CHAPTER 4

Performance Improvements

The performance well has by no means run dry. Even though .NET 6 was fast, and one could imagine that there was little else to do to speed up .NET any more, along comes .NET 7, with some serious performance improvements. To quantify just how many performance improvements there are, we need to refer back to an article Stephen Toub (a developer on the .NET team at Microsoft) wrote in August of 2022.

Each time he reviewed a PR that might positively impact performance, he copied that link to a journal. When he reviewed the journal for the article, he discovered that almost a thousand performance-impacting pull requests went into the release of .NET 7.

We can safely assume that .NET 7 is very fast. Let’s look at just how fast it is in the following sections.

Benchmarking .NET 6 vs. .NET 7

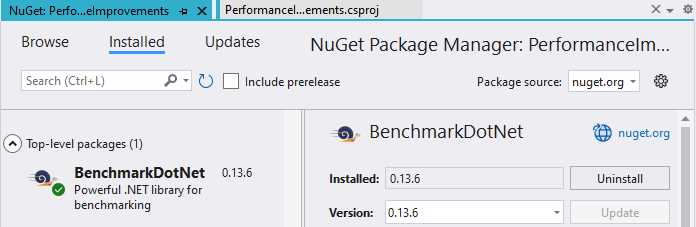

Illustrating the performance improvements in .NET 7, we need to look at setting up a simple Console application that includes the NuGet package BenchmarkDotNet, as seen in Figure 40.

Figure 40: BenchmarkDotNet

To compare the improvements in .NET 7, we benchmark it against .NET 6 to illustrate how the same code performs across both .NET versions. We must therefore target multiple frameworks in our Console application.

The easiest way to do this is to modify the csproj file of the Console application used for benchmarking.

You can see how my csproj file looks in Code Listing 64.

Code Listing 64: The csproj File Targeting .NET 6 and .NET 7

<Project Sdk="Microsoft.NET.Sdk"> <PropertyGroup> <OutputType>Exe</OutputType> <TargetFrameworks>net7.0;net6.0</TargetFrameworks> <ImplicitUsings>enable</ImplicitUsings> <Nullable>enable</Nullable> </PropertyGroup> <ItemGroup> <PackageReference Include="benchmarkdotnet" Version="0.13.6" /> </ItemGroup> </Project> |

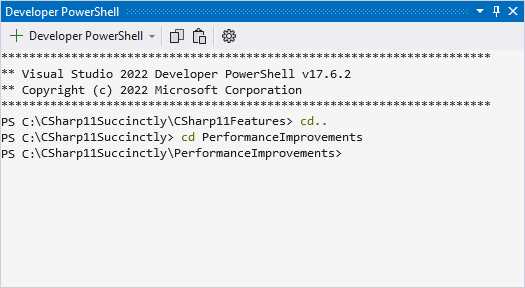

Next, you need to open up the Terminal window in Visual Studio. You can do this by clicking View > Terminal in the Visual Studio menu, or you can hold down Ctrl + ` to open up the Developer PowerShell.

Note: The menu says Terminal, but the opened window title says Developer PowerShell.

We will run the benchmarking project from the command line, so having the Terminal window open will make it easier.

Figure 41: Developer PowerShell in Visual Studio

With this window open, change the directory to the benchmarking project. In my example, you can find the code in a project called PerformanceImprovements in the main solution. We are ready to write some code. Let’s get started.

LINQ—improvements to existing operations

By now, most developers are familiar with LINQ. It allows us to express complicated operations concisely using the LINQ syntax. This expressivity does come with a bit of an overhead cost. This overhead cost leads some developers to avoid using LINQ in their code, but LINQ has its place and is extremely useful as long as you are cognizant of where you use it in your code.

With .NET 7, these improvements to performance come to LINQ out of the box. It means that merely upgrading your solution from .NET 6 to .NET 7 gives it a performance boost without you having to write a single line of optimization code.

Code Listing 65: LINQ Example on Existing Operations

using BenchmarkDotNet.Attributes; using BenchmarkDotNet.Running; namespace PerformanceImprovements; public class Program { static void Main(string[] args) => BenchmarkRunner.Run<Bench>(); } [MemoryDiagnoser(displayGenColumns: false)] [DisassemblyDiagnoser] [HideColumns("Error", "StdDev", "Median", "RatioSD")] public class Bench { private IEnumerable<float> _randFloats = CreateRandomFloats(); [Benchmark] public float Min() => _randFloats.Min(); [Benchmark] public float Max() => _randFloats.Max(); [Benchmark] public float Average() => _randFloats.Average(); [Benchmark] public float Sum() => _randFloats.Sum(); private static float[] CreateRandomFloats() { var r = new Random(45); var results = new float[100_000]; for (int i = 0; i < results.Length; i++) { results[i] = (float)r.NextDouble(); } return results; } } |

Consider the code in Code Listing 65 that creates a collection of 100,000 random floating-point numbers and then performs calculations on that collection via the LINQ extension methods Min, Max, Average, and Sum.

In the Terminal window, run the command dotnet run -c Release -f net6.0 --filter '**' --runtimes net6.0 to build the benchmarks in the release configuration targeting .NET 6 and run the project on .NET 6. The benchmarking might take a few minutes, and you see a summary of the result when it completes (Code Listing 66).

Code Listing 66: Benchmark Results for .NET 6

[Host] : .NET 6.0.16 (6.0.1623.17311), X64 RyuJIT AVX2 DefaultJob : .NET 6.0.16 (6.0.1623.17311), X64 RyuJIT AVX2 | Method | Mean | Code Size | Allocated | |-------- |---------:|----------:|----------:| | Min | 636.9 us | 347 B | 33 B | | Max | 592.4 us | 411 B | 33 B | | Average | 541.8 us | 343 B | 33 B | | Sum | 550.9 us | 258 B | 33 B | |

Next, run the command dotnet run -c Release -f net7.0 --filter '**' --runtimes net7.0 to build the benchmarks in the release configuration targeting .NET 7 and run the project on .NET 7. When it completes, you see a similar summary (Code Listing 67), only this time, using .NET 7, the results are very different.

Code Listing 67: Benchmark Results for .NET 7

[Host] : .NET 7.0.5 (7.0.523.17405), X64 RyuJIT AVX2 DefaultJob : .NET 7.0.5 (7.0.523.17405), X64 RyuJIT AVX2 | Method | Mean | Code Size | Allocated | |-------- |---------:|----------:|----------:| | Min | 101.1 us | 518 B | - | | Max | 122.5 us | 629 B | - | | Average | 200.7 us | 627 B | - | | Sum | 191.6 us | 420 B | - | |

To make sense of the results, we must first define what we see here. The following is true:

· Mean: Arithmetic mean of all the measurements

· Allocated: Allocated memory per single operation (managed only, inclusive, 1KB = 1024B)

· 1 ns: 1 Nanosecond

· 1 us: 1 Microsecond

Comparing the results from .NET 6 with those of .NET 7, we can see that the mean times reduce significantly when using .NET 7, and using .NET 7 also does not create any allocations.

While the improvements in the previous example are introduced in existing operations, performance improvements can result in using new APIs in place of the previous ones. Let us look at the popular OrderBY LINQ method next.

LINQ—using the new Order method

The OrderBy method in LINQ enables the creation of a sorted copy of the input enumerable. Code Listing 68 lists the benchmarking code required for the next example.

Code Listing 68: LINQ Example Using the New Order() Method

using BenchmarkDotNet.Attributes; using BenchmarkDotNet.Running; namespace PerformanceImprovements; public class Program { static void Main(string[] args) => BenchmarkRunner.Run<Bench>(); } [MemoryDiagnoser(displayGenColumns: false)] [DisassemblyDiagnoser] [HideColumns("Error", "StdDev", "Median", "RatioSD")] public class Bench { [Params(1024)] public int Length { get; set; } private int[] _intArray; [GlobalSetup] public void Setup() => _intArray = Enumerable.Range(1, Length).Reverse().ToArray(); [Benchmark(Baseline = true)] public void OrderBy() { foreach (int _ in _intArray.OrderBy(x => x)) { } } [Benchmark] public void Order() { foreach (int _ in _intArray.Order()) { } } } |

You can see that I have an array of integers that I sort using OrderBy(x => x) and another new Order() method available in .NET 7. Incidentally, .NET 7 also introduces OrderDescending().

If you try and run this benchmark code using dotnet run -c Release -f net6.0 --filter '**' --runtimes net6.0, you receive a build error. You see this error because the Order() method is unavailable in .NET 6.

With that in mind, run the Console application using .NET 7 by changing the command to dotnet run -c Release -f net7.0 --filter '**' --runtimes net7.0.

Code Listing 69: OrderBy() Versus Order() Results

| Method | Length | Mean | Ratio | Code Size | Allocated | Alloc Ratio | |-------- |------- |---------:|------:|----------:|----------:|------------:| | OrderBy | 1024 | 95.13 us | 1.00 | 427 B | 12.3 KB | 1.00 | | Order | 1024 | 90.64 us | 0.96 | 336 B | 8.28 KB | 0.67 | |

The results in Code Listing 69 speak for themselves. With OrderBy(), the caller passes a Func<TSource, TKey> predicate, which is used to extract a comparison key for each item. Seeing as it is pretty common to sort items with themselves as the keys, .NET 7 performs the same sorting operation with an implicit x => x done on behalf of the caller.

If you face a situation where you need to use OrderBy(x => x), consider using the Order() method instead. As you can see from Code Listing 69, the allocations are reduced significantly in .NET 7 using the new Order() method.

JSON improvements

.NET Core 3.0 introduced developers to System.Text.Json with a significant investment going into .NET 7. One of the pitfalls, though, concerns how the library caches data. To improve serialization and deserialization performance when the source generator isn’t used, reflection is used by System.Text.Json to emit custom code for reading and writing members of the processed types.

The library incurs a more significant one-time cost performing this code generation, making subsequent handling of the types fast (assuming that the generated code is available for use). The generated handlers require them to be stored somewhere, which is where JsonSerialierOptions come into play.

The idea behind JsonSerializerOptions is that developers would create an instance once and pass that around to all the required serialization and deserialization calls. If, however, developers deviate from the recommended model, performance tanks. What happens now is that instead of taking the hit for the reflection invoke costs, every new instance of JsonSerializerOptions results in a regeneration of the handlers via reflection emit, which in turn increases the cost of the serialization and deserialization.

Consider the code illustrated in Code Listing 70.

Code Listing 70: JSON Serialization

using System.Text.Json; using BenchmarkDotNet.Attributes; using BenchmarkDotNet.Running; namespace PerformanceImprovements; public class Program { static void Main(string[] args) => BenchmarkRunner.Run<Bench>(); } [MemoryDiagnoser(displayGenColumns: false)] [DisassemblyDiagnoser] [HideColumns("Error", "StdDev", "Median", "RatioSD")] public class Bench { private JsonSerializerOptions _options = new JsonSerializerOptions(); private StudentPoco _student = new StudentPoco(); [Benchmark(Baseline = true)] public string ImplicitOptions() => JsonSerializer.Serialize(_student); [Benchmark] public string WithCached() => JsonSerializer.Serialize(_student, _options); [Benchmark] public string WithoutCached() => JsonSerializer.Serialize(_student, new JsonSerializerOptions()); } public class StudentPoco { public int Id { get; set; } public string Name { get; set; } public int Age { get; set; } } |

Running the benchmarks using .NET 6 produces the results in Code Listing 71.

Code Listing 71: JSON Serialization with .NET 6

[Host] : .NET 6.0.16 (6.0.1623.17311), X64 RyuJIT AVX2 DefaultJob : .NET 6.0.16 (6.0.1623.17311), X64 RyuJIT AVX2 | Method | Mean | Code Size | Allocated | Alloc Ratio | |---------------- |-------------:|----------:|----------:|------------:| | ImplicitOptions | 325.3 ns | 999 B | 232 B | 1.00 | | WithCached | 313.1 ns | 871 B | 232 B | 1.00 | | WithoutCached | 344,578.1 ns | 1,180 B | 13623 B | 58.72 | |

Running the benchmarks using .NET 7, illustrated in Code Listing 72, paints a very different picture.

Code Listing 72: JSON Serialization with .NET 7

[Host] : .NET 7.0.5 (7.0.523.17405), X64 RyuJIT AVX2 DefaultJob : .NET 7.0.5 (7.0.523.17405), X64 RyuJIT AVX2 | Method | Mean | Code Size | Allocated | Alloc Ratio | |---------------- |-----------:|----------:|----------:|------------:| | ImplicitOptions | 323.4 ns | 1,004 B | 80 B | 1.00 | | WithCached | 327.7 ns | 680 B | 80 B | 1.00 | | WithoutCached | 1,112.5 ns | 865 B | 311 B | 3.89 | |

.NET 7 adds a global cache containing the type information and separates it from the options instances. Using JsonSerializerOptions still does cache, but if new handlers are generated with reflection emit, those are cached at the global level.

As seen in the results for WithoutCached(), creating a new JsonSerializerOptions is still expensive, but much less expensive when using .NET 7.

In conclusion

Illustrating all the performance improvements made in .NET 7 would take a whole book on its own. The takeaway here is to realize that even though .NET 7 is a Standard Term Support release, that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t upgrade your projects to .NET 7. The performance boost that your projects gain out of the box is reason enough to upgrade to .NET 7.

For more information on BenchmarkDotNet, refer to their documentation here.

- 1800+ high-performance UI components.

- Includes popular controls such as Grid, Chart, Scheduler, and more.

- 24x5 unlimited support by developers.