.

Figure 33: The Sort Method Intercepted

The interceptor jumps into action and grabs the call to the Sort method, allowing our code to use a more efficient way to sort our array of integers.

For fun, try changing up the number of elements in our array of integers and running the intercepted Sort method. Interceptors are really great to work with when thinking about code generators, but how much use they will be to the wider developer community remains to be seen. That is, if interceptors make it out of the experimental phase.

In conclusion

This chapter took us through a buffet of new features introduced in C# 12. One feature that I didn’t cover was inline arrays. This is because it is more aimed at the runtime team at Microsoft and library authors. You can read more about inline arrays here.

It is a very niche use case that I didn’t think would benefit the larger audience of this book. It’s like finding a tub of tofu on the buffet table. Some folks will pick at it, while others won’t. Invariably, you will find it largely untouched after the party is over. If I erred in omitting this feature in the book, I apologize. Perhaps it’s just me that doesn’t like tofu.

That being said, C# 12 brings with it some really interesting features and gives me the feeling that C# 13 might build on some of these in the next release.

In the next chapter, we will have a look at some more new features in .NET 8.

- 1800+ high-performance UI components.

- Includes popular controls such as Grid, Chart, Scheduler, and more.

- 24x5 unlimited support by developers.